Temozolomide, sold under the brand name Temodar among others, is an anticancer medication used to treat brain tumors such as glioblastoma and anaplastic astrocytoma.[4][5] It is taken by mouth or via intravenous infusion.[4][5]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Temodar, Temodal, Temcad, others[1] |

| Other names | TMZ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601250 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | almost 100% |

| Protein binding | 15% (10–20%) |

| Metabolism | hydrolysis |

| Metabolites | 3-methyl-(triazen-1-yl)imidazole-4-carboxamide (MTIC, the active species); temozolomide acid |

| Elimination half-life | 1.8 hours |

| Excretion | mainly kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.158.652 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

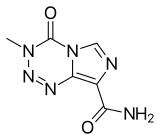

| Formula | C6H6N6O2 |

| Molar mass | 194.154 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 212 °C (414 °F) (decomp.) |

| |

| |

| | |

The most common side effects with temozolomide are nausea, vomiting, constipation, loss of appetite, alopecia (hair loss), headache, fatigue, convulsions (seizures), rash, neutropenia or lymphopenia (low white-blood-cell counts), and thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet counts).[5] People receiving the solution for infusion may also have injection-site reactions, such as pain, irritation, itching, warmth, swelling and redness, as well as bruising.[5]

Temozolomide is an alkylating agent used to treat serious brain cancers; most commonly as second-line treatments for astrocytoma and as the first-line treatment for glioblastoma.[4][6][7] Olaparib in combination with temozolomide demonstrated substantial clinical activity in relapsed small cell lung cancer.[8] It is available as a generic medication.

Medical uses

editIn the United States, temozolomide is indicated for the treatment of adults with newly diagnosed glioblastoma concomitantly with radiotherapy and subsequently as monotherapy treatment;[4][9] or adults with newly diagnosed or refractory anaplastic astrocytoma.[4][9]

In the European Union, temozolomide is indicated for adults with newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme concomitantly with radiotherapy and subsequently as monotherapy treatment;[5][6] or children from the age of three years, adolescents and adults with malignant glioma, such as glioblastoma multiforme or anaplastic astrocytoma, showing recurrence or progression after standard therapy.[5][6]

Temozolomide is also used to treat aggressive pituitary tumors and pituitary cancer.[10]

Contraindications

editTemozolomide is contraindicated in people with hypersensitivity to it or to the similar drug dacarbazine.[11]

Adverse effects

editThe most common side effects include nausea (feeling sick), vomiting, constipation, loss of appetite, alopecia (hair loss), headache, fatigue (tiredness), convulsions (fits), rash, neutropenia or lymphopenia (low white-blood-cell counts), and thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet counts).[5] People receiving the solution for infusion may also have injection-site reactions, such as pain, irritation, itching, warmth, swelling and redness, as well as bruising.[5]

Interactions

editCombining temozolomide with other myelosuppressants may increase the risk of myelosuppression.[11]

Pharmacology

editMechanism of action

editThe therapeutic benefit of temozolomide depends on its ability to alkylate/methylate DNA, which most often occurs at the N-7 or O-6 positions of guanine residues.[12][medical citation needed] This methylation damages the DNA and triggers the death of tumor cells.[13][medical citation needed] However, some tumor cells are able to repair this type of DNA damage, and therefore diminish the therapeutic efficacy of temozolomide, by expressing a protein O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase (AGT) encoded in humans by the O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene.[14] In some tumors, epigenetic silencing of the MGMT gene prevents the synthesis of this enzyme, and as a consequence such tumors are more sensitive to killing by temozolomide.[15] Conversely, the presence of AGT protein in brain tumors predicts poor response to temozolomide and these patients receive little benefit from chemotherapy with temozolomide.[16]

Pharmacokinetics

editTemozolomide is quickly and almost completely absorbed from the gut, and readily penetrates the blood–brain barrier; the concentration in the cerebrospinal fluid is 30% of the concentration in the blood plasma.[medical citation needed] Intake with food decreases maximal plasma concentrations by 33% and the area under the curve by 9%.[medical citation needed] Only 15% (10–20%) of the substance are bound to blood plasma proteins.[medical citation needed] Temozolomide is a prodrug; it is spontaneously hydrolyzed at physiological pH to 3-methyl-(triazen-1-yl)imidazole-4-carboxamide (MTIC), which further splits into monomethylhydrazine, likely the active methylating agent, and 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide (AIC).[medical citation needed] Other metabolites include temozolomide acid and unidentified hydrophilic substances.[11]

Plasma half-life is 1.8 hours.[medical citation needed] The substance and its metabolites are mainly excreted via the urine.[11]

-

MTIC, the active metabolite

-

AIC (part of the naturally occurring AICA ribonucleotide)

-

The related drug dacarbazine[17] for comparison

Chemical properties

editTemozolomide is an imidazotetrazine derivative.[17] It is slightly soluble in water and aqueous acids,[18] and decomposes at 212 °C (414 °F).[19] It was recently discovered that temozolomide is an explosive, tentatively assigned as UN Class 1.[20][21]

Temozolomide has also been reported to be a comparatively safe and stable in situ source of diazomethane in organic synthesis.[citation needed] In particular, use as a methylating and cyclopropanating reagent has been demonstrated.[22]

History

editThe agent was discovered at Aston University in Birmingham, England. Its preclinical activity was reported in 1987.[17][23][24]

It was approved for medical use in the European Union in January 1999,[5] and in the United States in August 1999.[25] The intravenous formulation was approved in the United States in February 2009.[26]

Research

editLaboratory studies and clinical trials have started investigating the possibility of increasing the anticancer potency of temozolomide by combining it with other pharmacologic agents. For example, clinical trials have indicated that the addition of chloroquine might be beneficial for the treatment of glioma patients.[27] Laboratory studies found that temozolomide killed brain tumor cells more efficiently when epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), a component of green tea, was added; however, the efficacy of this effect has not yet been confirmed in brain-tumor patients.[28] Preclinical studies reported in 2010 on investigations into the use of the novel oxygen diffusion-enhancing compound trans sodium crocetinate (TSC) when combined with temozolomide and radiation therapy[29] and a clinical trial was underway as of August 2015[update].[30]

While the above-mentioned approaches have investigated whether the combination of temozolomide with other agents might improve therapeutic outcome, efforts have also started to study whether altering the temozolomide molecule itself can increase its activity. One such approach permanently fused perillyl alcohol, a natural compound with demonstrated therapeutic activity in brain cancer patients,[31] to the temozolomide molecule. The resultant novel compound, called NEO212 or TMZ-POH, revealed anticancer activity that was significantly greater than that of either of its two parent molecules, temozolomide and perillyl alcohol. Although as of 2016[update], NEO212 has not been tested in humans, it has shown superior cancer therapeutic activity in animal models of glioma,[32] melanoma,[33] and brain metastasis of triple-negative breast cancer.[34]

Because tumor cells that express the O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) gene are more resistant to the effects of temozolomide, researchers investigated whether the inclusion of O6-benzylguanine (O6-BG), an AGT inhibitor, could overcome this resistance and improve the drug's therapeutic effectiveness. In the laboratory, this combination indeed showed increased temozolomide activity in tumor-cell culture in vitro and in animal models in vivo.[35] However, a recently[timeframe?] completed phase-II clinical trial with brain-tumor patients yielded mixed outcomes; while there was some improved therapeutic activity when O6-BG and temozolomide were given to patients with temozolomide-resistant anaplastic glioma, there seemed to be no significant restoration of temozolomide sensitivity in patients with temozolomide-resistant glioblastoma multiforme.[36]

Some efforts focus on engineering hematopoietic stem cells expressing the MGMT gene prior to transplanting them into brain-tumor patients. This would allow for the patients to receive stronger doses of temozolomide, since the patient's hematopoietic cells would be resistant to the drug.[37]

High doses of temozolomide in high-grade gliomas have low toxicity, but the results are comparable to the standard doses.[38]

Two mechanisms of resistance to temozolomide effects have now been described: 1) intrinsic resistance conferred by MGMT deficiency (MGMTd) and 2) intrinsic or acquired resistance through MMR deficiency (MMRd). The MGMT enzyme is the first line of repair of mismatched bases created by temozolomide. Cells are normally MGMT proficient (MGMTp) as they have an unmethylated MGMT promoter allowing the gene to be expressed normally. In this state, temozolomide induced DNA damage is able to be efficiently repaired in tumor cells (and normal cells) by the active MGMT enzyme. Cells may grow and pass through the cell cycle normally without arrest or death. However, some tumors cells are MGMT deficient (MGMTd). This is most commonly due to abnormal methylation of the MGMT gene promoter and suppression of gene expression. MGMTd has also been described to occur by promoter rearrangement. In cells with MGMTd, DNA damage by temozolomide activates the next stage of repair in cells with a proficient Mismatch Repair enzyme complex (MMRp). In MMRp the MMR protein complex identifies the damage and causes cells to arrest and undergo death which inhibits tumor growth. However, if cells have combined MGMTd and MMR deficiency (MGMTd + MMRd) then cells retain the induced mutations and continue to cycle and are resistant to effects of temozolomide.[medical citation needed]

In gliomas and other cancers MMRd has now been reported to occur as primary MMRd (intrinsic or germline Lynch bMMRd) or as secondary MMRd (acquired - not present in the original untreated tumor). The latter occurs after effective treatment and cytoreduction of tumors with temozolomide and then selection or induction of mutant MSH6, MSH2, MLH1, or PMS2 proteins and cells which are MMRd and temozolomide resistant. The latter is described as an acquired resistance pathway with hotspot mutations in glioma patients (MSH6 p.T1219I).[39]

References

edit- ^ "Temozolomide". Drugs.com. 4 May 2020. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Temodal Capsules - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 24 October 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "Temodar- temozolomide capsule Temodar- temozolomide injection, powder, lyophilized, for solution". DailyMed. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Temodal EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ a b c "Guidance on the use of temozolomide for the treatment of recurrent malignant glioma (brain cancer)" (PDF). 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Sasmita AO, Wong YP, Ling AP (February 2018). "Biomarkers and therapeutic advances in glioblastoma multiforme". Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 14 (1): 40–51. doi:10.1111/ajco.12756. PMID 28840962.

- ^ Farago AF, Yeap BY, Stanzione M, Hung YP, Heist RS, Marcoux JP, et al. (October 2019). "Combination Olaparib and Temozolomide in Relapsed Small-Cell Lung Cancer". Cancer Discovery. 9 (10): 1372–1387. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0582. PMC 7319046. PMID 31416802.

- ^ a b "FDA approves new and updated indications for temozolomide under Projec". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 September 2023. Archived from the original on 15 September 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Raverot G, Burman P, McCormack A, Heaney A, Petersenn S, Popovic V, et al. (January 2018). "European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of aggressive pituitary tumours and carcinomas". European Journal of Endocrinology. 178 (1): G1–G24. doi:10.1530/EJE-17-0796. PMID 29046323.

- ^ a b c d Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. 2018. Temodal 5 mg-Hartkapseln.

- ^ Fu D, Calvo JA, Samson LD (January 2012). "Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents". Nature Reviews. Cancer. 12 (2): 104–120. doi:10.1038/nrc3185. PMC 3586545. PMID 22237395.

- ^ Li Z, Pearlman AH, Hsieh P (February 2016). "DNA mismatch repair and the DNA damage response". DNA Repair. 38: 94–101. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2015.11.019. PMC 4740233. PMID 26704428.

- ^ Jacinto FV, Esteller M (August 2007). "MGMT hypermethylation: a prognostic foe, a predictive friend". DNA Repair. 6 (8): 1155–1160. doi:10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.03.013. PMID 17482895.

- ^ Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF, de Tribolet N, Weller M, et al. (March 2005). "MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (10): 997–1003. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa043331. PMID 15758010. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ Stupp R, Hegi ME, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Taphoorn MJ, Janzer RC, et al. (May 2009). "Effects of radiotherapy with concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide versus radiotherapy alone on survival in glioblastoma in a randomised phase III study: 5-year analysis of the EORTC-NCIC trial". The Lancet. Oncology. 10 (5): 459–466. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70025-7. PMID 19269895. S2CID 25150249.

- ^ a b c Sansom C (July 2009). "Temozolomide – birth of a blockbuster" (PDF). Chemistry World: 48–51. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ^ "Temodal: EPAR – Scientific Discussion" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 13 December 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Dinnendahl, V, Fricke, U, eds. (2016). Arzneistoff-Profile (in German). Vol. 9 (29 ed.). Eschborn, Germany: Govi Pharmazeutischer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7741-9846-3.

- ^ Sperry JB, Stone S, Azuma M, Barrett C (2021). "Importance of Thermal Stability Data to Avoid Dangerous Reagents: Temozolomide Case Study". Organic Process Research & Development. 25 (7): 1690–1700. doi:10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00206. S2CID 237644612.

- ^ Lowe D (12 July 2021). "Temozolomide Is Explosive". Science (Blog). Archived from the original on 4 June 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Svec RL, Hergenrother PJ (January 2020). "Imidazotetrazines as Weighable Diazomethane Surrogates for Esterifications and Cyclopropanations". Angewandte Chemie. 59 (5): 1857–1862. doi:10.1002/anie.201911896. PMC 6982548. PMID 31793158.

- ^ "Malcolm Steven – interview". Cancer Research UK impact & achievements page. 22 August 2013. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012.

- ^ Newlands ES, Stevens MF, Wedge SR, Wheelhouse RT, Brock C (January 1997). "Temozolomide: a review of its discovery, chemical properties, pre-clinical development and clinical trials". Cancer Treatment Reviews. 23 (1): 35–61. doi:10.1016/S0305-7372(97)90019-0. PMID 9189180.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Temodar (Temozolomide) NDA# 021029". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 30 March 2001. Archived from the original on 31 March 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Temodar NDA #022277". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Gilbert MR (March 2006). "New treatments for malignant gliomas: careful evaluation and cautious optimism required". Annals of Internal Medicine. 144 (5): 371–373. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00015. PMID 16520480. S2CID 21181702.

- ^ Pyrko P, Schönthal AH, Hofman FM, Chen TC, Lee AS (October 2007). "The unfolded protein response regulator GRP78/BiP as a novel target for increasing chemosensitivity in malignant gliomas". Cancer Research. 67 (20): 9809–9816. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0625. PMID 17942911.

- ^ Sheehan J, Cifarelli CP, Dassoulas K, Olson C, Rainey J, Han S (August 2010). "Trans-sodium crocetinate enhancing survival and glioma response on magnetic resonance imaging to radiation and temozolomide". Journal of Neurosurgery. 113 (2): 234–239. doi:10.3171/2009.11.JNS091314. PMID 20001586.

- ^ "Safety and Efficacy Study of Trans Sodium Crocetinate (TSC) With Concomitant Radiation Therapy and Temozolomide in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma (GBM)". ClinicalTrials.gov. November 2011. Archived from the original on 21 October 2014. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ Da Fonseca CO, Teixeira RM, Silva JC, Fischer JD, Meirelles OC, Landeiro JA, et al. (December 2013). "Long-term outcome in patients with recurrent malignant glioma treated with Perillyl alcohol inhalation". Anticancer Research. 33 (12): 5625–5631. PMID 24324108.

- ^ Cho HY, Wang W, Jhaveri N, Lee DJ, Sharma N, Dubeau L, et al. (August 2014). "NEO212, temozolomide conjugated to perillyl alcohol, is a novel drug for effective treatment of a broad range of temozolomide-resistant gliomas". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 13 (8): 2004–2017. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-13-0964. PMID 24994771.

- ^ Chen TC, Cho HY, Wang W, Nguyen J, Jhaveri N, Rosenstein-Sisson R, et al. (March 2015). "A novel temozolomide analog, NEO212, with enhanced activity against MGMT-positive melanoma in vitro and in vivo". Cancer Letters. 358 (2): 144–151. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.12.021. PMID 25524552.

- ^ Chen TC, Cho HY, Wang W, Barath M, Sharma N, Hofman FM, et al. (May 2014). "A novel temozolomide-perillyl alcohol conjugate exhibits superior activity against breast cancer cells in vitro and intracranial triple-negative tumor growth in vivo". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 13 (5): 1181–1193. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-13-0882. PMID 24623736.

- ^ Ueno T, Ko SH, Grubbs E, Yoshimoto Y, Augustine C, Abdel-Wahab Z, et al. (March 2006). "Modulation of chemotherapy resistance in regional therapy: a novel therapeutic approach to advanced extremity melanoma using intra-arterial temozolomide in combination with systemic O6-benzylguanine". Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 5 (3): 732–738. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0098. PMID 16546988. S2CID 14455128.

- ^ Quinn JA, Jiang SX, Reardon DA, Desjardins A, Vredenburgh JJ, Rich JN, et al. (March 2009). "Phase II trial of temozolomide plus o6-benzylguanine in adults with recurrent, temozolomide-resistant malignant glioma". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 27 (8): 1262–1267. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.8417. PMC 2667825. PMID 19204199.

- ^ "Investigative Engineered Bone Marrow Cell Therapy". Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Dall'oglio S, D'Amico A, Pioli F, Gabbani M, Pasini F, Passarin MG, et al. (December 2008). "Dose-intensity temozolomide after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in operated high-grade gliomas". Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 90 (3): 315–319. doi:10.1007/s11060-008-9663-9. PMID 18688571. S2CID 21517366.

- ^ Touat M, Li YY, Boynton AN, Spurr LF, Iorgulescu JB, Bohrson CL, et al. (April 2020). "Mechanisms and therapeutic implications of hypermutation in gliomas". Nature. 580 (7804): 517–523. Bibcode:2020Natur.580..517T. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2209-9. PMC 8235024. PMID 32322066.

Further reading

edit- Kaloshi G, Benouaich-Amiel A, Diakite F, Taillibert S, Lejeune J, Laigle-Donadey F, et al. (May 2007). "Temozolomide for low-grade gliomas: predictive impact of 1p/19q loss on response and outcome". Neurology. 68 (21): 1831–1836. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000262034.26310.a2. PMID 17515545.

External links

edit- "Temozolomide (Temodal)". Cancer Research UK.

- "Temozolomide". NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms. National Cancer Institute.

- "Temozolomide". National Cancer Institute. 5 October 2006.