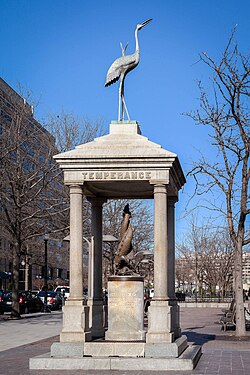

Temperance Fountain (Washington, D.C.)

The Temperance Fountain is a fountain and statue located in Washington, D.C., donated to the city in 1882 by Henry D. Cogswell, a dentist from San Francisco, California, who was a crusader in the temperance movement.[2] This fountain was one of a series of temperance fountains he designed and commissioned in a belief that easy access to cool drinking water would keep people from consuming alcoholic beverages.[3]

Temperance Fountain | |

| |

| Location | 7th Street & Indiana Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′37.6″N 77°1′18″W / 38.893778°N 77.02167°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1884 |

| Architect | Henry D. Cogswell |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian |

| MPS | Memorials in Washington, D.C. |

| NRHP reference No. | 07001061[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 12, 2007 |

Design

editThe fountain has four stone columns supporting a canopy on whose sides the words "Faith," "Hope," "Charity," and "Temperance" are chiseled. Atop this canopy is a life-sized heron, and the centerpiece is a pair of entwined heraldic scaly dolphins. Originally, visitors were supposed to freely drink ice water flowing from the dolphins' snouts with a brass cup attached to the fountain and the overflow was collected by a trough for horses,[4] but the city tired of having to replenish the ice in a reservoir underneath the base and disconnected the supply pipes.[5]

The inscription reads:

(Base of fish:)

PRESENTED BY

DR. HENRY D. COGSWELL

OF SAN FRANCISCO CAL

(Top of temple:)

TEMPERANCE

FAITH

HOPE

CHARITY

-

Inscription

-

Sculpture of two dolphins inside the enclosure

-

Great Blue Heron atop the fountain

Location

editThe Temperance Fountain was originally placed at a prominent location: Seventh and Pennsylvania Avenue, across from Center Market and near to "Hooker's Division" (now the Federal Triangle). The message was to drink water, not whiskey, as there were so many saloons along the Avenue to tempt passersby. This was near the halfway point between the Capitol and White House. For many years after National Prohibition, it ironically sat in front of the Apex Liquor Store, which operated in the ground floor of the Central National Bank Building.[6]

In 1987, it was relocated about 100 feet north during the renewal by the Pennsylvania Avenue Development Corporation, since the statue was regarded as undesirable from the start.[7] The PADC created Indiana Plaza, and the Temperance Fountain swapped locations with the monument to the Grand Army of the Republic, which was considered historically more significant.

Today the fountain sits at the corner of Seventh Street and Indiana Avenue, NW, across from the National Archives and Navy Memorial, where thousands of tourists and workers walk past daily without noticing it. The Temperance Fountain has been called "the city's ugliest statue".[8] NBC correspondent Bryson Rash, writing in Footnote Washington, a 1981 book of capital lore, reported that "these unusual and awkward structures spurred the movement across the country for city fine arts commissions to screen such gifts" prior to funding.[9] In April 1945, Sen. Sheridan Downey of California introduced a Senate resolution to remove the fountain, but, preoccupied with World War II, Congress ignored the resolution and it died in committee.[5]

Upkeep

editThe fountain is also the source of the name for the Cogswell Society, a small group of Washington professionals who have taken it upon themselves to take care of the fountain.[10] In 1984, it was placed on the Downtown Historic District National Register #84003901.

Other Cogswell fountains

editCogswell's fountains can be found in Washington, D.C., Tompkins Square Park New York City,[3] Washington Square, San Francisco[11][12] and Rockville, Connecticut.[13][14][15] Other examples were erected and then torn down at: Buffalo, Rochester, Boston Common,[16][17] Fall River, Massachusetts, Pacific Grove, California,[18][19] and San Francisco (California and Market Streets).[20]

See also

editReferences

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| NCPC Cinema Visiting Washington's Lesser Known Memorials[21] |

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Temperance Fountain, (sculpture)". Inventories of American Painting and Sculpture, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ a b "Tompkins Square Park". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ Goode, James M. The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1974, ISBN 0-87474-138-6, p. 358

- ^ a b Kitsock, Greg (January 3, 1992). "Fountain of Hooch". Washington City Paper. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Peck, Garrett (2011). Prohibition in Washington, D.C.: How Dry We Weren't. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-1-60949-236-6.

- ^ "Cogswell Fountain" (scroll down to section originally taken from http://dynaweb.oac.cdlib.org/sgml/chs/ms_0690.sgm, which no longer exists). Retrieved 2008-10-13.

{{cite web}}: External link in|format= - ^ "...Toasted Temperance". Washington Post. September 21, 2003. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ Knutson, Lawrence (March 4, 2002). "Political quirks and curiosities". Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- ^ Kitsock, Greg (March 6, 1992). "All's Well That Ends With a Drink to Cogswell". Washington City Paper. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ CA000016 OR CA000029 – Smithsonian Institution Research Information System

- ^ "FRANKLIN, Benjamin statue in Washington Square in San Francisco, California". Archived from the original on 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

- ^ Monica Polanco (August 4, 2005). "Dr. Cogswell Returns To Central Park". The Hartford Courant.

- ^ "Cogswell Fountain". Archived from the original on 2010-12-15. Retrieved 2011-08-05.

- ^ Jason Rowe (2006-05-19). "Cogswell Fountain restoration earns RDA an award". Smartgrowthforvernon.org. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ^ Jane Holtz Kay (2006). Lost Boston. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 254. ISBN 978-1-55849-527-2.

cogswell fountain boston.

- ^ American architect and architecture. Vol. 41. 1893. p. 918.

- ^ Kent Seavey (2005). Pacific Grove. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2964-6.

- ^ "Pacific Grove: The Chautauqua Years / Birdseye View of Pacific Grove". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Image Breakers: Dr. Cogswell's Stature Overturned Under Shadow of Night By a Silent Gang of Hoodlum Miscreants". San Francisco Call. 3 January 1894. p. 8.

- ^ "Visiting Washington's Lesser Known Memorials". National Capital Planning Commission. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

External links

edit- "Cogswell Temperance Fountain", wikimapia

- dcMemorials Archived 2010-12-16 at the Wayback Machine, photos and further information on the Temperance Fountain

- Temperance Tour, a tour of Prohibition-related sites in Washington, D.C., including the Temperance Fountain

- Kitsock, Greg (March 6, 1992). "All's well that ends with a drink to Cogswell". Washington City Paper. Retrieved September 4, 2016.