| This is the template test cases page for the sandbox of Template:Sfnp. to update the examples. If there are many examples of a complicated template, later ones may break due to limits in MediaWiki; see the HTML comment "NewPP limit report" in the rendered page. You can also use Special:ExpandTemplates to examine the results of template uses. You can test how this page looks in the different skins and parsers with these links: |

| This is an end-to-end test of Template:Sfnp/sandbox and Module:Footnotes/sandbox. There should be no Lua errors, and when you "view source", the strings "no target" or "multiple targets" should not appear, except for this box. |

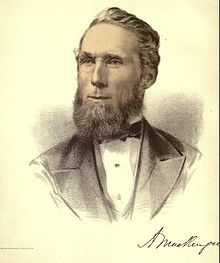

Alexander Mackenzie | |

|---|---|

Mackenzie in 1878 | |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Canada | |

| In office November 7, 1873 – October 8, 1878 | |

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Governor General | The Earl of Dufferin |

| Preceded by | John A. Macdonald |

| Succeeded by | John A. Macdonald |

| Leader of the Liberal Party | |

| In office March 6, 1873 – May 4, 1880 | |

| Preceded by | Edward Blake |

| Succeeded by | Edward Blake |

| Member of the House of Commons of Canada | |

| In office September 20, 1867 – April 17, 1892 | |

| More... | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 28, 1822 Logierait, Scotland |

| Died | April 17, 1892 (aged 70) Toronto, Ontario, Canada |

| Resting place | Lakeview Cemetery, Sarnia, Ontario |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 3 |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Canada |

| Branch/service | Canadian militia |

| Years of service | 1866–1874 |

| Rank | Major |

| Unit | 27th (Lambton) Battalion of Infantry |

| Battles/wars | Fenian Raids |

Alexander Mackenzie (January 28, 1822 – April 17, 1892) was a Canadian politician who served as the second prime minister of Canada, in office from 1873 to 1878.

Mackenzie was born in Logierait, Perthshire, Scotland. He left school at the age of 13, following his father's death, to help his widowed mother, and trained as a stonemason. Mackenzie immigrated to the Province of Canada when he was 19, settling in what became Ontario. His masonry business prospered, allowing him to pursue other interests – such as the editorship of a pro-Reformist newspaper called the Lambton Shield.[2] Mackenzie was elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada in 1862, as a supporter of George Brown.

In 1867, Mackenzie was elected to the new House of Commons of Canada for the Liberal Party. He became leader of the party (thus Leader of the Opposition) in mid-1873, and a few months later succeeded John A. Macdonald as prime minister, following Macdonald's resignation in the aftermath of the Pacific Scandal. Mackenzie and the Liberals won a clear majority at the 1874 election. He was popular among the general public for his humble background and consistent democratic principles.

A prime minister, Mackenzie continued the nation-building programme that had been begun by his predecessor. His government established the Supreme Court of Canada and Royal Military College of Canada, and created the District of Keewatin to better administer Canada's newly acquired western territories. However, it made little progress on the transcontinental railway, and struggled to deal with the aftermath of the Panic of 1873. At the 1878 election, Mackenzie's government suffered a landslide defeat. He remained leader of the Liberal Party for another two years, and continued on as a Member of Parliament (MP) until his death, due to a stroke.[3][4][5]

Early life

editMackenzie was born on January 28, 1822, in Logierait, Perthshire, Scotland, the son of Mary Stewart (Fleming) and Alexander Mackenzie Sr. (born 1784) who were married in 1817.[2] The site of his birthplace is known as Clais-'n-deoir (the Hollow of the Weeping), where families said their goodbyes as the convicted were led to nearby Gallows Hill. The house in which he was born was built by his father. He was the third of 10 boys, seven of whom survived infancy.[2] Alexander Mackenzie Sr. was a carpenter and ship's joiner who had to move around frequently for work after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. Mackenzie's father died on March 7, 1836, and at the age of 13, Alexander Mackenzie Jr. was thus forced to end his formal education to help support his family. He apprenticed as a stonemason and met his future wife, Helen Neil, in Irvine, where her father was also a stonemason.[2] The Neils were Baptist and shortly thereafter, Mackenzie converted from Presbyterianism to Baptist beliefs.[2] Together with the Neils, he immigrated to Canada in 1842 to seek a better life. Mackenzie's faith was to link him to the increasingly influential temperance cause, particularly strong in Canada West (Ontario) where he lived, a constituency of which he later represented in the House of Commons.[2]

The Neils and Mackenzie settled in Kingston, Ontario. The limestone in the area proved too hard for his stonemason tools, and not having money to buy new tools, Mackenzie took a job as a labourer constructing a building on Princess Street.[2] The contractor on the job claimed financial difficulty, so Mackenzie accepted a promissory note for summer wages. The note later proved to be worthless. Subsequently, Mackenzie won a contract building a bomb-proof arch at Fort Henry. He later became a foreman on the construction of Kingston's four Martello Towers – Murney Tower, Fort Frederick, Cathcart Tower, and Shoal Tower. He was also a foreman on the construction of the Welland Canal and the Lachine Canal. While working on the Beauharnois Canal, a one-ton stone fell and crushed one of his legs. He recovered, but never regained the strength in that leg.

While in Kingston, Mackenzie became a vocal opponent of religious and political entitlement and corruption in government.

Mackenzie married Helen Neil (1826–52) in 1845 and with her had three children, with only one girl, Mary, surviving infancy.[1] Helen and he moved to Sarnia, Ontario (known as Canada West) in 1847 and Mary was born in 1848.[2] They were soon joined from Scotland by the rest of Mackenzie's brothers and his mother.[2] He began working as a general contractor, earning a reputation for being a hard-working, honest man, as well as having a working man's view on fiscal policy. Mackenzie helped construct many courthouses and jails across southern Ontario. A number of these still stand today, including the Sandwich Courthouse and Jail now known as the Mackenzie Hall Cultural Centre in Windsor, Ontario, and the Kent County Courthouse and Jail in Chatham, Ontario. He even bid, unsuccessfully, on the construction of the Parliament buildings in Ottawa in 1859.

Helen died in 1852, finally succumbing to the effects of excessive doses of mercury-based calomel used to treat a fever while in Kingston. In 1853, he married Jane Sym (1825–93).[1]

Mackenzie served as a Major in the 27th Lambton Battalion of Infantry from 1866 to 1874,[6] serving on active duty during the Fenian Raids in 1870.[7]

Early political involvement

editMackenzie involved himself in politics almost from the moment he arrived in Canada. He fought passionately for equality and the elimination of all forms of class distinction. In 1851, he became the secretary for the Reform Party for Lambton. After convincing him to run in Kent/Lambton, Mackenzie campaigned relentlessly for George Brown, owner of the Reformist paper The Globe in the 1851 election, helping Brown to win his first seat in the Legislative Assembly. Mackenzie and Brown remained the closest of friends and colleagues for the rest of their lives.

In 1852, Mackenzie became editor of another reformist paper, the Lambton Shield. As an editor, Mackenzie was perhaps a little too vocal, leading the paper to a lawsuit for libel against the local conservative candidate. Because a key witness claimed Cabinet Confidence and would not testify, the paper lost the suit and was forced to fold due to financial hardship.

After his brother, Hope Mackenzie, declined to run for re-election, Alexander was petitioned to run and won his first seat in the Legislative Assembly as a supporter of George Brown in 1861. When Brown resigned from the Great Coalition in 1865 over negotiations of a reciprocity trade treaty with the United States, Mackenzie was invited to replace him as president of the council. Wary of Macdonald's motivations and true to his principles, Mackenzie declined.

He entered the House of Commons of Canada in 1867, representing the Lambton constituency. No cohesive national Liberal Party of Canada existed at the time, and with Brown not winning his seat, no official leader emerged. Mackenzie was asked but did not believe he was the best qualified for the position. Although he resisted offers of the position, he nevertheless sat as the de facto leader of the Official Opposition.

Prime Minister (1873–1878)

editWhen the Macdonald government fell due to the Pacific Scandal in 1873, the Governor General, Lord Dufferin, called upon Mackenzie, who had been chosen as leader of the Liberal Party a few months earlier, to form a new government. Mackenzie formed a government and asked the Governor General to call an election for January 1874. The Liberals won a majority of the seats in the House of Commons having garnered 40% of the popular vote.

Mackenzie remained prime minister until the 1878 election when Macdonald's Conservatives returned to power.

For a man of Mackenzie's humble origins to attain such a position was unusual in an age which generally offered such opportunity only to the privileged. Lord Dufferin expressed early misgivings about a stonemason taking over government, but on meeting Mackenzie, Dufferin revised his opinions:

However narrow and inexperienced Mackenzie may be, I imagine he is a thoroughly upright, well-principled, and well-meaning man.

— Lord Dufferin

Mackenzie served concurrently as Minister of Public Works and oversaw the completion of the Parliament buildings. While drawing up the plans for the West Block, he included a circular staircase leading directly from his office to the outside of the building, which allowed him to escape the patronage-seekers waiting for him in his ante-chamber. Proving Dufferin's reflections on his character to be true, Mackenzie disliked intensely the patronage inherent in politics. Nevertheless, he found it a necessary evil to maintain party unity and ensure the loyalty of his fellow Liberals.

In keeping with his democratic ideals, Mackenzie refused the offer of a knighthood three times,[8] and was thus the only one of Canada's first eight Prime Ministers not to be knighted. He also declined appointment to the UK Privy Council and hence does not bear the title "Right Honourable". His pride in his working class origins never left him. Once, while touring Fort Henry as prime minister, he asked the soldier accompanying him if he knew the thickness of the wall beside them. The embarrassed escort confessed that he didn't and Mackenzie replied, "I do. It is five feet, ten inches. I know, because I built it myself!"[9]

As Prime Minister, Alexander Mackenzie strove to reform and simplify the machinery of government, achieving a remarkable record of reform legislation. He introduced the secret ballot; advised the creation of the Supreme Court of Canada; the establishment of the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston in 1874 and the creation of the Office of the Auditor General in 1878. He completed the Intercolonial Railway, but struggled to progress on the national railway due to a worldwide economic depression, almost coming to blows with Governor General Lord Dufferin over imperial interference. Mackenzie stood up for the rights of Canada as a nation and fought for the supremacy of Parliament and honesty in government. Above all else, he was known and loved for his honesty and integrity.

However, his term was marked by economic depression that had grown out of the Panic of 1873, which Mackenzie's government was unable to alleviate. In 1874, Mackenzie negotiated a new free trade agreement with the United States, eliminating the high protective tariffs in place on Canadian goods in US markets. However, this action did not bolster the economy, and construction of the CPR slowed drastically due to lack of funding. In 1876, the Conservative opposition announced a National Policy of protective tariffs, which resonated with voters. When an election was called in 1878, the Liberals got slightly more than a third of the vote, and the Conservatives with 42 percent of the votes came back into power.

Supreme Court appointments

edit

Mackenzie chose the following jurists to be appointed as justices of the Supreme Court of Canada by the Governor General:[10]

- Sir William Buell Richards (Chief Justice) – September 30, 1875

- Télesphore Fournier – September 30, 1875

- William Alexander Henry – September 30, 1875

- Sir William Johnstone Ritchie – September 30, 1875

- Sir Samuel Henry Strong – September 30, 1875

- Jean-Thomas Taschereau – September 30, 1875

- Sir Henri Elzéar Taschereau – October 7, 1878

Later life

editDespite his government's defeat, he retained the East York seat and remained Leader of the Opposition for another two years, until 1880. In 1881, he became the first president of The North American Life Assurance Company.

He was soon struck with a mysterious ailment that sapped his strength and all but took his voice. Although sitting in silence in the House of Commons, he held his House of Commons East York seat until his death in 1892.[11]

He suffered a stroke after hitting his head during a fall in 1892. He died on April 17 in Toronto at the age of seventy, and was buried in Lakeview Cemetery in Sarnia, Ontario.[8]

Character

editMackenzie's first biography in 1892 referred to him as Canada's Stainless Statesman.[12] He was a devout Baptist and teetotaller who found refuge in, and drew strength from, his family, friends, and faith.[13][2] He was also a loyal friend and an incorrigible prankster (stuffed chimney on young in-laws; rolled boulder down Thunder Cape towards friend A. McKellar; burned Tory campaign placards in hotel woodstove early in morning).[14]

Unpretentious and down to earth,[15] his public official austerity was in striking contrast to private compassion and giving nature.[16] He was the soul of honour and integrity,[17] a proud man who sought no recognition or personal enrichment and accepted gifts reluctantly.[18] He preferred to follow than to lead (many times he refused leadership offers) and he said he found that duty outweighed the heavy burden of office.[19] He was uncompromising on his principles, perhaps too much so.[20] An historian at the time said, "He was, and ever will remain, the Sir Galahad of Canadian politics."[21]

Very proud of his Scottish heritage, he was forever a Scot: "Nemo me impune lacessit" (no one attacks me with impunity).[22] The Upper Canada rebellion leader William Lyon Mackenzie said of him, "He is every whit a self-made, self-educated man. Has large mental capacity and indomitable energy." [23]

Canada's Governor General, Lord Dufferin, said he was "as pure as crystal, and as true as steel, with lots of common sense."[24] A close friend, Chief Justice Sir Louis Davies, said he was "the best debater the House of Commons has ever known."[25] Sir Wilfrid Laurier, a friend, colleague in cabinet and later prime minister of Canada, said Mackenzie was "one of the truest and strongest characters to be met within Canadian history. He was endowed with a warm heart and a copious and rich fancy, though veiled by a somewhat reticent exterior, and he was of friends the most tender and true."[26]

Sir George Ross, a friend, colleague, and later premier of Ontario, said, "Mackenzie was sui generis a debater. His humorous sallies blistered like a blast from a flaming smelter. His sterling honesty is a great heritage, and will keep his memory green to all future generations."[27]

At his eulogy, Rev. Dr. Thomas compared him to the Duke of Wellington, who "stood four square, to all the winds that blow."[28]

Newspapers around the world and in Canada gave him many compliments. The London Times – the untiring energy, the business-like accuracy, the keen perception and reliable judgment, and above all the inflexible integrity, which marked his private life, he carried without abatement of one jot into his public career.[29] The Westminster Review – a man, who although, through failing health and failing voice, he had virtually passed out of public life, yet retained to the last the affectionate veneration of the Canadian people as no other man of the time can be said to have done.[30][31]

The Charlottetown Patriot – in all that constitutes the real man, the honest statesman, the true patriot, the warm friend, and sincere Christian, he had few equals. Possessed of a clear intellect, a retentive memory, and a ready command of appropriate words, he was one of the most logical and powerful speakers we have ever heard.[32]

The St. John Telegraph – he was loved by the people and his political opponents were compelled to respect him even above their own chosen leader. As a statesman, he has had few equals.[33]

The Montreal Star – it is one of the very foremost architects of the Canadian nationality that we mourn. In the dark days of ’73, Canadians were in a state of panic, distrusting the stability of their newly-built Dominion; no one can tell what would have happened had not the stalwart form of Alexander Mackenzie lifted itself above the screaming, vociferating and denying mass of politicians, and all Canada felt at once, there was a man who could be trusted.[34]

The Toronto Globe – he was a man who loved the people and fought for their rights against privilege and monopoly in every form.[34] The Philadelphia Record – Like Caesar, who twice refused a knightly crown, Alexander Mackenzie refused knighthood three times. Unlike Caesar, he owed his political overthrow to his incorruptible honesty and unswerving integrity.[33]

Legacy

editIn their 1999 study of the Prime Ministers of Canada, which included the results of a survey of Canadian historians, J. L. Granatstein and Norman Hillmer found that Mackenzie was in 11th place just after John Sparrow David Thompson.[35]

Namesakes

edit

The following are named in honour of Alexander Mackenzie:

- The Mackenzie Mountain Range in the Yukon and Northwest Territories

- Mount Mackenzie, in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia

- The Mackenzie Building, and the use of the Mackenzie tartan by the bands at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario, "Alexander Mackenzie", the Royal Military College of Canada March for bagpipes, was composed in his honour by Pipe Major Don M. Carrigan, who was the College Pipe Major 1973 to 1985.[36]

- Mackenzie Hall in Windsor, Ontario

- Alexander Mackenzie Scholarships in Economics and Political Science at McGill University and the University of Toronto

- Alexander MacKenzie Park in Sarnia, Ontario[37]

- Alexander Mackenzie High School in Sarnia

- Alexander Mackenzie Housing Co-Operative Inc. in Sarnia

- Mackenzie Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario

- Mackenzie Tower, West Block, Parliament Hill, Ottawa, Ontario

Other honours

edit- A monument is dedicated to his tomb in Lakeview Cemetery, Sarnia, Ontario

- "Honourable Alexander Mackenzie" (1964) by Lawren Harris, head of the Department of Fine Arts, Mount Allison University, now hangs in the Mackenzie Building, Royal Military College of Canada. The unveiling ceremony was performed by the Right Honourable Louis St. Laurent, a Canadian former Prime Minister, and the gift was accepted by the Commandant, Air Commodore L.J. Birchall. The painting was commissioned in memory of No. 244, Lieut.-Col, F.B. Wilson, O.B.E., her deceased husband, by Mrs, F.W. Dashwood. Also taking part in the ceremony was the Honourable Paul Hellyer, Minister of National Defence, President and Chancellor of the college.[38] In attendance was Mrs. Burton R. Morgan of Ottawa, great-granddaughter of Alexander Mackenzie.

- Burgess tickets presented to Alexander Mackenzie in Dundee, Dunkeld, Logierait, Irvine, and Perth Scotland.

Electoral record

editSee also

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ a b c Harris (1893), p. 136.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Forster (1990).

- ^ Thomson (1960), p. 12.

- ^ Chisholm (1911).

- ^ Blarg (1950).

- ^ Blatherwick, John. "Prime Ministers of Canada – Their Military Connections, Honours and Medals" (PDF). National Defence Historical Department. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Lambton County Historical Society (2020). "St. Clair Borderers (Military pre-World War 1". Lambton County Museums. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Honourable Alexander Mackenzie". Former Prime Ministers and Their Grave Sites. Parks Canada. October 3, 2017. Archived from the original on December 11, 2017.

- ^ Canada's Prime Ministers, 1867 – 1994: Biographies and Anecdotes. [Ottawa]: National Archives of Canada, [1994]. 40 p.

- ^ Snell, James G.; Vaughan, Frederick (1985). "The Founding of the Court 1867–1879". The Supreme Court of Canada: History of the Institution. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 3–27. ISBN 9780802034182. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctvfrxdfw.5.

- ^ NRCS.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), dedication introduction.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), pp. 55, 93, 100.

- ^ Thomson (1960), pp. 18, 87.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), pp. 99, 633, 660.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), pp. 99–100.

- ^ Marquis (1903), p. 401.

- ^ Thomson (1960), pp. 354, 367.

- ^ Thomson (1960), p. 343; Buckingham & Ross (1892), pp. 294, 441, 631

- ^ Marquis (1903), p. 460; Buckingham & Ross (1892), pp. 211, 518; Forster (1990)

- ^ Marquis (1903), p. 418.

- ^ Ross (1913), p. 56.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 120.

- ^ Thomson (1960), p. 211.

- ^ (Mackenzie's newspaper scrapbook "Days of Giants", Library and Archives Canada).

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 633.

- ^ Ross (1913), p. 31.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 643, quoting Tennyson’s "Ode to the Death of the Duke of Wellington".

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 663.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 651.

- ^ The Westminster Review. Vol. 137. London: Edward Arnold. 1892. p. 651.

- ^ Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 662.

- ^ a b Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 660.

- ^ a b Buckingham & Ross (1892), p. 661.

- ^ Hillmer, Norman; Granatstein, J. L. "Historians rank the BEST AND WORST Canadian Prime Ministers". Diefenbaker Web. Maclean's. Archived from the original on July 19, 2001. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Archie Cairns – Bk1 Pipe Music 'Alexander Mackenzie' (Slow March) by Pipe Major Don M. Carrigan 1995

- ^ Mackenzie, Hon. Alexander National Historic Person. Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Parks Canada.

- ^ Source: Royal Military College of Canada – Review Yearbook (Kingston, Ontario Canada) Class of 1965, page 191

Works cited

edit- Buckingham, William; Ross, George William (1892). The Honourable Alexander Mackenzie: His Life and Times. Toronto: Rose Publishing.

- Forster, Ben (1990). "Mackenzie, Alexander". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XII (1891–1900) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Harris, Charles Alexander (1893). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 35. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 135–136.

- Marquis, T.G. (1903). Builders of Canada from Cartier to Laurier. Brantford, Ontario: Bradley-Garretson. pp. 392–418.

- Ross, Sir George W. (1913). Getting into Parliament and After. Toronto: William Briggs.

- Thomson, Dale C. (1960). Alexander Mackenzie, Clear Grit. Macmillan of Canada.

- NRCS. "Melissa officinalis". PLANTS Database. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 6 July 2015.

General sources

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251.

- Alexander Mackenzie fonds at Library and Archives Canada

Further reading

edit- Bumsted, J.M. (March 7, 2018). "Alexander Mackenzie". The Canadian Encyclopedia (online ed.). Historica Canada.

- Dent, John Charles (1880). The Canadian Portrait Gallery. Vol. 1. Toronto: John B. Magurn.

- Granatstein, J.L; Hillmer, Norman (1999). Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada's Leaders. Toronto: Harper Collins. pp. 29–36. ISBN 978-0-0063-8563-9..