Tentacle erotica (触手責め, shokushu zeme, "tentacle attack") is a type of pornography most commonly found in Japan that integrates traditional pornography with elements of bestiality, fantasy, horror, and science fiction. It is found in some horror or hentai titles, with tentacled creatures (usually fictional monsters) having sexual intercourse, predominantly with females or, to a lesser extent, males. Tentacle erotica can be consensual but mostly contains elements of rape.

The genre is well known enough in Japan that it is the subject of parody. In the 21st century, Japanese films of this genre have become recognized in the United States and Europe, although it remains a small, fetish-oriented part of the adult film industry. While most tentacle erotica is animated, there are also a few live-action films that depict it.

History

editThe earliest examples of tentacle erotica were woodblock prints depicting women being violated by octopuses, such as Kitao Shigemasa's Programme of Erotic Noh Plays (1781) and Shunshō Katsukawa's Lust of Many Women on One Thousand Nights (1786).[1]

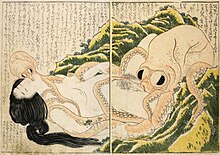

Another early instance is an illustration from the 1814 Hokusai book Kinoe no Komatsu, known as The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife. It is an example of shunga (Japanese erotic woodblock art) and has been reworked by a number of artists,[2] such as Masami Teraoka, who brought the image up to date with his 2001 work "Sarah and Octopus/Seventh Heaven", which was part of his Waves and Plagues collection.

While Western audiences in many cases interpret Hokusai's famous design as rape, Japanese audiences of the Edo period would have viewed it as consensual, recognizing the print as depicting the legend of the female abalone diver Tamatori.[3] In the story, Tamatori steals a jewel from the Dragon King. During her escape, the Dragon King and his sea-life minions (including octopuses) pursue her. The dialogue in the illustration shows the diver and two octopuses expressing mutual enjoyment.

Contemporary censorship in Japan dates to the Meiji period. The influence of European Victorian culture was a catalyst for legislative interest in public sexual practices. After World War II, the Allies imposed a number of reforms on the Japanese government, including censorship laws. The legal proscriptions against pornography, therefore, derive from the nation's penal code. Presently, "obscenity" is still prohibited. How this term is interpreted, however, has not remained constant. While exposed genitalia (and, until recently, pubic hair) is illegal, the diversity of permissible sexual acts is now fairly wide, relative to other liberal democracies.[citation needed]

Leaders within the tentacle porn industry have stated that much of their work was initially directed at circumventing this policy. According to the mangaka Toshio Maeda:

At that time pre-Urotsukidōji, it was illegal to create a sensual scene in bed. I thought I should do something to avoid drawing such a normal sensual scene. So I just created a creature. His tentacle is not a penis as a pretext. I could say, as an excuse, this is not a penis; this is just a part of the creature. You know, the creatures, they don't have a gender. A creature is a creature. So it is not obscene – not illegal.[4]

Culture

editAnimation

editThe earliest animated form of tentacle erotica was in the 1985 original video animation (OVA) Dream Hunter Rem, though the scene in question was excised when the OVA was re-released in a form with sexual scenes removed. The first purely non-erotic anime portraying a tentacle assault would be the 1986 anime OVA Guyver: Out of Control, where a female Chronos soldier named Valcuria is enshrouded by the second (damaged) Guyver unit that surrounds her in tentacle form and assaults her.[citation needed]

Numerous animated tentacle erotica films followed in the next couple decades. Popular titles like 1986's Urotsukidoji, 1992's La Blue Girl, and 1995's Demon Beast Resurrection became common sights in large video store chains in the United States and elsewhere. The volume of films in this genre has slowed since the peak years in the 1990s, but they continue to be produced through the present day.

Manga

editWhile manga has featured stories of heroes being attacked by monsters with tentacles since its early days, the earliest examples of tentacle erotica in manga belong to "real life" erotic comedy manga magazines, which predate ero-gekiga. Multiple scenes were found in the March 12, 1968 issue of Weekly Manga Q, where several creatures with tentacles attacked women. Another early example belonged to Osamu Tezuka's sci-fi story The Returnees (1973), where a scene depicts a woman being assaulted and impregnated by a space creature.[5]

Toshio Maeda's Urotsukidōji was a pioneer in the tentacle rape genre with its mix of sex, bishōjo and tentacles. Maeda's depiction of tentacles was more creature-like and possessed at will, imitating male genitalia. However, six years prior to Urotsukidōji in 1976, Maeda created his first tentacle work in an experimental short story called SEX Tearing, which is considered the origin for Urotsukidōji as well as the earliest work depicting sex between women and tentacles.[6][7] In 1989, Maeda's manga Demon Beast Invasion created what could be considered the modern Japanese paradigm of tentacle porn, in which the elements of sexual assault are emphasized. Maeda explained that he invented the practice to get around strict Japanese censorship regulations, which prohibit the depiction of the penis but do not prohibit showing sexual penetration by a tentacle or similar appendages.

Live action

editThe use of sexualized tentacles in live-action films, while much rarer, started in American B-movie horror films and has since migrated to Japan.[citation needed] B-movie producer Roger Corman used the concept of tentacle rape in a brief scene in his 1970 film The Dunwich Horror, a film adaptation of the H. P. Lovecraft short story of the same name. Vice magazine identifies this as "perhaps cinema history's first tentacle-rape scene".[8]

A decade later, Corman would again use tentacle rape while producing Galaxy of Terror, released in 1980. Corman also directed a scene in which actress Taaffe O'Connell, playing an astronaut on a future space mission, is captured, raped, and killed by a giant, tentacled worm. The film borrows the concept of the "Id Monster" from the 1950s film Forbidden Planet, with the worm being a manifestation of O'Connell's character's fears. The scene was graphic enough that the film's director, B. D. Clark, refused to helm it, and O'Connell refused to do the full nudity required by Corman, so Corman directed the scene himself and used a body double for some of the more graphic shots. Initially given an X-rating by the Motion Picture Association of America, small cuts were made to the scene, which changed the film's rating to "R.".

Sam Raimi's The Evil Dead includes a scene where actress Ellen Sandweiss' character is attacked by the possessed woods she walks through. The evil spirit inhabiting the woods uses tree limbs and branches to ensnare, strip, and rape her, possessing her through the sexual acts in a way reminiscent of that in which tentacles are depicted in other pieces of media.[9] The scene was repeated in a shorter version in the sequel, Evil Dead II, released in 1987.

The 1981 Japanese film Edo Porn, about the life of artist Katsushika Hokusai, featured the Dream of the Fisherman's Wife painting in a live-action depiction. In the 1981 film Possession, a woman copulates with a tentacled creature, although the tentacles themselves are never explicitly shown to penetrate her.[citation needed]

The popularity of these films has led to the subsequent production of numerous live-action tentacle films in Japan from the 1990s to the present day. The theme rarely appears in adult American cinema and art; one example is American artist Zak Smith, who painted several works featuring octopuses and porn stars in various stages of intercourse.[10][11] In 2016, Amat Escalante directed the art-house film The Untamed, which depicts a live-action scene between the female protagonist and a tentacled space alien.[12]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Kimi, Rito (2021). The History of Hentai Manga: An Expressionist Examination of Eromanga. FAKKU. pp. 137, 138. ISBN 978-1-63442-253-6.

- ^ Courage, Katherine Harmon (2013). "Tentacle Erotica". Octopus!: The Most Mysterious Creature in the Sea. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780698137677.

- ^ Talerico, Danielle. "Interpreting Sexual Imagery in Japanese Prints: A Fresh Approach to Hokusai's Diver and Two Octopi", in Impressions, The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Vol. 23 (2001).

- ^ Manga Artist Interview Series (Part 1), 2002

- ^ Kimi, Rito (2021). The History of Hentai Manga: An Expressionist Examination of Eromanga. FAKKU. pp. 141, 142. ISBN 978-1-63442-253-6.

- ^ Kimi, Rito (2021). The History of Hentai Manga: An Expressionist Examination of Eromanga. FAKKU. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-63442-253-6.

- ^ Kimi, Rito (2021). The History of Hentai Manga: An Expressionist Examination of Eromanga. FAKKU. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-63442-253-6.

- ^ Eil, Philip (August 20, 2015). "The Posthumous Pornification of H. P. Lovecraft". Vice. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ Scherer, Agnes (2016). Plant Horror: Approaches to the Monstrous Vegetal in Fiction and Film. Springer Publishing. p. 41. ISBN 9781137570635.

- ^ "Zak Smith - Artist - Saatchi Gallery". www.saatchigallery.com. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ "Porn thai". Thai Porns. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (2017-08-17). "The Untamed review – a film about love, pleasure and a tentacular sex monster". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2023-07-07.

External links

edit- Manga Artist Interview Series Part I, Sake-Drenched Postcards—interview with Toshio Maeda.