Moondance is the third studio album by Northern Irish singer-songwriter Van Morrison. It was released on 27 January 1970 by Warner Bros. Records. After the commercial failure of his first Warner Bros. album Astral Weeks (1968), Morrison moved to upstate New York with his wife and began writing songs for Moondance. There, he met the musicians that would record the album with him at New York City's A & R Studios in August and September 1969.

| Moondance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | January 27, 1970 | |||

| Recorded | August–September 1969 | |||

| Studio | A & R (New York) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 38:14 | |||

| Label | Warner Bros. | |||

| Producer | Van Morrison | |||

| Van Morrison chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Moondance | ||||

| ||||

The album found Morrison abandoning the abstract folk jazz compositions of Astral Weeks in favour of more formally composed songs, which he wrote and produced entirely himself. Its lively rhythm and blues/rock music was the style he would become most known for in his career. The music incorporated soul, jazz, pop, and Irish folk sounds into songs about finding spiritual renewal and redemption in worldly matters such as nature, music, romantic love, and self-affirmation.

Moondance was an immediate critical and commercial success. It helped establish Morrison as a major artist in popular music, while several of its songs became staples on FM radio in the early 1970s. Among the most acclaimed records in history, Moondance frequently ranks in professional listings of the greatest albums. In 2013, the album's remastered deluxe edition was released to similar acclaim.

Background

editAfter leaving the rock band Them, Morrison met record producer Bert Berns in New York City and recorded his first solo single, "Brown Eyed Girl", in March 1967 for Berns' Bang Records. When the producer unexpectedly died later that year, Morrison was offered a record deal by Warner Bros. Records executive Joe Smith, who had seen the singer perform at Boston's Catacombs nightclub in August 1968. Smith bought out Morrison's Bang contract, and he was able to record his first album for Warner Bros., Astral Weeks, that year.[1] Although it was later acclaimed by critics, its collection of lengthy, acoustic, revelatory folk jazz songs was not well received by consumers at the time and the album proved to be a commercial failure.[2]

After recording Astral Weeks, Morrison moved with his wife, Janet Planet, to a home on a mountain top in the Catskills near Woodstock, a hamlet in upstate New York with an artistic community.[3] According to Planet, he was influenced by Bob Dylan, who had just moved out of town when Morrison arrived. "Van fully intended to become Dylan's best friend", Planet recalled. "Every time we'd drive past Dylan's house ... Van would just stare wistfully out the window at the gravel road leading to Dylan's place. He thought Dylan was the only contemporary worthy of his attention."[4]

Morrison began writing songs for Moondance in July 1969.[5] Because of Astral Weeks's poor sales figures, the singer wanted to produce a record that would be more accessible and appealing to listeners. "I make albums primarily to sell them and if I get too far out a lot of people can't relate to it", he later said. "I had to forget about the artistic thing because it didn't make sense on a practical level. One has to live."[6] The musicians who went on to record Moondance with Morrison were recruited from Woodstock and would continue working with him for several years, including guitarist John Platania, saxophonist Jack Schroer, and keyboardist Jef Labes.[7] The singer left after the Woodstock music festival in August attracted an influx of people to the area.[8]

Recording and production

editMorrison began recording sessions for Moondance at Century Sound in New York, accompanied by most of the musicians from Astral Weeks and its engineer Brooks Arthur.[4] Lewis Merenstein—Moondance's executive producer—had brought in Astral Weeks session musicians Richard Davis, Jay Berliner, and Warren Smith, Jr. for the first session, but Morrison—according to Platania—"sort of manipulated the situation" and "got rid of them all. For some reason he didn't want those musicians."[9] In place of these jazz-influenced musicians were a horn section and chorus enlisted by Morrison, who Merenstein recalled had grown more confident, outspoken, and independent of the producer.[4] Around this time, the singer made it known to Warner Bros. that he would lead production duties for all his future recordings, which forced producers recruited by the label into assisting roles. It also led to frequent enlisting and dismissal of musicians to meet Morrison's creative vision.[10]

Morrison went on to record Moondance at the Studio A penthouse of A & R Studios in New York from August to September 1969.[11] He entered A & R Studios with only the basic song structures written down and the songs' arrangements in his memory, developing the compositions throughout the album's recording. Without any musical charts, he received help with developing the music from Labes, Schroer, and flautist/saxophonist Collin Tilton.[5] "That was the type of band I dig", the singer recalled. "Two horns and a rhythm section – they're the type of bands that I like best."[12] According to biographer Ritchie Yorke, all of the "tasteful frills" were generated spontaneously and developed at the studio.[5] Most of Morrison's vocals were recorded live, and he later said that he would have preferred to record the entire album live.[5] Shelly Yakus—one of the audio engineers who recorded the singer—remembered him being "very quiet and really introverted" in the studio, "yet when he sang it was a 'Holy Shit!' moment."[11]

Moondance was the first album for which Morrison was credited as the producer; he later said "no one knew what I was looking for except me, so I just did it."[5] While not an overbearing presence among the record's personnel, the singer later conceded to creating an atmosphere of artistic autonomy during the sessions: "When I go into the studio, I'm a magician. I make things happen. Whatever is working in that particular space at that particular time, I use, I take advantage of."[10]

Music and lyrics

editFor Moondance, Morrison abandoned the abstract folk compositions of Astral Weeks in favour of rhythm and blues sounds, formally composed songs, and more distinct arrangements that included a horn section and chorus of singers as an accompaniment.[13] The album found Morrison using more traditional melodic figures, which VH1 editor Joe S. Harrington said lent the songs a "rustic and earthy" quality.[14] In Robert Christgau's opinion, Moondance showed the singer integrating his style of Irish poetry into popular song structure while expanding on Astral Weeks' "folk-jazz swing" with lively brass instruments, innovative hooks, and a strong backbeat.[15] The songs were generally arranged around Morrison's horn section; music journalist John Milward called it "that rare rock album" on which the solos were performed by the saxophonist rather than the guitarist.[16] In The Rolling Stone Album Guide (1992), Paul Evans observed upbeat soul music, elements of jazz, and ballads on what he considered a "horn-driven, bass-heavy" record.[17] Rob Sheffield said it debuted the musical style Morrison would become known for—a "mellow, piano-based" fusion of jazz, pop, and Irish folk styles.[18]

More structured and direct than its predecessor, [Moondance] somehow feels just as loose and free. This is Van Morrison's 6th Symphony; like Beethoven's equivalent, it's fixated on the power of nature, but rather than merely sitting in awe, it finds spirituality and redemption in the most basic of things.

—Nick Butler, Sputnikmusic[19]

Morrison's lyrics on Moondance deal with themes of spiritual renewal and redemption.[20] It departed from Astral Weeks' discursive, stream-of-consciousness narratives as the singer balanced his spiritual ideas with more worldly subject matter, which biographer Johnny Rogan felt offered the record a quality of "earthiness".[21] As a counterpart to Astral Weeks, AllMusic critic Jason Ankeny believed it "retains the previous album's deeply spiritual thrust but transcends its bleak, cathartic intensity" by rejoicing in "natural wonder".[20] According to Christgau, the essence of Morrison's spirit was, much like the African-American music that inspired him, "mortal and immortal simultaneously: this is a man who gets stoned on a drink of water and urges us to turn up our radios all the way into the mystic."[15] His "giddy" preoccupation with "natural wonder" on the album was a product of the new approach to composition and the mellow feel of his new band, Harrington said. In his opinion, the record's exuberant spirit and theme of self-affirmation were partly inspired by the singer having "settled into a life of domestic bliss".[22] Musicologist Brian Hinton argued that Morrison was celebrating a "natural alternative" in his music after quitting soft drugs around this time because they had impeded his productivity.[23]

Songs

editThe opening song, "And It Stoned Me", was written about feelings of ecstasy received from witnessing and experiencing nature, in a narrative describing a rural setting with a county fair and mountain stream. Morrison said he based it on a quasi-mystical experience he had as a 12-year-old fishing in the Comber village of Ballystockart, where he once asked for water from an old man who said he had retrieved it from a stream. "We drank some and everything seemed to stop for me", the singer recalled, adding that it induced a momentary feeling of quietude in him. According to Hinton, these childhood images foreshadowed both spiritual redemption and—in Morrison's reference to "jellyroll" in the chorus—sexual pleasure.[23] AllMusic's Tom Maginnis argued that the singer was instead likening the experience to the first time hearing jazz pianist Jelly Roll Morton.[24] The largely acoustic title track "Moondance" featured piano, guitar, saxophone, electric bass, and a flute over-dub backing Morrison, who sang of an adult romance set in Autumn and imitated a saxophone with his voice near the song's conclusion. "This is a rock musician singing jazz, not a jazz singer, though the music itself has a jazz swing", Hinton remarked.[25] "Crazy Love" was recorded with Morrison's voice so close to the microphone that it captured the click of Morrison's tongue hitting the roof of his mouth as he sang.[26] He sings in falsetto, producing what Hinton felt was a sense of intense intimacy, backed by a female chorus.[27]

"Caravan" and "Into the Mystic" were cited by Harrington as examples of Morrison's interest in "the mystifying powers of the music itself" throughout Moondance.[14] The former song thematises music radio and gypsy life—which fascinated the singer—as symbols of harmony.[27] Harrington called it an ode to "the transcendent powers of rock 'n' roll and the spontaneous pleasures of listening to a great radio station", while biographer Erik Hage regarded it as "a joyful celebration of communal spirit, the music of radio, and romantic love".[28] "Into the Mystic" reconciles Moondance's R&B style with the more orchestrated folk music of Astral Weeks, along with what Evans described as "the complementary sides of Morrison's psyche".[17] Harrington believed it explores "the intricate balance between life's natural wonder and the cosmic harmony of the universe".[14] Hinton said the song evoked a sense of "visionary stillness" shared with "And It Stoned Me" and the gypsy imagery of "Caravan", while working on several other interpretive levels. Its images of setting sail and water in particular represented "a means of magical transformation" for the writer, comparable to Alfred Lord Tennyson's poems of leave-taking such as "Crossing the Bar", which had "the same sense of crossing over, both to another land and into death". The lyrics also deal with "the mystical union of good sex", and an act of love Hinton said was intimated by Morrison's closing vocal "too late to stop now"—a phrase the singer would use to conclude his concerts in subsequent years.[29]

"Come Running" was described by Morrison as "a very light type of song. It's not too heavy; it's just a happy-go-lucky song." By contrast, Hinton found the song's sentiments tender and lustful in the vein of the 1967 Bob Dylan song "I'll Be Your Baby Tonight". He argued that "Come Running" juxtaposed images of unstoppable nature—wind and rain, a passing train—against "which human life and death play out their little games", and in which the narrator's and his lover's dream will not end "while knowing of course it will".[30] According to the writer, "These Dreams of You" manages to be simultaneously accusatory and reassuring. The lyrics cover such dream sequences as Ray Charles being shot down, paying dues in Canada, and "his angel from above" cheating while playing cards in the dark, slapping him in the face, ignoring his cries, and walking out on him. Morrison said he was inspired to write "Brand New Day" after hearing the Band on the radio playing either "The Weight" or "I Shall Be Released": "I looked up at the sky and the sun started to shine and all of a sudden the song just came through my head. I started to write it down, right from 'When all the dark clouds roll away'."[31] Yorke quoted Morrison as saying in 1973 that "Brand New Day" was the song that worked best to his ear and the one with which he felt most in touch.[32]

Along with "Brand New Day", "Everyone" and "Glad Tidings" form a closing trio of songs permeated by what John Tobler called "a celebratory air, bordering on spiritual joy".[8] Labes opened "Everyone" by playing a clavinet figure in 6

8 time. A flute comes in, playing the melody after Morrison has sung four lines, with Schroer playing the harmony underneath on soprano saxophone. Although Morrison says the song is just a song of hope, Hinton says its lyrics suggest a more troubled meaning, as 1969 was the year in which The Troubles broke out in Belfast.[31] The final track, "Glad Tidings", has a bouncy beat but the lyrics, like "Into the Mystic", remain largely impenetrable, according to Hinton. In his opinion, "the opening line and closing line, 'and they'll lay you down low and easy', could be either about murder or an act of love."[33] In Hage's opinion, "'Glad Tidings' was a premonition of the future, as for the next four decades, Morrison would continue to use a song here and there to vent about the evils of the music industry and the world of celebrity."[34]

Packaging

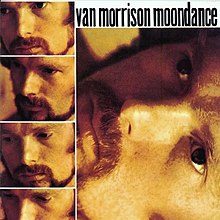

editThe album's cover photo was shot at Morrison's home by Elliot Landy, who had previously done the cover for Dylan's 1969 album Nashville Skyline. Landy captured Morrison's face closely and framed the shot to conceal a sizeable pimple the singer had on his forehead the day of the shoot.[4]

Planet wrote the album's liner notes, drawing on the style of fairy tales in narrating Morrison's story; the notes began, "Once upon a time, there lived a very young man who was, as they say, gifted". According to Planet, Warner Bros. encouraged her to help promote him, believing "that my image, precisely because it was so enigmatic, was the perfect visual to describe what was going on musically". In retrospect, she found that "being a muse is a thankless job, and the pay is lousy."[4]

Release and reception

editMoondance was released by Warner Bros. on 27 January 1970 in the United Kingdom and on 28 February in the United States, receiving immediate acclaim from critics.[35] Reviewing for The Village Voice in 1970, Robert Christgau gave the album an "A" and claimed that Morrison had finally fulfilled his artistic potential: "Forget Astral Weeks—this is a brilliant, catchy, poetic, and completely successful LP."[36] Greil Marcus and Lester Bangs jointly reviewed the album in Rolling Stone, hailing it as a work of "musical invention and lyrical confidence; the strong moods of 'Into the Mystic' and the fine, epic brilliance of 'Caravan' will carry it past many good records we'll forget in the next few years."[37] Fellow Rolling Stone critic Jon Landau found the singer's vocals overwhelming: "Things fell into place so perfectly I wished there was more room to breathe. Morrison has a great voice and on Moondance he found a home for it."[33] Ralph J. Gleason from the San Francisco Chronicle also wrote of Morrison's singing as a focal point of praise: "He wails as the jazz musicians speak of wailing, as the gypsies, as the Gaels and the old folks in every culture speak of it. He gets a quality of intensity in that wail which really hooks your mind, carries you along with his voice as it rises and falls in long, soaring lines."[37]

After the commercial failure of Astral Weeks, Moondance was seen by music journalists as a record that redeemed Morrison.[38] Billboard magazine predicted it would reach rock and folk audiences while rectifying music buyers' oversight of the singer's previous record "with a more commercial entry, still rich with the soul-folk nuances of this sensitive Irish song surrealist".[39] Moondance reached the top 30 of the American albums chart and the top 40 of the British chart in 1970, while establishing Morrison as a young, commercially successful, and artistically independent singer-songwriter with great promise.[40] Its eclectic, lushly arranged style of music proved more accessible to listeners and translatable for live audiences, leading Morrison to form the Caledonia Soul Orchestra, a large ensemble of musicians with whom he would find his greatest concert success.[41] According to Harrington, Moondance was very successful with hippie couples who were "settling into complacent domesticity" at the time.[14] In Hage's opinion, its success lent Morrison a rising cultural iconicity and presence in the burgeoning singer-songwriter movement of the early 1970s, first indicated by his front cover feature on the July 1970 issue of Rolling Stone.[42]

Legacy and reappraisal

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [20] |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A+[15] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [43] |

| The Great Rock Discography | 9/10[44] |

| Los Angeles Times | [45] |

| Music Story | [46] |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[47] |

| Pitchfork | 8.4/10[4] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [17] |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[48] |

In artistic and commercial terms, Moondance would "practically define [Morrison] in the public consciousness for decades to follow", according to Hage.[41] It made the singer a popular radio presence in the 1970s, as several of its songs became FM airplay staples, including "Caravan", "Into the Mystic", the title track, and "Come Running", which was a top 40 hit in the US.[49] Some songs from the album became hits for other recording artists, such as Johnny Rivers' 1970 cover of "Into the Mystic" and the 1971 "Crazy Love" recording by Helen Reddy.[8] Moondance was also a precursor to the decade's adult-oriented rock radio format—typified by the music of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, James Taylor, and Paul McCartney—and the first hit album for mixing engineer Elliot Scheiner, who went on to have a prolific career engineering some of the 1970s' most popular recording artists.[50] In summarising the album's legacy, Ryan H. Walsh wrote in Pitchfork:

The album would solidify Van Morrison as an FM radio mainstay, act as a midwife for the burgeoning genre of 'soft rock,' and help usher in the '70s in America, where the beautiful hippie couples of the late '60s would soundtrack their developing newfound domestic comfort with the sweet sounds of Morrison's mystical love-anthems.[4]

Although the album never topped the record charts, it sold continuously for the next 40 years of its release, particularly after its digitally remastered reissue in 1990.[51] In 1996, Moondance was certified triple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America, having shipped three million copies in the US.[52]

In the years following the original release, Moondance has been frequently ranked as one of the greatest albums ever.[53] In 1978, it was voted the 22nd best album of all time in Paul Gambaccini's poll of 50 prominent American and English rock critics.[54] Christgau, one of the critics polled, named it the 7th best album of the 1970s in The Village Voice the following year.[55] In a retrospective review, Nick Butler from Sputnikmusic considered Moondance to be the peak of Morrison's career and "maybe of non-American soul in general", while Spin deemed it "the great white soul album" in an essay accompanying the magazine's 1989 list of the all-time 25 greatest albums, on which Moondance was ranked 21st.[56] In 1999, the album was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame, and in 2003, it was placed at number 65 on Rolling Stone's list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[57][nb 1] The album was also included in the 2000 edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (where it placed at number 79), the music reference book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (2005), and Time magazine's 2006 list of the "All-TIME 100 Albums".[59] The following year, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame named Moondance one of their "Definitive 200" albums, ranking it 72nd.[60] In 2009, Hot Press polled numerous Irish recording artists and bands, who voted it the 11th best Irish album of all time.[61]

2013 reissue

editA deluxe edition of Moondance was released by Warner Bros. on 22 October 2013. It featured a newly remastered version of the original record, three CDs of previously unreleased music from the recording sessions, and a Blu-ray disc with high-resolution audio of the original album. The packaging included a linen-wrapped folio and a booklet with liner notes written by Scheiner and music journalist Alan Light.[46] Select alternate takes from the deluxe edition were later compiled, along with previously unreleased mixes of "And It Stoned Me" and "Crazy Love", for The Alternative Moondance, an album conceived as an alternate version of the original record and released exclusively in vinyl format for Record Store Day in April 2018.[62]

The 2013 deluxe reissue was met with widespread critical acclaim; Record Collector called it an aural "marvel", while The Independent said the remastering "strips away centuries of digital compression and makes the music sound as if you've never heard it properly".[63] In Rolling Stone, Will Hermes felt the numerous outtakes possessed an intimate quality that compensated for lacking the "sublime, brassy" arrangements featured on the final version of Morrison's "jazzy-pop masterpiece".[64] Morrison, however, disowned the release as "unauthorised" and done without his consultation while claiming his management company had given away the rights to the music in the early 1970s.[65]

Track listing

editAll songs were written by Van Morrison, except where noted.[66]

1970 LP

edit

2013 deluxe CDedit

|

- Disc five is a Blu-ray audio version of disc one, rendered in 24-bit/192 kHz high-resolution, 5.1 surround sound.[66]

The Alternative Moondance LP (2018)

edit

|

Personnel

editCredits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[66]

Musicians

- Judy Clay – backing vocals ("Crazy Love" and "Brand New Day")

- Emily Houston – backing vocals ("Crazy Love" and "Brand New Day")

- John Klingberg – bass

- Jef Labes – clavinet, organ, piano

- Gary Mallaber – drums, percussion, vibraphone

- Guy Masson – congas

- Van Morrison – harmonica, production, rhythm guitar, tambourine, vocals

- John Platania – guitar

- Jack Schroer – alto and soprano saxophones

- Collin Tilton – flute, tenor saxophone

- Jackie Verdell – backing vocals ("Crazy Love" and "Brand New Day")

Production

- Craig Anderson – Blu-ray authoring (deluxe edition)

- Bob Cato – design

- Wyn Davis – additional mixing and mastering (deluxe edition)

- Kate Dear – packaging coordination (deluxe edition)

- Steve Friedberg – engineering

- David Gahr – photography

- Lisa Glines – art direction and design (deluxe edition)

- Brian Kehew – additional mixing and mastering (deluxe edition)

- Elliot Landy – photography, remastering and liner notes (deluxe edition)

- Alan Light – liner notes

- Tony May – engineering

- Lewis Merenstein – executive production

- Janet Planet – liner notes

- Neil Schwartz – engineering

- Elliot Scheiner – engineering

- Steve Woolard – production (deluxe edition)

- Shelly Yakus – engineering

Charts

edit| Chart (1970–71) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[67] | 20 |

| American Albums Chart[68] | 29 |

| British Albums Chart[68] | 32 |

| Dutch Albums Chart[69] | 9 |

| German Albums Chart[69] | 56 |

| Norwegian Albums Chart[69] | 19 |

| Chart (2013) | Peak position |

| Italian Albums Chart[69] | 42 |

| New Zealander Albums Chart[69] | 36 |

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[70] | Platinum | 300,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[52] | 3× Platinum | 3,000,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Anon. 2007, p. 201; Walsh 2018a, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Anon. 2007, p. 201; Christgau 1972.

- ^ Heylin 2004, p. 229; Anon. 2007, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e f g Walsh 2018b.

- ^ a b c d e Yorke 1975, pp. 70–83.

- ^ Rogan 2006, p. 248.

- ^ Tobler 2005; Hage 2009, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Tobler 2005.

- ^ Heylin 2004, p. 215.

- ^ a b Hage 2009, p. 63.

- ^ a b Buskin 2009.

- ^ Anon. 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Evans 1992, p. 488; Rogan 2006, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d Harrington 2003, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Christgau 1981, p. 265.

- ^ Light 2006; Milward n.d..

- ^ a b c Evans 1992, p. 488.

- ^ Sheffield 2004, p. 560.

- ^ Anon. (g) n.d.

- ^ a b c Ankeny n.d.

- ^ Rogan 2006, p. 250.

- ^ Harrington 2003, p. 86.

- ^ a b Hinton 2003, p. 106.

- ^ Maginnis n.d.

- ^ Hinton 2003, pp. 106–7.

- ^ Collis 1997, p. 118.

- ^ a b Hinton 2003, p. 107.

- ^ Hage 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Hinton 2003, pp. 108–9.

- ^ Hinton 2003, p. 109.

- ^ a b Hinton 2003, p. 110.

- ^ Yorke 1975, p. 83.

- ^ a b Hinton 2003, p. 111.

- ^ Hage 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Mendelsohn & Klinger 2012; Hage 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Christgau 1970.

- ^ a b Yorke 1975, p. 82.

- ^ Hage 2009, pp. 53–4.

- ^ Anon. 1970, p. 52.

- ^ Hage 2009, pp. 53–4; Gambaccini 1978, pp. 83–4.

- ^ a b Hage 2009, p. 49.

- ^ Hage 2009, pp. 49, 53–4.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Strong 2004.

- ^ Hilburn 1986.

- ^ a b Anon. 2013a.

- ^ Rucker 1996.

- ^ Thomas 2010.

- ^ Harrington 2003, p. 86; Tobler 2005.

- ^ Harrington 2003, p. 87; Gibson 2006, p. 220; Walsh 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Elias 2011.

- ^ a b Anon. (f) n.d.

- ^ Anon. 2013b.

- ^ Gambaccini 1978, pp. 83–4.

- ^ Christgau 1979.

- ^ Anon. (g) n.d.; Anon. 1989, p. 50.

- ^ Anon. 2013b; Anon. 2003, p. 113.

- ^ Anon. 2012; Anon. 2020.

- ^ Larkin 2000, p. 68; Tobler 2005; Light 2006.

- ^ Hinckley 2007.

- ^ McGreevy 2009.

- ^ Reiff 2018.

- ^ Anon. (e) n.d.

- ^ Hermes 2013.

- ^ Anon. 2013c.

- ^ a b c Light, Planet & Scheiner 2013.

- ^ Kent 1993, p. 208.

- ^ a b Anon. 2007, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e Anon. (d) n.d.

- ^ Anon. 2023.

Bibliography

edit- Ankeny, Jason (n.d.). "Moondance – Van Morrison". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Anon. (28 February 1970). "Album Reviews". Billboard.

- Anon. (April 1989). "The 25 Greatest Albums of All Time". Spin.

- Anon. (11 December 2003). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone.

- Anon. (2007). The Mojo Collection (4th ed.). Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1847676436.

- Anon. (31 May 2012). "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Anon. (17 June 2013a). "Van Morrison to Release Deluxe Edition of Moondance". Uncut. Archived from the original on 29 November 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Anon. (1 August 2013b). "Van Morrison's 'Moondance' Album Gets Deluxe Edition Treatment". Goldmine. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Anon. (18 July 2013c). "Van Morrison on Moondance reissue: 'I did not endorse this'". Uncut. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Anon. (22 September 2020). "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- Buskin, Richard (May 2009). "Classic Tracks: Van Morrison 'Moondance'". Sound on Sound. Archived from the original on 25 April 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- Anon. (2023). "Moondance". British Phonographic Industry (BPI). Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- Anon. [d] (n.d.). "Van Morrison – Moondance". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on 5 June 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Anon. [e] (n.d.). "Critics Review for Moondance [Deluxe Edition]". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Anon. [f] (n.d.). "Gold & Platinum". Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). If necessary, enter Moondance in the field Search, then click Advanced, then click Format, then select Album, then click SEARCH. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- Anon. [g] (n.d.). "Van Morrison – Moondance User Opinions". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Christgau, Robert (23 April 1970). "Consumer Guide (9)". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- Christgau, Robert (13 August 1972). "Combining, Refining, Their Rock Soars". Newsday. Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Christgau, Robert (17 December 1979). "Decade Personal Best: '70s". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Christgau, Robert (1981). Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0899190251.

- Collis, John (1997). Van Morrison: Inarticulate Speech of the Heart (reprint ed.). Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306808110.

- Elias, Jean-Claude (17 June 2011). "Van Morrison's Undying Moondance Inspires". The Jordan Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Evans, Paul (1992). "Van Morrison". In DeCurtis, Anthony; Henke, James; George-Warren, Holly (eds.). The Rolling Stone Album Guide (3rd ed.). Random House. ISBN 0679737294.

- Gambaccini, Paul (1978). Rock Critic's Choice: The Top 200 Albums. Omnibus. ISBN 0860014940.

- Gibson, David (2006). The Mixing Engineer's Handbook (2nd ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 1598637681.

- Hage, Erik (2009). The Words and Music of Van Morrison. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313358630.

- Harrington, Joe S. (2003). "32. Van Morrison / Moondance". In Hoye, Jacob (ed.). VH-1's 100 Greatest Albums. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0743448766.

- Hermes, Will (18 October 2013). "Van Morrison: Moondance (Deluxe Edition)". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Heylin, Clinton (2004). Can You Feel the Silence?: Van Morrison – A New Biography (reprint ed.). Chicago Review Press. ISBN 1556525427.

- Hilburn, Robert (29 April 1986). "Compact Discs". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Hinckley, David (7 March 2007). "The Top 200 Albums of All Time". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- Hinton, Brian (2003). Celtic Crossroads: The Art of Van Morrison (2nd ed.). Sanctuary Publishing. ISBN 1860745059.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- Larkin, Colin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- Larkin, Colin (2006). Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195313739.

- Light, Alan (13 November 2006). "The All-TIME 100 Albums: Moondance by Van Morrison". Time. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Light, Alan; Planet, Janet; Scheiner, Elliot (22 October 2013). Moondance (deluxe edition booklet). Van Morrison. Warner Bros. Records. R2 536561.

- Maginnis, Tom (n.d.). "And It Stoned Me – Van Morrison". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- McGreevy, Ronan (18 December 2009). "Stellar Van Morrison Offering Tops Best Album List". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Mendelsohn, Jason; Klinger, Eric (17 August 2012). "Counterbalance No. 94: Van Morrison's 'Moondance'". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Milward, John (n.d.). "Van Morrison – Moondance". Amazon. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- Reiff, Corbin (21 April 2018). "The 10 Best Offerings From Record Store Day 2018". Uproxx. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- Rogan, Johnny (2006). Van Morrison: No Surrender (paperback ed.). Vintage Books. ISBN 0099431831.

- Rucker, Leland (1996). "Van Morrison". In Graff, Gary (ed.). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0787610372.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "Van Morrison". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Strong, Martin C. (2004). "Van Morrison". The Great Rock Discography (7th ed.). Canongate U.S. ISBN 1841956155.

- Thomas, Adam (29 May 2010). "Van Morrison – Moondance (Album Review 2)". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Tobler, John (2005). "Van Morrison: Moondance". In Dimery, Robert (ed.). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 1844033929.

- Walsh, Christopher (22 September 2001). "Still in the Mix". Billboard.

- Walsh, Ryan H. (2018a). Astral Weeks: A Secret History of 1968. Penguin Press. ISBN 9780735221345.

- Walsh, Ryan H. (2018b). "Van Morrison: Moondance Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- Yorke, Ritchie (1975). Van Morrison: Into the Music. Charisma Books. ISBN 085947013X.