The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin; Constantine II, King of Scotland; and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is sometimes cited as the point of origin for English national identity: historians such as Michael Livingston argue that "the men who fought and died on that field forged a political map of the future that remains, arguably making the Battle of Brunanburh one of the most significant battles in the long history not just of England, but of the whole of the British Isles."[1]

| Battle of Brunanburh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Viking invasions of England | |||||||

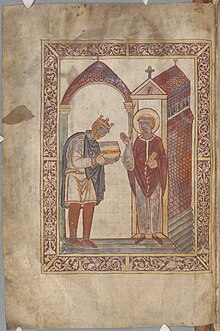

A portrait of Æthelstan presenting a book to Saint Cuthbert | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Kingdom of England |

Kingdom of Dublin Kingdom of Alba Kingdom of Strathclyde | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Æthelstan |

Olaf Guthfrithson Constantine II Owen I | ||||||

Following an unchallenged invasion of Scotland by Æthelstan in 934, possibly launched because Constantine had violated a peace treaty, it became apparent that Æthelstan could be defeated only by an alliance of his enemies. Olaf led Constantine and Owen in the alliance. In August 937 Olaf and his army sailed from Dublin[2] to join forces with Constantine and Owen, but they were routed in the battle against Æthelstan. The poem Battle of Brunanburh in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recounts that there were "never yet as many people killed before this with sword's edge ... since the east Angles and Saxons came up over the broad sea".

Æthelstan's victory preserved the unity of England. The historian Æthelweard wrote around 975 that "[t]he fields of Britain were consolidated into one, there was peace everywhere, and abundance of all things". Alfred Smyth has called the battle "the greatest single battle in Anglo-Saxon history before Hastings". The site of the battle is unknown; many possible locations have been proposed by scholars.

Background

editAfter Æthelstan defeated the Vikings at York in 927, King Constantine of Scotland, King Hywel Dda of Deheubarth, Ealdred I of Bamburgh, and King Owen I of Strathclyde (or Morgan ap Owain of Gwent) accepted Æthelstan's overlordship at Eamont, near Penrith.[3][4][a] Æthelstan became King of England and there was peace until 934.[4]

Æthelstan invaded Scotland with a large military and naval force in 934. Although the reason for this invasion is uncertain, John of Worcester stated that the cause was Constantine's violation of the peace treaty made in 927.[6] Æthelstan evidently travelled through Beverley, Ripon, and Chester-le-Street. The army harassed the Scots up to Kincardineshire and the navy up to Caithness, but Æthelstan's force was never engaged.[7]

Following the invasion of Scotland, it became apparent that Æthelstan could only be defeated by an allied force of his enemies.[7] The leader of the alliance was Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, joined by Constantine II, King of Scotland and Owen, King of Strathclyde.[8] (According to John of Worcester, Constantine was Olaf's father-in-law.)[9] Though they had all been enemies in living memory, historian Michael Livingston points out that "they had agreed to set aside whatever political, cultural, historical, and even religious differences they might have had in order to achieve one common purpose: to destroy Æthelstan".[10]

In August 937, Olaf sailed from Dublin[2] with his army to join forces with Constantine and Owen and in Livingston's opinion this suggests that the battle of Brunanburh occurred in early October of that year.[11] According to Paul Cavill, the invading armies raided Mercia, from which Æthelstan obtained Saxon troops as he travelled north to meet them.[12] Michael Wood wrote that no source mentions any intrusion into Mercia.[13]

Livingston thinks that the invading armies entered England in two waves, Constantine and Owen coming from the north, possibly engaging in some skirmishes with Æthelstan's forces as they followed the Roman road across the Lancashire plains between Carlisle and Manchester, with Olaf's forces joining them on the way. Deakin argues against a western passage for the coalition army by demonstrating that on the few occasions Scottish armies had crossed into England, they had used the Stainmore Pass or Dere Street and were engaged in battle to the east of the Pennines.[14] Livingston speculates that the battle site at Brunanburh was chosen in agreement with Æthelstan, on which "there would be one fight, and to the victor went England".[15]

Battle

editThe battle resulted in an overwhelming victory for Æthelstan's army. The main source of information is the poem "Battle of Brunanburh" in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[8] After travelling north through Mercia, Æthelstan's army met the invading forces at Brunanburh.[16] In a battle that lasted all day, the English finally forced them to break up and flee.[17][18] There was probably a prolonged period of hard fighting before the invaders were finally defeated.[13][18] According to the poem, the English "clove the shield-wall, hacked the war-lime, with hammers's leavings". "There lay many a soldier of the men of the north, shot over shield, taken by spears, likewise Scottish also, sated, weary of war".[19] Wood states that all large battles were described in this manner, so the description in the poem is not unique to Brunanburh.[13]

Æthelstan and his army pursued the invaders until the end of the day, slaying great numbers of enemy troops.[20] Olaf fled and sailed back to Dublin with the remnants of his army and Constantine escaped to Scotland; Owain's fate is not mentioned.[20] According to the poem: "Then the Northmen, bloody survivors of darts, disgraced in spirit, departed on Ding's Mere, in nailed boats over deep water, to seek out Dublin, and their [own] land again." Never has there been greater slaughter "since the Angles and Saxons came here from the east...seized the country".[21]

The Annals of Ulster describe the battle as "great, lamentable and horrible" and record that "several thousands of Norsemen ... fell".[22] Among the casualties were five kings and seven earls from Olaf's army.[18] The poem records that Constantine lost several friends and family members in the battle, including his son.[23] The largest list of those killed in the battle is contained in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, which names several kings and princes.[24] A large number of English also died in the battle,[18] including two of Æthelstan's cousins, Ælfwine and Æthelwine.[25]

Medieval sources

editThe battle of Brunanburh is mentioned or alluded to in over forty Anglo-Saxon, Irish, Welsh, Scottish, Norman and Norse medieval texts.

One of the earliest and most informative sources is the Old English poem "Battle of Brunanburh" in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (version A), which was written within two decades of the battle. The poem relates that Æthelstan and Edmund's army of West Saxons and Mercians fought at Brunanburh against the Vikings under Anlaf (i.e. Olaf Guthfrithson) and the Scots under Constantine. After a fierce battle lasting all day, five young kings, seven of Anlaf's earls, and countless others were killed in the greatest slaughter since the Anglo-Saxon invasions. Anlaf and a small band of men escaped by ship over Dingesmere (or Ding's Mere) to Dublin. Constantine's son was killed, and Constantine fled home.[26]

Another very early source,[27] the Irish Annals of Ulster, calls the battle "a huge war, lamentable and horrible".[28] It notes Anlaf's return to Dublin with a few men the following year, associated with an event in the spring.[13]

In its only entry for 937, the mid/late 10th-century Welsh chronicle Annales Cambriae laconically states "war at Brune".[29]

Æthelweard's Chronicon (ca. 980) says that the battle at "Brunandune" was still known as "the great war" to that day, and no enemy fleet had attacked the country since.[30]

Eadmer of Canterbury's Vita Odonis (very late 11th century) is one of at least six medieval sources to recount Oda of Canterbury's involvement in a miraculous restitution of Æthelstan's sword at the height of the battle.[31]

William Ketel's De Miraculis Sancti Joannis Beverlacensis (early 12th century) relates how, in 937, Æthelstan left his army on his way north to fight the Scots at Brunanburh, and went to visit the tomb of Bishop John at Beverley to ask for his prayers in the forthcoming battle. In thanksgiving for his victory, Æthelstan gave certain privileges and rights to the church at Beverley.[32]

According to Symeon of Durham's Libellus de exordio (1104–15):

- …in the year 937 of the Lord´s Nativity, at Wendune which is called by another name Et Brunnanwerc or Brunnanbyrig, he [Æthelstan] fought against Anlaf, son of former king Guthfrith, who came with 615 ships and had with him the help of the Scots and the Cumbrians.[33]

John of Worcester's Chronicon ex chronicis (early 12th century) was an influential source for later authors and compilers.[34] It corresponds closely to the description of the battle in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but adds that:

- Anlaf, the pagan king of the Irish and many other islands, incited by his father-in-law Constantine, king of the Scots, entered the mouth of the River Humber with a strong fleet.[35]

Another influential work, Gesta regum Anglorum by William of Malmesbury (1127) adds the detail that Æthelstan "purposely held back", letting Anlaf advance "far into England".[36] Michael Wood argues that, in a twelfth-century context, "far into England" could mean anywhere in southern Northumbria or the North Midlands.[13] William of Malmesbury further states that Æthelstan raised 100,000 soldiers. He is at variance with Symeon of Durham in calling Anlaf "son of Sihtric” and asserting that Constantine himself had been slain.[37]

Henry of Huntingdon's Historia Anglorum (1133) adds the detail that Danes living in England had joined Anlaf's army.[38] Michael Wood argues that this, together with a similar remark in the Annals of Clonmacnoise, suggests that Anlaf and his allies had established themselves in a centre of Anglo-Scandinavian power prior to the battle.[13]

The mid-12th century text Estoire des Engleis, by the Anglo-Norman chronicler Geoffrey Gaimar, says that Æthelstan defeated the Scots, men of Cumberland, Welsh and Picts at "Bruneswerce".[39]

The Chronica de Mailros (1173–4) repeats Symeon of Durham's information that Anlaf arrived with 615 ships, but adds that he entered the mouth of the river Humber.[40]

Egil's Saga is an Icelandic saga written in Old Norse in 1220–40, which recounts a battle at "Vínheidi" (Vin-heath) by "Vínuskóga" (Vin-wood); it is generally accepted that this refers to the Battle of Brunanburh.[41] Egil's Saga contains information not found in other sources, such as military engagements prior to the battle, Æthelstan's use of Viking mercenaries, the topology of the battlefield, the position of Anlaf's and Æthelstan's headquarters, and the tactics and unfolding of events during the battle.[42] Historians such as Sarah Foot argue that Egil's Saga may contain elements of truth but is not a historically reliable narrative.[41]

Pseudo-Ingulf's Ingulfi Croylandensis Historia (ca. 1400) recounts that:

the Danes of Northumbria and Norfolk entered into a confederacy [against Æthelstan], which was joined by Constantine, king of the Scots, and many others; on which [Æthelstan] levied an army and led it into Northumbria. On his way, he was met by many pilgrims returning homeward from Beverley… [Æthelstan] offered his poniard upon the holy altar [at Beverley], and made a promise that, if the lord would grant him victory over his enemies, he would redeem the said poniard at a suitable price, which he accordingly did…. In the battle which was fought on this occasion there fell Constantine, king of Scots, and five other kings, twelve earls, and an infinite number of the lower classes, on the side of the barbarians.

— Ingulf 1908, p. 58

The Annals of Clonmacnoise (an early medieval Irish chronicle of unknown date that survives only in an English translation from 1627[43]) states that:

- Awley [i.e. Anlaf], with all the Danes of Dublin and north part of Ireland, departed and went overseas. The Danes that departed from Dublin arrived in England, & by the help of the Danes of that kingdom, they gave battle to the Saxons on the plaines of othlyn, where there was a great slaughter of Normans and Danes.[2]

The Annals of Clonmacnoise records 34,800 Viking and Scottish casualties, including Ceallagh the prince of Scotland (Constantine's son) and nine other named men.[2]

Aftermath

editÆthelstan's victory prevented the dissolution of England, but it failed to unite the island: Scotland and Strathclyde remained independent.[44] Foot writes that "[e]xaggerating the importance of this victory is difficult".[44] Livingston writes that the battle was "the moment when Englishness came of age" and "one of the most significant battles in the long history not just of England but of the whole of the British isles".[45] The battle was called "the greatest single battle in Anglo-Saxon history before the Hastings" by Alfred Smyth, who nonetheless says its consequences beyond Æthelstan's reign have been overstated.[46]

Alex Woolf describes it as a pyrrhic victory for Æthelstan: the campaign against the northern alliance ended in a stalemate, his control of the north declined, and after he died Olaf acceded to the Kingdom of Northumbria without resistance.[47] In 954 however the Norse lost their territory in York and Northumbria, with the death of Eric Bloodaxe.[17]

Æthelstan's ambition to unite the island had failed; the Kingdoms of Scotland and Strathclyde regained their independence, and Great Britain remained divided for centuries to come, Celtic north from Anglo-Saxon south. Æthelweard, writing in the late 900s,[17] said that the battle was "still called the 'great battle' by the common people" and that "[t]he fields of Britain were consolidated into one, there was peace everywhere, and abundance of all things".[48]

Location

editThe location of the battlefield is unknown[18] and has been the subject of lively debate among historians since at least the 17th century.[49] Over forty locations have been proposed, from the southwest of England to Scotland,[50][51] although most historians agree that a location in Northern England is the most plausible.[52][13]

Wirral Archaeology, a local volunteer group, believes that it may have identified the site of the battle near Bromborough on the Wirral.[53] They found a field with a heavy concentration of artifacts which may be a result of metal working in a tenth-century army camp.[54] The location of the field is being kept secret to protect it from nighthawks. As of 2020, they are seeking funds to pursue their research further.[55] The military historian Michael Livingston argues in his 2021 book Never Greater Slaughter that Wirral Archaeology's case for Bromborough is conclusive, but this claim is criticised in a review of the book by Thomas Williams. He accepts that Bromborough is the only surviving place name which originates in Old English Brunanburh, but says that there could have been others. He comments that evidence of military metal working is unsurprising in an area of Viking activity: it is not evidence for a battle, let alone any particular battle.[56] In an article in Notes and Queries in 2022, Michael Deakin questions the philological case for Bromborough as Brunanburh, suggesting that the first element in the name is 'brown' and not 'Bruna'. Bromborough would therefore be 'the brown [stone-built] manor or fort'. The corollary of this argument being the early names of Bromborough cannot be derived from Old English Brunanburh.[57] Michael Wood (historian), in an article in Notes and Queries in 2017, discusses the alternative spelling Brunnanburh 'the burh at the spring or stream', found in several Anglo-Saxon Chronicle manuscripts.[58]

The medieval texts employ a plethora of alternative names for the site of the battle, which historians have attempted to link to known places.[59][60][61] The earliest relevant document is the “Battle of Brunanburh” poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (version A), written within two decades of the battle, which names the battlefield location as “ymbe Brunanburh” (around Brunanburh).[62] Many other medieval sources contain variations on the name Brunanburh, such as Brune,[63][64] Brunandune,[65] Et Brunnanwerc,[33] Bruneford,[66] Cad Dybrunawc[67] Duinbrunde[68] and Brounnyngfelde.[69]

It is thought that the recurring element Brun- could be a personal name, a river name, or the Old English or Old Norse word for a spring or stream.[70][13] Less mystery surrounds the suffixes –burh/–werc, -dun, -ford and –feld, which are the Old English words for a fortification, low hill, ford, and open land respectively.[70]

Not all the place-names contain the Brun- element, however. Symeon of Durham (early 12th C) gives the alternative name Weondune (or Wendune) for the battle site,[33][71] while the Annals of Clonmacnoise say the battle took place on the “plaines of othlyn”[72] Egil's Saga names the locations Vínheiðr and Vínuskóga.[73]

Few medieval texts refer to a known place, although the Humber estuary is mentioned by several sources. John of Worcester's Chronicon (early 12th C),[35] Symeon of Durham's Historia Regum (mid-12th C),[71] the Chronicle of Melrose (late 12th C)[74] and Robert Mannyng of Brunne's Chronicle (1338)[75] all state that Olaf's fleet entered the mouth of the Humber, while Robert of Gloucester's Metrical Chronicle (late 13th C)[76] says the invading army arrived "south of the Humber". Peter of Langtoft's Chronique (ca. 1300)[77] states the armies met at “Bruneburgh on the Humber”, while Robert Mannyng of Brunne's Chronicle (1338)[75] claims the battle was fought at “Brunesburgh on Humber”. Pseudo-Ingulf (ca. 1400)[78] says that as Æthelstan led his army into Northumbria (i.e. north of the Humber) he met on his way many pilgrims coming home from Beverley. Hector Boece's Historia (1527)[79] claims that the battle was fought by the River Ouse, which flows into the Humber estuary.

Few other geographical hints are contained in the medieval sources. The poem in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that the invaders fled over deep water on Dingesmere, perhaps meaning an area of the Irish Sea or an unidentified lake or river.[80] Deakin noted that the term ding had been used in the Old English Andreas (poem) where it is suggested to have been used metaphorically for a grave and/or Hell. His analysis of the context of lines 53–56 of the Brunanburh poem suggest to him that dingesmere is a poetic and figurative term for the sea.[57]

Egil's Saga contains more detailed topographical information than any of the other medieval texts, although its usefulness as historical evidence is disputed.[41] According to this account, Olaf's army occupied an unnamed fortified town north of a heath, with large inhabited areas nearby. Æthelstan's camp was pitched to the south of Olaf, between a river on one side and a forest on raised ground on the other, to the north of another unnamed town at several hours' ride from Olaf's camp.[73]

Many sites have been suggested, including:

- Bromborough on the Wirral[b]

- Barnsdale, South Yorkshire[c]

- Brinsworth, South Yorkshire[d]

- Bromswold[e]

- Burnley[f]

- Burnswark, situated near Lockerbie in southern Scotland[g]

- Lanchester, County Durham[h]

- Hunwick in County Durham[i]

- Londesborough and Nunburnholme, East Riding of Yorkshire[100]

- Heysham, Lancashire[101]

- Barton-upon-Humber in North Lincolnshire[j]

- Little Weighton, East Riding of Yorkshire.[102]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ According to William of Malmesbury it was Owen of Strathclyde who was present at Eamont but the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says Owain of Gwent; it may have been both.[5]

- ^ According to Michael Livingston, the case for a location in the Wirral has wide support among many scholars.[81] Charters from the 1200s suggest that Bromborough (a town on the Wirral Peninsula[82]) was originally named Brunanburh[83] (which could mean "Bruna's fort").[84] In his essay "The Place-Name Debate", Paul Cavill listed the steps by which this transition may have occurred.[85] Evidence suggests that there were Scandinavian settlements in the area starting in the late 800s, and the town is also situated near the River Mersey, which according to Sarah Foot was a commonly used route by Vikings sailing from Ireland.[83] N.J. Higham suggests the Mersey was never a medieval shipping lane of any consequence. He doubts the Viking fleet used the river because of the extensive mosslands which would have hampered disembarkation. ("The Context of Brunanburh" in Rumble, A.R.; A.D. Mills (1997). Names, Places, People. An Onomastic Miscellany in Memory of John McNeal Dodgson. Stamford: Paul Watkins. p153). Additionally, the Chronicle states that the invaders escaped at Dingesmere, and Dingesmere could be interpreted as "mere of the Thing". The word Thing (or þing, in Old Norse) might be a reference to the Viking Thing (or assembly) at Thingwall on the Wirral. In Old English, mere refers to a body of water, although the specific type of body varies depending on the context. In some cases, it refers to a wetland, and a large wetland is present in the area. Therefore, in their article "Revisiting Dingesmere", Cavill, Harding, and Jesch propose that Dingesmere is a reference to a marshland or wetland near the Viking Thing at Thingwall on the Wirral Peninsula.[82] Deakin questions the onomastic process by which Dingesmere is supposed to have been created and also argues that such a wetland on the tenth-century Wirral coast of the Dee was unlikely.[57] Since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes the battle as taking place "ymbe Brunanburh" ("around Brunanburh"), numerous locations near Bromborough have been proposed, including the Brackenwood Golf Course in Bebington, Wirral (formerly within the Bromborough parish).[86] Recent research on the Wirral has identified a possible landing site for the Norse and Scots.[87] This is a feature called Wallasey Pool. This is in the north of the Wirral near the River Mersey. The pool is linked to the river by a creek which, before it was developed into modern docks, stretched inland some two miles, was, at high tide over 20 feet (6 m) deep and was surrounded by a moss or mere which is now known as Bidston Moss. In addition to this landing site an unconfirmed Roman Road is suggested to have led from the area of Bidston to Chester. Following the route of this road would take an invading force through the area the battle is believed to have been fought. Landscape survey[88] has identified a likely position for Bruna's burh. This survey places the burh at Brimstage approximately 11 miles (18 km) from Chester.

- ^ The civil parish of Burghwallis was recorded as "Burg" in the Domesday book, likely because of a Roman fort situated near the place where the Great North Road (Ermine Street) is met by the road from Templeborough. The site is overlooked by a hill called "Barnsdale Bar", past which flows the River Went. Michael Wood has suggested this site, noting the similarity between Went and Symeon of Durham's Wendun.[13]

- ^ Michael Wood suggests Tinsley Wood, near Brinsworth, as a possible site of the battle. He notes that there is a hill nearby, White Hill, and observes that the surrounding landscape is strikingly similar to the description of the battlefield contained in Egil's Saga. There is an ancient Roman temple on White Hill, and Wood states that the name Symeon of Durham used for the place of the battle, Weondun, means "the hill where there had been a pagan Roman sanctuary or temple". According to Wood, Frank Stenton believed that this piece of evidence could help in finding the location of the battle. There is also a Roman fort nearby, and burh means "fortified place" in Old English; Wood suggests that this fort may have been Brunanburh.[89]

- ^ According to Alfred Smyth, the original form of the name Bromswold, Bruneswald, could fit with Brunanburh and other variants of the name.[90]

- ^ In 1856, Burnley Grammar School master and antiquary Thomas T. Wilkinson published a paper suggesting that the battle occurred on the moors above Burnley, noting that the town stands on the River Brun.[91] His work was subsequently referenced and expanded by a number of local authors.[92] Notably Thomas Newbigging argued the battle took place six miles from Burnley, namely in Broadclough, Rossendale, associating the battle with an area known as Broadclough Dykes.[93] Broadclough is also said to be the site where a Danish chieftain was killed in a battle between the Danes and Saxons. His grave is said to be at a farm near Stubbylee.[94]

- ^ [95] Burnswark is a hill 280 metres (920 ft) tall, and is the site of two Roman military camps and many fortifications from the Iron Age. It was initially suggested as the site of the battle by George Neilson in 1899 and was the leading theory in the early 1900s, having obtained support from historians such as Charles Oman. Kevin Halloran argues that the different forms used by various authors when naming the battle site associate it with a hill and fortifications, since burh (used by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle poem) means "a fortified place", and dune (used by Æthelweard and Symeon of Durham, in names such as Brunandune and We(o)ndune) means "a hill". He also states that the name "Burnswark" could be related to Bruneswerce, another alternative name for the battle site used by Symeon of Durham and Geoffrey Gaimar.[96]

- ^ Andrew Breeze has argued for Lanchester, since the Roman fort of Longovicium overlooks the point where the road known as Dere Street crossed the River Browney.[97][98]

- ^ Hunwick in County Durham is suggested by Stefan Bjornsson and Bjorn Verhardsson in their book Brunanburh: Located Through Egil's Saga.[99]

- ^ Barton-upon-Humber in North Lincolnshire is the most recent location, suggested by Deakin 2020, pp. 27–44

Citations

edit- ^ Livingston 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Anonymous. ”Annals of Clonmacnoise". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 152–153

- ^ Higham 1993, p. 190.

- ^ a b Foot 2011, p. 20.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 162, n. 15; Woolf 2007, p. 151; Charles-Edwards 2013, pp. 511–512.

- ^ Foot 2011, pp. 164–165; Woolf 2007, pp. 158–165.

- ^ a b Stenton 2001, p. 342.

- ^ a b Foot 2011, p. 170.

- ^ Cavill 2001, p. 103.

- ^ Livingston 2011, p. 11.

- ^ Livingston 2011, p. 14.

- ^ Cavill 2001, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wood 2013, pp. 138–159.

- ^ "Brunnanburh 'The Burh at the Spring: The Battle of South Humberside".

- ^ Livingston 2011, pp. 15–18.

- ^ Cavill 2001, pp. 101–102; Stenton 2001, p. 343.

- ^ a b c Cavill 2001, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e Stenton 2001, p. 343.

- ^ Swanton 2000, pp. 106–08.

- ^ a b Stenton 2001, p. 343; Cavill 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Swanton 2000, pp. 109–10.

- ^ The Annals of Ulster. CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts. 2000. p. 386. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- ^ Foot 2011, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Livingston 2011, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 183.

- ^ Anonymous. "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Version A)”. In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 40–43.

- ^ Thompson Smith, Scott. "The Latin Tradition". in The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. p. 283

- ^ Anonymous. "Annals of Ulster". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 144–145

- ^ Anonymous. ”Annales Cambriae". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 48–49

- ^ Æthelweard. ”Chronicon". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 48–49

- ^ Eadmer of Canterbury. ”Vita Odonis". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 50–53

- ^ "A brief history".

- ^ a b c Symeon of Durham. ”Libellus de Exordio". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 54–55

- ^ Thompson Smith, Scott. ”The Latin Tradition". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. p. 277

- ^ a b John of Worcester. ”Chronicon". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 56–57

- ^ William of Malmesbury. ”Gesta Regum Anglorum". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 56–61

- ^ William of Malmesbury. "Gesta Regum Anglorum". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 56–61

- ^ Henry of Huntingdon. "Historia Anglorum". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 60–65

- ^ Gaimar, Geoffrey. "Estoire des Engleis". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 64–5

- ^ Anonymous. "Chronica de Mailros". in The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 66–7

- ^ a b c Foot 2011, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Anonymous. "Egils Saga". in The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 69–81

- ^ Foot 2011, p. 165.

- ^ a b Foot 2011, p. 171.

- ^ Livingston, Michael. "The Roads to Brunanburh", in Livingston 2011, p. 1

- ^ Smyth 1975, p. 62; Smyth 1984, p. 204.

- ^ Woolf 2013, "Scotland", p. 256

- ^ "Aethelweard". brunanburh.org.uk. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Parker, Joanne. ”The Victorian Imagination". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 400–401

- ^ Foot 2011, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Hill, Paul. The Age of Athelstan: Britain´s Forgotten History. Tempus. 2004. pp. 141–142

- ^ Foot 2011, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Wirral Archaeology Press Release (22 October 2019). "The search for the Battle of Brunanburh, is over". Liverpool University Press blog.

- ^ Livingston, Michael (2019). "Has the Battle of Brunanburh battlefield been discovered?". medievalists.net.

- ^ Wirral Archaeology (2019). "The Search for the Battle of Brunanburh".

- ^ Williams, Thomas (September–October 2021). "Review of 'Never Greater Slaughter: Brunanburh and the Birth of England'". British Archaeology: 58. ISSN 1357-4442.

- ^ a b c "Bromborough, Brunanburh, and Dingesmere".

- ^ "The Spelling of Brunanburh".

- ^ Hill, Paul. The Age of Athelstan: Britain´s Forgotten History. Tempus. 2004. pp. 139–153

- ^ Foot 2011, pp. 172–179.

- ^ Cavill, Paul. ”The Place-Name Debate". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 327–349

- ^ Anonymous. "Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (Version A)”. In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 40–43

- ^ Anonymous. ”Annales Cambriae". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 48–49

- ^ Anonymous. ”Brenhinedd y Saesson". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 90–91

- ^ Æthelweard. ”Chronicon". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 48–49

- ^ William of Malmesbury. ”Gesta Regum Anglorum". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 56–61

- ^ Gwynfardd Brycheiniog. ”Canu y Dewi". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 66–67

- ^ Anonymous. ”Scottish Chronicle". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 132–133

- ^ Walter Bower. ”Scotichronicon". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 138–139

- ^ a b Cavill, Paul. ”The Place-Name Debate". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 331–335

- ^ a b Symeon of Durham. ”Historia Regum". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 64–65

- ^ Anonymous. ”Annals of Clonmacnoise". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 152–153

- ^ a b Anonymous. ”Egil´s Saga". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 70–71

- ^ Anonymous. ”Chronica de Mailros". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 66–67

- ^ a b Robert Mannyng of Brune. ”Chronicle". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 126–133

- ^ Robert of Gloucester. ”Metrical Chronicle". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 84–89

- ^ Peter of Langtoft. ”Chronique". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 90–97

- ^ Pseudo-Ingulf. ”Ingulfi Croylandensis Historia". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 134–139

- ^ Hector Boece. ”Historiae". In The Battle of Brunanburh. A Casebook. Ed. Michael Livingston. University of Exeter Press. 2011. pp. 146–153

- ^ Swanton 2000, p. 109 n. 8.

- ^ Livingston 2011, p. 19.

- ^ a b Cavill, Paul; Harding, Stephen; Jesch, Judith (October 2004). "Revisiting Dingesmere". Journal of the English Place Name Society. 36: 25–36.

- ^ a b Foot 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Cavill 2001, p. 105.

- ^ Cavill, Paul. "The Place-Name Debate", in Livingston 2011, p. 328

- ^ Birthplace of Englishness 'found'. BBC News Online (URL accessed 27 August 2006).

- ^ Capener, David, Brunanburh and the Routes to Dingesmere, 2014. Countyvise Ltd[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ Capener, David, 2014

- ^ Wood 2001, pp. 206–214.

- ^ Smyth 1975, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Wilkinson 1857, pp. 21–41.

- ^ Partington 1909, pp. 28–43.

- ^ Newbigging 1893, pp. 9–21.

- ^ "History of the Parish of Rochdale" (PDF). The Rochdale Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2019.

- ^ "Battle of Brunanburh". UK Battlefields Trust. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ Halloran 2005, pp. 133–148.

- ^ Breeze, Andrew (4 December 2014). "Brunanburh in 937: Bromborough or Lanchester?". Society of Antiquaries of London: Ordinary Meeting of Fellows. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ Breeze, Andrew (2018). Brunanburh Located: The Battlefield and the Poem in Aspects of Medieval English Language and Literature (ed. Michiko Ogura and Hans Sauer). Peter Lang: Berlin. pp. 61–80. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Björnsson, 2020

- ^ England, Sally (2020). "The Nunburnholme Cross and the Battle of Brunanburh". The Archaeological Forum Journal. 2. Council for British Archaeology: 24–57.

- ^ "Brun and Brunanburh: Burnley and Heysham" (PDF). North West Regional Studies.

- ^ Bulmer's History and Directory of East Yorkshire (1892).

Sources

edit- Björnsson, Stefán (2020). Brunanburh – Located through Egils´saga (3rd ed.). Hugfari.

- Cavill, Paul (2001). Vikings: Fear and Faith in Anglo-Saxon England (PDF). HarperCollins Publishers.

- Charles-Edwards, T. M. (2013). Wales and the Britons 350–1064. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821731-2.

- Clarkson, Tim (2012). The Makers of Scotland: Picts, Romans, Gaels and Vikings. Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-907909-01-6.

- Deakin, Michael (2022). "Bromborough, Brunanburh and Dingesmere". Notes and Queries. 69 (2): 65–71. doi:10.1093/notesj/gjac020.

- Deakin, Michael (2020). "Brunnanburh - The burh at the Spring: The Battle of South Humberside". The East Yorkshire Historian Journal. 21: 27–44. ISSN 1469-980X.[permanent dead link]

- Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ivarr to AD 1014. Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1906716066.

- Foot, Sarah (2011). Æthelstan: The First King of England. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12535-1.

- Higham, N. J. (1993). The Kingdom of Northumbria: AD 350–1100. Alan Sutton. ISBN 978-0-86299-730-4.

- Halloran, Kevin (October 2005). "The Brunanburh Campaign: A Reappraisal" (PDF). The Scottish Historical Review. 84 (218). Edinburgh University Press: 133–148. doi:10.3366/shr.2005.84.2.133. JSTOR 25529849. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Hill, Paul (2004). The Age of Athelstan: Britain's Forgotten History. Tempus Publishing.

- Ingulf (1908). Ingulph's chronicle of the abbey of Croyland with the continuations by Peter of Blois and anonymous writers. Translated by Henry T. Riley. London: H. G. Bohn.

- Livingston, Michael, ed. (2011). The Battle of Brunanburh: A Casebook. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0-85989-863-8.

- Livingston, Michael (2021). Never Greater Slaughter: Brunanburh and the Birth of England. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781472849373.

- Newbigging, Thomas (1893). History of the Forest of Rossendale (2nd ed.). Rossendale Free Press.

- Partington, S. W. (1909). The Danes in Lancashire and Yorkshire. Sherratt & Hughes.

- Smyth, Alfred (1975). Scandinavian York and Dublin. Dublin: Templekieran Press.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1984). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland, AD 80–1000. E. Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-6305-6.

- Stenton, Frank M. (2001). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Swanton, Michael, ed. (2000) [1st edition 1996]. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles (revised paperback ed.). London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-84212-003-3.

- Wilkinson, Thomas T. (1857). Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, Volume 9. Society.

- Wood, Michael (2001). In Search of England: Journeys into the English Past. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23218-1.

- Wood, Michael (2013). "Searching for Brunanburh: The Yorkshire Context of the 'Great War' of 937". Yorkshire Archaeological Journal. 85 (1): 138–159. doi:10.1179/0084427613Z.00000000021. ISSN 0084-4276. S2CID 129167209.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba: 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

Further reading

edit- Breeze, Andrew (1999). "The Battle of Brunanburh and Welsh tradition". Neophilologus. 83 (3): 479–482. doi:10.1023/A:1004398614393. S2CID 151098839.

- Breeze, Andrew (March 2016). "The Battle of Brunanburh and Cambridge, CCC, MS183". Northern History. LIII (1): 138–145. doi:10.1080/0078172x.2016.1127631. S2CID 163455344.

- Campbell, Alistair (17 March 1970). "Skaldic Verse and Anglo-Saxon History" (PDF). Dorothea Coke Memorial Lecture. Viking Society for Northern Research. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- Downham, Clare (2021). "A Wirral Location for the Battle of Brunanburh". Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 170: 15–32. doi:10.3828/transactions.170.5. S2CID 239206076.

- Foot, Sarah, "Where English becomes British: Rethinking Contexts for Brunanburh", in Barrow, Julia; Andrew Wareham (2008). Myth, Rulership, Church and Charters: Essays in Honour of Nicholas Brooks. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 127–144.

- Halloran, Kevin (2005). "The Brunanburh Campaign: A Reappraisal". Scottish Historical Review. 84 (2): 133–148. doi:10.3366/shr.2005.84.2.133. JSTOR 25529849.

- Higham, Nicholas J., "The Context of Brunanburh" in Rumble, A.R.; A.D. Mills (1997). Names, Places, People. An Onomastic Miscellany in Memory of John McNeal Dodgson. Stamford: Paul Watkins. pp. 144–156.

- Niles, J.D. (1987). "Skaldic Technique in Brunanburh". Scandinavian Studies. 59 (3): 356–366. JSTOR 40918870.

- Orton, Peter (1994). "On the Transmission and Phonology of The Battle of Brunanburh" (PDF). Leeds Studies in English. 24: 1–28.

- Wood, Michael (1980). "Brunanburh Revisited". Saga Book of the Viking Society for Northern Research. 20 (3): 200–217.

- Wood, Michael (1999). "Tinsley Wood". In Search of England. London. pp. 203–221. ISBN 9780520225824.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

edit