The Brood is a 1979 Canadian psychological body horror film written and directed by David Cronenberg and starring Oliver Reed, Samantha Eggar, and Art Hindle. Its plot follows a man and his mentally ill ex-wife, who has been sequestered by a psychiatrist known for his controversial therapy techniques. A series of brutal unsolved murders serves as the backdrop for the central narrative.

| The Brood | |

|---|---|

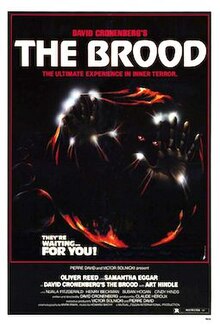

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Cronenberg |

| Written by | David Cronenberg |

| Produced by | Claude Héroux |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Mark Irwin |

| Edited by | Alan Collins |

| Music by | Howard Shore |

Production companies | Les Productions Mutuelles Ltée Elgin International Productions |

| Distributed by | New World Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | CAD$1.4 million |

| Box office | $5 million[1] |

Written by Cronenberg after his own acrimonious divorce, he intended the screenplay as a meditation on a fractured relationship between a husband and wife who share a child, and cast Eggar and Hindle as loose facsimiles of himself and his ex-wife. He would later state that, despite its incorporation of science fiction elements, he considered it his sole feature that most embodied a "classic horror film". Principal photography of The Brood took place in late 1978 in Toronto on a budget of $1.5 million. The film's score was composed by Howard Shore, in his film composing debut.

Released in the spring of 1979 by New World Pictures, The Brood proved profitable for the studio, grossing over $5 million. Though it initially received positive reviews from critics, it would establish itself as a cult film in the following decades. It has attracted scholarly interest from academics in the areas of film theory for its themes regarding mental illness and parenthood. In 2006, the Chicago Film Critics Association named it the 88th scariest film of all time. In 2013, it was selected for restoration by the Criterion Collection, which subsequently released it on Blu-ray.

Plot

editDr. Hal Raglan, a psychotherapist, encourages patients with mental disturbances to let go of their suppressed emotions through physiological changes to their bodies in a technique he calls "psychoplasmics". One of his patients is Nola Carveth, a severely disturbed woman who is legally embattled with her husband Frank for custody of their five-year-old daughter Candice. When Frank discovers bruises and scratches on Candice following a visit with Nola, he informs Raglan of his intent to stop visitation rights. Wanting to protect his patient, Raglan begins to intensify the sessions with Nola to resolve the issue quickly. During the therapy sessions, he discovers that Nola was physically and verbally abused by her alcoholic mother, Juliana, while neglected by her co-dependent alcoholic father, Barton, who refused to protect Nola out of shame and denial.

Frank, intending to invalidate Raglan's methods, questions Jan Hartog, a former patient who is dying of psychoplasmic-induced lymphoma. He leaves Candice with Juliana and the two spend the evening viewing old photographs. Juliana tells Candice that Nola was frequently hospitalized as a child and often exhibited strange unexplained wheals on her skin that doctors were unable to diagnose. While in the kitchen, Juliana is attacked and bludgeoned to death by a small, dwarf-like child. Candice is traumatized, but physically unharmed.

Juliana's ex-husband Barton returns for the funeral and attempts to contact Nola, but Raglan turns him away. Frank invites Candice's teacher, Ruth Mayer, home for dinner to discuss his daughter's performance in school. Barton interrupts with a drunken phone call from Juliana's home, demanding that Frank and he go to Raglan's institute to see Nola. Frank leaves to calm Barton, leaving Candice in Ruth's care. While he's away, Ruth answers a phone call from Nola, who, recognizing her voice and believing her to be having an affair with Frank, insults her and angrily warns Ruth to stay away from her family. Meanwhile, Frank arrives to find Barton murdered by the same deformed dwarf-child, who dies after attempting to kill Frank.

An autopsy of the dwarf-child reveals a multitude of bizarre anatomical anomalies: the creature is asexual, supposedly colorblind, naturally toothless and devoid of a navel, indicating no known means of natural human birth. After the murders catch the attention of newspapers, Raglan reluctantly acknowledges that the deaths coincided with his sessions with Nola relating to their respective topics. He closes his institute and sends his patients to municipal care with the exception of Nola. Frank is alerted about the closure of the institute by Hartog.

Mike Trellan, one of Raglan's other patients, tells Frank that Nola is now Raglan's "queen bee" and in charge of some "disturbed children" in an attic. When Candice returns to school, two dwarf-children attack and kill Ruth in front of her class before absconding with Candice to the institute, with Frank in pursuit. Upon arrival, Raglan tells Frank the truth about the dwarf-children: they are the accidental product of Nola's psychoplasmic sessions; her rage about her abuse was so strong that she parthenogenetically bore a brood of creatures resembling children who psychically respond and act on the targets of her rage, with Nola completely unaware of their actions. Realizing the brood are too dangerous to keep anymore, Raglan plans to venture into their quarters and rescue Candice, provided that Frank can keep Nola calm to avoid provoking the children.

Frank attempts a feigned rapprochement long enough for Raglan to collect Candice, but when he witnesses Nola give birth to another child through a psychoplasmically-induced external womb, she notices his disgust when she licks the child clean. The brood awakens and kills Raglan. Nola then threatens to kill Candice rather than lose her. The brood goes after Candice, who hides in a closet, but they begin to break through the door and try to grab her. In desperation, Frank strangles Nola to death, and the brood dies without its mother's psychic connection. Frank carries a visibly traumatized Candice back to his car and the two depart. As the pair sit in silence, two small lesions—a germinal stage of the phenomenon experienced by Nola—appear on Candice's arm.

Cast

edit- Oliver Reed as Dr. Hal Raglan

- Samantha Eggar as Nola Carveth

- Art Hindle as Frank Carveth

- Henry Beckman as Barton Kelly

- Nuala Fitzgerald as Juliana Kelly

- Susan Hogan as Ruth Mayer

- Cindy Hinds as Candice Carveth

- Gary McKeehan as Mike Trellan

- Michael Magee as Inspector

- Robert A. Silverman as Jan Hartog

- Larry Solway as Lawyer

- Nicholas Campbell as Chris

Production

editScreenplay

edit"The Brood is my version of Kramer vs. Kramer, but more realistic."

In retrospect, Cronenberg stated that he felt The Brood was "the most classic horror film I've done" in terms of structure.[3] He conceived the screenplay in the aftermath of an acrimonious divorce from his wife, which resulted in a bitter custody battle over their daughter.[3][4] During his divorce, Cronenberg became aware of the drama Kramer vs. Kramer (also released in 1979),[a] and was disillusioned by its optimistic depiction of a familial breakdown after a couple's separation.[3] In response, he began writing the screenplay for The Brood, aspiring to depict the strife between a divorced couple battling over their child.[3]

Casting

editIn casting the roles of Frank and Nola Carveth, Cronenberg sought actors who were "vague facsimiles" of himself and his wife.[3][7] Canadian actor Art Hindle was cast in the role of Frank.[8] There was difficulty in casting Nola Carveth and Samantha Eggar, who Cronenberg stated "looked a little like my ex-wife" and had a husband that looked like him, was selected.[9] Cronenberg met Eggar ten years later at the Sitges Film Festival where she told him that "The Brood was the strangest and most repulsive film I've ever done".[10]

Oliver Reed was cast in the role of Hal Raglan, the psychologist who has kept Nola sequestered after her divorce from Frank.[3] He accepted a reduced salary for the role.[11] This marked the second time Eggar and Reed had starred in a film together, having previously co-starred in The Lady in the Car with Glasses and a Gun (1970).[8] Additionally, Eggar and Reed had known one another personally, having grown up together in Bledlow, England.[8] Eggar was impressed by Cronenberg's screenplay, and agreed to appear in the film as she felt the role of Nola was "almost Shakespearean... How could you turn this part down?"[8]

Filming

editLes Productions Mutuelles Ltée and Elgin International Productions produced the film as The Brood Films. The film was shot in Toronto from 14 November to 21 December 1978, on a budget of $1,400,000 (equivalent to $6,009,290 in 2023) with $200,000 coming from the Canadian Film Development Corporation.[12] The Kortright Centre for Conservation, just north of Toronto, was used as the location of the Somafree Institute. Additional photography was done in Mississauga.

Eggar recalled the production crew being very small, with only around seven crew members in total while she was filming her sequences, many of them "academics and PhDs, standing there holding lights".[8] Her scenes were shot over a period of three days.[3] To portray the brood of children, Cronenberg cast a group of child gymnasts from Toronto.[3]

It was the first Cronenberg film to have an original soundtrack. Shore has written the music for most of Cronenberg's subsequent films.[13] This was the first film scored by composer Howard Shore. Shore's work consists in a composition for chamber orchestra strongly reminiscent of the Second Viennese School's Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg and Anton Webern.

Release

editCensorship

editThe Brood had cuts demanded for an R-rating for its theatrical release in the United States. Eggar conceived the idea of licking the new fetuses that her character Nola Carveth has spawned. "I just thought that when cats have their kittens or dogs have puppies (and I think at that time I had about 8 dogs), they lick them as soon as they’re born. Lick, lick, lick, lick, lick…," Eggar said.[14]

However, when the climactic scene was censored, Cronenberg responded: "I had a long and loving close-up of Samantha licking the fetus […] when the censors, those animals, cut it out, the result was that a lot of people thought she was eating her baby. That's much worse than I was suggesting."[15]

Box office

editThe Brood was released as Chromosome 3 in France and La Clinique De La Terreur in Quebec. The film was distributed by New World Pictures and opened in the United States on 25 May 1979, Canada on 1 June, France on 10 October, and the United Kingdom on 13 March 1980. The French dub was released in Montreal on 14 March 1980.[12] After its screenings in Toronto and Chicago, The Brood grossed $685,000 over only a period of ten days between the two cities.[16] By 1981, the film had grossed over $5 million.[1] Cronenberg was able to purchase a home using his earnings from the film.[17]

Critical response

editWhile Variety called it "an extremely well made, if essentially unpleasant shocker",[18] Leonard Maltin reviewed the film in two sentences: "Eggar eats her own afterbirth while midget clones beat grandparents and lovely young schoolteachers to death with mallets. It's a big, wide, wonderful world we live in!" and rated it an outright "BOMB".[19] Roger Ebert called it "a bore" and "disgusting in ways that are not entertaining; as opposed, for example, to the great disgusting moments in Alien or Dawn of the Dead", and even went as far as asking, "Are there really people who want to see reprehensible trash like this?" concluding with "I guess so. It's in its second week."[20] Writing for the Vancouver Sun, Vaughn Palmer lambasted the film, referring to it as "mean, foul and witless... The people who made The Brood do not like people. They do not even appear to like themselves. They just like money."[16] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times praised the film as "well-made" and "expertly acted," but criticized its depictions of violence, stating: "Perhaps Cronenberg means to make an extreme comment upon the irresponsibility of psychiatrists and parents, but The Brood is so totally sickening it's an irresponsible work itself."[21]

On Rotten Tomatoes, The Brood scored 81%.[22]

In Cult Movies, Danny Peary, who openly disapproves of Shivers and Rabid, calls The Brood "Cronenberg's best film" because "we care about the characters", and, although he dislikes the ending, "an hour and a half of absorbing, solid cinema".[23] In his An Introduction to the American Horror Film, critic Robin Wood views The Brood as a reactionary work portraying feminine power as irrational and horrifying, and the dangerous attempts of Oliver Reed's character's psychoanalysis as an analogue to the dangers of trying to undo repression in society.[24]

The Brood was listed #88 on the "Chicago Film Critics Association's 100 Scariest Movies of All-Time".[25] In 2004, one of its sequences was voted #78 among the "100 Scariest Movie Moments" by the Bravo Channel.[26]

Home media

editThe film was released on VHS in 1982,[27] and on DVD in its original uncensored version by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer on August 26, 2003.[28] Anchor Bay Entertainment subsequently released the film on DVD in the United Kingdom 2005.[29]

In mid-2013, the Criterion Collection added The Brood, as well as Scanners, to their selection of films available to Hulu and iTunes customers. The film was subsequently issued on DVD and Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection on October 13, 2015,[30] featuring a new 2K scan of the original film elements.[31]

Related works

editA novelization by Richard Starks was published to coincide with the film's initial release.[32] In 2009, Spyglass Entertainment announced a remake from a script by Cory Goodman, to be directed by Breck Eisner.[33] Eisner left the project in 2010.[34]

Analysis

editCronenberg stated that it was his only film without humor.[2] Child characters rarely appear in his films, with Cronenberg stating that having a child made it unbearable, but child characters are present in The Brood as "it was cathartic, I had to do it, but I have never done it since" according to Cronenberg.[35]

Written in the aftermath of writer-director Cronenberg's divorce from his wife, The Brood has been noted by critics and film scholars for its prominent themes surrounding fears of parenthood, as well as corollary preoccupations with repression and the treatment of mental illness in women.[31][36]

Film theorist Barbara Creed notes that Nola's parthenogenetic births are thematically "used to demonstrate the horrors of unbridled maternal power" in which a woman gives birth to "deformed manifestations of herself".[37] Scholar Sarah Arnold similarly suggests that, despite Nola's apparent representation as a "bad mother" epitomizing "the monstrous feminine", The Brood "does not disseminate such images unproblematically, [and] instead questions these already (culturally and socially) pre-existing notions of the maternal and motherhood... the film fuses the concerns of the woman's film with that of the body horror film."[38]

Feminist critic Carrie Rickey notes that, like many of Cronenberg's films, The Brood has been accused of presenting a misogynistic representation of women.[39] However, Rickey argues against this assertion, writing: "For me, Cronenberg’s gynophobia is a nonissue. It’s blaming the victim. After all, aren’t we talking about movies where male scientists use women as guinea pigs and then are shocked, shocked when the test subjects become monstrous, voracious, etc.? Let me invoke the Jessica Rabbit defense: The women are not bad, they’re just drawn that way. It’s the male scientists who have inadvertently transformed them into men’s worst nightmares."[39]

References

editNotes

edit- ^ Kramer vs. Kramer was released theatrically in December 1979, after the release of The Brood;[5] though Cronenberg stated that he intended The Brood to be his own version of Kramer vs. Kramer,[3] he would not have seen the film as it was still being shot in January 1979,[6] around the same time filming of The Brood took place. He may have been referring to its source novel by Avery Corman.

References

edit- ^ a b "The Dark Mind of David Cronenberg". Vancouver Sun. Vancouver, British Columbia. February 28, 1981. p. 142 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Cronenberg 2006, p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Botting, Josephine (March 17, 2017). "Why I love... The Brood". British Film Institute. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 52.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (December 19, 1979). "East Side Story". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

- ^ "Dustin Hoffman hopes to return to New York Stage". The Decatur Daily Review. Decatur, Illinois. January 2, 1979. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mathijs 2008, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e Eggar, Samantha; David, Pierre; Irwin, Mark; Board, John; Baker, Rick (2015). Birth Pains (Blu-ray documentary short). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 76.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 84.

- ^ "Horror good for you". Ottawa Journal. 1 August 1979. p. 39. Archived from the original on 13 June 2024 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Turner 1987, p. 285.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 99.

- ^ "Collecting Life: An Interview with Actress Samantha Eggar - July 2014". The Terror Trap.

- ^ Chris Rodley (ed.), Cronenberg on Cronenberg, Faber & Faber, 1997.

- ^ a b Palmer, Vaughn (September 1, 1979). "This movie is mean, foul and witless". Vancouver Sun. Vancouver, British Columbia. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Rodley 1997, p. 75.

- ^ Variety, December 31, 1978.

- ^ Leonard Maltin's 2008 Movie Guide, Signet/New American Library, New York 2007.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (June 5, 1979). "The Brood". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (June 8, 1979). "Tumors Beget Dwarves in 'Brood'". Los Angeles Times. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Brood". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved August 5, 2023.

- ^ Danny Peary, Cult Movies, Dell Publishing, New York 1981.

- ^ Robin Wood, An Introduction to the American Horror Film, in: Bill Nichols (ed.), Movies and Methods Volume II, University of California Press, 1985.

- ^ "Scary: Not all on list from horror genre". The Daily Herald. Chicago, Illinois. October 25, 2006. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Greatest Scariest Movie Moments and Scenes". Filmsite.org. AMC Networks. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

- ^ Mathijs 2008, p. 97.

- ^ "The Brood". JoBlo.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

- ^ "The Brood (1979) Releases". AllMovie. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

- ^ Barkan, Jonathan (July 16, 2015). "'The Brood' And 'Mulholland Dr.' Getting Criterion Editions". Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b McKnight, Brent (November 17, 2015). "Cronenberg's 'The Brood' Taps Into Some Fundamental, Primal Terror". PopMatters. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

- ^ Starks, Richard (1979). Rabid. HarperCollins. ISBN 0583128521.

- ^ Zeitchik, Steven (December 15, 2009). "'Creature from the Black Lagoon' emerges". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ^ Goldberg, Matt (August 10, 2010). "Breck Eisner Leaves The Brood and David Fincher Departs Black Hole". Collider. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012.

- ^ Cronenberg 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Creed 2007, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Creed 2007, p. 47.

- ^ Arnold 2013, p. 84.

- ^ a b Rickey, Carrie (October 13, 2015). "The Brood: Separation Trials". The Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019.

Works cited

edit- Arnold, Sarah (2013). Maternal Horror Film: Melodrama and Motherhood. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-01411-5.

- Creed, Barbara (2007) [1993]. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05258-0.

- Cronenberg, David (2006). David Cronenberg: Interviews with Serge Grünberg. Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0859653765.

- Mathijs, Ernest (2008). The Cinema of David Cronenberg: From Baron of Blood to Cultural Hero. Wallflower Press. ISBN 9781905674657.

- Rodley, Chris, ed. (1997). Cronenberg on Cronenberg. Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571191371.

- Turner, D. John, ed. (1987). Canadian Feature Film Index: 1913-1985. Canadian Film Institute. ISBN 0660533642.

External links

edit- The Brood at IMDb

- The Brood at AllMovie

- The Brood at the TCM Movie Database

- The Brood at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Brood: Separation Trials an essay by Carrie Rickey at the Criterion Collection