The Dot and the Line

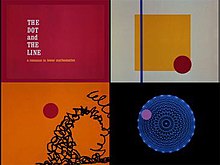

The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics is a 1965 animated short film directed by Chuck Jones and co-directed by Maurice Noble, based on the 1963 book of the same name written and illustrated by Norton Juster, who also provided the film's script. The film was narrated by Robert Morley and produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. It won the 1965 Academy Award for Animated Short Film[2] and was entered into the Short Film Palme d'Or competition at the 1966 Cannes Film Festival.[3]

| The Dot and the Line A Romance in Lower Mathematics | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Chuck Jones Maurice Noble (co-director) |

| Story by | Norton Juster (screenplay) |

| Based on | The Dot and the Line by Norton Juster |

| Produced by | Chuck Jones Les Goldman[1] |

| Narrated by | Robert Morley |

| Music by | Eugene Poddany |

| Animation by | Don Towsley (supervising) Ken Harris Ben Washam Dick Thompson Tom Ray Philip Roman |

| Backgrounds by | Philip DeGuard Don Morgan |

| Color process | Metrocolor |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 10 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Story

editThe story details a straight blue line who is hopelessly in love with a red dot. The dot, finding the line to be stiff, dull, and conventional, turns her affections toward a wild and unkempt squiggle. Taking advantage of the line's stiffness, the squiggle rubs it in that he is a lot more fun for the dot.

The depressed line's friends try to get him to settle down with a female line, but he refuses. He tries to dream of greatness until he finally understands what the squiggle means and decides to be more unconventional. Willing to do whatever it takes to win the dot's affection, the line manages to bend himself and form angle after angle until he is nothing more than a mess of sides, bends, and angles. After he straightens himself out, he settles down and focuses more responsibly on this new ability, creating shapes so complex that he has to label his sides and angles in order to keep his place.

When competing again, the squiggle claims that the line still has nothing to show to the dot. The line proves his rival wrong and is able to show the dot what she is really worth to him. When she sees this, the dot is overwhelmed by the line's responsibility and unconventionality. She then faces the now nervous squiggle, whom she gives a chance to make his case to win her love.

The squiggle makes an effort to reclaim the dot's heart by trying to copy what the line did, but to no avail. No matter how hard he tries to re-shape himself, the squiggle still remains the same tangled, chaotic mess of lines and curves. He tries to tell the dot a joke, but she has realized the flatness of it, and he's forced to retreat. She realizes how much her relationship with the squiggle had been a mistake. What she thought was freedom and joy was nothing more than sloth, chaos, and anarchy.

Fed up, the dot tells the squiggle how she really feels about him, denouncing him as meaningless, undisciplined, insignificant, and out of luck. She leaves with the line, having accepted that he has much more to offer, and the punning moral is presented: "To the vector belong the spoils."[4]

Authorship

editThough listed as being directed by Chuck Jones, the true acting director was Maurice Noble, according to his own recollection—Noble being the long-term background artist and eventually credited as co-director on numerous projects with Jones. Chuck Jones was one of the originators for the adaptation and did the first treatment for the short. However, the results did not please the producers, who then asked Maurice Noble to take over, heavily vexing Jones. Noble recalls the handover happening somewhat dramatically as "Chuck, with a big scowl on his face, came in and threw all the pieces on my big brown bookcase; he stacked the whole picture like this: plunk, plunk, plunk...and stalked out of the room."[5]

Legacy

editThe Dot and the Line served as the inspiration for a collection of jewelry by designer Jane A. Gordon.[6] The short film also inspired The Dot and Line, a blog that publishes essays about cartoons and interviews with voice actors and creators including Genndy Tartakovsky, Andrea Romano, Brandon Vietti, Fred Seibert, and Natalie Palamides.[7]

Availability

editThe cartoon was released as a special feature on The Glass Bottom Boat DVD in 2005.[8] The cartoon is also featured on the 2008 release of Warner Home Video Academy Awards Animation Collection and the 2011 release of the Looney Tunes Platinum Collection: Volume 1 Blu-ray box-set on the third disc as a special feature. In 2005, Robert Xavier Rodriguez made a musical setting of the book for narrator and chamber ensemble with projected images, and in 2011 he made a version for full orchestra.

Notes

edit- This was one of only two non-Tom and Jerry animated short subjects to be released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer after 1958. The other one is The Bear That Wasn't, the final animated short released by MGM.

- "The Dot and the Line" won the final award for an animated short for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and it was Chuck Jones' only award as a producer.[9]

- This was one of two Juster books to be adapted for the big screen by Chuck Jones, although Juster had no involvement with the other, The Phantom Tollbooth.

- Unlike other MGM cartoons from 1963 to 1967, the lion in this film's opening logo is Leo instead of Tanner.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ 1966|Oscars.org

- ^ "The Dot And The Line". Big Cartoon DataBase. 2012-12-16. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: The Dot and the Line". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2009-03-08.

- ^ Internet Archive

- ^ Polson, Tod (2013-08-13). The Noble Approach: Maurice Noble and the Zen of Animation Design. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-1-4521-2738-5.

- ^ "The Dot And The Line at Jane A. Gordon's Facebook page". 2013-04-03.

- ^ "The Dot and Line". The Dot and Line. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ Amazon.com: The Glass Bottom Boat (WS) (DVD)

- ^ Short Film Winners: 1966 Oscars