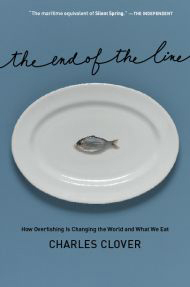

The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat is a book by journalist Charles Clover about overfishing. It was made into a movie released in 2009 and was re-released with updates in 2017.

| |

| Language | English |

|---|---|

| Subject | Fishing, Environment |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Ebury Press (UK) New Press (US) |

Publication date | 2004 (UK)[1] 2006 (US)[1] |

| ISBN | 0-09-189780-7 (UK; Hardcover 1st ed.) ISBN 1-59558-109-X (US; Hardcover 1st ed.) ISBN 0-09-189781-5 (UK; 2005 rev. ed.) ISBN 0-520-25505-4 (US; 2008 reprint, 1st ed.) |

| OCLC | 56083896 |

Clover, a former environment editor of the Daily Telegraph and now a columnist on the Sunday Times, describes how modern fishing is destroying ocean ecosystems. He concludes that current worldwide fish consumption is unsustainable.[2] The book provides details about overfishing in many of the world's critical ocean habitats, such as the New England fishing grounds, west African coastlines, the European North Atlantic fishing grounds, and the ocean around Japan.[3] The book concludes with suggestions on how the nations of the world could engage in sustainable ocean fishing.[3]

Synopsis

editThis article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (February 2023) |

Fishing is occurring at an unsustainable rate. Technological advances, political indecisiveness, and commercial interests in the fishing industry have produced a culture where fish stocks are being exploited beyond their capacity to regenerate. Commercial fish may become extinct within our lifetimes.

Official figures of global fish stocks have been wrong for several years. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reported that the quantity of wild fish caught had increased from 44 million tons in 1950, to 88 million tons in 1990 and 104 million tons in 2000. These figures were official even though the FAO knew they were false, that the catch was actually decreasing. In 1997, the Grand Banks cod fisheries of Newfoundland, Canada, had collapsed. Seventy-five percent of all fisheries were either fully exploited or overfished.

Critically endangered species of fish are still allowed to be fished. For example, the bluefin tuna stock is equivalent to the black rhino. However, it is still being illegally caught and sold. Furthermore, there is even an oversupply problem in the current market as technological innovations have allowed entire schools of bluefin tuna to be caught at the same time. In Spain, the catch of bluefish tuna has exponentially decreased: 5000 million tons in 1999, 2000 million tons in 2000, 900 million tons in 2005.

Developed countries are exploiting the fishing stocks of developing countries. In West Africa, fishing agreements are made with European, US, and Asian fleets because money is needed to build basic infrastructure like schools and hospitals. This comes at the expense of the local fishing industry which operates at a much less industrialised level, even though much of their local economy is sustained by fisheries. Widespread corruption in developing countries allows agreements to be flouted.

The most common technique for modern fishing, trawling, is severely damaging. A fishing vessel at sea, places a weighted net eight inches into the seabed. The vessel then crawls forward, capturing everything indiscriminately in its net. Some of it commercially viable fish, but a considerable amount is "bycatch". Much of the commercially worthless fish is thrown away, with incalculable damage done to the ecosystem. Han Lindeboom compared the damage done to bottom-dwelling animals to other industries and estimates that fishing is a thousand times more damaging than sand and gravel extraction and a million times more damaging than oil or gas exploration.

Technological advances in the fishing industry are comparable to that of modern warfare. Systems of satellite technology such as the Global Positioning System are used near the surface of the water and sonar with advanced echolocation are used under the water. Boats have improved engines, nets, and lines. Computers can plot fish underwater, specify its quantity, and map it with a three-dimensional image.

Deep sea fishing is becoming more accessible with technological advances and more attractive as global fish stocks decline. Most commercial fish come from the shallow seas of the continental shelves or the surface water of the open oceans. Deep sea fishing involves fishing below 1,000 feet. Deep sea regulation inside each country's 200 mile limit is in its infancy, and it is non-existent in many places. One deep sea fish, blue whiting, has a sustainable catch of 1,000,000 tons a year. Norway alone catches 880,000 tons a year.

There is a history of fishery mismanagement ever since the Industrial Revolution. Industrial fishing began during the late 1800s, when steam-powered trawlers operated in Western Europe. Local fisherman noticed that fish populations were being systematically wiped out. Half of the world's fishing fleet was sunk in World War Two and the opportunity to manage fisheries then was lost. Afterwards, scientific and mathematical models were developed to better understand fish. However, these were not taken seriously. For example, maximum sustainable yield, the optimal point between sustainable population size and fishing intensity, is discredited because of the inability to accurately measure fish populations, but it is still the objective of several international fishing conventions.

Newfoundland, Canada, is a prime example of the collapse of a fishery. Europeans settled and fished in Newfoundland for 500 years, after John Cabot arrived there in 1497. Estimates of the spawning stock of cod are 4.4 million tons at the time of Cabot. In 1992, the fishing industry closed because the cod was at the point of extinction. Now, shrimp and snow crabs have settled in the waters. There are also malign economic incentives as Newfoundland fishers work the fisheries for only 12 weeks a year and then collect unemployment insurance for the rest of the year.

The common oceans, parts of the water that are beyond each country's 200-mile limit, are not being managed properly. Stinting is the favoured method of management around those areas, where each vessel catches a limited amount of fish. However, it does not seem to work, as two species of large toothfish around Antarctica have gone extinct. The vessel construction industry is pushing more vessels to fish in those unregulated areas as fish stocks decrease. For example, the Irish domestic pelagic fleet is already 40% larger than EU fleet limits. Yet, new fishing vessels, such as the Atlantic Dawn at over 15,000 tons, are being constructed due to entrenched business and political interests.

Crimes of omission are a cause in overfishing. People turn a blind eye to this situation. Logbooks do not report true catches. And even if vessels are caught, the fines for vessels that overfish are often not enforced. "Black fish" is the name given to illegal catches. According to the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, 50% of hake and 60% of cod is illegal. The observation of independent observers on fishing vessels that operate illegally are not made public without great censorship, for fear of causing offence.

High end restaurants are serving endangered fish as a delicacy for the wealthy. Celebrity chefs maintain those several restaurants and publish numerous cookbooks on serving endangered fish. The example of Nobu is used, one of the most famous restaurants in the world.

Canned tuna is readily available to the general public. However, most canned tuna is fished unsustainably. The first problem is bycatch. Purse seins up to 80 miles long sweep the oceans for tuna, but catch everything else in the area, including sharks, dolphins, and other fish. Second, little is being done to restrict the tuna fleet. Third, the stock is not managed because the carnage occurs mid-ocean.

Even a scientific discussion of extinction is marred by political interests. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization currently warns that 75% of the world's fisheries are fully exploited, overexploited, or significantly depleted. One practical solution to overfishing is maintaining ecological and economic operations in offshore waters, and ecological and cultural operations in inshore waters.

Rights-based systems of are a viable solution to managing fish. Quotas can be bought or sold such that fishers have incentive to save for the future. Furthermore, fisheries have incentive to watch their neighbours, in case their fish stock declines and the value of their quota falls. Iceland currently uses this system and their waters are among the few places in the world where fish is both plentiful and on the increase.

Marine reserves are another viable method of protecting fish. In order for intensive fishing to occur, 50% of the ocean must be protected so that marine life can be sustained. However, marine reserves are not only an environmental solution, they are cultural treasures that can also generate revenue. In the Great Island Marine Reserve of New Zealand, 1370 acres of water are protected. The largest snappers there are eight times larger than those outside the reserve and 14 times more numerous.

Recreational fishing must be better managed along with industrial fishing. The contemporary angler is equipped with technology such as sonar, fish finders, and global positioning systems. As a consequence, they are taking more fish. Although anglers are more cautious than industrial fisherman, the amount of fish they take is growing.

The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) is an agency that gives an independent certification of sustainability to fisheries. It has three stringent criteria: the fishery must not be overfishing, the fishery must maintain the ecosystem of the fish, the fishery must operate in accordance with local, national, and international law. All fish filets served by McDonald's are MSC certified, with more large stores to follow.

Fish farming is the process of growing fish in an artificial environment. The traditional method involves feeding fish waste vegetables, and this is being done in developing countries. Modern fish farming involves feeding processed small wild fish to large carnivorous fish such as salmon, trout, and prawns. However, modern fish farming often relies on fish taken from the water in the developing world to feed the fish being sold in the developing world. Furthermore, fish farms introduce alien species to local environments.

The situation with the fish in the oceans is dire. The problem of overfishing are as follows: the catches of wild fish have peaked and are now in decline, rational fishery management is the exception rather than the rule, the most valuable fish is trawled to the point of extinction, the developed world is stealing from both the developing world and the future generations, and fish farming, the most viable alternative to aquaculture, has serious issues.

Solutions that people can do: fish less today so we can harvest more fish in the future, eat no fish that is wastefully caught, become educated about fish so that we can reject fish caught unsustainably, and favour the most selective, least wasteful fishing methods. Laws that should be implemented in the future: give fisherman tradable rights to fish, create marine reserves, give regional fisheries bodies real power as they are preserving the populations in their local area, and let citizens take ownership of the sea.

Reviews

editUniversity of British Columbia Professor of Fisheries Daniel Pauly, reviewing the book for the Times Higher Education Supplement, praised the book: "It is entertaining, outrageous and a must-read for anyone who cares about the sea and its denizens, or even about our supply of seafood."[4] The British newspaper The Independent called it "persuasive and desperately disturbing," "the maritime equivalent of Silent Spring".[5]

Although widely reviewed in the United Kingdom, the book received little attention in the United States.[2] However, it was featured on the cover of National Geographic.[6]

Film adaptation

editThe book was made into a documentary film of the same name in 2009.[7] The film examines the threatening extinction of the bluefin tuna, caused by increasing demand for sushi; the impact on populations, marine life and climate resulting from an imbalance in marine populations; and the starvation and hunger in coastal populations, caused by the possible extinction of fish in some waters, the possible loss of livelihoods as experienced in Newfoundland and Labrador following the collapse of the cod population, along with the potential remedies. The film was shot over two years at locations in England, Alaska, Senegal, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Nova Scotia, Malta and the Bahamas, following author Charles Clover as he investigates those responsible for the dwindling marine population.

The film features Clover, along with tuna farmer turned whistle blower Roberto Mielgo, top scientists from around the world, indigenous fishermen and fisheries enforcement officials, who predict that seafood could potentially extinct in 2048. Labelled "the biggest problem you've never heard of, The End of the Line illustrates the disastrous effects of overfishing, and rebukes myths of farmed fish as a solution. The film advocates consumer purchases of sustainable seafood, pleads with politicians and fishermen to acknowledge the chilling devastation of overfishing, and for no-take zones in the sea to protect marine life.

Celebrity chef Jamie Oliver and Japanese restaurant chain Nobu have come under criticism for not taking tuna off the menu. The Economist has called The End of the Line "the inconvenient truth about the impact of overfishing on the world's oceans".[citation needed]

The film was directed by Rupert Murray, executive produced by Christopher Hird and Chris Gorell Barnes, produced by George Duffield and Claire Lewis, and narrated by Ted Danson. A French version was narrated by actress Mélanie Laurent and was released in June 2012 by LUG Cinéma.

Sequel

editA follow-up book Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans was released in June 2022.[8]

See also

edit- Environmental effects of fishing

- Blue Marine Foundation, which was founded by the author and filmmakers

References

edit- ^ a b Barnett, Judith B. "Book Review: The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat." Library Journal. 1 December 2006.

- ^ a b Fromartz, Samuel. "The End of the Line." Salon.com June 20, 2007.

- ^ a b "The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat." Science News. 23 December 2006.

- ^ Pauly, Daniel. "Review of 'The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat'." The Times Higher Education Supplement. 22 April 2005.

- ^ Hirst, Christopher; Patterson, Christina; and Tonkin, Boyd. "Paperbacks." The Independent. 25 February 2005.

- ^ Jansen, Bart. "Fishing for Answer to Hard Questions." Maine Sunday Telegram. 25 March 2007.

- ^ Daunt, Tina. "'The End of the Line' Examines the Perils of Overfishing." Los Angeles Times. June 12, 2009; "Underwater Treasures." The Economist. January 22, 2009.

- ^ "'Rewilding the Sea: How to Save Our Oceans' by Charles Clover available to pre-order". Blue Marine Foundation. 26 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.