...And Justice for All is the fourth studio album by American heavy metal band Metallica, released on August 25, 1988, by Elektra Records. It was Metallica's first full length studio (LP) album to feature bassist Jason Newsted, following the death of their previous bassist Cliff Burton in 1986. Burton received posthumous co-writing credit on "To Live Is to Die" as Newsted followed bass lines Burton had recorded prior to his death.[4]

| ...And Justice for All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 25, 1988 | |||

| Recorded | January 28 – May 1, 1988 | |||

| Studio | One on One (Los Angeles) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 65:24 | |||

| Label | Elektra | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Metallica chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Metallica studio album chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from ...And Justice for All | ||||

| ||||

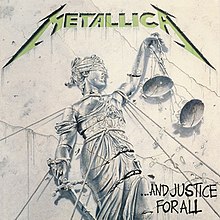

Metallica recorded the album with producer Flemming Rasmussen over four months in early 1988 at One on One Recording Studios in Los Angeles. It features aggressive complexity, fast tempos, and few verse-chorus structures. It contains lyrical themes of political and legal injustices, such as governmental corruption, censorship, and war. The cover, designed by Roger Gorman with illustration by Stephen Gorman and based on a concept by Metallica guitarist James Hetfield and drummer Lars Ulrich, depicts Lady Justice bound in ropes, being pulled by them to the point of breaking, with dollar bills piled upon and falling off her scales. The album title is derived from the last four words of the American Pledge of Allegiance. Three of its songs were released as singles: "Harvester of Sorrow", "Eye of the Beholder", and "One"; the title track, "...And Justice for All", was released as a promotional single.

...And Justice for All was acclaimed by music critics for its depth and complexity, although its dry mix and nearly inaudible bass guitar were criticized. It was included in The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics' poll of the year's best albums, and was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1989, controversially losing out to Jethro Tull in the Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance Vocal or Instrumental category. The single "One" backed the band's debut music video, and earned Metallica their first Grammy Award in 1990 (and the first ever in the Best Metal Performance category). It was successful in the United States, peaking at number six on the Billboard 200, and was certified 8× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in 2003 for shipping eight million copies in the U.S.

The album was reissued on November 2, 2018, in vinyl, CD, and cassette formats, as well as receiving a deluxe box set treatment with bonus tracks and unreleased video footage.[5] The reissue reached number 37 and 42 on Billboard's Top Album Sales and Top Rock Albums charts, respectively.[6][7]

Background

...And Justice for All is the first Metallica album to feature bassist Jason Newsted after the death of Cliff Burton in 1986; Newsted had previously played on the 1987 Metallica EP The $5.98 E.P. - Garage Days Re-Revisited.[8] Metallica had intended to record the album earlier, but was sidetracked by the large number of festival dates scheduled for the summer of 1987, including the European leg of the Monsters of Rock festival. Another reason was frontman James Hetfield's arm injury in a skateboarding accident.[9]

Metallica's previous studio album, Master of Puppets (1986), was their last under their contract with the record label Music for Nations. Manager Peter Mensch wanted them to sign with British record distributor Phonogram Records. Phonogram manager Martin Hooker offered them "well over £1 million, which at that time was the biggest deal we'd ever offered anyone". His explanation was that the final figure for combined British and European sales of all three Metallica albums was more than 1.5 million copies.[9]

Recording

...And Justice for All was recorded from January to May 1988 at One on One Recording Studios in Los Angeles. Metallica produced the album with Flemming Rasmussen.[10] He had been initially unavailable for the planned start on January 1, 1988, and the band hired Mike Clink, who had caught their attention for producing the debut Guns N' Roses album Appetite for Destruction (1987). Plans deteriorated, and Rasmussen became available three weeks after drummer Lars Ulrich had first called him. Rasmussen listened to Clink's rough mixes for the album on his February 14 flight to Los Angeles, and upon his arrival, Clink was fired. Hetfield explained that recording with Clink had been problematic, and Rasmussen was a last-minute replacement.[11] Clink is credited with engineering drums on "The Shortest Straw" and "Harvester of Sorrow". Awaiting Rasmussen's arrival, the band had recorded two cover songs—"Breadfan" and "The Prince"—to "fine‑tune the sound while they got into the studio vibe".[11] Both were released as B-sides for singles from the album and were later included on the 1998 cover album Garage Inc.[12]

Rasmussen's first task was to adjust and arrange the guitar sound, with which the band was dissatisfied. A guide track for the tempos and a click track for Ulrich's drumming were used. The band played in a live room, recording the instruments separately. Each song used three reels: one for drums, a second for bass and guitars, and a third for other parts. Hetfield wrote lyrics during the recording sessions; these were occasionally unfinished as recording began, and Rasmussen said that Hetfield "wasn't really interested in singing" but instead "wanted that hard vibe".[11] Metallica's recording process was new to Newsted, who questioned his impact on the overall sound and the lack of discussion with the rest of the team. He recorded his parts separately, with only the assistant engineer present.[13] The experience differed from his previous band, Flotsam and Jetsam, whose style he described as "basically everybody playing the same thing like a sonic wall".[13]

Mixing

...And Justice for All is noted for its "dry, sterile" production.[14] Rasmussen said that was not his intention, as he tried for an ambient sound similar to the previous two albums. He was not present during the album's mixing, for which Steve Thompson and Michael Barbiero had been hired beforehand. Rasmussen assumed that, in his absence from the mixing process, Thompson and Barbiero used only the close microphones on the mix and none of the room microphones, causing the "clicking", thin drum sound.[11] The bass guitar is nearly inaudible, while the guitars sound "strangled mechanistic".[15] He saw the "synthetic" percussion as another reason for the compressed sound.[16]

At the instruction of Hetfield and Ulrich, Newsted's bass guitar was made almost inaudible.[11][17] According to Rasmussen: "After Lars and James heard their initial mixes the first thing they said was, 'Take the bass down so you can just hear it, and then once you've done that, take it down a further three dBs.' I have no idea why they wanted that, but it was totally out of my hands."[11] In 2009, Hetfield said that the bass was obscured as the basslines often doubled his rhythm guitar, making the instruments indiscernible, and because the low frequencies were competing with his "scooped" guitar sound.[18]

Newsted was not satisfied with the final mix and was unhappy that the bass was inaudible.[11] Thompson was also unhappy, and blamed Ulrich for the decision; he tried to quit the project, but was blocked by management.[17] Rasmussen said in 2018: "I'm probably one of the only people in the world, including Jason and Toby Wright, the assistant engineer, who heard the bass tracks on And Justice for All, and they are fucking brilliant."[19]

In 2019, Hetfield and Ulrich said they had mixed the bass low not to belittle Newsted, but because their hearing was "shot" following heavy touring and so they "basically kept turning everything else up until the bass disappeared".[20] They decided not to adjust the mix for the remastered 2018 reissue, saying: "These records are a product of a certain time in life; they're snapshots of history and they're part of our story ... And Justice for All could use a little more low end and St. Anger could use a little less tin snare drum, but those things are what make those records part of our history."[21]

Music

We took the Ride the Lightning and Master of Puppets concept as far as we could take it. There was no place else to go with the progressive, nutty, sideways side of Metallica, and I'm so proud of the fact that, in some way, that album is kind of the epitome of that progressive side of us up through the '80s.

This is completely sublimated rock, on a quest for a purity of form, light years beyond raunch or blues rock. Metallica turn heavy metal's melodrama into algebra. This isn't thrash, but thresh: mechanized mayhem. There's no blur, no mess, not even at peak velocity, but a rigorous grid of incisions and contusions.

...And Justice for All is a musically progressive album featuring long and complex songs,[24] fast tempos and few verse-chorus structures.[25] Metallica decided to broaden its sonic range, writing songs with multiple sections, heavy guitar arpeggios and unusual time signatures.[26] Hetfield explained: "Songwriting-wise, [the album] was just us really showing off and trying to show what we could do. 'We've jammed six riffs into one song? Let's make it eight. Let's go crazy with it.'"[22]

Critic Simon Reynolds noted the riff changes and experimentation with timing on the album's intricately constructed songs: "The tempo shifts, gear changes, lapses, decelerations and abrupt halts".[23] BBC Music's Eamonn Stack wrote that ...And Justice for All sounds different from the band's previous albums, with longer songs, sparser arrangements, and harsher vocals by Hetfield.[27] According to journalist Martin Popoff, the album is less melodic than its predecessors because of its frequent tempo changes, unusual song structures and layered guitars. He argued that the album is more of a progressive metal record because of its intricately performed music and bleak sound.[28] Music writer Joel McIver called the album's music aggressive enough for Metallica to maintain its place with bands "at the mellower end of extreme metal".[29] According to writer Christopher Knowles, Metallica took "the thrash concept to its logical conclusion" on the album.[30]

Lyrics

The album title was revealed in April 1988: ...And Justice for All, after the final words of the Pledge of Allegiance.[32] The lyrics address political and legal injustice as seen through the prism of war (including nuclear war) and censored speech.[28] The majority of the songs raise issues that differ from the violent retaliation of the previous releases.[33] Tom King writes that for the first time the lyrics dealt with political and environmental issues. He named contemporaries Nuclear Assault as the only other band who applied ecological lyrics to thrash metal songs rather than singing about Satan and Egyptian plagues.[34] McIver noted that Hetfield, the band's main lyricist, wrote about topics that he had not addressed before, such as his revolt against the establishment.[29] Ulrich described the songwriting process as their "CNN years", with him and Hetfield watching the channel in search for song subjects—"I'd read about the blacklisting thing, we'd get a title, 'The Shortest Straw,' and a song would come out of that."[35]

Concerns about the state of the environment ("Blackened"), corruption ("...And Justice for All"), and blacklisting and discrimination ("The Shortest Straw") are emphasized with traditional existential themes.[33] Issues such as freedom of speech and civil liberties ("Eye of the Beholder") are presented from a grim and pessimistic point of view.[36] "One" was unofficially nicknamed an "antiwar anthem" for its lyrics, which portray the suffering of a wounded soldier.[37] "Dyers Eve" is a lyrical rant from Hetfield to his parents.[29] Burton received co-writing credit on "To Live Is to Die" as the bass line is a medley of unused recordings Burton had performed prior to his death. Because the original recordings are not used on the track, the composition is credited as written by Burton and played by Newsted. The spoken word section of the song was erroneously attributed in its entirety to Burton in the liner notes. The first line was actually from the film Excalibur ("When a man lies, he murders some part of the world.")[38] while the second line comes from Lord Foul's Bane, a fantasy novel by American writer Stephen R. Donaldson ("These are the pale deaths which men miscall their lives.").[39][40] The second half of the speech ("All this I cannot bear to witness any longer. Cannot the kingdom of salvation take me home?") was written by Burton.[41]

Artwork

The artwork was created by Stephen Gorman, based on a concept developed by Hetfield and Ulrich. It depicts a cracked statue of a blindfolded Lady Justice, bound by ropes with her breasts exposed and her scales overflowing with dollar bills, with the title in graffiti style.[10]

Critical reception

| Aggregate scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Metacritic | 93/100 (expanded edition)[42] |

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [14] |

| Chicago Tribune | [43] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [44] |

| Metal Forces | 10/10[45] |

| Pitchfork | 9.3/10[46] |

| Q | [47] |

| Rock Hard | 9.5/10[48] |

| Rolling Stone | [25] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [49] |

| The Village Voice | C+[50] |

Released on August 25, 1988,[51] by Elektra Records,[52] ...And Justice for All was acclaimed by music critics.[53] In a contemporary review for Rolling Stone, Michael Azerrad said that Metallica's compositions are impressive and called the album's music "a marvel of precisely channeled aggression".[25] Spin magazine's Sharon Liveten called it a "gem of a double record" and found the music both edgy and technically proficient.[54] Simon Reynolds, writing in Melody Maker, said that "other bands would give their eye teeth" for the songs' riffs and found the album's densely complicated style of metal to be distinct from the monotonous sound of contemporary rock music: "Everything depends on utter punctuality and supreme surgical finesse. It's probably the most incisive music I've ever heard, in the literal sense of the word."[23] Borivoj Krgin of Metal Forces said that it was the most ideal album he has heard because of typically exceptional production and musicianship that is more impressive than that of Master of Puppets.[45] In a less enthusiastic review for The Village Voice, Robert Christgau believed that the band's compositions lack song form and that the album "goes on longer" than Master of Puppets.[50] In 1988, ...And Justice for All was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance, but controversially lost to Jethro Tull's Crest of a Knave.[55] In 2007, Entertainment Weekly, named this one of the 10 biggest upsets in Grammy history.[56]

In a retrospective review, Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune said that ...And Justice for All was both the band's "most ambitious" and ultimately "flattest-sounding" album.[43] AllMusic's Steve Huey noted that Metallica followed the blueprint of the previous two albums, with more sophisticated songs and "apocalyptic" lyrics that envisioned a society in decay.[14] Music journalist Mick Wall was critical of the progressive elements on the album and believed that, apart from "One" and "Dyers Eve", most of the album sounded clumsy.[9] Colin Larkin, writing in the Encyclopedia of Popular Music (2006), noted that, apart from the praiseworthy "One", the album diminished the band's creativity by concentrating the songs with too many riffs.[44] Ulrich said in retrospect that the album has improved with time and it is well-liked among their contemporaries.[22]

Accolades

In The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics poll, it was voted the 39th best album of 1988, having received 117 points within 12 top-ten votes.[57] The album was ranked at number nine on IGN's "Top 25 Metal Albums".[58] Guitar World lists all of its tracks on "The 100 Greatest Metallica Songs of All Time".[59] Kerrang! listed the album at number 42 among the "100 Greatest Heavy Metal Albums of All Time".[60] Martin Popoff ranks it at number 19 in his book The Top 500 Heavy Metal Albums of All Time, the fourth highest ranked Metallica album on the list.[15] It is featured in Robert Dimery's 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[61] In 2017, it was ranked 21st on Rolling Stone's list of "100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time".[62]

After years of refusing to release music videos, Metallica released its first for "One".[63] The video was controversial among fans, who had valued the band's apparent opposition to MTV and other forms of mainstream music. Slant Magazine ranked it number 48 on their list of the "100 Greatest Music Videos", saying that Metallica "evoke a revolution of the soul far more devastating than that presented in the original text".[64] The guitar solo was ranked number seven in Guitar World's compilation of the "100 Greatest Guitar Solos" of all time.[65] Additionally, heavy metal website Noisecreep classed the song ninth among the "10 Best '80s Metal Songs".[66]

Commercial performance

Although Metallica's music was considered unappealing for mainstream radio, ...And Justice for All was highly successful in the US.[67] It became Metallica's best-selling album upon release,[68] peaking at number six on the Billboard 200, where it charted for 83 weeks.[69] More than 9,700,000 copies have been sold in the United States since 1991, when Nielsen SoundScan began tracking sales.[70] It was certified platinum nine weeks after it was released in stores, and 1.7 million copies were sold in the US by the end of 1988.[22][36] Since its release, the album has scanned more than 8 million copies in the US and, according to MTV's Chris Harris, "helped cement [Metallica's] status as a rock and roll force to be reckoned with".[22] Classic Rock explained that with this album, Metallica received substantial media exposure,[31] becoming a multi-platinum act by 1990.[71] The group broke through on radio in early 1989 with "One", which was released as the third single from the record.[72] According to Billboard, the accompanying Damaged Justice tour evolved the band into arena headliners, while significant airplay was garnered by "One" and by the group's first music video.[71]

...And Justice for All achieved similar chart success outside the United States. It topped the charts in Finland, peaked within the top 5 on the charts in Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom, and remained on the UK chart for six weeks.[73][74][75] The album managed to peak in the top 10 on the Norwegian and Swiss album charts.[74] It was less successful in Spain, Mexico, and France, where it peaked at number 92 on the former chart, number 130 on the latter, and number 64 in Spain.[74] ...And Justice for All received a three times platinum certification from Music Canada for shipping 300,000 copies, a platinum certification from IFPI Finland for having a shipment of little over 50,000 copies, and was certified gold by the Bundesverband Musikindustrie (BVMI) for shipments of 250,000 copies.[76][77][78] It was awarded gold by the British Phonographic Industry in 2013 for shipping 100,000 copies in the UK.[79] ...And Justice for All was surpassed commercially by the band's following album, Metallica (1991).[80]

Live performances

Guitarist Kirk Hammett noted that the length of the songs was problematic for fans and for the band: "Touring behind it, we realized that the general consensus was that songs were too fucking long. One day after we played "Justice" and got off the stage one of us said, 'we're never fucking playing that song again.'"[81] Nevertheless, "One" quickly became a permanent fixture in the band's setlist. When performed live, the opening war sound is lengthened from seventeen seconds to approximately two minutes. At the song's conclusion, the stage turns pitch-black and fire erupts from around the stage. The live performance is characterized as a "musical and visual highlight" by Rolling Stone journalist Denise Sheppard.[82] Other songs from ...And Justice for All that have frequently been performed are "Blackened" and "Harvester of Sorrow", which were often featured during the album's promotional Damaged Justice Tour.

Metallica played the title track in the opening show of the Sick of the Studio '07 tour, for the first time since October 1989, and made it a set-fixture for the remainder of that tour. A statue of Lady Justice is commonly placed on the scene, to be torn down as the song approaches its conclusion.[83] In 2009, "The Shortest Straw" returned to the setlist during the World Magnetic Tour after a 12-year absence, and has been sporadically performed since.[84] "Eye of the Beholder" has not been played live since 1989; one such performance appears on Metallica's live extended play Six Feet Down Under.[85] "Dyers Eve" debuted live in 2004, sixteen years after it was recorded, during the Madly in Anger with the World Tour at The Forum in Inglewood, California.[86] "To Live Is to Die" premiered at the band's 30th-anniversary concert in 2011 at The Fillmore in San Francisco.[87] "The Frayed Ends of Sanity", the last song on the album to be performed live, debuted live in Helsinki on the Metallica By Request tour in 2014,[88] although the band had previously played segments during solos, impromptu jams, or in a "Justice" medley.

Track listing

Original release

All lyrics written by James Hetfield, except for the spoken word section of "To Live Is to Die", posthumously attributed to Cliff Burton as it was adapted from four lines Burton authored.[89] The bonus tracks on the digital re-release were recorded live at the Seattle Coliseum, Seattle, Washington on August 29 and 30, 1989, and later appeared on the live album Live Shit: Binge & Purge (1993).

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Blackened" |

| 6:42 |

| 2. | "...And Justice for All" |

| 9:46 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3. | "Eye of the Beholder" |

| 6:25 |

| 4. | "One" |

| 7:26 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5. | "The Shortest Straw" |

| 6:35 |

| 6. | "Harvester of Sorrow" |

| 5:45 |

| 7. | "The Frayed Ends of Sanity" |

| 7:43 |

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8. | "To Live Is to Die" |

| 9:49 |

| 9. | "Dyers Eve" |

| 5:14 |

| Total length: | 65:25 | ||

2018 deluxe box set

In 2018, the album was remastered and reissued in a limited edition deluxe box set with an expanded track listing and bonus content. The deluxe edition set includes the original album on vinyl and CD, three LPs with a remixed and remastered version of the concerts performed at the Seattle Coliseum, Seattle, Washington on August 29 and 30, 1989 (originally included in the box set Live Shit: Binge & Purge), eleven CDs of live tracks, demo recordings, B-sides, rough mixes, and radio edits recorded from 1986 to 1989, and four DVDs of unreleased footage of the band.[90]

Personnel

Credits adapted from the album's liner notes.[10]

|

Metallica

Production

|

Artwork

|

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[102] | Platinum | 60,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[103] | 3× Platinum | 210,000‡ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[76] | 3× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[77] | Platinum | 51,051[77] |

| Germany (BVMI)[104] | 2× Platinum | 1,000,000‡ |

| Italy (FIMI)[105] | Gold | 25,000‡ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[106] | Gold | 7,500^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[107] | Gold | 25,000* |

| Poland (ZPAV)[108] | Platinum | 20,000‡ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[109] | Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[110] | Platinum | 300,000‡ |

| United States (RIAA)[111] | 8× Platinum | 9,700,000[70] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

References

- ^ "Harvester of Sorrow release date". Metallica.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "Eye of the Beholder release date". Metallica.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ "One release date". Metallica.com. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ McIver, Joel (2016). To Live Is to Die: The Life and Death of Metallica's Cliff Burton (2nd ed.). Jawbone Press. pp. (226–227). ISBN 978-1911036128.

- ^ Spencer Kaufman (September 6, 2018). "Metallica announce deluxe reissue of ...And Justice For All". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ^ "Metallica Chart History (Top Album Sales)". Billboard. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ "Metallica Chart History (Top Rock Albums)". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

- ^ J. Bennett. "Metallica "...And Justice for All"". Decibel. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c Wall, Mick (2010). Enter Night: A Biography of Metallica. New York: Orion Publishing Group. pp. 10, 296. ISBN 978-1-4091-1296-9.

- ^ a b c ...And Justice for All liner notes. Vertigo Records. 1988.

- ^ a b c d e f g Buskin, Richard (May 2011). "Metallica 'One': Classic Tracks". Sound on Sound. OCLC 61313197. Archived from the original on May 29, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Metallica: Garage, Inc". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 27, 2014. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Giles, Jeff (May 1, 2013). "Jason Newsted on Inaudible '...And Justice for All' Bass Tracks: 'Water Under the Bridge'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Townsquare Media. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved June 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c Huey, Steve. "Metallica: ...And Justice for All". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Popoff, Martin (2004). The Top 500 Heavy Metal Albums of All Time. Toronto, Canada: ECW Press. pp. Chapter 19. ISBN 978-1-55022-600-3.

- ^ Popoff, Martin (2002). The Top 500 Heavy Metal Songs of All Time. ECW Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-55022-530-3.

- ^ a b Zadrozny, Anya (March 24, 2015). "Sound Mixer on Metallica's '...And Justice For All' Blames Lars Ulrich for Thin Bass Sound". Loudwire. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ Bienstock, Richard (December 2008). "Metallica: Talkin' Thrash". Guitar World. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Grow, Kory (March 17, 2016). "Metallica's 'And Justice for All': What Happened to the Bass?". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "James Hetfield Explains Why Metallica's ...And Justice For All Has No Bass". Kerrang!. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ Scapelliti, Christopher (February 21, 2017). "James Hetfield Tells Why He's Against Fixing the Bass on '...And Justice for All'". guitarworld. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "Metallica Look Back At ... And Justice For All". MTV News. 2008. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ a b c Reynolds, Simon (September 10, 1988). "...And Justice for All". Melody Maker. 64 (37): 36.

- ^ Edmondson, Jacqueline (2013). Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and Stories That Shaped Our Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 708. ISBN 978-0-313-39348-8.

- ^ a b c Azerrad, Michael (November 3, 1988). "And Justice for All by Metallica | Rolling Stone Music". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2011.

- ^ Gulla, Bob (2009). Guitar Gods: The 25 Players who Made Rock History. ABC-CLIO. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-313-35806-7.

- ^ Stack, Eamonn (April 18, 2007). "BBC Review". BBC Music, BBC News. Archived from the original on November 14, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ a b Popoff, Martin (2013). Metallica: The Complete Illustrated History. Voyageur Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7603-4482-8.

- ^ a b c d McIver, Joel (2004). Justice For All – The Truth About Metallica. Music Sales Group. pp. Chapter 16. ISBN 0-85712-009-3.

- ^ Knowles, Christopher (2010). The Secret History of Rock 'n' Roll. Cleis Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-57344-564-1.

- ^ a b "...And Justice for All by Metallica". Classic Rock. July 10, 2013. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- ^ Dome, Malcolm; Wall, Mick, eds. (2011). Metallica: The Music and the Mayhem. Omnibus Press. pp. Chapter 10. ISBN 978-0-85712-721-1.

- ^ a b Irwin, William (2007). Metallica and Philosophy: A Crash Course in Brain Surgery. Pennsylvania: Wiley. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4051-6348-4.

- ^ King, Tom (2011). Metallica – Uncensored On the Record. Great Britain: Coda Books Ltd. pp. Chapter 25. ISBN 978-1-908538-55-0.

- ^ Fricke, David (November 14, 1991). "Metallica: Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 14, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2018.

- ^ a b Brannigan, Paul; Winwood, Ian, eds. (2013). Birth School Metallica Death. Faber & Faber. pp. Chapter 8. ISBN 978-0-571-29416-9.

- ^ Ray, Michael (2013). Disco, Punk, New Wave, Heavy Metal, and More: Music in the 1970s and 1980s. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing. p. 53.

- ^ Irwin, William (2007). Metallica and Philosophy: A Crash Course in Brain Surgery. Pennsylvania: Wiley. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4051-6348-4.

- ^ Donaldson, Stephen R. (1977). Lord Foul's Bane. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-8050-1272-9.

- ^ Barkley, Christine (2009). Stephen R. Donaldson and the Modern Epic Vision. McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7864-4288-1.

- ^ McIver, Joel (2009). To Live Is to Die: The Life and Death of Metallica's Cliff Burton. Jawbone Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-1-906002-24-4.

- ^ "...And Justice for All [30th Anniversary Expanded Edition] by Metallica Reviews and Tracks". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 31, 2021. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (December 1, 1991). "A Guide to Metallica's Recordings". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b Larkin, Colin (2006). Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 5 (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 725. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- ^ a b Krgin, Borivoj (1988). "Metallica – ...And Justice For All". Metal Forces (31). Rockzone Publications Ltd. Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Collins, Sean T. "Metallica – ...And Justice for All". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ "Review: ...And Justice for All". Q (Summer). London: Bauer Media Group: 127. 2001. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ Stratmann, Holger. "...And Justice For All". Rock Hard (in German). Holger Stratmann. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved February 1, 2014.

- ^ Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian David (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. Simon and Schuster. p. 538. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (March 14, 1989). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ^ "…And Justice for All". Metallica. Archived from the original on November 3, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "American album certifications – Metallica – And Justice for All". Recording Industry Association of America. Archived from the original on May 15, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Louie, Tim (May 22, 2013). "Interview with Newsted: Returning With His Own "Metal"". The Aquarian Weekly. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ Liveten, Sharon (November 1988). "Spins". Spin. 4 (8). New York: Spin Media: 97. Retrieved May 9, 2013.

- ^ "Rockin' on an Island". Kerrang! (258). Bauer Media Group. September 30, 1989. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "Grammy's 10 Biggest Upsets". Entertainment Weekly. 2007. Archived from the original on November 8, 2010. Retrieved February 13, 2007.

- ^ "The 1988 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. New York. February 28, 1989. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved January 12, 2014.

- ^ "Top 25 Metal Albums". IGN. January 20, 2007. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Guitar World staff (June 7, 2013). "The 100 Greatest Metallica Songs of All Time". Guitar World. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

- ^ Rhodes, Al (January 21, 1989). "Metallica '...And Justice for All'". Kerrang!. 222. London, UK: Spotlight Publications Ltd.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; McIver, Joel, eds. (2005). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (1st ed.). Universe Publishing. p. 596. ISBN 978-0-7893-1371-3.

- ^ Epstein, Dan (June 21, 2017). "100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ "Metallica – "One"". Rolling Stone. October 28, 2013. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ Cinquemani, Sal (June 30, 2003). "100 Greatest Music Videos (No. 50 to No. 40)". Slant Magazine. London, UK.

- ^ "100 Greatest Guitar Solos". Guitar World. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ Crawford, Allyson B. "10 Best '80s Metal Songs". Noisecreep. Archived from the original on May 24, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2013.

- ^ Klaine, Ted (September–October 1991). "Metal Telepathy". Mother Jones. 16 (5). Foundation For National Progress: 18. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Hart, Josh. "Metallica's '...And Justice For All' to Be Made Available on Green Vinyl". Guitar World. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "Metallica – Chart history". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 11, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2013.

- ^ a b Young, Simon (March 9, 2023). "Here are the astonishing US sales stats for every Metallica album". Metal Hammer. Archived from the original on March 11, 2023. Retrieved March 12, 2023.

- ^ a b Moses, Michael; Kaye, Don (June 5, 1999). "What Did You Do In The War, Daddy?". Billboard. Vol. 111, no. 23. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Campbell, Michael (2008). Popular Music in America: And The Beat Goes On: And the Beat Goes on. Boston: Clark Baxter. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-495-50530-3.

- ^ a b "Finnish Album Charts" (in Finnish). Timo Pennanen. Archived from the original on April 21, 2019. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Metallica – ...And Justice for All" (in German). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "Metallica | full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ a b "Canadian album certifications – Metallica – ...And Justice for All". Music Canada. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Metallica" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Metallica; 'And Justice for All')". Bundesverband Musikindustrie. In the Interpret field, insert Metallica. Archived from the original on December 2, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

- ^ "British album certifications – Metallica – And Justice for All". British Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2014.

- ^ Farr, Jory (1994). Moguls and Madmen: The Pursuit of Power in Popular Music. Simon & Schuster. p. 257. ISBN 0-671-73946-8.

- ^ Fricke, David (November 14, 1991). "Metallica: From Metal to Main Street". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 16, 2015. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Sheppard, Denise (August 28, 2012). "Metallica Bring 'The Full Arsenal' 3D Show to Vancouver". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 15, 2017. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Florino, Rick (November 7, 2013). "Exclusive: James Hetfield of Metallica Reflects on "...And Justice for All"". Artistdirect. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2014.

- ^ Hart, Josh (June 18, 2012). "Video: Metallica Perform "The Shortest Straw" in Helsinki, Finland". Guitar World. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Bosso, Joe (September 9, 2010). "Metallica to release The Six Feet Down Under EP". MusicRadar. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Prato, Greg (June 13, 2012). "Dyers Eve". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 20, 2014. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Fricke, David (December 8, 2011). "Metallica's Star-Studded 30th Anniversary Residency Includes Rarities, Curve Balls". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 27, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2013.

- ^ Grow, Kory (May 29, 2014). "Metallica Give Fan Favorite 'Frayed Ends' a Live Debut, 26 Years Later". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 4, 2014. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ^ McIver, Joel (2009). To Live is to Die: The Life and Death of Metallica's Cliff Burton. Jawbone Press. p. 227. ISBN 9781906002244.

- ^ "...And Justice for All (Remastered) - Deluxe Box Set". Metallica.com. Metallica, Blackened Recordings. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- ^ "RPM Top 100 Albums". RPM. October 15, 1988. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ "Offizielle Deutsche Charts – Offizielle Deutsche Charts". offiziellecharts.de. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018. Retrieved November 9, 2018.

- ^ "Top 40 album-, DVD- és válogatáslemez-lista 2018. 45. hét". Mahasz. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ "Discography Metallica". Hung Medien. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ "メタル・ジャスティス | メタリカ" [...And Justice For All | Metallica]. Oricon. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ "Oficjalna lista sprzedaży :: OLiS - Official Retail Sales Chart". OLiS. Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Salaverri, Fernando (September 2005). Sólo éxitos: año a año, 1959–2002 (1st ed.). Spain: Fundación Autor-SGAE. ISBN 84-8048-639-2.

- ^ "The ARIA Australian Top 100 Albums 1994". Australian Record Industry Association Ltd. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2022.

- ^ "Top 100 Metal Albums of 2002". Jam!. Archived from the original on August 12, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Najpopularniejsze single radiowe i najlepiej sprzedające się płyty 2020 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "sanah podbija sprzedaż fizyczną w Polsce" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2024 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved March 8, 2024.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Metallica; 'And Justice for All')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Metallica – And Justice for All" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ "New Zealand album certifications – Metallica – Justice for All". Recorded Music NZ. September 27, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2024.

- ^ "IFPI Norsk platebransje Trofeer 1993–2011" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Platynowe płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 2021 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry. Retrieved February 24, 2021.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Justice for All')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "British album certifications – Metallica – And Justice for All". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved March 1, 2024.

- ^ "American album certifications – Metallica – And Justice for All". Recording Industry Association of America.

External links

- ...And Justice for All at Discogs (list of releases)