The Honnō-ji Incident (本能寺の変, Honnō-ji no Hen) was the assassination of Japanese daimyo Oda Nobunaga at Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto on 21 June 1582 (2nd day of the sixth month, Tenshō 10). Nobunaga was on the verge of unifying the country, but died in the unexpected rebellion of his vassal Akechi Mitsuhide.[2][3][4]

| Honnō-ji Incident | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Sengoku period | |||||||

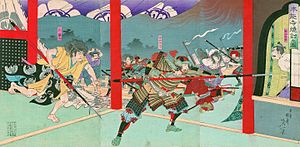

Incident at Honnō-ji, Meiji-era print | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Oda forces under Akechi Mitsuhide's command | Inhabitants and garrison of Honnō-ji, courtiers, merchants, artists, and servants of Oda Nobunaga | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13,000 | 70[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown, presumably minimal | Oda Nobunaga, Mori Ranmaru, Oda Nobutada, and many others | ||||||

Nobunaga only had a few guards and retainers with him when he was attacked, ending his Sengoku period campaign to unify Japan under his power.[2][5] Nobunaga's death was avenged two weeks later when his retainer Toyotomi Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide in the Battle of Yamazaki, paving the way for Hideyoshi to complete the unification of Japan.

Mitsuhide's motive for assassinating Nobunaga is unknown, though there are multiple theories for his betrayal.

Background

editBy 1582, Oda Nobunaga was the most powerful daimyo in Japan and was continuing a sustained campaign of unification in the face of the ongoing political upheaval that characterized Japanese history during the Sengoku period. Nobunaga had destroyed the Takeda clan earlier that year at the Battle of Tenmokuzan and had central Japan firmly under his control, with his only rivals, the Mōri clan and the Uesugi clan, both weakened by internal affairs. The death of Uesugi Kenshin left the Uesugi clan devastated also by an internal conflict between his two adopted sons, weaker than before. The nearly decade-long Ishiyama Hongan-ji War also had already ended with the conclusion of peace.[6] The Mori clan was also in a situation where defeat was almost inevitable and had presented a peace proposal to Hashiba Hideyoshi, offering the cession of five provinces.[7]

It was at this point that Nobunaga began sending his generals aggressively in all directions to continue his military expansion. Nobunaga ordered Hashiba Hideyoshi to attack the Mōri clan in the Chūgoku region; Niwa Nagahide to prepare for an invasion of Shikoku; Takigawa Kazumasu to watch the Hōjō clan from Kōzuke Province and Shinano Province; and Shibata Katsuie to invade Echigo Province, the home domain of the Uesugi clan.[6]

Nobunaga, confident of unifying the country after destroying the Takeda clan, returned to Azuchi in high spirits. Tokugawa Ieyasu also came to Azuchi Castle to thank Nobunaga for giving him the Suruga province. However, around this time, the Mōri clan launched a large-scale counteroffensive in the Chūgoku region, and Nobunaga received a request for reinforcements from Hashiba Hideyoshi, whose forces were stuck besieging the Mōri-controlled Takamatsu Castle.[2]

Nobunaga immediately ordered Akechi Mitsuhide to go to the Chugoku region to support Hideyoshi, and he himself was to follow soon after.[6] Nobunaga began his preparations and headed for Honnō-ji temple in Kyoto, his usual resting place when he stopped by in the capital.[2]

Nobunaga was unprotected at Honnō-ji, deep within his territory, with the only people he had around him being court officials, merchants, upper-class artists, and dozens of servants. Having dispatched most of his soldiers to take part in various campaigns, only a small force was left to protect his person and there was little fear that anyone would dare strike Nobunaga; security measures were weak. Taking advantage of this opening, Mitsuhide suddenly turned against his master.[2]

Mitsuhide's betrayal

editUpon receiving the order, Mitsuhide returned to Sakamoto Castle and moved to his base in Tanba Province. He engaged in a session of renga with several prominent poets, using the opportunity to make clear his intentions of rising against Nobunaga. Mitsuhide saw an opportunity to act, when Nobunaga was not only resting in Honnō-ji and unprepared for an attack, but all the other major daimyō and the bulk of Nobunaga's army were occupied in other parts of the country. Mitsuhide led his army toward Kyoto under the pretense of following the order of Nobunaga. It was not the first time that Nobunaga had demonstrated his modernized and well-equipped troops in Kyoto, so the march toward Kyoto did not raise any suspicion from Mitsuhide's men. Before dawn, Mitsuhide, leading 13,000 soldiers, suddenly changed course in the middle of his march and attacked Honnō-ji Temple, where Nobunaga was staying.[2][6]

There's a legend that when crossing the Katsura River, Mitsuhide announced to his troops that "The enemy awaits at Honnō-ji!" (敵は本能寺にあり, Teki wa Honnō-ji ni ari). However, this story appeared first in Oda Nobunaga-fu (織田信長譜) by Hayashi Razan (1583 – 1657)[8] then in Nihon Gaishi by Rai San'yō, a kangakusha of the late Edo period, and is most likely a creation, not a statement by Akechi himself.[9][10] According to Luís Fróis's "History of Japan" and testimonies from surviving soldiers, Mitsuhide was only the commander of the Oda Army's area forces, and since it was the Oda clan to whom the soldiers owed allegiance, Mitsuhide did not reveal his purpose to anyone except his officers, fearing that informants might appear. Even when the attack actually began, the soldiers did not know whom they were attacking, and some thought it was Ieyasu.[citation needed]

Chronology of the incident

editThe situation at the time was recorded by Gyū-ichi Ota, the author of "Shinchō Kōki", who interviewed the ladies-in-waiting who were at the scene soon after the incident.[11]

Nobunaga had come to Kyoto to support Hashiba Hideyoshi and stayed at Honnō-ji on this day. This was because Nobunaga had not dared to build a castle in Kyoto in order to maintain a distance from the Imperial Court.[4] Moreover, Nobunaga had ordered his generals to go into battle, so only about 150 men were escorting him at Honnō-ji. Akechi Mitsuhide, on the other hand, was leading 13,000 fully armed soldiers. This was a perfect opportunity for Mitsuhide.[2][4] Honnō-ji was a fortified temple with stone walls and a moat, and it had a reasonable defense capability, but it was helpless when surrounded by a large army.[2][4]

On that day, Kyoto seemed to be in the midst of bad weather due to the combination of abnormal weather and the rainy season. The attack began early in the morning. Mitsuhide's forces finished encircling Honnō-ji around 6:00 a.m. and began to invade the temple from all sides.[2][4]

According to Shinchō Kōki, Nobunaga and the pages at first thought that someone had started a fight in the street. But when the enemy raised a battle cry and started shooting, they realized it was a rebellion. Nobunaga asked, "Whose scheme is this?", Mori Ranmaru replied, "It appears to be Akechi's". Nobunaga did not ask back, but simply said, "There is no need to discuss the pros and cons./There is no choice." (是非に及ばず, Zehi ni oyobazu), and began to fight back with bows and arrows at the edge of the palace. When the bowstring broke, he kept shooting arrows while changing bows, and when he ran out of spare bows, he fought with his spear. When Nobunaga was eventually unable to fight after being hit in the elbow by an enemy spear, he retreated and told the nyōbō-shū[a] there, "I don't care, you ladies hurry up and get out of here".[12][13] It was said that Nobunaga then entered the back room of the palace, closed the door of the storage room, and committed seppuku in the burning temple.[2][6][13] The Akechi forces lifted the siege around 8:00 a.m.[4]

Meanwhile, Oda Nobutada, who was at Myōkaku-ji Temple, received news of Mitsuhide's rebellion and attempted to go to Honnō-ji Temple to rescue his father. However, just as he was leaving the temple, Murai Sadakatsu and his sons rushed in and stopped him. Murai said that Honnō-ji had already burned down and the enemy would soon attack us, and advised Nobutada to hunker down in the fortified Nijō Gosho. Upon entering the Nijō Gosho, Nobutada orders Maeda Geni to flee with his infant son, Sanpōshi (Oda Hidenobu), going from Gifu Castle in Mino to Kiyosu Castle in Owari. Nobutada had all the people escape, including the kugyō and the nyōbō-shū,[a] and then he began his war council. Some advised Nobutada to escape and head for Azuchi, but he said, "An enemy who has committed such a rebellion will not let us escape so easily. It would be a disgrace for me to be killed by common soldiers while fleeing", and decided to stay in Kyoto and fight. In the meantime, Akechi completed the siege of Nijō Gosho, making it impossible to escape. Later, Nobutada also committed seppuku.[5]: 69 [6][4] Kamata Shinsuke, who assisted Nobutada in his suicide, hid his head and body according to his instructions.[citation needed]

Aftermath

editAkechi Mitsuhide was eager to find Nobunaga's body in the burnt ruins of Honnō-ji, but he was unable to locate it. Nobunaga's body not being found meant that no one knew if he was alive or dead and created a problem for Mitsuhide. If, by any chance, Nobunaga was alive, the probability of Mitsuhide's defeat increased, and even if it remained unclear whether he is alive or dead, Mitsuhide would find it very difficult to gain support from those who feared Nobunaga's retaliation. In fact, Hideyoshi sent a letter to Nobunaga's vassals that falsely claimed that Nobunaga was still alive to request their cooperation in defeating Mitsuhide. If Mitsuhide had obtained Nobunaga's head, he could have made his death known to the public, and some forces might have followed him. If that had happened, he might have been able to defeat Hideyoshi.[3][4] Meanwhile, Mitsuhide also tried to persuade Oda vassals in the vicinity of Kyoto to recognize his authority after the death of Nobunaga. Then, Mitsuhide entered Nobunaga's Azuchi Castle east of Kyoto and began sending messages to the Imperial Court to boost his position and force the court to recognize his authority as well. However, no one responded to Mitsuhide's call.[citation needed]

Hashiba Hideyoshi received the first news the day after the incident. Hideyoshi immediately made peace with the Mōri clan, kept Nobunaga's death under wraps, and returned to the Kinai region with an ultra-fast, forced march known as Chūgoku Ōgaeshi (the Great Return from the Chugoku Region). After returning in about a week with an army of nearly 30,000 troops for a total distance of 200 km, Hideyoshi joined forces with Niwa Nagahide and Oda Nobutaka in Osaka and headed for Kyoto. With this momentum, Hideyoshi defeated Mitsuhide in the Battle of Yamazaki. While on the run, Mitsuhide was killed as a victim of an ochimushagari.[b][14]

The Kiyosu Conference was then held to determine the successor to the Oda clan, and four vassals of the Oda clan, Shibata Katsuie, Niwa Nagahide, Ikeda Tsuneoki, and Hashiba Hideyoshi, attended the conference. Three names were mentioned as possible successors: Nobukatsu, the second son; Nobutaka, the third son; and Hidenobu (Sanhōshi), Nobutada's eldest son, or Nobunaga's grandson, who was only three years old.[15]

Nobunaga's corpse

editAfter defeating Mitsuhide, Hideyoshi also searched for Nobunaga's body, but it still could not be found. In October 1582, Hideyoshi held Nobunaga's funeral at Daitoku-ji Temple in Kyoto. In place of his missing body, Hideyoshi had a life-size wooden statue of Nobunaga cremated and put it in an urn in place of his ashes.[4]

There is no doubt that what Nobunaga feared most when he prepared to die was not dying but what would happen after death: in other words, how his body would be treated. Nobunaga must have understood that if his body had fallen into Mitsuhide's hands, his severed head would surely have been gibbeted, and he would have been disgraced as a criminal and that Mitsuhide would use Nobunaga's death to justify his rebellion by making it public. In such a situation, Nobunaga had a few possible options. He would have the body burned so that it could not be identified as Nobunaga's, or he would have it buried so that Mitsuhide could not find it inside Honnō-ji, or he would have someone he trusted carry it out of Honnō-ji, even at the risk of being stolen by Mitsuhide on the way.[4] There are several theories regarding the fact that no bodies were found in the burnt ruins of Honnō-ji. One theory is that Nobunaga could not be identified because the bodies were too badly damaged, another that there were too many burned bodies to identify, and a third that the fire was so intense that his body was completely consumed.[c][4]

There are also several stories that Nobunaga's body and head were carried out from Honnō-ji. There are a number of tombs in various parts of Japan that are said to be Nobunaga's, but there is no evidence that his body or ashes are buried in any of them.[4]

Tokugawa escape to Mikawa

editThis section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Grammar and language. (May 2024) |

Tokugawa Ieyasu heard the news in Hirakata, Osaka, but at the time, he had only few companions with him. The Iga province track were also in danger of the Ochimusha-gari, or "Samurai hunters" gang. During the Sengoku period, particularly dangerous groups called "Ochimusha-gari" or "fallen warrior hunter" groups has emerged. These groups consisted of peasant or Rōnin Who dispossessed by war and now formed self-defense forces. However, reality they often resorted to hunt and robbing defeated Samurais or soldiers during conflicts.[16][17][18] These outlaw groups were particularly rampant on the route which Ieyasu taken to return to Mikawa.[18]

Ieyasu and his party, therefore, chose the shortest route back to the Mikawa Province by crossing the Iga Province, which was differed in many versions according to primary sources such as the records of Tokugawa Nikki or Mikawa Todai-Hon:

- The Tokugawa Nikki theory stated that Ieyasu taking the roads to Shijonawate and Son'enji, then following the stream of Kizu river until they spent a night in Yamaguchi castle. The next day they reached a stronghold of Kōka ikki clan of Tarao who allowing them to take refugee for night. Then in the last day, Ieyasu group using a ship from Shiroko to reach Okazaki Castle.[19] However, The Tokugawa Nikki theory were doubted by modern historians, since it was not the shortest route for Ieyasu to reach Mikawa from his starting position at Sakai,[20] while on the other hand, it was also considered by history researchers as very risky path due to the existence of Iga ikki groups which were hostile to Oda and Tokugawa clan.[21][22]

- The Mikawa Toda-Hon stated that Ieyasu went north from Ogawadate, crossed Koka, and entered Seishu Seki (from Shigaraki, passed through Aburahi and entered Tsuge in Iga.[22] This theory was supported by Modern Japanese historian such as Tatsuo Fujita from Mie University, who take this material to formulate three different theories about the details of Ieyasu's trek that he propagated.[23][22] This theory also supported by a group or history researchers of Mie city, which happened to be the descendants of Kōka ikki clans. They stated that by taking this path, before Ieyasu group reached Kada pass where they could be escorted by the Kōka clan Jizamurai, Ieyasu mostly depended his protection on his high-rank vassals, particularly the four Shitennō (Tokugawa clan) generals of Tokugawa clan, rather than the popular theory about the help of "Iga Ninja" clans.[21] In 2023, during the conference of "International Ninja Society" at Chubu Centrair International Airport, a passionate debate occurred which involved Chris Glenn, a DJ and Japanese history enthusiast and author, Uejima Hidetomo, an author history book from Nara, Watanabe Toshitsune, former chairman of the Koga Ninjutsu Research Society, and Sakae Okamoto, mayor of Iga city. In this conference, Toshitsune challenged the common theory about the Iga route which stated by Hidetomo and propagated the theory about Ieyasu taking Kōka route which he viewed more plausible.[24]

Regardless which theory was true, historians agreed that the track ended Kada(a mountain pass between Kameyama town and Iga), Tokugawa group suffered a last attack by the Ochimusha-gari outlaws at Kada pass where they reached the territory of Kōka ikki clans of Jizamurai which are friendly to the Tokugawa clan. The Koka ikki Jizamurai assisted Ieyasu in eliminating the threats of Ochimusha-gari outlaws and escorting them until they reached Iga Province, where they further protected by other friendly group of Iga ikki which accompany the Ieyasu group until they safely reach Mikawa.[18] There are 34 recorded Tokugawa vassals who survived this journey, such as Sakai Tadatsugu, Ii Naomasa, and Honda Tadakatsu, Sakakibara Yasumasa and many others.[17] Other than those four Shitennō generals Matsudaira Ietada recorded in his journal, Ietada nikki (家忠日記), the escorts of Ieyasu during the journey in Iga consisted:[25]

- Ishikawa Kazumasa

- Honda Masamori

- Ishikawa Yasumichi

- Hattori Masanari

- Hiromasa Takagi

- Torii Tadamasa

- Suganuma Sadamitsu

- Hisano shūchō

- Honda Nobutoshi

- Abe Masakatsu

- Makino Yasunari

- Miyake Masatsugu

- Kōriki Kiyonaga

- Ōkubo Tadasuke

- Watanabe Moritsuna

- Naruse Masatora

- Tada Miyoshi

- Hanai Yoshitaka

- Torii Omatsu

- Naitō Shingorō

- Tsudzuki Kamezō

- Matsudaira Harushige

- Suganuma Sadatoshi

- Nagai Naokatsu

- Nagata Sebei

- Matsushita mitsutsuna

- Tsuzuki Chozaburo

- Miura Okame

- Aoki Chōzaburō

- Ōkubo Tadachika

Ietada Nikki also recorded that the escorts of Ieyasu has suffered around 200 casualties during their journey.[26][27]

However, not all of the escaping party manage to escape alive. Anayama Nobutada, a former Twenty-Four Generals of Takeda Shingen member who now an ally to Tokugawa and Nobunaga clan, were ambushed by the Ochimusha-gari during the journey, and killed along with some of his retainers.[18]

Iga Ninja theory's controversy

editIt was reported by Edo period traditional records that Hattori Hanzō, a Tokugawa vassal from Iga, negotiated with Iga ninjas to hire them as guards along the way to avoid the ochimusha-gari.[b] The local Koka-Ikki ninjas and Iga-Ikki ninjas under Hanzo who helped Ieyasu to travel into safety were consisted 300 Ninjas.[19] Furthermore, Uejima Hidetomo, a researcher of Iga Ninja history, has stated there is research which revealed that Hattori Yasuji, one of the ninjas who accompanied Ieyasu on his journey in Iga province, also served as a bodyguard and espionage officer under Muromachi Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiaki.[28]

However, modern scholar such as Tatsuo Fujita doubted the credibility of Hattori Hattori Hanzō's ninja army theory, since it was first appeared in Iga-sha yuishogaki record which circulated in Edo period during the rule of Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune.[22] During his rule, Yoshimune were known for establishing the Oniwaban secret police institution which members hailed from the confederation clans of Koka and Iga.[29][30][31] It has been argued that the circulation of the myth about Hattori Hanzō ninja army helping Ieyasu were created as propaganda to increase the prestige of Iga and Koka clan confederations in Tokugawa Shogunate.[22]

On the other hand, Chaya Shirōjirō, a wealthy merchant in Kyoto, wrote that he went ahead and gave silver coins to local people and asked them to guide and escort the group, which is highly likely to be true since it also appears in Jesuit historical documents of the same period.[citation needed] However, the existence of Chaya Shirōjirō during this period itself also doubted by historians, since it was recorded that Shirōjirō were born in 1600, so it was unlikely he existed during Ieyasu travel in Iga province in 1582.[32]

Mitsuhide's betrayal theories

editThis section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Grammar and language. (May 2024) |

The Honnō-ji Incident is a major historical event, but no definitive conclusion has been reached regarding Akechi Mitsuhide's motives, and the truth remains unknown. More than 50 theories have been proposed over the years, and new theories emerge with each discovery of a new historical document or announcement of the results of an excavation.[2]

Betrayal motivation

editSeveral theories regarding the motivation:

- Mitsuhide was abused by Nobunaga, including being humiliated and dismissed as a receptionist for Tokugawa Ieyasu.[d] The prevailing theory during the Edo period was that the incident was caused by Mitsuhide's resentment of various unreasonable punishments he received from Nobunaga. The main reasons were as follows.[33] However, historian Tetsuo Owada considered such history, including alleged Mitsuhide's letter to Kobayakawa Takakage to express his feeling about Nobunaga as unreliable.[34]

- Nobunaga had treated him unfairly.[d] His fiefdom in the San'in region was unilaterally confiscated. Such theory includes the idication of preferential treatment for Oda Nobunaga's relatives. The theory is that Mitsuhide felt threatened by the fact that Nobunaga, who had previously adopted a merit-based system for his vassals and had appointed them according to their abilities regardless of their origins, began to favor his relatives.[35] Furthermore, there is an opinion that Nobunaga forcibly transferring Mitsuhide from his territory control of Sakamoto and Tanba into the yet to be conquered region of Izumo and Iwami. However, This theory also dismissed by Owada as It was usual custom for Nobunaga to bestow a non pacified territories yet to his vassals as promise.[34]

- His mother, who was a hostage of Hatano clan, was killed because of Nobunaga. During the siege of Yakami Castle in 1579 , Mitsuhide offered his mother as hostage to the Hatano clan, in an effort to convince Hatano Hideharu to submit to Nobunaga. However, Nobunaga instead executed Hideharu and his brother with crucifixion, prompting the Hatano clan to exact retaliation by crucified Mitsuhide's mother in response. However, there is no such mention in "Nobunaga Koki" a primary source. According to the book, Mitsuhide besieged Yakami Castle for a year, starving the enemy, and eventually captured the three Hatano brothers, but there is no mention of his mother being crucified afterwards. Furthermore, recent research has shown that she had died of natural cause before the siege of Yakami.[34] Modern historian Watanabe Daimon also explained this theory was traced from Toyama Nobuharu's work "Sōkenki" written around 1658; "Kashiwazaki Monogatari"; and also "Nobunaga-ki" (Shinchō Kōki); which Daimon also doubted their credibilities due to many embellishments and additions which was not found in primary sources found.[36]

Thus, these stories were largely deemed by historians as unreliable,[33][37] including the story of Mitsuhide betrayal from "Akechi-gunki" and "Kōyō Gunkan".[34]

Other new theories from 20th century historians which involve the Ashikaga Shogunate also emerged:

- There also emerged the theory that Mitsuhide was a loyalist to the imperial court or a shogunate vassal of the Ashikaga shogunate. Historian Kuwata Tadachika put forth the reason that Mitsuhide had a personal grudge, and there was another theory that Mitsuhide did not enjoy the cruelty of Nobunaga.[33][38]: 242 Another indication was when Mitsuhide began his march toward Chugoku, he held a renga session at the shrine on Mount Atago. The beginning line, Toki wa ima, ame ga shita shiru satsuki kana (時は今 雨がした滴る皐月かな), translates to "The time is now, the fifth month when the rain falls." However, there are several homonyms in the line, such that it could be taken as a double entendre. An alternate meaning, without changing any of the pronunciations, would be: 時は今 天が下治る 皐月かな. Thus it has also been translated as "Now is the time to rule the world: It's the fifth month!" In this case, the word toki, which means "time" in the first version, sounds identical to Akechi's ancestral family name, "Toki" (土岐).[38]

- Ashikaga Shogunate restoration, Tatsuo Fujita points out that Mitsuhide's handwritten letter addressed to the Kishu daimyo named Shigeharu Dobashi shows that Mitsuhide had a clear plan to welcome Yoshiaki to Kyoto after the Honnoji Incident and restore the Muromachi Shogunate.[39][40]

Alleged collaborators

editThe mastermind theory that someone behind the incident manipulated Mitsuhide Akechi to carry out Nobunaga's assassination is surprisingly new and has emerged since the 1990s. It all started when the well-known medieval historian Akira Imatani published a book advocating a conflict between the Imperial Court and Nobunaga. The theory is that the existence of an emperor with high authority was becoming a hindrance to Nobunaga, who wanted to be an absolute monarch. At the time, when the new emperor was about to ascend to the throne, the emperor system was the subject of much debate in the historical academia. Although Imatani himself did not claim that the Imperial Court was involved in the Honnō-ji Incident, various conspiracy theories were developed, mainly by influential historical researchers who were inspired by Imatani's theory.[33]

There are several theories about the collaborator of Mitsuhide's act in Honnō-ji:

- Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi theory[41]

- The reason is that Hideyoshi's Chugoku Ogaeshi was too fast. However, only the cavalry warriors were able to turn back at breakneck speed, and the infantry arrived late. Many of the soldiers did not make it in time for the "Battle of Yamazaki" with Mitsuhide.[33] While it might be a stretch to designate Hideyoshi as the mastermind, many historians have pointed out the strong possibility that he anticipated this situation.[42]

- Tokugawa Ieyasu theory[41]

- The reason is: "Nobunaga, who was on the verge of unifying the country, felt that Ieyasu, his ally, stood in his way. He planned to kill Ieyasu first. However, Mitsuhide, who was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with Nobunaga's policies, conversely informed Ieyasu of the plot and drew him into his side, thus killing Nobunaga by surprise." It is a leap of faith to assume that Mitsuhide and Ieyasu, who had not interacted with each other before, were able to conspire in Nobunaga's city, Azuchi Castle Town, and there is no historical support for this idea.[33]

- Ankokuji Ekei (the Mōri) theory

- The theory is that Ankokuji Ekei, a diplomatic monk of the Mōri, which was facing an existential crisis as Nobunaga himself was about to launch a full-scale offensive, arranged for Nobunaga's assassination on condition of the Mōri's full cooperation with Mitsuhide and Hideyoshi, and had it carried out.[2]

- Buddhist power theory

- The theory that Buddhist powers such as Hiei-zan Enryaku-ji and Ishiyama Hongan-ji, which were suppressed by Nobunaga and held a strong grudge against him, were the masterminds behind the situation.[2]

- Imperial Court/Kuge power theory

- This is the theory that Prince Masahito, Konoe Sakihisa, Yoshida Kanemi, and others forced Mitsuhide to defeat Nobunaga because Nobunaga forced Emperor Ōgimachi to abdicate. In reality, however, the Imperial Court was rather desperate to curry the favor of its sponsor, Nobunaga, since Nobunaga's financial support had dramatically improved their financial situation, which was in danger. Emperor Ōgimachi was also unable to abdicate due to a lack of funding for the abdication ceremony.[33]

- Ashikaga Shogun (Muromachi Shogunate) theory

- The theory is that Ashikaga Yoshiaki, the 15th shogun, exiled by Nobunaga, formed the Nobunaga siege by Mori Terumoto, Uesugi Kagakatsu, and other powerful Daimyo, and forced Mitsuhide to stage a coup d'état. However, the Shogun did not have much authority at the time, and Uesugi and Mori did not cooperate with Akechi.[33]

- Jesuit theory

- The theory is that the Jesuits of the Catholic Church, which dispatched missionaries to Japan, were the masterminds. The Jesuits supported Nobunaga militarily and economically, and Nobunaga also protected Christianity, but Nobunaga tried to become independent from the Jesuits by deifying himself, so the Jesuits had Mitsuhide defeat Nobunaga and then had Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi defeat Mitsuhide, according to this theory. However, while it is true that Nobunaga protected Christianity, there is no historical record of the Jesuits assisting Nobunaga on either the Japanese or Jesuit side, and in fact, the finances of the Japanese branch of the Jesuits were so tight that they could not afford to do so.[33]

In the 2010s, a Shikoku theory was proposed that Mitsuhide, who valued his relationship with Chōsokabe Motochika, rose up to avoid Nobunaga's attack on Shikoku. Mitsuhide was entrusted by Nobunaga to negotiate with Chōsokabe, and the Akechi family and Chōsokabe had deep ties in relation to marriage.[6][43] In 2020, NHK aired a program called "Honnoji Incident Summit 2020". Seven historians debated various theories, with the "Shikoku theory" garnering the most support.[44]

Popular culture

edit- Honnōji Hotel is a 2017 comedy mystery drama that takes places around the Honnō-ji Incident

- Tainei-ji incident – a similar coup in 1551 where a powerful daimyō of western Japan was forced to commit suicide

Appendix

editFootnotes

edit- ^ a b Court ladies.

- ^ a b A medieval Japanese custom in which local samurai, farmers and bandits hunt fleeing samurai for bounty and the valuables they wear.

- ^ The missionary Luis Frois wrote in his "History of Japan" that even the bones were burned to ashes.

- ^ a b In the "History of Japan" compiled by Luís Fróis, it is suggested that this is because Nobunaga, who did not like Mitsuhide's reception of Tokugawa Ieyasu, gave him a kick.

References

edit- ^ Naramoto, pp. 296–305

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Yamagishi, Ryoji (1 May 2017). "本能寺の変、「本当の裏切り者」は誰なのか 教科書が教えない「明智光秀」以外の真犯人" [Honnō-ji Incident, Who is the "real traitor"? The real culprit other than "Akechi Mitsuhide" that textbooks do not teach.]. Toyo Keizai Online (in Japanese). Toyo Keizai. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b "本能寺の変、信長の遺体はどこへ行ったのか?" [Where did Nobunaga's body go after the Honnoji Incident?]. Web Rekishi Kaido (in Japanese). PHP Institute, Inc. 2 June 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Owada, Yasutsune (16 October 2018). "本能寺の変、死を覚悟した信長がとった最期の行動" [The Honnoji Incident, Nobunaga's last act after preparing to die]. JBpress (in Japanese). Japan Business Press Co., Ltd. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b Turnbull, Stephen (2000). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & C0. p. 231. ISBN 1854095234.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kawai, Atsushi (3 January 2020). "天下統一を夢見た織田信長" [Oda Nobunaga, who dreamed of unifying the country] (in Japanese). Public Interest Incorporated Foundation, Nippon.com. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ "5カ国割譲を核とする講和案を秀吉に提示した。その交渉中に本能寺の変が起きた。". Nikkei Biz Gate. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ 林羅山 Razan, Hayashi, (compiled around 1641; published in 1658) 《織田信長譜》 (Oda Nobunaga-fu), "vol. 1"; quote: (光秀曰敵在本能寺); Aichi Prefectural Library's copy, p. 49 of 52, 9th column from right.

- ^ 日本外史 (Nihon Gaishi), "vol. 14" quote: (光秀乃擧鞭東指。颺言曰。吾敵在本能寺矣。); rough translation: "Mitsuhide lifted his whip, pointed eastward, and spoke loudly: 'My enemy is at Honnoji.'")

- ^ Horie, Hiroki (10 January 2021). "明智光秀「敵は本能寺にあり!」とは言っていない?" [Didn't Mitsuhide Akechi say, "The enemy is at Honnoji!"?]. Nikkan Caizo (in Japanese). Caizo. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Ito, Gaichi (9 February 2023). "信長の人物像を形作った「信長公記」執筆の背景 本能寺での最期の様子も現場の侍女に聞き取り" [Background of the writing of "Shincho Koki" that shaped the character of Nobunaga Interviews with waiting maids at the scene of Nobunaga's final days at Honnō-ji.]. Toyo Keizai Online (in Japanese). Toyo Keizai. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Ishikawa, Takuji (12 February 2021). "本能寺の変で信長が最後に発したひと言とは?" [What was Nobunaga's last words at the Honnoji Incident?]. GOETHE (in Japanese). Gentosha. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b Ishikawa, Takuji (6 March 2021). "本能寺の変で信長が最後に発したひと言とは?" [Nobunaga's last words to Nyōbō at the Honnoji Incident]. GOETHE (in Japanese). Gentosha. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (2010). Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 26-29. ISBN 9781846039607.

- ^ "本能寺の変、織田信忠の自害… 織田家の衰退がなかったらその後の「天下取り」はどうなった?" [Honnoji Incident, Oda Nobutada's suicide... If the Oda family hadn't declined, what would have happened to the unification of Japan?]. excite nesw (in Japanese). Excite Japan. 31 October 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Fujiki Hisashi (2005). 刀狩り: 武器を封印した民衆 (in Japanese). 岩波書店. p. 29・30. ISBN 4004309654.

Kunio Yanagita "History of Japanese Farmers"

- ^ a b Kirino Sakuto (2001). 真説本能寺 (学研M文庫 R き 2-2) (in Japanese). 学研プラス. pp. 218–219. ISBN 4059010421.

Tadashi Ishikawa quote

- ^ a b c d Akira Imatani (1993). 天皇と天下人. 新人物往来社. pp. 152–153, 157–158, 、167. ISBN 4404020732.

Akira Imatani"Practice of attacking fallen warriors"; 2000; p.153 chapter 4

- ^ a b Yamada Yuji (2017). "7. Tokugawa Ieyasu's passing through Iga". THE NINJA BOOK: The New Mansenshukai. Translated by Atsuko Oda. Mie University Faculty of Humanities, Law and Economics. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Masahiko Iwasawa (1968). "家忠日記の原本について" [(Editorial) Regarding the original of Ietada's diary] (PDF). 東京大学史料編纂所報第2号 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ a b (みちものがたり)家康の「伊賀越え」(滋賀県、三重県)本当は「甲賀越え」だった?忍者の末裔が唱える新説 [(Michi-monogatari) Ieyasu's "Iga's crossing (Shiga Prefecture, Mie Prefecture) Was it really "Koka-goe"? A new theory advocated by a ninja descendant] (in Japanese). Asahi Shimbun. 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Tatsuo Fujita (藤田達生) (2005). "「神君伊賀越え」再考". 愛知県史研究. 9. 愛知県: 1–15. doi:10.24707/aichikenshikenkyu.9.0_1.

- ^ Tatsuo Fujita. "Lecture No.1: Fact about "Shinkun Iga Goe" (1st Term) : Fact about "Shinkun Iga Goe" (1st Term) (summary)". Faculty of Humanities, Law and Economics & Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Kenshiro Kawanishi (川西賢志郎) (2023). "家康「伊賀越え」議論白熱 中部国際空港で初の国際忍者学会" [Ieyasu "Iga Cross" Discussion Hikari Central Airport's first international ninja society]. Sankei online (in Japanese). The Sankei Shimbun. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Fumitaka Kawasaki (1985). 徳川家康・伊賀越えの危難 [Tokugawa Ieyasu and the danger of crossing Iga]. 鳥影社. ISBN 4795251126. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ Masahiko Iwasawa (1968). "(Editorial) Regarding the original of Ietada's diary" (PDF). 東京大学史料編纂所報第2号. Retrieved 2022-11-16.

- ^ Morimoto Masahiro (1999). 家康家臣の戦と日常 松平家忠日記をよむ (角川ソフィア文庫) Kindle Edition. KADOKAWA. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Kenshiro Kawanishi (川西賢志郎) (2023). "「伊賀越え」同行忍者の経歴判明 家康と足利義昭の二重スパイか" ["Iga Cross" The history of the accompanying ninja is known to Ieyasu and Yoshiaki Ashikaga?]. Sankei online (in Japanese). The Sankei Shimbun. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Kacem Zoughari, Ph.D. (2013). Ninja Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan (The Secret History of Ninjutsu). Tuttle Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 9781462902873. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Samurai An Encyclopedia of Japan's Cultured Warriors. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. 2019. p. 203. ISBN 9781440842719. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ Stephen Turnbull (2017). Ninja Unmasking the Myth. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 9781473850439. Retrieved 10 May 2024.

- ^ https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/778970/37Ogawa Tokichi; Uno Kijiro (1900). 渡会の光 [Light of Watari] (in Japanese). 古川小三郎. pp. 60–61. Retrieved 18 May 2024. 角屋七郎次郎|朝日日本歴史人物事典

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Goza, Yuichi (13 July 2018). "「本能寺の変」のフェイクニュースに惑わされる人々" [People Misled by Fake News About the "Honnoji Incident".]. Nikkei BizGate (in Japanese). Nikkei, Inc. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Pinon (2019). "本能寺の変「怨恨説」~ 信長に対する不満・恨みが引き金だった!?" [The Honnoji Incident "Grudge Theory" - Was it triggered by dissatisfaction and resentment towards Nobunaga?]. 戦国ヒストリーのサイトロゴ (in Japanese). sengoku-his.com. Retrieved 2 July 2024. References from:

- Tetsuo Owada, Akechi Mitsuhide: The Rebel Who Was Created, PHP Institute, 1998.

- Tetsuo Owada, Akechi Mitsuhide and the Honnoji Incident, PHP Institute, 2014.

- Tatsuo Fujita, "Solving the Mystery of the Honnoji Incident", Kodansha, 2003.

- Taniguchi Katsuhiro, "Verification of the Honnoji Incident," Yoshikawa Kobunkan, 2007.

- Akechi Kenzaburo, "The Honnoji Incident: The Truth 431 Years Later," Bungeishunju Bunko, 2013.

- ^ Hashiba, Akira (21 July 2020). "光秀謀反の動機が見えた! 日本史最大の謎、信長暗殺の真相に迫る。" [The motive for Mitsuhide's rebellion is revealed! We will get to the bottom of the greatest mystery in Japanese history, the assassination of Nobunaga.]. Kadobun (in Japanese). KADOKAWA. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Watanabe Daimon (2024). "明智光秀の母と波多野三兄弟 あまりに残虐だった光秀による丹波八上城攻略の真実" [Akechi Mitsuhide's mother and the Hatano brothers: The truth behind Mitsuhide's brutal attack on Yakami Castle in Tanba]. 戦国ヒストリーのサイトロゴ (in Japanese). sengoku-his.com. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

- ^ Hashiba, Akira (10 August 2022). "茶道を人心掌握に活用した織田信長と荒稼ぎの千利休" [Oda Nobunaga, who used the tea ceremony to control people's minds, and Sen no Rikyū, who made a fortune.]. Wedge Online (in Japanese). Wedge. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ a b Sato, Hiroaki (1995). Legends of the Samurai. New York: Overlook Duckworth. p. 241,245. ISBN 9781590207307.

- ^ "本能寺の変、目的は室町幕府の再興だった? 明智光秀直筆の書状から分析" [The Honnoji Incident: Was the purpose the revival of the Muromachi Shogunate? Analysis from a letter handwritten by Akechi Mitsuhide]. ねとらぼ. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ^ "本能寺の変後、光秀の直筆手紙 紀州の武将宛て" [After the Honnoji Incident, Mitsuhide's handwritten letter to a lord in Kishu]. 『朝日新聞』. 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-09-12. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ^ a b Turnbull, Steven R. (1977). The Samurai: A Military History. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company. p. 164. ISBN 9780026205405.

- ^ "織田家臣団のなかで生き残りを懸けて光秀との派閥抗争の渦中にあった秀吉が、本能寺の変を事前に想定していた可能性は十分にある". KODANSHA LTD. 25 October 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

- ^ "謎に迫る新史料 光秀、四国攻め回避で決起か 林原美術館が明らかに". Sankei Shimbun. Tokyo. 23 June 2014. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2023 – via MSN.

New Historical Documents Reveal Mystery: Did Mitsuhide rise up to avoid the attack on Shikoku? Hayashibara Museum Revealed.

- ^ "信長の四国出兵の日に、本能寺の変は起きた。研究者の多くがこの説が有力であると首肯した。". Business Journal. Retrieved 30 April 2024.

Bibliography

edit- de Lange, William (2020). Samurai Battles: The Long Road to Unification. Toyo Press. ISBN 9789492722232.

- Naramoto Tatsuya (1994). Nihon no Kassen. Tokyo: Shufu to Seikatsusha.