The Mummy is a 1932 American pre-Code supernatural horror film directed by Karl Freund. The screenplay by John L. Balderston was adapted from a treatment written by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer. Released by Universal Studios as a part of the Universal Monsters franchise, the film stars Boris Karloff, Zita Johann, David Manners, Edward Van Sloan and Arthur Byron.

| The Mummy | |

|---|---|

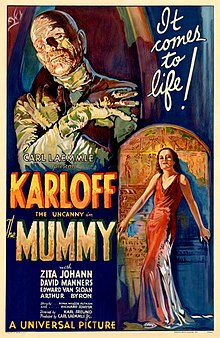

Theatrical release poster by Karoly Grosz[1] | |

| Directed by | Karl Freund |

| Screenplay by | John L. Balderston |

| Story by | |

| Produced by | Carl Laemmle Jr. |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Charles Stumar |

| Edited by | Milton Carruth |

| Music by | James Dietrich |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 73 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $196,000[3] |

In the film, Karloff stars as Imhotep, an ancient Egyptian mummy who was killed for attempting to resurrect his dead lover, Anck-es-en-Amon. After being discovered and accidentally brought to life by a team of archaeologists, he disguises himself as a modern Egyptian named Ardath Bey and searches for Anck-es-en-Amon, whom he believes has been reincarnated in the modern world.

While less profitable than its predecessors Dracula and Frankenstein, The Mummy was still a commercial and critical success, becoming culturally influential and spawning several sequels, spin-offs, remakes, and reimaginings.[4] The film and its sequels cemented the mummy archetype as a staple of the horror genre and Halloween festivities.[5]

Plot

editIn 1921, an archaeological expedition led by Sir Joseph Whemple finds the mummy of an ancient Egyptian high priest named Imhotep. An inspection of the mummy by Whemple's friend Dr. Muller reveals that the mummy's viscera were not removed, and from the signs of struggling Muller deduces that although Imhotep had been wrapped like a traditional mummy, he had been buried alive. Also buried with Imhotep is a casket with a curse on it. Despite Muller's warning, Sir Joseph's assistant Ralph Norton opens it and finds an ancient life-giving scroll, the "Scroll of Thoth". He translates the symbols and then reads the words aloud, causing Imhotep to rise from the dead. This snaps Norton's mind, and he laughs hysterically as Imhotep shuffles off with the scroll. Norton is said to later die, still laughing, in a straitjacket.

Ten years later, Imhotep has assimilated into modern society, taking the identity of an eccentric Egyptian historian named Ardath Bey. He calls upon Sir Joseph's son Frank and Professor Pearson and shows them where to dig to find the tomb of the princess Ankh-es-en-Amon. After locating the tomb, the archaeologists present its treasures to the Cairo Museum, after which Bey disappears.

Bey soon encounters Helen Grosvenor, a half-Egyptian woman bearing a striking resemblance to the princess, who stays with Muller. Bey falls in love with her but so does Frank. After it is discovered that Bey is the mummy Imhotep, Muller urges Joseph to burn the Scroll of Thoth, but when Joseph tries to do so, Bey uses his magical powers to kill him and then hypnotizes a Nubian to be his slave and bring the Scroll to him. After the servant does so, he hypnotizes Helen to come to his place and there, reveals to her that his horrific death was punishment for sacrilege, as he attempted to resurrect his lover, Princess Anck-es-en-Amon.

Believing her to be the princess's reincarnation, he attempts to make her his immortal bride by killing, mummifying, and resurrecting her. Frank and Muller come to her rescue but are immobilized by Bey's magical powers. However Helen is saved when she remembers her ancestral past life and prays to the goddess Isis to come to her aid. The statue of Isis raises its arm and emits a flash that sets the Scroll of Thoth on fire. This breaks the spell that had given Imhotep his immortality, causing him to crumble to dust. At the urging of Dr. Muller, Frank calls Helen back to the world of the living while the Scroll continues to burn.

Cast

edit- Boris Karloff (billed as "Karloff") as Ardath Bey[6] / Im-ho-tep[6] / The Mummy, an Ancient Egyptian high priest mummified for trying to revive his lover who is later revived in 1921 and who searches and finds his lost love in 1930s Egypt after many years in 1932

- Zita Johann as Helen Grosvenor, a young British-Egyptian woman preyed on by Imhotep / Princess Anck-es-en-Amon, Helen's lookalike ancestor/past life and Imhotep's ancient lover whom he tries to revive [6]

- David Manners as Frank Whemple, an archaeologist and Helen's lover

- Arthur Byron as Sir Joseph Whemple, a retired archaeologist and Frank's father

- Edward Van Sloan as Dr. Muller, Joseph and Frank's colleague

- Bramwell Fletcher as Ralph Norton, Joseph's archaeology protegé

- Noble Johnson as The Nubian, Joseph's and later Imhotep's servant

- Kathryn Byron as Frau Muller, Dr. Muller's wife

- Leonard Mudie as Professor Pearson, Frank's expedition partner and an archaeologist

- James Crane as Pharaoh (misspelled as "Pharoh" in the credits) Amenophis, Princess Anck-es-en-Amon's father and ruler of Ancient Egypt

- Montague Shaw as Gentleman, who appears at the party that Helen attends

- Henry Victor as The Saxon Warrior (scenes deleted)[a]

Production

editInspired by the opening of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922 and the alleged "curse of the pharaohs",[7] producer Carl Laemmle Jr. commissioned story editor Richard Schayer to find a novel to form a basis for an Egyptian-themed horror film, just as the novels Dracula and Frankenstein inspired their 1931 films Dracula and Frankenstein.[8] Schayer found none, although the plot bears a strong resemblance to a short story by Arthur Conan Doyle entitled "The Ring of Thoth".[9] Schayer and writer Nina Wilcox Putnam learned about Alessandro Cagliostro and wrote a nine-page treatment entitled Cagliostro.[8] The story, set in San Francisco, was about a 3,000-year-old magician who survives by injecting nitrates.[citation needed]

Pleased with the Cagliostro concept, Laemmle hired John L. Balderston to write the script.[8] Balderston had contributed to Dracula and Frankenstein, and had covered the opening of Tutankhamun's tomb for the New York World when he was a journalist so he was more than familiar with the well publicised tomb unearthing. Balderston moved the story to Egypt and renamed the film and its title character Imhotep, after the historical architect.[10] He also changed the story from one of revenge upon all the women who resembled the main character's ex-lover to one where the main character is determined to revive his old love by killing and mummifying her reincarnated self before resurrecting her with the spell of the Scroll of Thoth.[11] Balderston invented the Scroll of Thoth, which gave an aura of authenticity to the story. Thoth was the wisest of the Egyptian gods who, when Osiris died, helped Isis bring her love back from the dead. Thoth is believed to have authored The Book of the Dead, which may have been the inspiration for Balderston's Scroll of Thoth. Another likely source of inspiration is the fictional Book of Thoth that appeared in several ancient Egyptian stories.[12]

Karl Freund, the cinematographer on Dracula, was hired to direct, making this his first film in the United States as a director.[13] Freund had also been the cinematographer on Fritz Lang's Metropolis. The film was retitled The Mummy. Freund cast Zita Johann, who believed in reincarnation, and named her character 'Anck-es-en-Amon' after the only wife of Pharaoh Tutankhamun. The real Ankhesenamun's body had not been discovered in the tomb of King Tutankhamun and her resting place was unknown. Her name, however, would not have been unknown to the general public.[citation needed]

Filming began in September 1932 and was scheduled for three weeks.[14] Karloff's first day was spent shooting the Mummy's awakening from his sarcophagus. Make-up artist Jack Pierce had studied photos of Seti I's mummy to design Imhotep. Pierce began transforming Karloff at 11 a.m., applying cotton, collodion and spirit gum to his face; clay to his hair; and wrapping him in linen bandages treated with acid and burnt in an oven, finishing the job at 7 p.m. Karloff finished his scenes at 2 a.m., and another two hours were spent removing the make-up. Karloff found the removal of gum from his face painful, and overall found the day "the most trying ordeal I [had] ever endured".[10] Although the images of Karloff wrapped in bandages are the most iconic taken from the film, Karloff appears on screen in this make-up only for the opening vignette; the rest of the film sees him wearing less elaborate make-up.[15]

A lengthy and detailed flashback sequence was longer than now exists. This sequence showed the various forms Anck-es-en-Amon was reincarnated in over the centuries:[16] Henry Victor is credited in the film as "Saxon Warrior", despite his performance having been deleted.[17] Stills exist of those sequences, but the footage (save for Karloff's appearance and the sacrilegious events leading up to his mummification in ancient Egypt) are lost.[18]

The piece of classical music heard during the opening credits, taken from the Tchaikovsky ballet Swan Lake, was previously also used (in the same arrangement) for the opening credits of Universal's Dracula (1931) and Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932); it would be re-used as the title music of the same studio's Secret of the Blue Room (1933).[citation needed]

Historical accuracy

editThe Scroll of Thoth is a fictional artifact, though likely based on the Book of the Dead. Thoth, the Egyptian god of knowledge, is said to be the inventor of hieroglyphs and the author of the Book of the Dead. The film also makes reference to the Egyptian myth of the goddess Isis resurrecting Osiris after his murder by his brother Set.

Conspirators were caught in a plot to assassinate Pharaoh Ramesses III around 1151 B.C. Papyrus trial transcripts reveal that the conspirators were prescribed 'great punishments of death', and archaeological evidence led to the suggestion that at least one of them may have been buried alive. Although such punishment was not common practice, this discovery probably influenced the film's screenplay.[12]

There is no evidence to suggest that the ancient Egyptians believed in or considered the possibility of reanimated mummies. Mummification was a sacred process meant to prepare a dead body to carry the soul through the afterlife, not for being reincarnated and living again on Earth. While it is possible that some individuals were mummified by being buried alive, it is unlikely that ancient Egyptians would think resurrection was possible because they were very aware of the fact that all the necessary organs had been removed and the body would be of little use on Earth anymore.[11] Egyptologist Stuart Tyson Smith notes that 'the idea of mobile mummies was not entirely alien to ancient Egypt', citing one of the Hellenistic-era stories of Setna Khaemwas, which features both the animated mummy of Naneferkaptah and a fictional Book of Thoth and may have inspired screenwriter John Balderston.[12]

Reception

editThe Los Angeles Times was positive, although the film otherwise gained mixed critical reviews despite being a modest box office success.[19] When the film opened at New York's RKO Mayfair theater, a reviewer for The New York Times was ultimately unimpressed:

For purposes of terror there are two scenes in The Mummy that are weird enough in all conscience. In the first the mummy comes alive and a young archaeologist, going quite mad, laughs in a way that raises the hair on the scalp. In the second Im-Ho-Tep is embalmed alive, and that moment when the tape is drawn across the man's mouth and nose, leaving only his wild eyes staring out of the coffin, is one of decided horror. But most of The Mummy is costume melodrama for the children.[20]

The film was a success at the box-office in the United Kingdom.

Review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes reports an 89% score, based on 45 reviews, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The site's consensus states: "Relying more on mood and atmosphere than the thrills typical of modern horror fare, Universal's The Mummy sets a masterful template for mummy-themed films to follow".[21]

Cliff Aliperti at Immortal Ephemera opines: "The perfect explanation of The Mummy's quality comes from film historian William K. Everson's closing comment in the brief Mummy section of his 1974 Classics of the Horror Film: 'If one accepts The Bride of Frankenstein for its theatre and The Body Snatcher for its literacy, then one must regard The Mummy as the closest that Hollywood ever came to creating a poem out of horror'."[22]

The Mummy has been decried for "othering" Eastern culture, especially portraying it as being more primitive and superstitious than Western culture. In one scene, Helen Grosvenor longs for the "real" (Classical) Egypt, disparaging that she is in contemporary Islamic Egypt. This is viewed by critic Caroline T. Schroeder as a slight against Islamic culture at the time.[23] However, it is clear that Helen longs to be in Ancient Egypt (but does not know why) because she had been reincarnated, living in present day, but had originally lived in Ancient Egypt.

According to Mark A. Hall, of the Perth Museum and Art Gallery, film portrayals of Egypt, especially in Egyptian archaeology, often deal with themes of appropriating and controlling the dangers of non-European cultures, or deal with the past if it relates to legend and superstition. Mummies, Hall says, are a common example of this. While he commended the archaeological wisdom espoused by Sir Joseph Whemple in the film, he writes that "much more is learned from studying bits of broken pottery than from all the sensational finds" and that archaeologists' job is to "increase the sum of human knowledge of the past", and mentions that the archaeological element was only used as a foil for the supernatural elements.[24] As a result, per Hall, what it and similar films offered was a "depiction of archaeology as a colonial imposition by which cultural inheritance is appropriated".[24]

Legacy

editSequels

editUnlike other Universal Monsters films, The Mummy had no official sequel. The character was re-imagined in The Mummy's Hand (1940) and its sequels; The Mummy's Tomb (1942), The Mummy's Ghost (1944), The Mummy's Curse (1944), and the studio's comedy–horror crossover film Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy (1955). These films focus on the titular character named Kharis (Klaris in the Abbott and Costello film). The Mummy's Hand recycled footage from the original film for use in the telling of Kharis's origins, where Karloff is clearly visible in several of these recycled scenes but was not credited. Lon Chaney Jr. played the Mummy in The Mummy's Tomb, The Mummy's Ghost, and The Mummy's Curse.

Hammer Film Productions series

editIn the late 1950s, British Hammer Film Productions took up the Mummy theme, beginning with The Mummy (1959), which, rather than being a remake of the 1932 Karloff film, is based on Universal's The Mummy's Hand (1940) and The Mummy's Tomb (1942). Hammer's follow-ups — The Curse of the Mummy's Tomb (1964), The Mummy's Shroud (1966) and Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (1971) — are unrelated to the first film or even to each other, apart from the appearance of The Scroll of Life in Curse of the Mummy's Tomb and Blood from the Mummy's Tomb.

Remake series

editThe much later Universal film The Mummy (1999) also suggests that it is a remake of the 1932 film, but has a different storyline and is more similar to The Mummy's Hand than the original. In common with most postmodern remakes of classic horror and science-fiction films, it may be considered as such in that it is produced-distributed by the same studio, its titular character is again named Imhotep, resurrected by the Book of the Dead, and out to find the present-day embodiment of the soul of his beloved Anck-su-namun, and features an Egyptian named Ardeth Bay (in this case, a guard of the city and of Imhotep's tomb). This film spawned two sequels with The Mummy Returns (2001) and The Mummy: Tomb of the Dragon Emperor (2008). The Mummy Returns also spawned a prequel spin-off of that sequel, The Scorpion King (2002), which in turn spawned a prequel, The Scorpion King 2: Rise of a Warrior (2008), and three sequels, The Scorpion King 3: Battle for Redemption (2012), The Scorpion King 4: Quest for Power (2015) and Scorpion King: Book of Souls (2018). Also, a short-lived animated series simply titled The Mummy ran from 2001 to 2003.

Reboot

editIn 2012, Universal announced a reboot of the film, more in-line with the horror films, from the Universal Monsters film franchise.[25] The reboot was directed by Alex Kurtzman. The Mummy was planned as the first film in a series of interconnected monster films, as Universal has planned to build a shared universe film series out of its vault of classic monster movies.[26] Tom Cruise stars in the film.[27] Sofia Boutella portrays Princess Ahmunet / The Mummy for the film, while Russell Crowe appears as Dr. Henry Jekyll / Mr. Hyde, two roles which had previously been portrayed by Boris Karloff in the studios' previous film franchise. It received negative reviews and is considered a box office bomb, scrapping the plans for the upcoming films of the Dark Universe.

Honors

editThe film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2001: AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – Nominated[28]

- 2003: AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains:

Home media

editIn the 1990s, MCA/Universal Home Video released The Mummy on VHS as part of the "Universal Monsters Classic Collection", a series of releases of Universal Classic Monsters films.[30] The film was also released on LaserDisc.[31]

In 1999, Universal released The Mummy on VHS and DVD as part of the "Classic Monster Collection".[32][33] In 2004, Universal released The Mummy: The Legacy Collection on DVD as part of the "Universal Legacy Collection". On October 19, 2004, Universal released The Mummy: The Legacy Collection on DVD as part of the "Universal Legacy Collection"; this two-disc set also includes The Mummy's Hand, The Mummy's Tomb, The Mummy's Ghost, and The Mummy's Curse.[34] In 2008, Universal released The Mummy on DVD as a two-disc "75th Anniversary Edition", as part of the "Universal Legacy Series".[35]

In 2012, The Mummy was released on Blu-ray as part of the Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection box set, which includes a total of nine films from the Universal Classic Monsters series.[36] The following year, The Mummy was included as part of the six-film Blu-ray set Universal Classic Monsters Collection, which also includes Dracula, Frankenstein, The Invisible Man, Bride of Frankenstein, and The Wolf Man.[37] In 2015, the six-film set was issued on DVD.[38] In 2014, Universal released The Mummy: Complete Legacy Collection on DVD; this set contains six films: The Mummy, The Mummy's Hand, The Mummy's Tomb, The Mummy's Ghost, The Mummy's Curse, and Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy.[39] In 2016, The Mummy received a Walmart-exclusive Blu-ray release featuring a glow-in-the-dark cover.[40] In September 2017, the film received a Best Buy-exclusive steelbook Blu-ray release with cover artwork by Alex Ross.[41] That same year, the six-film Complete Legacy Collection was released on Blu-ray.[42]

In August 2018, The Mummy, The Mummy's Hand, The Mummy's Tomb, The Mummy's Ghost, The Mummy's Curse, and Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy were included in the Universal Classic Monsters: Complete 30-Film Collection Blu-ray box set.[43] This box set also received a DVD release.[44] Later in October, The Mummy was included as part of a limited edition Best Buy-exclusive Blu-ray set titled Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection, which features artwork by Alex Ross.[45]

References

edit- ^ Michaud, Chris (October 31, 2018). "'Mummy' film poster, expected to fetch record, fails to sell at auction". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 1, 2018.

- ^ "THE MUMMY (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. October 4, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Stephen Jacobs, Boris Karloff: More Than a Monster, Tomahawk Press 2011, pp. 127-130

- ^ "The Mummy | Horror Classic, Universal Pictures, Karl Freund | Britannica". www.britannica.com. March 21, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ Schmitt, Morgan (October 28, 2020). "'The Mummy,' now on Prime, remains Halloween classic". UWIRE Text: 1.

- ^ a b c Character's name spelled according to original typescript screenplay by John L. Balderston, published in The Mummy (1st ed.). MagicImage Filmbooks. March 18, 1989. ISBN 1-882127-07-2.

- ^ Miller, Frank (December 29, 2002). "The Mummy (1932) - The Mummy". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b c Robson, David (2012). The Mummy. San Diego: Capstone. p. 11. ISBN 9781601523204. OCLC 882287316.

- ^ "The Ring of Thoth". Retrieved October 12, 2019.

- ^ a b Vieira, Mark A. (2003). Hollywood Horror: From Gothic to Cosmic. New York: Harry N. Abrams. pp. 55–58. ISBN 0-8109-4535-5.

- ^ a b Freeman, Richard (March 18, 2009). "THE MUMMY in context". European Journal of American Studies. 4 (1). doi:10.4000/ejas.7566.

- ^ a b c Smith, Stuart Tyson (2007) "Unwrapping the Mummy: Hollywood Fantasies, Egyptian Realities" in Box Office Archaeology: Refining Hollywood's Portrayals of the Past (ed. Julie M. Schablitsky), Left Coast Press, page 20–21; ISBN 978-1598740561

- ^ "Articles: Turner Classic Movies". Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Robson 2012, p. 12.

- ^ Mank, Gregory W. (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. pp. 126–128. ISBN 9780786434800. OCLC 607553826.

- ^ Mank, Gregory W. (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. pp. 126, 131, 133. ISBN 9780786434800. OCLC 607553826.

- ^ Mank, Gregory W. (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. p. 133. ISBN 9780786434800. OCLC 607553826.

- ^ Mank, Gregory W. (2009). Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: the expanded story of a haunting collaboration, with a complete filmography of their films together. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., Publishers. p. 134. ISBN 9780786434800. OCLC 607553826.

- ^ Robson 2012, p. 13.

- ^ "Life After 3,700 Years". The New York Times. January 7, 1933. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- ^ "The Mummy (1932)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 29, 2021.

- ^ "Moments of Horror as Boris Karloff Stars as The Mummy (1932)". Immortal Ephemera. October 29, 2010. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Schroeder, Carolyn T. Ancient Egyptian Religion on the Silver Screen: Modern Anxieties about Race, Ethnicity, and Religion. University of Nebraska Omaha. Oct 2003. January 20, 2015.

- ^ a b Hall, Mark A. "Romancing the stones: archaeology in popular cinema". European Journal of Archaeology 7.2 (2004): p. 161.

- ^ Kroll, Justin, Snieder, Jeff, "U sets 'Mummy' reboot with Spaihts", Variety.com, Published 2012-04-04, Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (October 14, 2015). "New Mummy in Universal's Monster Universe Might Be Female". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (January 21, 2016). "Tom Cruise's 'The Mummy' Gets New Release Date". Variety. Retrieved January 21, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2022.

- ^ The Mummy (Universal Monsters Classic Collection) [VHS]. ASIN 6300183084.

- ^ "The Mummy (Encore Edition) [40030]". LaserDisc Database. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ The Mummy (Classic Monster Collection) [VHS]. ISBN 0783234287.

- ^ Arrington, Chuck (May 4, 2000). "Mummy-1932, The". DVD Talk. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Erickson, Glenn (October 19, 2004). "DVD Savant Review: The Mummy: The Legacy Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Felix, Justin (July 10, 2008). "Mummy (1932), The". DVD Talk. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Zupan, Michael (October 5, 2012). "Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection". DVD Talk. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters Collection [DVD]". Amazon.com. September 8, 2015. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "The Mummy: Complete Legacy Collection [DVD]". Amazon.com. September 2, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Squires, John (September 13, 2016). "Walmart Releases Universal Monsters Classics With Glow-In-Dark Covers!". iHorror.com. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Squires, John (June 27, 2017). "Best Buy Getting Universal Monsters Steelbooks With Stunning Alex Ross Art". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ^ "The Mummy: Complete Legacy Collection [Blu-ray]". Amazon.com. May 16, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: Complete 30-Film Collection [Blu-ray]". Amazon.com. August 28, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "Classic Monsters (Complete 30-Film Collection) [DVD]". Amazon.com. September 2, 2014. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ "Universal Classic Monsters: The Essential Collection Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

Notes

edit- ^ Victor is listed in the credits but never appears in the film. The Saxon Warrior was originally part of a long flashback sequence showing all of Helen's past lives from ancient Egypt to the present. The sequence was cut from the film by Karl Freund due to time constraints.

Bibliography

edit- Telotte, J. P. (July 2003). "Doing Science in Machine Age Horror: 'The Mummy''s Case". Science Fiction Studies. 30 (2): 217–230. ISSN 0091-7729. JSTOR 4241170.

External links

edit- Quotations related to The Mummy at Wikiquote

- Media related to The Mummy at Wikimedia Commons

- The Mummy at IMDb

- The Mummy at AllMovie

- The Mummy at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Mummy at the TCM Movie Database

- The Mummy at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films