Netherlands in World War II

Despite Dutch neutrality, Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands on 10 May 1940 as part of Fall Gelb (Case Yellow).[1] On 15 May 1940, one day after the bombing of Rotterdam, the Dutch forces surrendered. The Dutch government and the royal family relocated to London. Princess Juliana and her children sought refuge in Ottawa, Canada until after the war.

German occupation lasted in some areas until the German surrender in May 1945. Active resistance, at first carried out by a minority, grew in the course of the occupation.[citation needed] The occupiers deported the majority of the country's Jews to Nazi concentration camps.[2]

Due to the high variation in the survival rate of Jewish inhabitants among local regions in the Netherlands, scholars have questioned the validity of a single explanation at the national level. In part due to the well-organised population registers, about 70% of the country's Jewish population were killed in the course of World War II—a much higher percentage than in either Belgium or France,[3] although lower than in Lithuania. Declassified records revealed that the Germans paid a bounty to Dutch police and administration officials to locate and identify Jews, aiding in their capture.[4] Communists in and around the city of Amsterdam organised the February strike—a general strike (February 1941) to protest against the persecution of Jewish citizens.

World War II occurred in four distinct phases in the Netherlands:

- September 1939 to May 1940: After the war broke out, the Netherlands declared neutrality. The country was subsequently invaded and occupied.

- May 1940 to June 1941: An economic boom caused by orders from Germany, combined with the "velvet glove" approach from Arthur Seyss-Inquart, resulted in a comparatively mild occupation.

- June 1941 to June 1944: As the war intensified, Germany demanded higher contributions from occupied territories, resulting in a decline of living standards. Repression against the Jewish population intensified and thousands were deported to extermination camps. The "velvet glove" approach ended.

- June 1944 to May 1945: Conditions deteriorated further, leading to starvation and lack of fuel. The German occupation authorities gradually lost control over the situation. Nazis wanted to make a last stand and commit acts of destruction. Others tried to mitigate the situation.

The Allies liberated most of the south of the Netherlands in the second half of 1944. The rest of the country, especially the west and north, remained under German occupation and suffered from a famine at the end of 1944, known as the "Hunger Winter". On 5 May 1945, German surrender at Lüneburg Heath led to the final liberation of the whole country.

Background

editThe Dutch colonies such as the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia) caused the Netherlands to be one of the top five oil producers in the world at the time and to have the world's largest aircraft factory in the Interbellum (Fokker), which aided the neutrality of the Netherlands and the success of its arms dealings in the First World War. The country was one of the richest in Europe and could easily have afforded a large and modern military [citation needed]. Dutch governments between 1929 and 1943 were dominated by Christian and centre-right political parties.[5] From 1933, the Netherlands were hit by the Great Depression, which had begun in 1929.[5] The incumbent government of Hendrikus Colijn pursued a programme of extensive cuts to maintain the value of the guilder, which resulted in workers' riots in Amsterdam and a naval mutiny between 1933 and 1934.[5] Eventually, in 1936, the government was forced to abandon the gold standard and to devalue the currency.[5]

Numerous fascist movements emerged in the Netherlands during the Great Depression era, which were inspired by Italian fascism or German Nazism, but they never attracted enough members to be an effective mass movement. The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands (Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, NSB) supported by the National Socialist German Workers' Party which took power in Germany in 1933, attempted to expand in 1935. Nazi-style racial ideology had limited appeal in the Netherlands, as did its calls to violence.[6] At the outbreak of the Second World War, the NSB was already declining in both members and voters.

During the interwar period, the government undertook a significant increase in civil infrastructure projects and land reclamation, including the Zuiderzee Works. That resulted in the final draining of seawater from the Wieringermeer polder and the completion of the Afsluitdijk.[5]

Neutrality

edit"The new Reich has endeavored to continue the traditional friendship with Holland [sic]. It has not taken over any existing differences between the two countries and has not created any new ones."

During World War I, the Dutch government, under Pieter Cort van der Linden, had managed to preserve Dutch neutrality throughout the conflict.[8] In the Interwar Period, the Netherlands had continued to pursue its "Independence Policy" even after the rise to power of the Nazi Party in Germany in 1933.[9] The Anti-Revolutionary Party's conservative prime minister, Hendrikus Colijn, who held power from 1933 until 1939, believed that the Netherlands could never withstand an attack by a major power. Pragmatically, the government did not spend much on the military.[10] Although military spending was doubled between 1938 and 1939, amid rising international tensions, it constituted only 4% of national spending in 1939, in contrast to nearly 25% of Nazi Germany.[10] The Dutch government believed it could rely on its neutrality or at least the informal support of foreign powers to defend its interests in case of war.[10] The government began to work on plans for the defence of the country,[11] which included the "New Dutch Waterline", an area to the east of Amsterdam that would be flooded. From 1939, fortified positions were constructed, including the Grebbe and Peel-Raam Lines, to protect the key cities of Dordrecht, Utrecht, Haarlem and Amsterdam, and creating a Vesting Holland (or "Fortress Holland").[11]

In late 1939, with war already declared between the British Empire, France and Nazi Germany, the German government issued a guarantee of neutrality to the Netherlands.[7] The government gradually mobilised the Dutch military from August 1939 that had reached its full strength by April 1940.[11]

German invasion

editDespite its policy of neutrality, the Netherlands were invaded on the morning of 10 May 1940, without a formal declaration of war, by German forces moving simultaneously into Belgium and Luxembourg.[12] The attackers meant to draw Allied forces away from the Ardennes and to lure British and French forces deeper into Belgium and to pre-empt a possible British invasion in North Holland. The Luftwaffe needed to take over the Dutch airfields on the North Sea to launch air raids against the United Kingdom.

The armed forces of the Netherlands, with insufficient and outdated weapons and equipment, were caught largely unprepared.[11] Much of their weaponry had not changed since the First World War.[13] In particular, the Royal Netherlands Army did not have comparable armoured forces and could mount only a limited number of armoured cars and tankettes.[14] The air force had only 140 aircraft, mostly outdated biplanes.[15] Sixty-five of the Dutch aircraft were destroyed on the first day of the campaign.[16]

The invading forces advanced rapidly but faced significant resistance. A Wehrmacht parachute assault on the first day, aimed at capturing the Dutch government in The Hague and the key airfields at Ockenburg and Ypenburg, was defeated by Dutch ground forces with heavy casualties.[17] The Dutch succeeded in destroying significant numbers of transport aircraft that the Germans would need for their planned invasion of Britain. However, the German forces succeeded in crossing the Maas river in the Netherlands on the first day, which allowed the Wehrmacht to outflank the nearby Belgian Fort Ében-Émael and force the Belgian army to withdraw from the German border.[18]

In the eastern Netherlands, the Germans succeeded in pushing the Dutch back from the Grebbe Line, but their advance was slowed by the Dutch fortifications on the narrow Afsluitdijk Causeway that linked the north-eastern and the north-western parts of the Netherlands.[19] The German forces advanced rapidly and, by the fourth day, were in control of most of the east of the country.[19]

The Dutch realised that neither British nor French troops could reach the Netherlands in sufficient numbers to halt the invasion, particularly with the speed of the German advance into Belgium.[19]

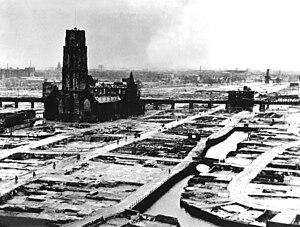

Bombing of Rotterdam

editFighting in Rotterdam had taken place since the first day of the campaign, when German infantrymen in seaplanes landed on the Maas River and captured several bridges intact. The Germans hesitated to risk a tank attack on the city for fear of heavy casualties. Instead, the German commander presented an ultimatum to the Dutch commander in the city. He demanded the surrender of the Dutch garrison and threatened to destroy the city by aerial bombing if it did not accept.[20] The ultimatum was returned on a technicality since it had not been signed by the German commander.[20] While the corrected ultimatum was being resubmitted, Luftwaffe bombers, unaware that negotiations were ongoing, struck the city.[20]

During the Rotterdam Blitz, between 800 and 900 Dutch civilians were killed, and 25,000 homes were destroyed.[20] The bombers' targets were the civilian areas of Rotterdam, rather than the town's defences.[20] Under pressure from local officials, the garrison commander surrendered the city and his 10,000 men on the evening of the 14th with the permission of Henri Winkelman, the Dutch commander-in-chief. That opened up the German advance into "Fortress Holland".[20]

Dutch surrender

editThe Dutch high command was shocked by the Rotterdam Blitz. Knowing that the army was running low on supplies and ammunition and receiving news that the city of Utrecht had been given an ultimatum similar to that of Rotterdam,[16] Winkelman held a meeting with other Dutch generals. They decided that further resistance was futile and wanted to protect civilian residents. In the afternoon of 14 May, Winkelman issued a proclamation to his army to order them to surrender:

This afternoon Germany bombarded Rotterdam, while Utrecht has also been threatened with destruction. In order to spare the civil population and to prevent further bloodshed I feel myself justified in ordering all troops concerned to suspend operations ... By great superiority of the most modern means [the enemy] has succeeded in breaking our resistance. We have nothing wherewith to reproach ourselves in connection with this war. Your bearing and that of the forces was calm, firm of purpose and worthy of the Netherlands.

— Proclamation of General Winkelman, 14 May 1940.[21]

On 15 May, the Netherlands officially signed the surrender with Germany. Dutch forces in the province of Zeeland, which had come under French control, continued fighting alongside French forces until 17 May, when the bombardment of the town of Middelburg forced them to surrender also. The Dutch Empire, in particular the Dutch East Indies, supported the Allies; the colonies were unaffected by the surrender. Many ships of the Royal Dutch Navy in Dutch waters fled to the United Kingdom.[22]

During the four-day campaign, about 2,300 Dutch soldiers were killed and 7,000 wounded, and more than 3,000 Dutch civilians also died. The Germans lost 2,200 men killed and 7,000 wounded. In addition, 1,300 German soldiers captured by the Dutch during the campaign, many around The Hague, had been shipped to Britain and remained POWs for the rest of the war.

Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government succeeded in escaping from the Netherlands before the surrender and formed a government-in-exile. Princess Juliana and her children went to Canada for safety.

German occupation

editLife in occupied Netherlands

editInitially, the Netherlands was placed under German military control. However, after the refusal of the Dutch government to return, the Netherlands was placed under control by a German civilian governor on 29 May 1940, unlike France or Denmark, which had their own governments, and Belgium, which was under German military control. The civil government, the Reichskommissariat Niederlande, was headed by the Austrian Nazi Arthur Seyss-Inquart.

The German occupiers implemented a policy of Gleichschaltung ("enforced conformity" or "coordination") and systematically eliminated non-Nazi organisations. In 1940, the German regime more or less immediately outlawed all socialist and communist parties. In 1941, it forbade all parties except for the National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands.

Gleichschaltung was an enormous shock to the Dutch, who had traditionally had separate institutions for all main religious groups, particularly Catholic and Protestant, because of decades of pillarisation. The process was opposed by the Catholic Church in the Netherlands, and in 1941, all Roman Catholics were urged by Dutch bishops to leave associations that had been Nazified.

A long-term aim of the Nazis was to incorporate the Netherlands into the Greater Germanic Reich.[23] Adolf Hitler thought very highly of the Dutch people, who were considered to be fellow members of the Aryan "master race".[24]

Initially, Seyss-Inquart applied the 'velvet glove' approach; by appeasing the population he tried to win them for the National Socialist ideology. That meant that he kept repression and economic extraction as low as possible and tried to co-operate with the elite and government officials in the country. There was also a pragmatic reason since the NSB offered insufficient candidates and had no great popular support. The German market went open, and Dutch companies benefited greatly from export to Germany even if that might be seen as collaboration if goods might be used for German war efforts. In any case, despite the British victory in the Battle of Britain, many considered a German victory a realistic possibility and that it would therefore be wise to side with the winner. As a result, with the ban on other political parties, the NSB grew rapidly. Although gasoline pumps had been sealed in 1940, the occupation seemed tolerable.

After the failure of Operation Barbarossa in June 1941 and the subsequent German defeats at Moscow and Stalingrad in the Eastern Front of World War II, Germany increased economic extraction from its occupied territories, including the Netherlands. Economic extraction increased, and production was limited mostly to sectors relevant for the war effort. Repression increased, especially against the Jewish population.

After the Allied invasion of June 1944, the railroad strike and the frontline running through the Netherlands caused the Randstad to be cut off from food and fuel. That resulted in acute need and starvation, the Hongerwinter. The German authorities lost more and more control over the situation as the population tried to keep what little they had away from German confiscations and were less inclined to co-operate now that it was clear that Germany would lose the war. Some Nazis prepared to make a last stand against the Allied troops, followed Berlin's Nero Decree and destroyed goods and property (destructions of the Amsterdam and Rotterdam ports, inundations), but others tried to mediate the situation.

Luftwaffe

editThe Luftwaffe was especially interested in the Netherlands, as the country was designated to become the main area for the air force bases from which to attack the United Kingdom. The Germans started construction of ten major military air bases on the day after the formal Dutch surrender, 15 May 1940. Each of them was intended to have at least 2 or 3 hard surface runways, a dedicated railway connection, major built-up and heated repair and overhaul facilities, extensive indoor and outdoor storage spaces, and most had housing and facilities for 2,000 to 3,000 men. Each air base also had an auxiliary and often a decoy airfield, complete with mock-up planes made from plywood. The largest became Deelen Air Base, north of Arnhem (twelve former German buildings at Deelen are now national monuments). Adjacent to Deelen, the large central air control bunker for Belgium and the Netherlands, Diogenes, was set up.

Within a year, the attack strategy had to be altered to a defensive operation. The ensuing air war over the Netherlands cost almost 20,000 airmen (Allied and German) their lives and 6,000 planes went down over the country, an average of three per day during the five years of the war.

The Netherlands turned into the first line of western air defence for Germany and its industrial heartland of the Ruhrgebiet, complete with extensive flak, sound detection installations and later radar. The first German night-hunter squadron started its operations from the Netherlands.

Some 30,000 Luftwaffe men and women were involved in the Netherlands throughout the war.[25]

Forced labour and resistance

editThe Arbeitseinsatz, the drafting of civilians for forced labour, was imposed on the Netherlands. That obliged every man between 18 and 45 (530,000) to work in German factories, which were bombed regularly by the western Allies. Those who refused were forced into hiding. As food and many other goods were taken out of the Netherlands, rationing increased (with ration books). At times, the resistance would raid distribution centres to obtain ration cards to be distributed to those in hiding.

For the resistance to succeed, it was sometimes necessary for its members to feign collaboration with the Germans. After the war, that led to difficulties for those who pretended to collaborate when they could not prove they had been in the resistance, which was difficult because it was in the nature of the job to keep it a secret.

Atlantic Wall

editThe Atlantic Wall, a gigantic coastal defence line built by the Germans along the entire European coast from southwestern France to Denmark and Norway, included the coastline of the Netherlands. Some towns, such as Scheveningen, were evacuated because of that. In The Hague alone, 3,200 houses were demolished and 2,594 were dismantled. 20,000 houses were cleared, and 65,000 people were forced to move. The Arbeitseinsatz also included forcing the Dutch to work on these projects, but a form of passive resistance took place there with people working slowly or poorly.

Holocaust

editShortly after it was established, the military regime began to persecute the Jews of the Netherlands. In 1940, there were no deportations, and only small measures were taken against the Jews. In February 1941, the Nazis deported a small group of Dutch Jews to Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. The Dutch reacted with the February strike, a nationwide protest against the deportations, unique in the history of Nazi-occupied Europe. Although the strike did not accomplish much—its leaders were executed—it was an initial setback for Seyss-Inquart. He had intended both to deport the Jews and to win the Dutch over to the Nazi cause.[26]

Before the February strike, the Nazis had installed a Jewish Council (Dutch: Joodse Raad). This was a board of Jews, headed by Professor David Cohen and Abraham Asscher. Independent Jewish organisations, such as the Committee for Jewish Refugees—founded by Asscher and Cohen in 1933—were closed.[27] The Jewish Council ultimately served as an instrument for organising the identification and deportation of Jews more efficiently; the Jews on the council were told and convinced they were helping the Jews.[28]

In 1939 the Jewish population of the Netherlands was between 140,000 and 150,000, 24,000–34,000 of whom were refugees from Germany and German-controlled areas. That year, the Committee for Jewish Refugees established the Westerbork transit camp to process incoming refugees; in 1942 the German occupiers repurposed it to process outgoing Jews to labour and concentration camps. Over half of the total Jewish population—about 79,000—lived in Amsterdam; this number increased as Germans forcibly moved Dutch Jews into the city in preparation for mass deportation.

In May 1942, Jews were ordered to wear Star of David badges. The Catholic Church in the Netherlands publicly condemned the government's action in a letter read at all Sunday parish services. The Nazi government began to treat the Dutch more harshly, and notable socialists were imprisoned. Later in the war, Catholic priests, including Titus Brandsma, were deported to concentration camps.[28]

Concentration camps were built at Vught and Amersfoort as well. Eventually, with the assistance of Dutch police and civil service, the majority of the Dutch Jews were deported to concentration camps.[29]

Germany was particularly effective at deporting and killing Jews in the Netherlands. By 1945, the Dutch Jewish population was about a quarter of what it had been (about 35,000). Of that number, about 8,500 escaped deportation by being in a mixed marriage to a non-Jew; about 16,500 hid or otherwise evaded detection by German authorities; and 7,000–8,000 escaped the Netherlands for the duration of the occupation.

The Dutch survival rate of 27% is much lower than in neighbouring Belgium, where 60% of Jews survived, and France, where 75% survived.[30] Historians have offered several hypotheses for the low survival rate, including:

- The Netherlands included religion in its national records, which reduced the opportunity for Jews to mask their identity.

- Dutch authorities and the Dutch people were unusually co-operative with German authorities.

- The flat, unforested Dutch landscape deprived Jews of potential hiding places.

Marnix Croes and Peter Tammes examined the survival rates among the different regions of the Netherlands. They conclude that most of the hypotheses do not explain the data. They suggest that a more likely explanation was the varying "ferocity" with which the Germans and their Dutch collaborators hunted Jews in hiding in the different regions.[30] In 2002, Ad van Liempt published Kopgeld: Nederlandse premiejagers op zoek naar joden, 1943 (Bounty: Dutch bounty hunters in search of Jews, 1943), published in English as Hitler's Bounty Hunters: The Betrayal of the Jews (2005). He found in newly-declassified records that the Germans paid a bounty to police and other collaborators, such as the Colonnie Henneicke group, for tracking down Jews.[31]

A 2018 publication, De 102.000 namen, lists the 102,000 known victims of the persecution of Jewish, Sinti, and Roma people from the Netherlands; the book is published by Boom, Amsterdam, under the auspices of the Westerbork Remembrance Center.[32]

Collaboration

editMany Dutch men and women chose or were forced to collaborate with the German regime or joined the German armed forces, which usually would mean being placed in the Waffen-SS. Others, like members of the Henneicke Column, were actively involved in capturing hiding Jews for a price and delivering them to the German occupiers. It is estimated that the Henneicke Column captured around 8,000 to 9,000 Dutch Jews who were ultimately murdered in the German death camps.

The National Socialist Movement in the Netherlands was the only legal political party in the Netherlands from 1941 and was actively involved in collaboration with the German occupiers. In 1941, when Germany still seemed certain to win the war, about three per cent of the adult male population belonged to the NSB.

After the war broke out, the NSB sympathised with the Germans but nevertheless advocated strict neutrality for the Netherlands. In May 1940, after the German invasion, 10,000 NSB members and sympathizers were put in custody by the Dutch government. Soon after the Dutch defeat, on 14 May 1940, they were set free by German troops. In June 1940, NSB leader Anton Mussert held a speech in Lunteren in which he called for the Dutch to embrace the Germans and renounce the Dutch Monarchy, which had fled to London.

In 1940, the German regime had outlawed all socialist and communist parties. In 1941, it forbade all parties except for the NSB, which openly collaborated with the occupation forces. Its membership grew to about 100,000. The newcomers (meikevers, Cockchafers or Maybugs, where May refers to the month of the German invasion) were shunned by many existing members, who accused them of opportunist behaviour. The NSB played an important role in lower government and civil service. Every new mayor appointed by the German occupation government was a member of the NSB. However, for most higher functions, the Germans preferred to leave the existing elite in place since they knew that the NSB neither offered enough suitable candidates nor enjoyed enough popular support.

After the German signing of surrender on 6 May 1945, the NSB was outlawed. Mussert was arrested the following day, and was executed on 7 May 1946. Many members of the NSB were arrested, but few were convicted.

In September 1940, the Nederlandsche SS was formed as "Afdeling XI" (Department XI) of the NSB. It was the equivalent to the Allgemeine SS in Germany. In November 1942, its name was changed to Germaansche SS in Nederland. The Nederlandsche SS was primarily a political formation but also served as manpower reservoir for the Waffen-SS.

Between 22,000 and 25,000 Dutchmen volunteered to serve in the Waffen-SS.[33] The most notable formations were the 4th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Brigade Nederland which saw action exclusively on the Eastern Front and the SS Volunteer Grenadier Brigade Landstorm Nederland which fought in Belgium and the Netherlands.[34]

The Nederland brigade participated in fighting on the Eastern Front during the Battle of Narva, with several soldiers receiving the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross, Nazi Germany's highest award for bravery.

Another form of collusion was providing goods and services essential to the German war efforts. Especially in 1940 and 1941, when a German victory was still a possibility, Dutch companies were willing to provide such goods to the greedily-purchasing Germans. Strategic supplies fell in German hands, and in May 1940 German officers placed their first orders with Dutch shipyards. The co-operation with the German industry was facilitated by the fact that due to the occupation the German market 'opened' and due to facilitating behaviour from the side of the partly pro-German elite. Many directors justified their behaviour with the argument that otherwise, the Germans would have closed down their company or would have replaced them with NSB members and so they could still exercise some limited influence. After the war, no heavy sentences were dealt to high officials and company directors.

Dutch resistance

editThe Dutch resistance to the Nazi occupation during World War II developed relatively slowly, but its counterintelligence, domestic sabotage, and communications networks provided key support to Allied forces beginning in 1944 and through the liberation of the country. Discovery by the Germans of involvement in the resistance meant an immediate death sentence.

The country's terrain, lack of wilderness and dense population made it difficult to conceal any illicit activities, and it was bordered by German-controlled territory, which offered no escape route except by sea. Resistance in the Netherlands took the form of small-scale decentralised cells engaged in independent activities. The Communist Party of the Netherlands, however, organised resistance from the start of the war, as did the circle of liberal democratic resisters who were linked through Professor Dr. Willem or Wim Schermerhorn to the Dutch government-in-exile in London, the LKP ("Nationale Knokploeg", or National Force Units, literal translation "Brawl Crew"). This was one of the largest resistance groups, numbering around 550 active participants; it was also heavily targeted by Nazi intelligence for destruction due to its links with the United Kingdom. Some small groups had absolutely no links to others. These groups produced forged ration cards and counterfeit money, collected intelligence, published underground newspapers, sabotaged phone lines and railways, prepared maps, and distributed food and goods. After 1942 the National Organisation (LO) and National Force Units (LKP) organised national coordination. Some contact was established with the government in London. After D-day the existing national organisations, the LKP, the OD and the Council of Resistance merged into the internal forces under the command of Prince Bernhard.[35]

One of the riskiest activities was hiding and sheltering refugees and enemies of the Nazi regime, Jewish families, underground operatives, draft-age Dutch, and others. Collectively these people were known as onderduikers ('under-divers'). Later in the war, this system of people-hiding was also used to protect downed Allied airmen. Reportedly, resistance doctors in Heerlen concealed an entire hospital floor from German troops.[36]

In February 1943, a Dutch resistance cell rang the doorbell of the former head of the Dutch general staff and now-collaborating Lieutenant general Hendrik Seyffardt in the Hague. Seyffardt commanded the campaign to recruit Dutch volunteers for the Waffen-SS and the German war effort on the Eastern Front. After he answered and identified himself, he was shot twice and died the following day. The assassination of the high-level official triggered a harsh reprisal from SS General Hanns Albin Rauter, who ordered the killing of 50 Dutch hostages and a series of raids on Dutch universities. On October 1 and 2, 1944, the Dutch resistance attacked German troops near the village of Putten, which resulted in war crimes on behalf of the occupying Germans. After the attack, part of the town was destroyed, and seven people were shot in the Putten raid. The entire male population of Putten was deported and most were subjected to forced labour; 48 out of 552 survived the camps. The Dutch resistance attacked Rauter's car on March 6, 1945, unaware of the identity of its occupant, which in turn led to the killings at Woeste Hoeve, where 116 men were rounded up and executed at the site of the ambush and another 147 Gestapo prisoners executed elsewhere.[37]

Dutch government and army in exile

editThe Dutch army's successful resistance in the Battle for The Hague gave the royal family an opportunity to escape. Several days before the surrender, Princess Juliana, Prince Bernhard and their daughters (Princess Beatrix and Princess Irene) travelled from The Hague to London. On 13 May, Queen Wilhelmina and key members of the Dutch government followed. The royal family were guests at Buckingham Palace, where Irene was christened on 31 May. Juliana later took Beatrix and Irene to Canada, where they remained for the duration of the war.[38]

Shortly after the German victory, the Dutch government, led by Prime Minister Dirk Jan de Geer, was invited by the Germans to return to the country and to form a pro-German puppet government, as the Vichy government had agreed to do in France. De Geer wanted to accept that invitation, but the Queen refused it and dismissed him in favour of Pieter Gerbrandy.[citation needed]

Dutch East Indies and war in the Far East

editOn 8 December 1941, the Netherlands declared war on the Japanese Empire.[39] On 10 January 1942, the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).

Dutch naval ships joined forces with the Allies to form the American-British-Dutch-Australian (ABDA) Fleet, commanded by Dutch Rear Admiral Karel Doorman. On February 27–28, 1942, Doorman was ordered to take the offensive against the Imperial Japanese Navy. His objections on the matter were overruled. The ABDA fleet finally encountered the Japanese surface fleet at the Battle of the Java Sea at which Doorman gave the order to engage. During the ensuing battle, the Allied fleet suffered heavy losses. The Dutch cruisers Java and De Ruyter were lost, together with the destroyer Kortenaer. The other Allied cruisers, the Australian Perth, the British Exeter, and the American Houston, tried to disengage but were spotted by the Japanese in the following days and were eventually all destroyed. Many ABDA destroyers were also lost.[40]

After Japanese troops had landed on Java, and the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army had been unsuccessful in stopping their advance because the Japanese could not occupy a relatively-unguarded airstrip [clarfiy], the Dutch forces on Java surrendered on 7 March 1942. Some 42,000 Dutch soldiers were taken prisoner and interned in labour camps, but some were executed on the spot. Later, all Dutch civilians (some 100,000 in total), were arrested and interned in camps, and some were deported to Japan or sent to work on the Thai-Burma Railway. During the Japanese occupation, between 4 and 10 million Javanese were forced to work for the Japanese war effort. Some 270,000 Javanese were taken to other parts of Southeast Asia; only 52,000 of those survived.

A Dutch government study described how the Japanese military forcibly recruited women as prostitutes in the Dutch East Indies[41] and concluded that among the 200 to 300 European women working in Japanese military brothels, "some sixty five were most certainly forced into prostitution".[42] Others, faced with starvation in the refugee camps, agreed to offers of food and payment for work, the nature of which was not completely revealed to them.[43][44][45][46][47]

The Dutch submarines escaped and resumed the war effort from bases in Australia such as Fremantle. As a part of the Allied forces, they were on the hunt for Japanese tankers on their way to Japan and the movement of Japanese troops and weapons to other sites of battle, including New Guinea. Because of the significant number of Dutch submarines active in the Pacific Theatre of the war, the Dutch were named the "Fourth Ally" in the theatre, along with the Australians, the Americans, and the New Zealanders.

Many Dutch Army and Navy airmen escaped and, with aeroplanes provided by the Americans, formed the Royal Australian Air Force's Nos. 18 and 120 (Netherlands East Indies) Squadrons, equipped with B-25 Mitchell bombers and P-40 Kittyhawk fighters, respectively. No. 18 Squadron conducted bombing raids from Australia to the Dutch East Indies. Both squadrons eventually also participated in their recapture.

Gradually, control of the Netherlands East Indies was wrested away from the Japanese. The largest Allied invasion of the Pacific Theatre took place in July 1945 with Australian landings on the island of Borneo to seize the strategic oil-fields from the Japanese forces, which were now cut off. At the time, the Japanese had already begun independence negotiations with Indonesian nationalists such as Sukarno, and Indonesian forces had taken control of sizeable portions of Sumatra and Java. After the Japanese surrender on 15 August 1945, Indonesian nationalists, led by Sukarno declared Indonesian independence, and a four-year armed and diplomatic struggle between the Netherlands and the Indonesian nationalists began.

Dutch civilians, who suffered greatly during their internment, finally returned home to a land that had greatly suffered as well.[48]

Final year

editAfter the Allied landing in Normandy in June 1944, the Western Allies rapidly advanced in the direction of the Dutch border. Tuesday, 5 September, is known as Dolle dinsdag ("Mad Tuesday") since the Dutch began celebrating and believed that they were close to liberation. In September, the Allies launched Operation Market Garden, a failed attempt to advance from the Dutch-Belgian border across the rivers Meuse, Waal and Rhine into the north of the Netherlands and Germany. However, the Allied forces did not reach the objective because they could not capture the Rhine bridge at the Battle of Arnhem. During Market Garden, substantial regions to the south were liberated, including Nijmegen and Eindhoven. A subsequent German counterattack against the Nijmegen salient (the Island) was defeated in early October.

Parts of the southern Netherlands were not liberated by Operation Market Garden, which had established a narrow salient between Eindhoven and Nijmegen. In the east of North Brabant and in Limburg, British and American forces during Operation Aintree managed to defeat the remaining German forces west of the Meuse between late September and early December 1944 by destroying the German bridgehead between the Meuse and the Peel marshes. During the offensive, the only tank battle ever fought on Dutch soil took place at Overloon.

At the same time, the Allies also advanced into the province of Zeeland. At the start of October 1944, the Germans still occupied Walcheren and dominated the Scheldt estuary and its approaches to the port of Antwerp. The crushing need for a large supply port forced the Battle of the Scheldt in which First Canadian Army fought on both sides of the estuary during the month to clear the waterways. Large battles were fought to clear the Breskens Pocket, Woensdrecht and the Zuid-Beveland Peninsula of German forces, primarily "stomach" units of the Wehrmacht as well as German paratroopers of Battle Group Chill. German units composed of convalescents and the medically unfit were named for their ailment; thus, "stomach" units for soldiers with ulcers.[49]

By 31 October, resistance south of the Scheldt had collapsed, and the Canadian 2nd Infantry Division, British 52nd (Lowland) Division and 4th Special Service Brigade all made attacks on Walcheren Island. Strong German defences made a landing very difficult, and the Allies responded by bombing the dikes of Walcheren at Westkapelle, Vlissingen and Veere to flood the island. Though the Allies had warned residents with pamphlets, 180 inhabitants of Westkappelle died. The coastal guns on Walcheren were silenced in the opening days of November and the Scheldt battle declared over. No German forces remained intact along the 64 mi (103 km) path to Antwerp.

After the offensive on the Scheldt, Operation Pheasant was launched in conjunction to liberate North Brabant. The offensive after some resistance liberated most of region; the cities of Tilburg, 's-Hertogenbosch, Willemstad and Roosendaal were liberated by British forces. Bergen Op Zoom was taken by the Canadians and the Polish 1st Armoured Division led by General Maczek liberated the city of Breda without any civilian casualties on 29 October 1944. The operation as a whole also broke the German positions that had defended the region along its canals and rivers.

The Dutch government had not wanted to use the old water line when the Germans had invaded in 1940. It was still possible to create an island out of the Holland region by destroying dikes and flooding the polders, which contained the main cities. The Dutch government had decided that too many people would die to justify the flooding. However, Hitler ordered for Fortress Holland (German: Festung Holland) to be held at any price. Much of the northern Netherlands remained in German hands until the Rhine crossings in late March 1945.

Hunger Winter

editThe winter of 1944–1945 was very harsh, which led to "hunger journeys" and many cases of starvation (about 30,000 casualties), exhaustion, cold and disease. The winter is known as the Hongerwinter (literally, "hunger winter") or the Dutch famine of 1944. In response to a general railway strike ordered by the Dutch government-in-exile in expectation of a general German collapse near the end of 1944, the Germans cut off all food and fuel shipments to the western provinces in which 4.5 million people lived. Severe malnutrition was common and 18,000 people starved to death. Relief came at the beginning of May 1945.[50]

Bombing of the Bezuidenhout

editOn 3 March 1945, the British Royal Air Force mistakenly bombed the densely populated Bezuidenhout neighbourhood in the Dutch city of The Hague. The British bomber crews had intended to bomb the Haagse Bos ("Forest of the Hague") district where the Germans had installed V-2 launching facilities that had been used to attack English cities. However, the pilots were issued with the wrong coordinates, so the navigational instruments of the bombers had been set incorrectly. Combined with fog and clouds which obscured their vision, the bombs were instead dropped on the Bezuidenhout residential neighbourhood. At the time, the neighbourhood was more densely populated than usual with evacuees from The Hague and Wassenaar; 511 residents were killed and approximately 30,000 were left homeless.

Liberation

editAfter crossing the Rhine at Wesel and Rees, Canadian, British and Polish forces entered the Netherlands from the east and liberated the eastern and the northern provinces. Notable battles during the movement are the Battle of Groningen and the Battle of Otterlo, both in April 1945.

The western provinces were not liberated until the surrender of German forces in the Netherlands was negotiated on the eve of 5 May 1945 (three days before the general capitulation of Germany), in the Hotel de Wereld in Wageningen. Previously the Swedish Red Cross had been allowed to provide relief efforts, and Allied forces were allowed to airdrop food over the German-occupied territories in Operation Manna.[51]

During Operation Amherst, Allied troops advanced to the North Netherlands. To support the advance of the II Canadian Corps, French paratroopers were dropped in Friesland and Drenthe who were the first Allied troops to reach Friesland. The French successfully captured the crucial Stokersverlaat Bridge. The region was successfully liberated shortly after.[52]

On the island of Texel, nearly 800 men of the Georgian Legion, serving in the German army as Osttruppen, rebelled on 5 April 1945. Their rebellion was crushed by the German army after two weeks of battle. 565 Georgians, 120 inhabitants of Texel, and 800 Germans died. The 228 surviving Georgians were forcibly repatriated to the Soviet Union when the war ended.

After being liberated, Dutch citizens began taking the law into their own hands, like in other liberated countries, such as France. Collaborators and Dutch women who had relationships with men of the German occupying force, called "Moffenmeiden" were abused and humiliated in public, usually by having their heads shaved and painted orange.[citation needed]

Casualties

editBy the end of the war, 205,901 Dutch men, women and children had died of war-related causes. The Netherlands had the highest per capita death rate of all Nazi-occupied countries in Western Europe (2.36%).[53] Over half (107,000) were Holocaust victims. There were also many thousands of non-Dutch Jews in the total, who had fled to the Netherlands from other countries, seeking safety, the most famous being Anne Frank. Another 30,000 died in the Dutch East Indies, either while fighting the Japanese or in camps as Japanese POWs. Dutch civilians were also held in these camps.[54]

Postwar

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

After the war, some accused of collaborating with the Germans were lynched or otherwise punished without trial. Men who had fought with the Germans in the Wehrmacht or Waffen-SS were used to clear minefields and suffered losses accordingly. Others were sentenced by courts for treason. Some were proven to have been wrongly arrested and were cleared of charges, sometimes after they had been held in custody for a long period of time.

The Dutch government initially developed plans to annex part of Germany (the Bakker-Schut Plan), which would substantially increase the country's land area. The German population would be expelled or "Dutchified". The plan was dropped after an Allied refusal. Two small villages were added to the Netherlands in 1949 and returned in 1963. One successfully-implemented plan was Operation Black Tulip, the deportation of all holders of German passports from the Netherlands, numbering several thousand.

The bank balances of Dutch Jews who were killed were still the subject of legal proceedings more than 70 years after the end of the war.[citation needed]

The end of the war also meant the final loss of the Dutch East Indies. After the surrender of the Japanese in the Dutch East Indies, Indonesian nationalists fought a four-year war of independence against Dutch and at first British Commonwealth forces, which eventually led to the Dutch recognition of the independence of Indonesia under pressure of the United States. Many Dutch and Indonesians then emigrated or returned to the Netherlands.

World War II left many lasting effects on Dutch society. On 4 May, the Dutch commemorate those who died during the war, and all wars since. Among the living, there are many who still bear the emotional scars of the war from both the first and the second generation. In 2000, the government was still granting 24,000 people an annual compensatory payment although that also includes victims from later wars, such as the Korean War.

In 2017, the Dutch Red Cross offered its “deep apologies” for its failure to act to protect Jews, Sinti, Roma, and political prisoners during the war after the publication of a study that it had commissioned from the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.[55][56]

See also

edit- Netherlands in World War I

- Chronological overview of the liberation of Dutch cities and towns during World War II

- Dutch resistance

- Englandspiel

- List of Dutch military equipment of World War II

- Military history of the Netherlands during World War II

- Corrie ten Boom

- Jan de Hartog

- Philip Slier

- Maurice Frankenhuis

- Canada-Netherlands relations

- Liberation Day (Netherlands)

References

edit- ^ Werner Warmbrunn (1963). The Dutch Under German Occupation, 1940–1945. Stanford UP. pp. 5–7. ISBN 9780804701525.

- ^ Loyd E. Lee and Robin D. S. Higham, ed. (1997). World War II in Europe, Africa, and the Americas, with General Sources: A Handbook of Literature and Research. Greenwood. p. 277. ISBN 9780313293252.

- ^ Croes, Marnix (Winter 2006). "The Holocaust in the Netherlands and the Rate of Jewish Survival'" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 20 (3). Research and Documentation Center of the Netherlands Ministry of Justice: 474–499. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcl022. S2CID 37573804.

- ^ Tim Cole, Review: Hitler's Bounty Hunters: The Betrayal of the Jews, English Historical Review, Volume CXXI, Issue 494, 1 December 2006, pp. 1562–1563, doi:10.1093/ehr/cel364

- ^ a b c d e "The Netherlands between the Wars, 1929–1940". History of the Netherlands. World History at KLMA. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Hansen, Erik (1981). "Fascism and Nazism in the Netherlands, 1929–39". European Studies Review. 11 (3): 33–385. doi:10.1177/026569148101100304. S2CID 144805335.

- ^ a b TC-32 (6 October 1939). "Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression". Vol. I. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Abbenhuis, Maartje M. (2006). The Art of Staying Neutral: The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914–1918. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 13–21. ISBN 90-5356-818-2.

- ^ Hirschfeld, Gerhard (1988). Nazi Rule and Dutch Collaboration: The Netherlands under German Occupation, 1940–1945 (1st English ed.). Oxford: Berg. pp. 12–14. ISBN 0-85496-146-1.

- ^ a b c Wubs, Ben (2008). International Business and War Interests: Unilever between Reich and Empire, 1939–45. London: Routledge. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-415-41667-2.

- ^ a b c d "Dutch Army Strategy and Armament in WWII". Waroverholland.nl. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "The Germans attack in the West". World War 2 Today. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Amersfoort, Herman; Kamphuis, Piet, eds. (2005), Mei 1940 – De Strijd op Nederlands grondgebied (in Dutch), Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers, p. 64, ISBN 90-12-08959-X

- ^ "Dutch Armoured Cars type Landsverk". Waroverholland.nl. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ "Battle of the Netherlands". Totally History. 12 June 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ a b "Capitulation". Waroverholland.nl. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Amersfoort, Herman; Kamphuis, Piet, eds. (2005), Mei 1940 – De Strijd op Nederlands grondgebied, Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers, p. 192, ISBN 90-12-08959-X

- ^ Various. Belgium: The Official Account of What Happened, 1939–40. London: Belgian Ministry for Foreign Affairs. pp. 32–36.

- ^ a b c Teeuwisse, Joeri (17 March 2006). "Life During The Dutch Occupation – Part 2: May 1940, The Battle For The Netherlands". Armchair General. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f "May 14 – Rotterdam". Waroverholland.nl. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Ashton, H.S. (1941). The Netherlands at War. London. pp. 24–25.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "The Royal Dutch Navy". Waroverholland.nl. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Richard Z. Chesnoff (2011). Pack of Thieves: How Hitler and Europe Plundered the Jews and Committed the Greatest Theft in His. Knopf Doubleday. p. 103. ISBN 9780307766946.

- ^ Samuel P. Oliner (1992). Altruistic Personality: Rescuers of Jews in Nazi Europe. Simon and Schuster. p. 33. ISBN 9781439105382.

- ^ Vliegvelden in Oorlogstijd, Netherlands Institute for Military History (NIMH), The Hague 2009

- ^ Presser, Jacob (1988). Ashes in the Wind: the Destruction of Dutch Jewry. Arnold Pomerans (translation). Wayne State University Press (reprint of 1968 translated edition). ISBN 9780814320365. OCLC 17551064. [page needed]

- ^ Wasserstein, Bernard (2014). The Ambiguity of Virtue: Gertrude van Tijn and the Fate of the Dutch Jews. Harvard University Press. pp. 98–100. ISBN 9780674281387. OCLC 861478330.

- ^ a b Rozett, Robert; Spector, Shmuel (2013). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Taylor and Francis. p. 119. ISBN 9781135969509. OCLC 869091747.

- ^ Stone, Dan (2010). Histories of the Holocaust. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-956680-8.

- ^ a b Croes, Marnix (Winter 2006). "The Holocaust in the Netherlands and the Rate of Jewish Survival" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 20 (3): 474–499. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcl022. S2CID 37573804.

- ^ Tim Cole, Review: Hitler's Bounty Hunters: The Betrayal of the Jews, English Historical Review, Volume CXXI, Issue 494, 1 December 2006, pp. 1562–1563, doi:10.1093/ehr/cel364

- ^ De 102.000 namen; Amsterdam: Boom, 2018. ISBN 9789024419739. Reviewed in "De 102.000 Namen – Boek met alle namen vermoorde Joden, Sinti en Roma". Historiek.nl (in Dutch). 26 January 2018. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Waffen-SS (in numbers)". www.niod.nl. Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ Georg Tessin, Verbände und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS 1939–1945, Biblio Verlag, vol. 2 for Nederland, vol. 14 for Landstorm Nederland

- ^ Abraham J. Edelheit and Hershel Edelheit, History of the Holocaust: a handbook and dictionary (1994) p. 411

- ^ Mark Zuehlke, On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands, (2010) p. 187

- ^ Van der Zee, Henri A. (1998). The hunger Winter: Occupied Holland, 1944–1945 (1st ed.). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. p. 182. ISBN 0-8032-9618-5.

- ^ Janet Davison (April 29, 2013). "Abdicating Dutch queen was a wartime Ottawa schoolgirl". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ "The Kingdom of the Netherlands Declares War with Japan". ibiblio. Retrieved 2009-10-05.

- ^ L. Klemen, Forgotten Campaign. The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942 (1999).

- ^ Ministerie van Buitenlandse zaken 1994, pp. 6–9, 11, 13–14

- ^ "Digital Museum: The Comfort Women Issue and the Asian Women's Fund".

- ^ Soh, Chunghee Sarah. "Japan's 'Comfort Women'". International Institute for Asian Studies. Archived from the original on 2013-11-06. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ Soh, Chunghee Sarah (2008). The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan. University of Chicago Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-226-76777-2.

- ^ "Women made to become comfort women – Netherlands". Asian Women's Fund.

- ^ Poelgeest. Bart van, 1993, Gedwongen prostitutie van Nederlandse vrouwen in voormalig Nederlands-Indië 's-Gravenhage: Sdu Uitgeverij Plantijnstraat. [Tweede Kamer, vergaderjaar 93-1994, 23 607, nr. 1.]

- ^ Poelgeest, Bart van. "Report of a study of Dutch government documents on the forced prostitution of Dutch women in the Dutch East Indies during the Japanese occupation." [Unofficial Translation, January 24, 1994.]

- ^ Twomey, Christina (2009). "Double Displacement: Western Women's Return Home from Japanese Internment in the Second World War". Gender and History. 21 (3): 670–684. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0424.2009.01566.x. S2CID 143970869.

- ^ Ryan, Cornelius (1995). A Bridge Too Far (First paperback ed.). New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 26, 39. ISBN 0-684-80330-5.

- ^ Banning, C. (1946). "Food Shortage and Public Health, First Half of 1945". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 245 (The Netherlands during German Occupation): 93–110. doi:10.1177/000271624624500114. JSTOR 1024809. S2CID 145169282.

- ^ Goddard, Lance (2005). Canada and the liberation of the Netherlands, May 1945. Toronto: Dundurn Group. ISBN 1-55002-547-3.

- ^ Boersma, Bauke (29 February 2020). "Met Franse para's begon bevrijding van Fryslân". Friesch Dagblad.

- ^ See World War II casualties

- ^ See World War II casualties#endnote Indonesia

- ^ "Diepe verontschuldigingen' van Rode Kruis" [Deep apologies of the Red Cross]. De Telegraaf (in Dutch). 2017-11-01. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

- ^ "Dutch Red Cross apologizes for failing Jews in WWII". The Times of Israel. AFP. 1 November 2017. Retrieved 2018-10-14.

Sources

edit- Ministerie van Buitenlandse zaken (January 24, 1994). "Gedwongen prostitutie van Nederlandse vrouwen in voormalig Nederlands-Indië [Enforced prostitution of Dutch women in the former Dutch East Indies]". Handelingen Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal [Hansard Dutch Lower House] (in Dutch). 23607 (1). ISSN 0921-7371. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

Further reading

edit- Bijvoet, Tom and Van Arragon Hutten, Anne. The Dutch in Wartime, Survivors Remember (Mokeham Publishing, Oakville, Ontario 2011–2017) The Dutch in Wartime

- Croes, Marnix (Winter 2006). "The Holocaust in the Netherlands and the Rate of Jewish Survival'" (PDF). Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 20 (3). Research and Documentation Center of the Netherlands Ministry of Justice: 474–499. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcl022. S2CID 37573804.

- De Zwarte, Ingrid. The Hunger Winter: Fighting Famine in the Occupied Netherlands, 1944–1945 (Cambridge University Press, 2020) online.

- Dewulf, Jeroen. Spirit of Resistance: Dutch Clandestine Literature during the Nazi Occupation (Rochester NY: Camden House 2010)

- Diederichs, Monika. "Stigma and Silence: Dutch Women, German Soldiers and their children", in Kjersti Ericsson and Eva Simonsen, eds. Children of World War II: The Hidden Enemy Legacy (Oxford U.P. 2005), 151–64.

- Foot, Michael, ed. Holland at war against Hitler: Anglo-Dutch relations 1940–1945 (1990) excerpt and text search

- Foray, Jennifer L. "The 'Clean Wehrmacht' in the German-occupied Netherlands, 1940–5," Journal of Contemporary History 2010 45:768–787 doi:10.1177/0022009410375178

- Friedhoff, Herman. Requiem for the Resistance: The Civilian Struggle Against Nazism in Holland and Germany (1989)

- Goddard, Lance. Canada and the liberation of the Netherlands, May 1945 (2005)

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard. Nazi Rule and Dutch Collaboration: The Netherlands under German Occupation 1940–1945 (Oxford U.P., 1998)

- Hirschfeld, Gerhard. "Collaboration and Attentism in the Netherlands 1940–41," Journal of Contemporary History (1981) 16#3 pp 467–486. Focus on the "Netherlands Union" active in 1940–41 in JSTOR

- Hitchcock, William I. The Bitter Road to Freedom: The Human Cost of Allied Victory in World War II Europe (2009) ch 3 is "Hunger: The Netherlands and the Politics of Food," pp 98–129

- Maas, Walter B. The Netherlands at war: 1940–1945 (1970)

- Mark, Chris (1997). Schepen van de Koninklijke Marine in W.O. II. Alkmaar: De Alk b.v. ISBN 9789060135228.

- Moore, Bob. " Occupation, Collaboration and Resistance: Some Recent Publications on the Netherlands During the Second World War," European History Quarterly (1991) 211 pp 109–118. Online at Sage

- Sellin, Thorsten, ed. "The Netherlands during German Occupation," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science Vol. 245, May, 1946 pp i–180 in JSTOR, 18 essays by experts; focus on home front economics, society, Resistance, Jews

- van der Zee, Henri A. The hunger winter: occupied Holland, 1944–1945 (U of Nebraska Press, 1998) excerpt and text search

- Warmbrunn, Werner. The Dutch under German Occupation 1940–1945 (Stanford U.P. 1963)

- Zuehlke, Mark. On to Victory: The Canadian Liberation of the Netherlands, March 23 – May 5, 1945 (D & M Publishers, 2010.)

External links

edit- Canada and Holland The liberation of the Netherlands with photos and video footage.

- Canadian Newspapers and the Second World War – The Liberation of the Netherlands, 1944–1945

- Administrators of the German occupied Netherlands during WW II at the Wayback Machine (archived January 24, 2004)

- The invasion of the Netherlands in 1940

- Dutch Resistance Museum

- World War II: Dutch aftermath and recovery

- Beeldbankwo2 (Photobank WWII), a project led by the Dutch National Archives

- De Oorlog – A NPS Documentary series about World War II and the Netherlands

- The Dutch in Wartime, survivors remember – Dutch immigrants to Canada and the USA share their memories of war and occupation

- Liberation of the Netherlands