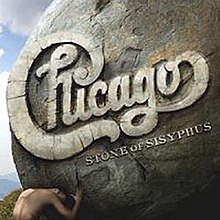

Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus is the twenty-first studio album, and thirty-second overall, by Chicago. Often referred to as their "lost" album, it was recorded in 1993 and originally intended to be released as Stone of Sisyphus on March 22, 1994, as their eighteenth studio album and twenty-second total album. However, the album was unexpectedly and controversially rejected by the record company, which reportedly contributed to Chicago's later decision to leave their services entirely. Even after the band acquired the rights to their catalog, the album remained unreleased until June 17, 2008, after a delay of fourteen years and ten more albums.[1]

| Stone of Sisyphus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 17 June 2008 | |||

| Recorded | 1993 | |||

| Genre | Rock | |||

| Length | 51:31 | |||

| Label | Rhino Records | |||

| Producer | Peter Wolf | |||

| Chicago chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus | ||||

| ||||

History

editBackground

editNo matter how prolific we are ... 'Hey man, that'll never get on the radio.'

With the releases of Chicago 18, Chicago 19, and Twenty 1, the band with its new generation of members had accomplished what vocalist and bassist Jason Scheff described as a "new legacy" for the 1990s. The next album, initially assumed to be called Chicago XXII, was conceived out of a desire to rediscover the band's personal, musical, and cultural roots, as an entity existing apart from its ultimately commercially marketed trappings. Scheff reflected, "In a sense, it was the beginning of that spirit ... of making music for the right reasons."[2]

Concluding their recent album series with producers David Foster, Chas Sandford, and Ron Nevison, the band reapproached Peter Wolf to be the producer of the album. Having already declined the band's employ in the distant past due to scheduling issues, he now accommodated.[3]: 70 He admonished them, "Don't try to write a hit. ... You have to have your love in mind, and a hit record might happen."[3]: 79 Scheff later reflected that Sisyphus "was our statement ... taking all the motives away from [the idea that], 'I've got to make a hit; I've got to use outside writers' material'".[2] Walter Parazaider called it "a record that had to be made."[3]: 71

Thus, against the distant backdrop of wildfires in and around Los Angeles,[3]: 86 collaboration ensued at the residential studio of producer Peter Wolf.

Production

editThe musical content of Stone of Sisyphus was reportedly developed in "complete secrecy" from the entire outside world including the record label, in order to emphasize the band's creative sovereignty.[3]: 83

"Sleeping in the Middle of the Bed" was one of the album's more uniquely styled and potentially commercially controversial tracks. Containing themes of early hip-hop and chants, it was inspired by the 1960s' precursors of rap music, as taken from the band's listening sessions of composer Robert Lamm's personal collection of old records by The Last Poets.[3]: 75–76 "Bigger Than Elvis" is an unusually personal ballad, nostalgically recalling Jason Scheff's childhood adulation and heartsickness resulting from his father Jerry Scheff's traveling career as Elvis Presley's bassist, as had been canonized in the television broadcast of Aloha from Hawaii Via Satellite. Peter Wolf and his wife Ina heard Scheff's stories and coauthored the song. As a surprise, Scheff solicited an isolated bass performance from his father on the song, and later presented the completed tribute song to his father as a gift.[3]: 77–79

"Twenty Years on the Sufferbus" was the original title of what eventually became the album's title track, originally composed by Dawayne Bailey as a demo song without lyrics during Chicago's 1989 tour.[3]: 81 According to Bailey, Lee Loughnane would go on to receive cowriting credits on the song for having promoted Bailey's demo to the other band members.[4] With the key word "sufferbus" already having been recently used on the 1992 album Sunrise on the Sufferbus by Masters of Reality,[5] and rejecting the lyrical draft of "I'm gonna send my love to the universe", the search for a similar sounding word ultimately also yielded an accompanying ancient mythos.[6] Robert Lamm's early suggestion was to title the album Resolve, in order to depart once again from the band's standard numerical nomenclature of Chicago XXII due to the band's collective idea of this album's significance.[6][7]

As the subject matter of the title track's lyrics solidified, the album was renamed and then finally planned for release as Stone of Sisyphus in the United States on March 22, 1994. After its completion, the band had every anticipation of the album's release and reception.[8]

Managerial reception

editRegardless of the secrecy during the album's development, Peter Wolf got an overwhelmingly positive reception for the album's overall sound and motivation, from the prevailing management at Warner Bros. when he delivered the final draft sometime between September and November 1993.[2][3]: 83

... it could not have gone better. Michael [Ostin, head of Warner Bros. A&R] listened to the tracks, he jumped up and down, he told me again and again, "Oh, my God, now that's a hit! I love that! That's a hit! God, what a killer record. It's gonna fly out the first week!"[3]: 83

— Peter Wolf, Producer of Chicago's Stone of Sisyphus

Warner Bros. created the album's artwork, depicting a likeness of the toiling mythical protagonist, Sisyphus.[7] Shirts were printed for the impending tour, though they confusingly contained references to the nonexistent title, Chicago XXII.

However, the book The Greatest Music Never Sold states that within one month from the album's initial delivery to A&R, the entire project was suddenly and unilaterally rejected. Regardless of the expected industry procedures, there was reportedly no strategic contact from the record company toward the band's management, and the label made no attempt at renegotiation, remixing, rerecording, or reassignment.[3]: 84

[Stone of Sisyphus] was a little too adventuresome, shall we say, for the label at the time. ... They were expecting another "If You Leave Me Now", "Hard to Say I'm Sorry". ... They asked us to go back and do it again and we said, "Sorry, this is where we're at."

— Chicago's cofounder and trombonist, Jimmy Pankow[9]

Though no explanation of this controversy might ever be given from the perspective of the record company, Jason Scheff later explained that Warner Bros. Records had endured a major internal reorganization near that time. The band and its producer said this event had suddenly injected Warner Bros. with new management personnel who doubted the album's future sales performance against the company's requirements. Scheff explained that "the record label wasn't thrilled with the fact that they weren't involved ... during the making of it, plus a lot of political stuff was going on, where Warner Bros. was going through a big change, and letting some of their top executives go."[2][10]

Fallout

editProducer Peter Wolf rebuked the record company's unforeseen abrupt edict as being "only about politics and greed ... nothing to do with the talent"[9] and that it was "purely a business decision".[3]: 86

According to author Dan Leroy, "everyone involved" found it "devastating"; Wolf says he was "flabbergasted"; and Dawayne Bailey says, "[a] part of me died". The label's rejection cascaded down to contribute to a "schism within the band". These issues then directed the decisions of the band's own management, which in turn fueled controversy within the band. Management's acquiescence to the label's position, then coerced the same from most of the band's remaining founding members. Those members' yielding position contrasted with other members who nevertheless remained "determined to fight for Chicago's artistic freedom".[3]: 84

With the album representing the delivery of Bailey's first formal compositions and studio recordings with Chicago and yielding a personal epic in the form of Sisyphus,[3]: 80–83 [11] his contract with the band was not renewed, thus yielding a position for guitarist Keith Howland.

Leaving the completed Stone of Sisyphus in a yet unreleased status, the band's new trend of revitalized artistic output would nevertheless continue, instead releasing 1995's Night & Day: Big Band to a peak position of #90 on America's Billboard 200.[12][13]

The combination of the overarching philosophical and commercial divergence with Warner Bros., the band's new struggle to renegotiate its copyrights over its extensive classic catalog,[citation needed] and the fact that Sisyphus would have been the final album on the band's contract,[3]: 86 all culminated in a severance between Chicago and Warner Bros. in favor of Rhino Records and then ultimately in favor of independent publishing.

Later, the band's managerial failure to issue an official press release regarding the unreleased aftermath of Sisyphus and the subsequent departure of Bailey, left fans to years of rampant debate and conjecture. Through its official website, as well as public discussion forums of past and present band members, the band's organization actively worked to quell discussion and debate about Stone of Sisyphus,[citation needed] while sporadically releasing thematic and compilation albums.

Finally, the album was officially released as Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus on June 17, 2008, following fifteen years and ten albums after its completion.

[Presenting to the record label the new style that is Sisyphus] was laughable to these suits, because [they said], "Oh no, no, no, that's not Chicago!" And so we're up against this image thing, and no matter how prolific we are, in terms of up-tempo songs, it's like they don't trust it. Our manager comes to us and says, "Hey man, that'll never get on the radio. We know programmers, our A&R guy in the office couldn't shop that song no matter what he did."

— Jimmy Pankow, on Chicago's history of creative struggle in the modern era as of 1999[14]

[The mythological] Sisyphus believed he could tackle that rock one more time ... and that's the kind of faith you have to have in yourself and your work.

— composer, guitarist, lyricist, and vocalist on Chicago's Stone of Sisyphus, Dawayne Bailey[3]: 89

Release

editPost-1994

editStone of Sisyphus acquired a legendary status among superstar unreleased albums, such as Smile by The Beach Boys and Chinese Democracy by Guns N' Roses. Tracks from the unreleased album surfaced on bootleg recordings which were distributed via tape and the Internet,[3]: 88 and many of the songs appeared on albums from the various constituent artists, and from Chicago's own legitimate compilations.

To preview the upcoming Sisyphus album, the band performed "The Pull" in a live concert on July 9, 1993, released on the video album Chicago: In Concert at Greek Theatre.[15] The title song and "Bigger Than Elvis" were first released in Canada on the 1995 double CD compilation Overtime (Astral Music). A single edit of "Let's Take A Lifetime" debuted in Europe on the 1996 Arcade Records compilation called The Very Best Of Chicago (a title which would be reused in North America in 2002).

Five of the 12 tracks were released in Japan between 1997 and 1998 on the very rare green and gold editions of The Heart of Chicago compilations: "All the Years" (debut), "Bigger Than Elvis", and "Sleeping in the Middle of the Bed Again" (debut) all appear on the green-clad The Heart of Chicago 1967-1981, Volume II (Teichiku, 1997), with "The Pull" and "Here with Me (A Candle for the Dark)" appearing on the gold-clad The Heart of Chicago 1982-1998, Volume II (WEA Japan, 1998).

In 2003, three tracks from Stone of Sisyphus — "All the Years", "Stone of Sisyphus", and "Bigger Than Elvis" — were officially released in the United States on The Box by Rhino Records.[16]

In 2007, the album became a chapter in the book The Greatest Music Never Sold: Secrets of Legendary Lost Albums.[3]

Solo versions

editKeyboardist Robert Lamm previously recorded a solo version of "All the Years" in the early 1990s for his 1993 solo album Life Is Good in My Neighborhood (initially released in Japan by Reprise Records in 1993, it was released in 1995 in the US by Chicago's then label Chicago Records), and a version of "Sleeping in the Middle of the Bed (Again)" for his 1999 album In My Head.

Keyboard player and guitarist Bill Champlin recorded "Proud of Our Blindness", which was a slightly different lyrical version of "Cry for the Lost", for his 1995 solo album Through It All, whose liner notes included his personal criticism of the major record labels inspired by the controversy of Stone of Sisyphus.

Bassist Jason Scheff recorded a solo version of "Mah-Jong" for his 1997 solo album Chauncy.

2008 final release

editIn June 2008, Rhino Records released Stone of Sisyphus with four bonus songs. Officially, the album received the number "XXXII" in the band's album count (following Chicago XXX and The Best of Chicago: 40th Anniversary Edition). In various catalogs, it has been referenced as Chicago XXX II: Stone of Sisyphus or Stone of Sisyphus: XXXII. One of the songs intended for the 1994 release, "Get on This" (written by Dawayne Bailey, James Pankow, and Walter Parazaider's daughter Felicia), was not included in the 2008 release. No reason for this omission was given by Chicago or Rhino Records.

Reception

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [1] |

| Pittsburgh Post-Gazette | [17] |

| Glide Magazine | [18] |

| Deseret News | [13] |

Doug Collette of Glide Magazine gave 11 stars out of 11 for the album's "wealth of ideas". He declared that "anyone who remembers the invigorating sound of the original Chicago will find Stone of Sisyphus wholly comparable, if perhaps not its complete equal".[18] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic.com gave it 2.5 stars out of 5, saying "judged alongside Chicago's other albums it's flat-out bizarre".[1] Scott Nowlin of the Deseret News gave three out of four stars, describing it as "well-written, well-produced, and fun to hear".[13] Rick Nowlin of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette gave it a three and a half stars out of four, for "a take no prisoners funk groove ... pretty much throughout", and called the album "adventurous".[17]

Charts

edit| Chart (2008) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Billboard Internet Albums | 20[19] |

| Billboard 200 | 122 |

Legacy

editDuring the production of the album, synthesizer maker Ensoniq created a Chicago-branded edition of its Signature Series of CD-ROM for use by professional audio engineers and musicians. The company recorded isolated elements of the essential sound of the band as it was to appear on Stone of Sisyphus. Intended for synthesizer users to create original music inspired by the sound of Chicago, the disc contains "various licks and articulations" which are represented to "sound exactly as it appears on record, using a combination of close and ambient microphones" from the horn section, Hammond B-3 keyboard, drum set, bass guitar, electric guitar, and vocals. The resulting disc contains a bonus audio track by Jason Scheff, titled "Evangeline".[20] Producer Peter Wolf recalls of the mutually beneficial arrangement, "We used a lot of Ensoniq gear on that record. They were the happening keyboard manufacturer, no doubt about it."[3]: 298

Myth of Sisyphus

editIn ancient Greek mythology, King Sisyphus was sentenced to roll an enchanted boulder up a hill, only to stand just before the peak and watch it roll itself back down, and to repeat this action forever. This consigned Sisyphus to an eternity of useless efforts and unending frustration, and thus it came to pass that pointless or interminable activities are sometimes described as Sisyphean.

It is suggested that Sisyphus symbolizes the vain struggle of man in the pursuit of knowledge.[21] The Myth of Sisyphus saw Sisyphus as personifying the absurdity of human life, but concludes "one must imagine Sisyphus happy" as "The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man's heart." Another philosophical interpretation involves the politician's quest for power, in itself an "empty thing".[22]

In psychological experiments that test how workers respond when the meaning of their task is diminished, the test condition is referred to as the Sisyphusian condition. The two main conclusions of the experiment are that people work harder when they can imagine meaning in their work, and that people underestimate the relationship between meaning and motivation.[23]

Track listing

editThis is the track list, as published in the final 2008 release, Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus. "Get on This" is inexplicably missing.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Stone of Sisyphus" | Dawayne Bailey, Lee Loughnane | Robert Lamm with Dawayne Bailey | 4:11 |

| 2. | "Bigger Than Elvis" | Jason Scheff, Peter Wolf, Ina Wolf | Jason Scheff | 4:31 |

| 3. | "All the Years" | Robert Lamm, Bruce Gaitsch | Lamm | 4:16 |

| 4. | "Mah-Jong" | Scheff, Brock Walsh, Aaron Zigman | Champlin | 4:42 |

| 5. | "Sleeping in the Middle of the Bed" | Lamm, John McCurry | Lamm with Champlin | 4:45 |

| 6. | "Let's Take a Lifetime" | Scheff, Walsh, Zigman | Scheff | 4:56 |

| 7. | "The Pull" | Lamm, Scheff, P. Wolf | Scheff with Lamm | 4:17 |

| 8. | "Here with Me (A Candle for the Dark)" | James Pankow, Lamm, Greg O'Connor | Lamm with Scheff and Champlin | 4:11 |

| 9. | "Plaid" | Bill Champlin, Lamm, Greg Mathieson | Champlin | 4:59 |

| 10. | "Cry for the Lost" | Champlin, Dennis Matkosky | Champlin | 5:18 |

| 11. | "The Show Must Go On" | Champlin, Gaitsch | Champlin | 5:25 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12. | "Love Is Forever" (Demo) | Pankow, Lamm | 4:14 |

| 13. | "Mah-Jong" (Demo) | Scheff, Walsh, Zigman | 4:59 |

| 14. | "Let's Take a Lifetime" (Demo) | Scheff, Walsh, Zigman | 4:15 |

| 15. | "Stone of Sisyphus" (No Rhythm Loop) | Bailey, Loughnane | 4:35 |

Personnel

editChicago

edit- Robert Lamm – keyboards, lead and backing vocals

- Lee Loughnane – trumpet, flugelhorn, backing vocals

- James Pankow – trombone, backing vocals, horn arrangements, horn co-arrangement on "Stone of Sisyphus"

- Walter Parazaider – woodwinds, backing vocals

- Bill Champlin – keyboards, rhythm guitars, lead and backing vocals

- Jason Scheff – bass guitar, lead and backing vocals

- Dawayne Bailey – rhythm guitars, lead guitar ("Bigger Than Elvis", "Stone of Sisyphus", "Love is Forever"), lead and backing vocals, horn co-arrangement on "Stone of Sisyphus"

- Tris Imboden – drums, percussion, harmonica

Additional musicians

edit- Peter Wolf – arrangements, keyboards, keyboard bass

- Bruce Gaitsch – guitars

- Sheldon Reynolds – guitars

- Jerry Scheff – bass guitar on "Bigger Than Elvis"

- The Jordanaires – backing vocals on "Bigger Than Elvis"

- Joseph Williams – backing vocals on "Let's Take a Lifetime"

Production

edit- Produced by Peter Wolf

- Engineered by Peter Wolf and Paul Ericksen

- Mixed by Tom Lord-Alge at Encore Studios, Burbank, California, in 1993 and 1994.

- Recorded at Embassy Studios in Simi Valley, California, in 1993.

- The Jordanaires recorded in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1993.

- Remastered by David Donnelly

- Audio Supervisor – Jeff Magid

- A&R Supervision – Cheryl Pawelski

- Project Assistance – Zach Cowie, Sheryl Farber, Joe Halbardier, Rob Ondarza and Steve Woolard.

- Art Direction and Design – Meat & Potatoes, Inc.

- Art Supervision – Josh Petker

- Liner Notes – Bill DeYoung

- Management – Peter Schivarelli

References

edit- ^ a b c Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus, at Allmusic at AllMusic. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Leger, Arnaud (August 5, 2008). Interview with Jason Scheff shot on july 29th 2008 in Paris (A/V stream). Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s LeRoy, Dan (2007). "Chapter 3: Chicago: Like a Rolling Stone". The Greatest Music Never Sold: Secrets of Legendary Lost Albums by David Bowie, Seal, Beastie Boys, Beck, Chicago, Mick Jagger & More! (Book). New York: Backbeat Books. ISBN 9780879309053. OCLC 145378229. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

The Greatest Music Never Sold.

- ^ Wood, Tim. "Chicago's Lost Album - The Stone of Sisyphus". Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ Sunrise on the Sufferbus, overview at Allmusic at AllMusic. Retrieved July 22, 2013.

- ^ a b Bailey, Dawayne. "Dawayne Bailey's memo on Stone of Sisyphus". Archived from the original on April 6, 2003. Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ a b Bailey, Dawayne. "Dawayne Bailey's official SoS page". Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ Imboden, Tris (December 1995). "Chicago's Tris Imboden". Modern Drummer (Interview). Interviewed by Robyn Flans. Clifton, New Jersey: Modern Drummer Publications. ISSN 0194-4533. OCLC 4660723. Retrieved June 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Payne, Ed (June 17, 2008). "Chicago releases 'lost' album 15 years after recording it". CNN. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Leger, Arnaud (August 5, 2008). Interview with Bill Champlin shot on July 29th 2008 in Paris (A/V stream). Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus, credits at Allmusic at AllMusic. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ Night & Day: Big Band, overview at Allmusic at AllMusic. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ a b c Iwaski, Scott (July 4, 2008). "'Stone of Sisyphus' worth the wait". Deseret News. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Pankow, Jimmy; Lamm, Robert (March 4, 1999). "Interview with Robert Lamm and Jimmy Pankow, Chicago". Goldmine Magazine (Interview). Interviewed by Debbie Kruger (published 1999).

- ^ Chicago (1993). Chicago: In Concert at Greek Theatre (VHS). Burbank, CA: Warner Reprise Video. OCLC 30707603.

- ^ "CHICAGO PUSHES SISYPHUS OVER THE TOP" (Press release). Los Angeles, California: Rhino Records. May 1, 2008. Archived from the original on January 23, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Nowlin, Rick (August 29, 2008). "For The Record". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 59 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Collette, Doug (September 3, 2008). "Chicago: Stone of Sisyphus". Glide Magazine. Glide Publishing LLC. Retrieved July 21, 2013.

- ^ "Chicago XXXII: Stone of Sisyphus". billboard.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019.

- ^ Bailey, Dawayne. "Dawayne Bailey: Ensoniq's Signature Series". Retrieved July 19, 2013.

- ^ Revue archéologique. 1904.

- ^ Esolen, Anthony M. (1995) [1st century BC]. "De Rerum Natura III". On the Nature of Things: De rerum natura (didactic poem). transl. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Univ. Pr. ISBN 0-8018-5055-X.

- ^ Ariely, Dan (2010). The Upside of Irrationality. ISBN 978-0-06-199503-3.