The Revenger's Tragedy is an English-language Jacobean revenge tragedy which was performed in 1606, and published in 1607 by George Eld. It was long attributed to Cyril Tourneur, but "The consensus candidate for authorship of The Revenger’s Tragedy at present is Thomas Middleton, although this is a knotty issue that is far from settled."[1]

A vivid and often violent portrayal of lust and ambition in an Italian court, the play typifies the satiric tone and cynicism common in many Jacobean tragedies. The play fell out of favour before the restoration of the theaters in 1660; however, it experienced a revival in the 20th century among directors and playgoers who appreciated its affinity with the temper of modern times.[2]

Characters

edit- Vindice, the revenger, frequently disguised as Piato (both the 1607 and 1608 printings render his name variously as Vendici, Vindic, and Vindice, with the latter spelling most frequent; in later literature Vendice[3]).

- Hippolito, Vindice's brother, sometimes called Carlo

- Castiza, their sister

- Gratiana, a widow, and mother of Vindice, Hippolito, and Castiza

- The Duke

- The Duchess, the duke's second wife

- Lussurioso, the duke's son from an earlier marriage, and his heir

- Spurio, the duke's second son, a bastard

- Ambitioso, the duchess's eldest son

- Supervacuo, the duchess's middle son

- Junior Brother, the duchess's third son

- Antonio, a discontented lord at the Duke's court

- Antonio's wife, raped by Junior Brother

- Piero, a discontented lord at the Duke's court

- Nobles, allies of Lussurioso

- Lords, followers of Antonio

- The Duke's gentlemen

- Two Judges

- Spurio's two Servants

- Four Officers

- A Prison-Keeper

- Dondolo, Castiza's servant

- Nencio and Sordido, Lussurioso's servants

- Ambitioso's henchman

Synopsis

editThe play is set in an unnamed Italian court.

Act I

editVindice broods over his fiancée's recent death and his desire for revenge on the lustful Duke for poisoning his beloved nine years before. Vindice's brother Hippolito brings news: Lussurioso, the Duke's heir by his first marriage, has asked him if he can find a procurer to obtain a young virgin he lusts after. The brothers decide that Vindice will undertake this role in disguise, to give an opportunity for their revenge. Meanwhile, Lord Antonio's wife has been raped by the new Duchess's youngest son Junior. He brazenly admits his guilt, even joking about it, but to widespread surprise the Duke suspends the proceedings and defers the court's judgement. The Duchess's other sons, Ambitioso and Supervacuo, whisper a promise to have him freed; the Duchess vows to be unfaithful to the Duke. Spurio, the Duke's bastard son, agrees to be her lover but when alone, declares he hates her and her sons as intensely as he hates the Duke and Lussurioso. Vindice, disguised as "Piato," is accepted by Lussurioso, who tells him that the virgin he desires is Hippolito's sister, Castiza; and he predicts her mother will accept a bribe and be a 'bawd to her own daughter'. Vindice, alone, vows to kill Lussurioso, but decides meanwhile to stay in disguise and put his mother and sister to the test by tempting them. Antonio's wife commits suicide; Antonio displays her dead body to fellow mourners and Hippolito swears all those present to revenge her death.

Act II

editVindice, disguised as "Piato," tests the virtue of his sister and mother. Castiza proves resolute but his mother yields to an offer of gold. Vindice gives Lussurioso the false news that Castiza's resistance to his advance is crumbling. Lussurioso resolves he must sleep with her that same night. Hippolito and Vindice, by chance, overhear a servant tell Spurio that Lussurioso intends to sleep with Castiza "within this hour." Spurio rushes away to kill Lussurioso in flagrante delicto. A moment later Lussurioso himself enters, on his way to Castiza, but Vindice deceptively warns him that Spurio is bedding the Duchess. Angered, Lussurioso rushes off to find Spurio and bursts into the ducal bedchamber, only to find his father lawfully in bed with the Duchess. Lussurioso is arrested for attempting treason; in the excitement, Hippolito and Vindice discreetly withdraw. The Duke, seeing through Ambitioso and Supervacuo's pretended reluctance to see Lussurioso executed, dispatches them with a warrant for the execution of his son "ere many days," but once they have gone he gives a countermanding order for his son's release.

Act III

editAmbitioso and Supervacuo set off directly to the prison to order the instant execution of Lussurioso. Before they arrive however (and unknown to them) the Duke's countermanding order is obeyed and Lussurioso is freed. Ambitioso and Supervacuo arrive at the prison and present the Duke's first warrant to execute, in their words, "our brother the duke's son." The guards misinterpret these words, taking instead the youngest son out to instant execution. Meanwhile, Vindice is hired again as a pander – this time by the Duke himself. His plan is to procure the Duke an unusual lady – a richly clothed effigy, her head, the skull of Vindice's beloved, is covered with poison. The meeting is in a dark and secret place near where the Duchess has arranged a meeting with Spurio. The Duke is poisoned by kissing the supposed lady and is subsequently stabbed by Vindice after being forced to watch the Duchess betray him with Spurio. Ambitioso and Supervacuo, still confident that Lussurioso has been executed, both look forward to succeeding the throne in his place. A freshly severed head is brought in from prison. Assuming it is Lussurioso's, they are gloating over it when Lussurioso himself arrives, alive. They realize to their dismay that the head is the youngest son's.

Act IV

editLussurioso tells Hippolito he wants to get rid of "Piato," and asks if Vindice (of whom he knows only by report) would replace him. Hippolito assents, realizing that Lussurioso would not recognize Vindice without a disguise. Vindice gets his new mission – to kill "Piato". Hippolito and Vindice take the corpse of the Duke and dress it in "Piato's" clothes, so when the corpse is found it will be assumed that "Piato" murdered the Duke then switched clothes with him to escape. Vindice and Hippolito confront Gratiana for her earlier willingness to prostitute Castiza bringing her to repentance.

Act V

editThe scheme with the Duke's corpse is successful and the Duke's death becomes public knowledge. Vindice and Hippolito lead a group of conspirators which, shortly after the installation of Lussurioso as Duke, kills the new Duke and his supporters. A second group of murderers including Supervacuo, Ambitioso, and Spurio then arrives; they discover their intended victims already dead, and then turn on and kill each other. The dying Lussurioso is unable to expose Vindice's treacheries to Lord Antonio. Exhilarated by his success and revenge, Vindice confides in Antonio that he and his brother murdered the old Duke. Antonio, appalled, condemns them to execution. Vindice, in a final speech, accepts his death.

Context

editThe Revenger's Tragedy belongs to the second generation of English revenge plays. It keeps the basic Senecan design brought to English drama by Thomas Kyd: a young man is driven to avenge an elder's death (in this case it's a lover, Gloriana, instead), which was caused by the villainy of a powerful older man; the avenger schemes to effect his revenge, often by morally questionable means; he finally succeeds in a bloodbath that costs him his own life as well. However, the author's tone and treatment are markedly different from the standard Elizabethan treatment in ways that can be traced to both literary and historical causes. Already by 1606, the enthusiasm that accompanied James I's assumption of the English throne had begun to give way to the beginnings of dissatisfaction with the perception of corruption in his court. The new prominence of tragedies that involved courtly intrigues seems to have been partly influenced by this dissatisfaction.

This trend towards court-based tragedy was contemporary with a change in dramatic tastes toward the satiric and cynical, beginning before the death of Elizabeth I but becoming ascendant in the few years following. The episcopal ban on verse satire in 1599 appears to have impelled some poets to a career in dramaturgy;[4] writers such as John Marston and Thomas Middleton brought to the theatres a lively sense of human frailty and hypocrisy. They found fertile ground in the newly revived children's companies, the Blackfriars Children and Paul's Children;[5] these indoor venues attracted a more sophisticated crowd than that which frequented the theatres in the suburbs.

While The Revenger's Tragedy was apparently performed by an adult company at the Globe Theatre, its bizarre violence and vicious satire mark it as influenced by the dramaturgy of the private playhouses.

Analysis and criticism

editGenre

editIgnored for many years, and viewed by some critics as the product of a cynical, embittered mind,[6] The Revenger's Tragedy was rediscovered and often performed as a black comedy during the 20th century. The approach of these revivals mirrors shifting views of the play on the part of literary critics. One of the most influential 20th-century readings of the play is by the critic Jonathan Dollimore, which claims that the play is essentially a form of radical parody that challenges orthodox Jacobean beliefs about Providence and patriarchy.[7] Dollimore asserts the play is best understood as "subversive black camp" insofar as it "celebrates the artificial and the delinquent; it delights in a play full of innuendo, perversity and subversion ... through parody it declares itself radically skeptical of ideological policing though not independent of the social reality which such skepticism simultaneously discloses".[8] In Dollimore's view, earlier critical approaches, which either emphasise the play's absolute decadence or find an ultimate affirmation of traditional morality in the play, are insufficient because they fail to take into account this vital strain of social and ideological critique running throughout the tragedy.

Themes and motifs

editGender

editThe Duchess, Castiza, and Gratiana are the only female characters in the play. Gratiana ("grace"), Vindice's mother, exemplifies female frailty. This is such a stereotyped role that it discourages looking at her circumstance in the play, but because she is a widow it could be assumed to include financial insecurity, which could help explain her susceptibility to bribery. Her daughter also has an exemplary name, Castiza ("chastity"), as if to fall in line with the conventions of the Morality drama, rather than the more individualized characterization seen in their counterparts in Hamlet, Gertrude and Ophelia. Due to the ironic and witty matter in which The Revenger's Tragedy handles received conventions, however, it is an open question as to how far the presentation of gender in the play is meant to be accepted as conventional, or instead as parody. The play is in accordance with the medieval tradition of Christian Complaint, and Elizabethan satire, in presenting sexuality mainly as symptomatic of general corruption. Even though Gratiana is the mother of a decent, strong-minded daughter, she finds herself acting as a bawd. This personality-split is then repeated, in an episode exactly reversing the pattern, by her ironic, intelligent daughter.[9]

Michael Neill notes that the name "Spurio" derives from the Latin term "spurius" which does not mean just any illegitimate offspring, but "one born from a noble but spouseless mother to an unknown or plebeian father." These children, who could not take the paternal name, were called "spurius" because they sprang in effect from the mother alone—the word itself deriving from "spurium," an ancient term for the female genitalia. As Thomas Laqueur puts it, "while the legitimate child is from the froth of the father, the illegitimate child is from the seed of the mother's genitals, as if the father did not exist." The idea of Spurio and his character provides the function of "bastardy in the misogynist gender politics of the play."[10]

Necrophilia

editWhile the play does not quite imply sexual intercourse with a corpse, some critics have found a strong connection to desire that can be found in the instances where the skull is used. According to Karin S. Coddon, there is a sense of macabre eroticism that pervades the work. She notes that "Gloriana's skull is a prop endowed with remarkable spectacular and material efficacy."[11] Vindice has kept the skull long after his beloved's death and has used it to attract the duke to his death, a kiss of death was bestowed. Considering the description of the skull it should be impossible to discern its gender yet throughout in each section it is mentioned with the gender of a woman attributed to a woman. Vindice's use of the skull to kill the duke borders on a form of prostitution which also implies the sexual nature surrounding the partial corpse. Vindice, in act 3, scene 5 enters "with the skull of his love dressed up in tires"; in Coddon's view, the skull's gendering is clearly a contrivance.[11]

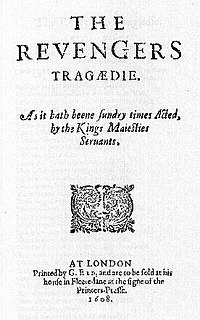

Authorship

editThe play was published anonymously in 1607; the title page of this edition announced that it had been performed "sundry times" by the King's Men (Loughrey and Taylor, xxv). A second edition, also anonymous (actually consisting of the first edition with a revised title-page), was published later in 1607. The play was first attributed to Cyril Tourneur by Edward Archer in 1656; the attribution was seconded by Francis Kirkman in lists of 1661 and 1671.[12] Tourneur was accepted as the author despite Archer's unreliability and the length of time between composition and attribution (Greg, 316). Edmund Kerchever Chambers cast doubt on the attribution in 1923 (Chambers, 4.42), and over the course of the twentieth century a considerable number of scholars argued for attributing the play to Thomas Middleton.[12] There are indications that this play was submitted by Middleton to Robert Keysar of The Queen's Revels company under the name of The Viper and Her Brood.[13] The critics who supported the Tourneur attribution argued that the tragedy is unlike Middleton's other early dramatic work, and that internal evidence, including some idiosyncrasies of spelling, points to Tourneur.[12] More recent scholarly studies arguing for attribution to Middleton point to thematic and stylistic similarities to Middleton's other work, to the differences between The Revenger's Tragedy and Tourneur's other known play, The Atheist's Tragedy, and to contextual evidence suggesting Middleton's authorship (Loughrey and Taylor, xxvii). In Shakespeare's Borrowed Feathers, Darren Freebury-Jones provides overwhelming computational evidence in favour of Middleton rather than Tourneur's authorship, showing that the play's language closely approximates Middleton's style but is far removed from Tourneur's.[14]

The play is attributed to Middleton in Jackson's facsimile edition of the 1607 quarto (1983), in Bryan Loughrey and Neil Taylor's edition of Five Middleton Plays (Penguin, 1988), and in Thomas Middleton: The Collected Works (Oxford, 2007). Two important editions of the 1960s that attributed the play to Tourneur switched in the 1990s to stating no author (Gibbons, 1967 and 1991) or to crediting "Tourneur/Middleton" (Foakes, 1966 and 1996), both now summarising old arguments for Tourneur's authorship without endorsing them.

Influences

editThe Revenger's Tragedy is influenced by Seneca and Medieval theatre. It is written in 5 acts[15] and opens with a monologue that looks back at previous events and anticipates future events. This monologue is spoken by Vindice, who says he will take revenge and explains the corruption in court. It uses onomastic rhetoric in Act 3, scene 5 where characters play upon their own names, a trait considered to be Senecan.[16] The verbal violence is seen as Senecan, with Vindice in Act 2, scene 1, calling out against heaven, "Why does not heaven turn black or with a frown/Undo the world?"

The play also adapts Senecan attributes with the character Vindice. At the end of the play he is a satisfied revenger, which is typically Senecan. However, he is punished for his revenge, unlike the characters in Seneca's Medea and Thyestes.[17] In another adaptation of Seneca, there is a strong element of meta-theatricality as the play makes references to itself as a tragedy. For example, in Act 4, scene 2, "Vindice: Is there no thunder left, or is't kept up /In stock for heavier vengeance [Thunder] There it goes!"

Along with influences from Seneca, this play is said to be very relevant to, or even about, Shakespeare's Hamlet. The differences between the two, however, stem from the topic of "moral disorientation" found in The Revenger's Tragedy which is unlike anything found in a Shakespeare play. This idea is discussed in a scholarly article written by Scott McMillin, who addresses Howard Felperin's views of the two plays. McMillin goes on to disagree with the idea of a "moral disorientation", and finds The Revenger's Tragedy to be perfectly clear morally. McMillin asserts The Revenger's Tragedy is truly about theater, and self-abandonment within theatrics and the play itself. It is also noted that the most common adverb in The Revenger's Tragedy is the word "now" which emphasizes the compression of time and obliteration of the past. In Hamlet time is discussed in wider ranges, which is especially apparent when Hamlet himself thinks of death. This is also very different from Vindice's dialogue, as well as dialogue altogether in The Revenger's Tragedy.[18]

The medieval qualities in the play are described by Lawrence J. Ross as, "the contrasts of eternity and time, the fusion of satirically realistic detail with moral abstraction, the emphatic condemnation of luxury, avarice and superfluity, and the lashing of judges, lawyers, usurers and women."[19] To personify Revenge is seen as a Medieval characteristic.[20] Although The Revenger's Tragedy does not personify this trait with a character, it is mentioned in the opening monologue with a capital, thereby giving it more weight than a regular noun.

Performance history

editThe play was entered in the Stationer's Register on 7 October 1607 and was performed by the King's Men. The main house that the play was performed in was the Globe Theatre, but it was also performed at court, on tour, or in the Blackfriars Theatre.[21]

A Dutch adaptation, Wraeck-gierigers treur-spel, translated by Theodore Rodenburgh, was performed and published in 1618.[22]

It was produced at the Pitlochry Festival Theatre in 1965. The following year, Trevor Nunn produced the play for the Royal Shakespeare Company; Ian Richardson played Vindice. Executed on a tight budget (designer Christopher Morley had to use the sets from the previous year's Hamlet), Nunn's production earned largely favourable reviews.[23]

In 1987, Di Trevis revived the play for the RSC at the Swan Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon; Antony Sher played Vindice. It was also staged by the New York Protean Theatre in 1996. A Brussels theatre company called Atelier Sainte-Anne, led by Philippe Van Kessel, also staged the play in 1989. In this production, the actors wore punk costumes and the play took place in a disquieting underground location which resembled both a disused parking lot and a ruined Renaissance building.

In 1976, Jacques Rivette made a loose French film adaptation Noroît, which changed the major characters into women, and included several poetic passages in English; it starred Geraldine Chaplin, Kika Markham, and Bernadette Lafont.

In 2002, a film adaptation entitled Revengers Tragedy was directed by Alex Cox with a heavily adapted screenplay by Frank Cottrell Boyce. The film is set in a post-apocalyptic Liverpool (in the then future 2011) and stars Christopher Eccleston as Vindice, Eddie Izzard as Lussurioso, Diana Quick as The Duchess and Derek Jacobi as The Duke. It was produced by Bard Entertainment Ltd.

In 2005 the play was produced at London's Southwark Playhouse with Kris Marshall as Vindice and was directed by Gavin McAlinden.

In 2008, two major companies staged revivals of the play: Jonathan Moore directed a new production at the Royal Exchange, Manchester from May to June 2008, starring Stephen Tompkinson as Vindice, while a National Theatre production at the Olivier Theatre was directed by Melly Still, starring Rory Kinnear as Vindice, with music by Adrian Sutton and featuring a soundtrack performed by a live orchestra and DJs Differentgear.

In 2018, a stage adaptation was directed by Cheek by Jowl's Declan Donnellan at the Piccolo Teatro. The production toured in Italy in early 2019 and in Europe in early 2020.[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Walsh, Brian. The Revenger’s Tragedy: A Critical Reader. Bloomsbury, 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Wells, p. 106

- ^ Stewart, Mary (1916–2014). "Chapter I". Nine Coaches Waiting. HarperCollins Publishers, First HarperTorch paperback printing, December 2001. p. 7. ISBN 0380820765.

- ^ Campbell, 3

- ^ Harbage, passim

- ^ Ribner, Irving (1962) Jacobean Tragedy: the quest for moral order. London: Methuen; New York, Barnes & Noble; p. 75 (Refers to several other authors.)

- ^ Dollimore, Jonathan (1984) Radical Tragedy: Religion, Ideology and Power in the Drama of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; pp. 139–50.

- ^ Dollimore, p. 149.

- ^ Gibbons, B. (2008). The Revenger's Tragedy (3rd ed., pp. Xxiii-xxiv). London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama.

- ^ Neill, Michael (1996). "Bastardy, counterfeiting, and misogyny in 'The Revenger's Tragedy.'". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 36 (2): 397–416. doi:10.2307/450955. JSTOR 450955.

- ^ a b Coddon, Karin S. (1994). ""For Show or Useless Property": Necrophilia and the Revenger's Tragedy". ELH. 61. Johns Hopkins University Press: 71–88. doi:10.1353/elh.1994.0001. ISSN 1080-6547. S2CID 170881312.

- ^ a b c Gibbons, ix

- ^ Neill, Michael (1996). "Bastardy, Counterfeiting, and Misogyny in The Revenger's Tragedy". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 36 (2). Rice University: 397–398. doi:10.2307/450955. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 450955.

- ^ Freebury-Jones, Darren (2024). Shakespeare's Borrowed Feathers: How Early Modern Playwrights Shaped the World's Greatest Writer. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-1-5261-7732-2.

- ^ Baker, Howard. "Ghosts and Guides: Kyd's 'Spanish Tragedy' and the Medieval Tragedy". Modern Philology 33.1 (1935): p. 27

- ^ Boyles, A. J. Tragic Seneca. London: Routledge, 1997, p. 162

- ^ Ayres, Phillip J. "Marston's Antonio's Revenge: The Morality of the Revenging Hero". Studies in English Literature: 1500–1900 12.2, p. 374

- ^ McMillin, Scott (1984). "Acting and Violence: The Revenger's Tragedy and Its Departures from Hamlet". SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900. 24 (2): 275–291. doi:10.2307/450528. JSTOR 450528.

- ^ Tourneur, Cyril. The Revenger's Tragedy. Lawrence J. Ross, ed. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966, p. xxii

- ^ Baker, p. 29

- ^ Gibbons, B. (2008). The Revenger's Tragedy (3rd ed., pp. Xxvii-xxviii). London: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama.

- ^ Smith, Nigel (24 May 2018). "Polyglot Poetics: Transnational Early Modern Literature, part II". The Collation. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 9 November 2019.

- ^ "Revenger's". alanhoward.org.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ "The Revenger's Tragedy (La tragedia del vendicatore)". Barbican Centre. 4 March 2020.

Further reading

edit- Campbell, O. J. Comicall Satyre and Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida. San Marino, CA: Huntington Library Publications, 1938

- Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Theatre. Four Volumes. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923.

- Foakes, R. A. Shakespeare; the Dark Comedies to the Last Plays. London: Routledge, 1971

- Foakes, R. A., ed. The Revenger's Tragedy. (The Revels Plays.) London: Methuen, 1966. Revised as Revels Student edition, Manchester University Press, 1996

- Gibbons, Brian, ed. The Revenger's Tragedy; New Mermaids edition. New York: Norton, 1967; Second edition, 1991

- Greg, W. W. "Authorship Attribution in the Early Play-lists, 1656–1671." Edinburgh Bibliographical Society Transactions 2 (1938–1945)

- Griffiths, T, ed. The Revenger's Tragedy. London: Nick Hern Books, 1996

- Harbage, Alfred Shakespeare and the Rival Traditions. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 1952

- Loughrey, Bryan and Taylor, Neil. Five Plays of Thomas Middleton. New York: Penguin, 1988

- Wells, Stanley "The Revenger's Tragedy Revived." The Elizabethan Theatre 6 (1975)