The Years is a 1937 novel by Virginia Woolf, the last she published in her lifetime. It traces the history of the Pargiter family from the 1880s to the "present day" of the mid-1930s.

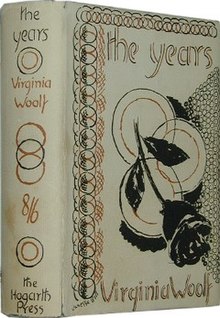

First edition cover | |

| Author | Virginia Woolf |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Vanessa Bell |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Hogarth Press |

Publication date | 1937 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 444 pp |

| OCLC | 7778524 |

Although spanning fifty years, the novel is not epic in scope, focusing instead on the small private details of the characters' lives. Except for the first, each section takes place on a single day of its titular year, and each year is defined by a particular moment in the cycle of seasons. At the beginning of each section, and sometimes as a transition within sections, Woolf describes the changing weather all over Britain, taking in both London and countryside as if in a bird's-eye view before focusing in on her characters. Although these descriptions move across the whole of England in single paragraphs, Woolf only rarely and briefly broadens her view to the world outside Britain.

Development

editThe novel had its inception in a lecture Woolf gave to the London/National Society for Women's Service on 21 January 1931, an edited version of which would later be published as "Professions for Women".[1] Having recently published A Room of One's Own, Woolf thought of making this lecture the basis of a new book-length essay on women, this time taking a broader view of their economic and social life, rather than focusing on women as artists, as the first book had. As she was working on correcting the proofs of The Waves and beginning the essays for The Common Reader, Second Series, the idea for this essay took shape in a diary entry for 16 February 1932: "And I'm quivering & itching to write my--whats it to be called?--'Men are like that?'--no thats too patently feminist: the sequel then, for which I have collected enough poweder to blow up St Pauls. It is to have 4 pictures" (capitalization and punctuation as in manuscript).[2] The reference to "4 pictures" in this diary entry shows the early connection between The Years and Three Guineas, which would, indeed, include photographs.[3] On 11 October 1932, she titled the manuscript "THE PARGITERS: An Essay based upon a paper read to the London/National Society for Women's Service" (capitalization as in manuscript).[4][5] During this time, the idea of mixing the essay with fiction occurred to her, and in a diary entry of 2 November 1932, she conceived the idea of a "novel-essay" in which each essay would be followed by a novelistic passage presented as extracts from an imaginary longer novel, which would exemplify the ideas explored in the essay.[6] Woolf began to collect materials about women's education and lives since the later decades of the 19th century, which she copied into her reading notebooks or pasted into scrapbooks, hoping to incorporate them into the essay portions of The Pargiters (they would ultimately be used for Three Guineas).[7]

Between October and December 1932 Woolf wrote six essays and their accompanying fictional "extracts" for The Pargiters. By February 1933, however, she jettisoned the theoretical framework of her "novel-essay" and began to rework the book solely as a fictional narrative, although Anna Snaith argued in her introduction to the Cambridge edition of the novel that "Her decision to cut the essays was not a rejection of the project's basis in non-fiction, but affirmation of its centrality to the project, and to her writing in general."[8] Some of the conceptual material presented in The Pargiters eventually made its way into her non-fiction essay-letter, Three Guineas (1938). In 1977 a transcription of the original draft of six essays and extracts, together with the lecture that first inspired them, was edited by Mitchell Leaska and published under the title The Pargiters.

Woolf's manuscripts of The Years, including the draft from which The Pargiters was prepared, are in the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature in the New York Public Library.

Plot summary

edit1880

edit"It was an uncertain Spring."

Colonel Abel Pargiter visits his mistress Mira in a dingy suburb, then returns home to his children and his invalid wife Rose. His eldest daughter Eleanor is a do-gooder in her early twenties, and Milly and Delia are in their teens. Morris, the eldest brother, is already a practising barrister. Delia feels trapped by her mother's illness and looks forward to her death. Ten-year-old Rose quarrels with twelve-year-old Martin and sneaks off by herself to a nearby toyshop. On the way back she is frightened by a man exposing himself. As the family prepares for bed, Mrs Pargiter seems at last to have died, but she recovers.

At Oxford it is a rainy night and undergraduate Edward, the last Pargiter sibling, reads Antigone and thinks of his cousin Kitty Malone, with whom he is in love. He is distracted by two friends, the athletic Gibbs and the bookish Ashley.

Daughter of a Head of House at Oxford, cousin Kitty endures her mother's academic dinner-parties, studies half-heartedly with an impoverished female scholar named Lucy Craddock, and considers various marriage prospects, dismissing Edward. She is sitting with her mother when the news is brought that Mrs Pargiter is dead.

At Mrs Pargiter's funeral Delia distracts herself with romantic fantasies of Charles Stewart Parnell and struggles to feel any real emotional response to her mother's death.

1891

edit"An Autumn wind blew over England."

Kitty has married the wealthy Lord Lasswade, as her mother predicted, and Milly has married Edward's friend Gibbs. They are at a hunting party at the Lasswade estate. Back in London, Eleanor, now in her thirties, runs her father's household and does charity work to provide improved housing for the poor. Travelling to London on a horse-drawn omnibus she visits her charity cases, reads a letter from Martin (twenty-three and having adventures in India), and visits court to watch Morris argue a case. Morris is married to Celia. Back in the street, Eleanor reads the news of Parnell's death and tries to visit Delia, living alone and still an avid supporter of the Irish politician, but Delia is not at home.

Colonel Pargiter visits the family of his younger brother, Sir Digby Pargiter. Digby is married to the flamboyant Eugénie and has two little daughters, Maggie and Sara (called Sally).

1907

edit"It was midsummer; and the nights were hot."

Digby and Eugénie bring Maggie home from a dance where she spoke with Martin, who has returned from Africa. At home, Sara lies in bed reading Edward's translation of Antigone and listening to another dance down the street. Sara and Maggie are now in their mid-twenties. Maggie arrives home, and the girls tease their mother about her romantic past.

1908

edit"It was March and the wind was blowing."

Martin, now forty, visits the house of Digby and Eugénie, which has already been sold after their sudden deaths. He goes to see Eleanor, now in her fifties. Rose, pushing forty and an unmarried eccentric, also drops in.

1910

edit"...an English spring day, bright enough, but a purple cloud behind the hill might mean rain."

Rose, forty, visits her cousins Maggie and Sara (or Sally), who are living together in a cheap apartment. Rose takes Sara to one of Eleanor's philanthropic meetings. Martin also comes, and so does their glamorous cousin Kitty Lasswade, now nearing fifty. After the meeting Kitty visits the opera. That evening at dinner Maggie and Sara hear the cry go up that King Edward VII is dead.

1911

edit"The sun was rising. Very slowly it came up over the horizon shaking out light."

The chapter begins with a brief glimpse of the south of France, where Maggie has married a Frenchman named René (or Renny) and is already expecting a baby. In England Colonel Pargiter has died and the family's old house is shut up for sale. Eleanor visits her brother Morris and Celia, who have a teenaged son and daughter named North and Peggy (another son, Charles, is mentioned in a later section). Also visiting is Sir William Whatney, one of spinster Eleanor's few youthful flirtations. There is gossip that Rose has been arrested for throwing a brick (this was a time of Suffragette protests).

1913

edit"It was January. Snow was falling. Snow had fallen all day."

The Pargiters' family home is being sold and Eleanor says goodbye to the housekeeper, Crosby, who must now take a room in a boarding house after forty years in the Pargiters' basement. From her new lodgings Crosby takes the train across London to collect the laundry of Martin, now forty-five and still a bachelor.

1914

edit"It was a brilliant spring day; the day was radiant."

It is May 1914, two months before the outbreak of World War I, although no hint is given of this.

Wandering past St Paul's Cathedral, Martin runs into his cousin Sara (or Sally), now in her early thirties. They have lunch together at a chop shop, then walk through Hyde Park and meet Maggie with her baby. Martin mentions that his sister Rose is in prison. Martin continues, alone, to a party being given by Lady Lasswade (cousin Kitty). At the party he meets teenage Ann Hillier and Professor Tony Ashton, who attended Mrs Malone's dinner party in 1880 as an undergraduate. The party over, Kitty changes for a night train ride to her husband's country estate, then is driven by motorcar to his castle. She walks through the grounds as day breaks.

1917

edit"A very cold winter's night, so silent that the air seemed frozen"

During the war Eleanor visits Maggie and Renny, who have fled France for London. She meets their openly gay friend Nicholas, a Polish-American. Sara arrives late, angry over a quarrel with North, who is about to leave for the front lines and whose military service Sara views with contempt. There is a bombing raid, and the party takes its supper to a basement room for safety.

1918

edit"A veil of mist covered the November sky;"

The briefest of the sections, at little more than three pages in most editions of the novel, "1918" shows us Crosby, now very old and with pain in her legs. She hobbles home from work with her new employers, whom she considers "dirty foreigners", not "gentlefolk" like the Pargiters. Suddenly guns and sirens go off, but it is not the war, it is the news that the war has ended.

Present Day

edit"It was a summer evening; the sun was setting;"

Morris's son North, who is in his thirties, has returned from Africa, where he ran an isolated ranch in the years after the war. He visits Sara, in her fifties and living alone in a cheap boarding-house, and they recall the friendship they carried on for years by mail.

North's sister Peggy, a doctor in her late thirties, visits Eleanor, who is over seventy. Eleanor is an avid traveller, excited and curious about the modern age, but the bitter, misanthropic Peggy prefers romantic stories of her aunt's Victorian past. The two pass the memorial to Edith Cavell in Trafalgar Square and Peggy's brother Charles, who died in the war, is mentioned for the first and only time.

Delia, now in her sixties, married an Irishman long ago and moved away, but she is visiting London and gives a party for her family. All the surviving characters gather for the reunion.

1880 in The Pargiters

editThe draft written in 1932 and published in The Pargiters (see above) is in many respects the same as the finished "1880" section of The Years. However, Woolf made a number of significant alterations and provided a family tree with specific birth dates for the characters, many of whose ages are only implied in the finished novel. This diagram lists Colonel Pargiter as dying in 1893, while in the novel he survives till 1910, so the birth dates may not be definitive either. Editor Mitchell Leaska notes that, when figuring out the ages of the characters by sums jotted in the margins of the draft, Woolf makes a number of errors in arithmetic, a problem that also afflicts Eleanor in the novel.

- First Essay A version of the lecture that inspired the novel, the opening essay is addressed to an imaginary live audience. It describes a multi-volume novel in progress, called The Pargiters, which purports to trace the history of the family from the year 1800 to 2032. The family is described as "English life at its most normal, most typical, and most representative".

- First Chapter Begins with the heading "Chapter Fifty-Six," going along with the conceit that it is an extract from an existing longer novel. Similar to the scene that introduces the Pargiter children in the novel.

- Second Essay Discusses the reasons for the Pargiter daughters' idleness and lack of education, including the social strictures that stifle the girls' sexual impulses and cause the musically talented Delia to neglect her violin.

- Second Chapter Similar to the passages in the novel describing Rose's trip to the toy store, but dwells in more detail on the shock of the attack and Rose's fear and guilt later that night.

- Third Essay Refers to the attempted sexual assault on Rose as "one of the many kinds of love" and notes that it "raged everywhere outside the drawing room" but was never mentioned in the work of Victorian novelists. Discusses the way the assault strains Rose's relationship with her brother Martin (in this draft called "Bobby") and his greater freedom in sexual matters. Briefly introduces a suffragette character, Nora Graham.

- Third Chapter Similar to Edward's Oxford scene in the finished novel. In a deleted passage, Edward imagines Antigone and Kitty fused into a single glamorous figure and struggles with the urge to masturbate, writing a poem in Greek to calm down. Edward's friend Ashley is called "Jasper Jevons" in this version.

- Fourth Essay Describes the centuries-long tradition of all-male education at Oxford and its influence on Edward's sexual life, contrasted with the limited education available to women. Here Ashley/Jevons is called "Tony Ashton," and once in the following chapter Tony Ashton is called "Tony Ashley," suggesting that these various names originally referred to a single character in Woolf's mind. It is specified that Edward and Kitty's mothers are cousins, a relationship left unstated in the novel.

- Fourth Chapter Similar to Kitty's introductory scenes in the novel. There is more detail on her dislike for (and sympathy with) Tony Ashton's effeminacy. It's revealed that Kitty's mother comes of Yorkshire farming stock, and Kitty recalls with pleasure being kissed under a haystack by a farmer's son.

- Fifth Essay More detail on Kitty's awkward closeness with her teacher Lucy Craddock, Miss Craddock's own frustrated academic hopes, and the reaction of male academics to intellectual women. Miss Craddock has another less pretty and more studious pupil named Nelly Hughes, of the family who in the novel are called "the Robsons."

- Fifth Chapter Similar to the scene of Kitty's visit to the Robsons (here changed from "the Hughes" to "the Brooks"), who are determined that Nelly will succeed academically. Kitty enjoys sharing Yorkshire roots with the mother, and more detail is given on her attraction to the son of the family. The chapter ends with Kitty determined to leave Oxford and become a farmer's wife.

- Sixth Essay Discusses the genteel feminine ideal to which Kitty and her mother must aspire, and contrasts it with the sincere respect for women of the working-class Mr. Brook. Ends in praise of Joseph Wright, a real-life scholar whose collaboration with his wife Woolf admired.

References

edit- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1977). Leaska, Mitchell A. (ed.). The Pargiters: The Novel-Essay Portion of The Years. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. pp. xxvii–xliv. ISBN 0-15-671380-2.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1983). Bell, Anne Olivier; McNeillie, Andrew (eds.). Diary of Virginia Woolf, vol. 4 (1931-1935). New York: Harcourt Brace & Co. p. 77. ISBN 978-0156260398.

- ^ Humm, Maggie (Winter 2003). "Memory, Photography, and Modernism: The "dead bodies and ruined houses" of Virginia Woolf's Three Guineas" (PDF). Signs. 28 (2): 645–663. doi:10.1086/342583. JSTOR 10.1086/342583.

- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1977). Leaska, Mitchell A. (ed.). The Pargiters: The Novel-Essay Portion of The Years. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. pp. xvi, 4. ISBN 0-15-671380-2.

- ^ Snaith 2012, p.l

- ^ Woolf, Virginia (1983). Bell, Anne Olivier; McNeillie, Andrew (eds.). Diary of Virginia Woolf, vol. 4 (1931-1935). New York: Harcourt Brace & Co. p. 129. ISBN 978-0156260398.

- ^ Snaith 2012, p.li

- ^ Snaith 2012, p.lxiii

Further reading

edit- Radin, Grace (1982). Virginia Woolf's the Years: The Evolution of a Novel, University of Tennessee Press.

- Snaith, Anna (2012). "Introduction", The Years, Cambridge University Press: The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Virginia Woolf.