Dietrich von Bern is the name of a character in Germanic heroic legend who originated as a legendary version of the Ostrogothic king Theodoric the Great. The name "Dietrich", meaning "Ruler of the People", is a form of the Germanic name "Theodoric". In the legends, Dietrich is a king ruling from Verona (Bern) who was forced into exile with the Huns under Etzel by his evil uncle Ermenrich. The differences between the known life of Theodoric and the picture of Dietrich in the surviving legends are usually attributed to a long-standing oral tradition that continued into the sixteenth century. Most notably, Theodoric was an invader rather than the rightful king of Italy and was born shortly after the death of Attila and a hundred years after the death of the historical Gothic king Ermanaric. Differences between Dietrich and Theodoric were already noted in the Early Middle Ages and led to a long-standing criticism of the oral tradition as false.

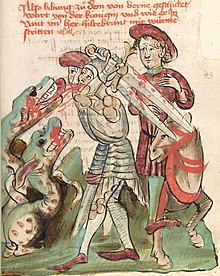

Legends about Theodoric may have existed already shortly after his death in 526. The oldest surviving literature of various Germanic-speaking peoples mentioning the hero Dietrich von Bern, includes the Old English poems Widsith, Deor, and Waldere, the Old High German poem Hildebrandslied, and possibly the Rök runestone. The bulk of the legendary material about Dietrich/Theodoric comes from high and late medieval Holy Roman Empire and is composed in Middle High German or Early New High German. Another important source for legends about Dietrich is the Old Norse Thidrekssaga, which was written using German sources. In addition to the legends detailing events that may reflect the historical Theodoric's life in some fashion, many of the legends tell of Dietrich's battles against dwarfs, dragons, giants, and other mythical beings, as well as other heroes such as Siegfried. Additionally, Dietrich develops mythological attributes such as an ability to breathe fire. Dietrich also appears as a supporting character in other heroic poems such as the Nibelungenlied, and medieval German literature frequently refers and alludes to him.

Poems about Dietrich were extremely popular among the medieval German nobility and, later, the late medieval and early modern patrician classes, but were frequently targets of criticism by persons writing on behalf of the church. Though some continued to be printed in the seventeenth century, most of the legends were slowly forgotten after 1600. They became objects of academic study by the end of the sixteenth century, and were revived somewhat in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, resulting in some stories about Dietrich being popular in South Tyrol, the setting for many of the legends. In particular, the legend of Laurin has continued to be important there, with the Rosengarten group of mountains associated with the legend.

Development in the oral tradition

editDifferences between Dietrich and Theodoric

editDietrich von Bern and Theoderic the Great were usually treated as the same figure throughout the Middle Ages.[1][2] However, the lives of Dietrich von Bern and Theodoric the Great have several important differences. Whereas Theodoric the Great conquered Italy as an invader, Dietrich von Bern is portrayed as exiled from his rightful kingdom in Italy. Also, Dietrich is portrayed as a contemporary of Etzel (Attila the Hun, died 453) and his uncle is the semi-legendary Gothic king Ermenrich (Ermanaric, died 370s).[3] Dietrich is associated with Verona (the Bern of his name) rather than the capital of the historical Theodoric, Ravenna; the connection to Verona is attested since at least the eleventh century in Latin chronicles, beginning with the Annals of Quedlinburg.[4]

Dietrich has a number of mythological features: In the early eleventh-century Waldere he is an enemy of giants,[5] and in later Middle High German texts he also fights against dwarfs and wild men.[6] Even more notable is the fact that multiple texts record Dietrich breathing fire.[7]

Theories

editThe change of Dietrich from invader to exiled ruler trying to reclaim his land is usually explained as following well-known motifs of oral tradition. In effect, Theodoric's conquest has been transformed according to a literary scheme consisting of exile, then return, a story which has a relatively consistent set of recurring motifs throughout world literature.[8] The story told in the heroic tradition is nevertheless meant to convey a particular understanding of the historical event, namely: that Dietrich/Theodoric was in the right when he conquered Italy.[9] Dietrich's exile and repeated failed attempts to reconquer his rightful kingdom, as reported in the later historical poems, may also be a reflection of the destruction of Theodoric's Gothic kingdom by the Byzantine Empire under Justinian I. This is particularly true for the figure of Witege and his betrayal at Ravenna, as told in Die Rabenschlacht.[8] Millet notes, furthermore, that Dietrich is portrayed as without any heirs and that his closest relatives and supporters die in every attempt to reclaim Italy; this too could be a way to explain the short duration of Ostrogothic rule in Italy.[10]

Dietrich's coexistence with Attila and Ermanaric is usually explained by another process active in oral storytelling, synchronization.[11] Dietrich is already associated with an exile among the Huns in the Old High German Hildebrandslied (before 900), and possibly with Etzel/Attila, depending on how one interprets the mentioned huneo druhtin (Hunnish lord).[12] The Hildebrandslied nevertheless still retains Theodoric's historical opponent Odoacer, seemingly showing that Odoacer was the original opponent. It is also possible that the author of the Hildebrandslied altered the report in the oral saga by replacing the unhistorical Emenrich with the historical Odoacer.[13] It is possible that Ermenrich/Ermanaric was drawn into the story due to his historical enmity with the Huns, who destroyed his kingdom. He was also famous for killing his relatives, and so his attempts to kill his kinsman Dietrich make sense in the logic of the oral tradition.[11]

It is possible that Dietrich's association with Verona suggests Longobardic influence on the oral tradition, as Verona was the Longobardic capital for a time, while Ravenna was under the control of the Byzantines.[11] The figure of Dietrich's tutor and mentor Hildebrand is also often thought to derive from Longobardic influence.[14] Heinzle suggests that the exile-saga may have been first told among the Longobards, giving the end of the sixth century as the latest date at which the story may have formed, with the Longobardic conquest of Italy.[11]

Lastly, Dietrich's various mythological and demonic attributes may derive from ecclesiastical criticism of the Arian Theodoric, whose soul, Gregory the Great reports, was dropped into Mount Etna as punishment for his persecution of orthodox Christians. Another notable tradition, first reported in the world chronicle of Otto of Freising (1143–1146), is that Theodoric rode to hell on an infernal horse while still alive.[7] Other traditions record that Theodoric was the son of the Devil. It is unclear whether these negative traditions are the invention of the Church or whether they are a demonization of an earlier apotheosis of the heretical Theodoric. None of the surviving heroic material demonizes Dietrich in this way, however, and presents a generally positive view of the hero.[15]

In the 1980s, Heinz Ritter-Schaumburg proposed that Dietrich von Bern and Theodoric the Great were in fact two distinct historical figures: he argued that Dietrich was an unattested Frankish petty king based at Bonn.[16] Ritter-Schaumburg's book reached a large public and is one of the most popular of all works on Germanic heroic legend published in Germany after World War 2.[17] However, the theses of Ritter-Schaumburg and his followers have been convincingly debunked and are regarded as "pseudo-scientific" by mainstream scholarship.[18][19]

Appearance in early Germanic literature

editScandinavia

editOne of the earliest (quasi-)literary sources about the legend of Theodoric is the Rök Stone, carved in Sweden in the 9th century.[20] There he is mentioned in a stanza in the Eddic fornyrðislag meter:

|

|

The mention of Theodoric (among other heroes and gods of Norse mythology) may have been inspired by a no longer extant statue of an unknown emperor assumed to be Theodoric sitting on his horse in Ravenna, which was moved in 801 A.D. to Aachen by Charlemagne. This statue was very famous and portrayed Theodoric with his shield hanging across his left shoulder, and his lance extended in his right hand: the German clerical poet Walahfrid wrote a poem (De imagine Tetrici) lampooning the statue, as Theodoric was not favorably regarded by the church.[23] Alternatively, Otto Höfler has proposed that Theodoric on the horse may be connected in some way to traditions of Theodoric as the Wild Huntsman (see the Wunderer below); Joachim Heinzle rejects this interpretation.[24]

Germany

editDietrich's earliest mention in Germany is the Hildebrandslied, recorded around 820. In this, Hadubrand recounts the story of his father Hildebrand's flight eastwards in the company of Dietrich, to escape the enmity of Odoacer (this character would later become his uncle Ermanaric). Hildebrand reveals that he has lived in exile for 30 years. Hildebrand has an arm ring given to him by the (unnamed) King of the Huns, and is taken to be an "old Hun" by Hadubrand. The obliqueness of the references to the Dietrich legend, which is just the background to Hildebrand's story, indicates an audience thoroughly familiar with the material. In this work Dietrich's enemy is the historically correct Odoacer (though in fact Theodoric the Great was never exiled by Odoacer), indicating that the figure of Ermanaric belongs to a later development of the legend.[25]

England

editDietrich furthermore is mentioned in the Old English poems Waldere, Deor and Widsith. Deor marks the first mention to Dietrich's "thirty years" (probably his exile) and refers to him, like the Rök stone, as a Mæring.[26] The Waldere makes mention of Dietrich's liberation from the captivity of giants by Witige (Widia), for which Dietrich rewarded Witige with a sword. This liberation forms the plot of the later fantastical poem Virginal and is mentioned in the historical poem Alpharts Tod. Widsith mentions him among a number of other Gothic heroes, including Witige, Heime, the Harlungen and Ermanaric, and in connection with a battle with Attila's Huns. However, the exact relationship between the figures is not explained.[5]

Middle High German Dietrich poems

editDietrich von Bern first appears in Middle High German heroic poetry in the Nibelungenlied. There he appears in the exile situation at Etzel's court that forms the basis for the historical Dietrich poems (see below).[27] Dietrich also appears in the Nibelungenklage, a work closely related to the Nibelungenlied that describes the aftermath of that poem. In the Klage, Dietrich returns from exile to his kingdom of Italy; the poem also alludes to the events described in the later Rabenschlacht.[28] Poems with Dietrich as the main character begin to enter writing afterwards, with the earliest attested being the fantastical poem the Eckenlied (c. 1230).[29] The oral tradition continued alongside this written tradition, with influences from the oral tradition visible in the written texts, and with the oral tradition itself most likely altered in response to the written poems.[30]

The Middle High German Dietrich poems are usually divided into two categories: historical poems and fantastical poems. The former concern the story of Dietrich's fights against Ermenrich and exile at Etzel's court, whereas in the latter he battles against various mythological creatures. This latter group is often called "aventiurehaft" in German, referring to its similarity to courtly romance.[6] Despite connections made between different Dietrich poems and to other heroic cycles such as the Nibelungenlied, Wolfdietrich, and Ortnit, the Dietrich poems never form a closed poetic cycle, with the relationships between the different poems being rather loose: there is no attempt to establish a concrete biography of Dietrich.[30][31][32]

Almost all the poems about Dietrich are written in stanzas. Melodies for some of the stanzaic forms have survived, and they were probably meant to be sung.[33] Several poems are written in rhyming couplets, however, a form more common for courtly romance or chronicles. These poems are Dietrichs Flucht, Dietrich und Wenezlan, most versions of Laurin, and some versions of the Wunderer.[34]

Historical Dietrich poems

editThe historical Dietrich poems in Middle High German consist of Dietrichs Flucht, Die Rabenschlacht, and Alpharts Tod, with the fragmentary poem Dietrich und Wenezlan as a possible fourth.[35] These poems center around Dietrich's enmity with his wicked uncle Ermenrich, who wishes to dispose Dietrich of his father's kingdom. All involve Dietrich's flight from Ermenrich and exile at Etzel's court except Alpharts Tod, which takes place before Dietrich's expulsion, and all involve his battles against Ermenrich, except for Dietrich und Wenezlan, in which he fights against Wenezlan of Poland. All four postdate Dietrich's appearance in the Nibelungenlied.[36] They are called historical because they concern war rather than adventure, and are seen as containing a warped version of Theodoric's life.[37] Given the combination of elements also found in these texts with historical events in some chronicles, and the vehement denunciation of the saga by learned chroniclers, it is possible that these texts ― or the oral tradition behind them — were themselves considered historical.[38][39]

Fantastical poems

editThe majority of preserved narratives about Dietrich are fantastical in nature, involving battles against mythical beings and other heroes. The fantastical poems consist of the Eckenlied, Goldemar, Laurin, Sigenot, Virginal, the Rosengarten zu Worms, and the Wunderer.

These poems are generally regarded as containing newer material than the historical poems, though, as the Old English Waldere's references show, Dietrich was already associated with monsters at an early date.[40] Many of the poems show a close connect to the Tyrol, and connections between them and Tyrolean folklore are often speculated upon, even in cases where the text itself clearly originated in a different German speaking area.[41] Most of the poems seem to take place prior to Dietrich's exile, with the later traitors Witige and Heime still members of Dietrich's entourage, though not all: the Eckenlied prominently features references to the events of Die Rabenschlacht as already having taken place.[42]

Different exemplars of the fantastical poems often show a huge degree of variation from each other (Germ. Fassungsdivergenz), a trait not found in the historical poems. Most fantastical poems have at least two versions containing substantial differences in the narrative, including inserting or removing entire episodes or altering the motivation of characters, etc.[43] The scholar Harald Haferland has proposed that the differences may come from a practice of reciting entire poems from memory, using set formula to fill in lines and occasionally adding or deleting episodes. Haferland nevertheless believes that the poems were likely composed as written texts, and thus periodically new versions were written down.[44]

The majority of the fantastical poems can be said to follow two basic narrative schemes, in some cases combining them: the liberation of a woman from a threatening legendary being, and the challenging of Dietrich to combat by some antagonist.[45] The combinations of these schemes can at times lead to narrative breaks and inconsistencies in character motivation.[46]

Related works

editOrtnit and Wolfdietrich

editThe two heroic epics Ortnit and Wolfdietrich, preserved in several widely varying versions, do not feature Dietrich von Bern directly but are strongly associated with the Dietrich cycle, and most versions share the strophic form of the Hildebrandston. These two poems, along with Laurin and Rosengarten, form the core of the Strassburg Heldenbuch and the later printed Heldenbücher,[47] and are the first of the ten Dietrich poems in the Dresden Heldenbuch.[48] In the Ambraser Heldenbuch they close the collection of heroic epics, which starts with Dietrichs Flucht and the Rabenschlacht.[49]

The basis for the association is the identification of Wolfdietrich as the grandfather of Dietrich. This connection is attested as early as 1230 in the closing strophe of Ortnit A,[50] is perpetuated by the inclusion of truncated versions of Ortnit and Wolfdietrich in Dietrichs Flucht among the stories of Dietrich's ancestors,[32] and is repeated in the Heldenbuch-Prose of the 15th and 16th centuries, where Ortnit and Wolfdietrich are placed at the beginning of the Dietrich cycle.[51] Scholars have sometimes supposed that Wolfdietrich tells the story of legends about Dietrich that somehow became disassociated from him.[52] In the Old Norse Thidreksaga, Thidrek (Dietrich) plays Wolfdietrich's role as the avenger of Hertnid (Ortnit), which may suggest that the two heroes were once identical.[53]

A further link is Dietrich's golden suit of impenetrable armour. This was originally received by Ortnit from his natural father, the dwarf Alberich. Ortnit is killed by a dragon who, being unable to kill him through his armour, sucks him out of it. When Wolfdietrich later avenges Ortnit by killing the dragon, he takes possession of the abandoned armour, and after his death it remains in the monastery to which he retired. In the Eckenlied we are told that the monastery later sold it to Queen Seburg for 50,000 marks, and she in turn gives it to Ecke. When Dietrich later defeats the giant, the armour finally passes into Dietrich's possession.[54]

Biterolf und Dietleib

editBiterolf and Dietleib is a heroic epic transmitted in the Ambraser Heldenbuch. It is closely related to the Rosengarten zu Worms. It tells the story of the heroes King Biterolf of Toledo and his son Dietleib, relatives of Walter of Aquitaine. The two heroes live at Etzel's court and receive Styria as a reward for their successful defense of Etzel's kingdom. In the second half of the work, there is a battle against the Burgundian heroes Gunther, Gernot, and Hagen at Worms, in which Dietleib avenges an earlier attempt by Hagen to prevent him from crossing the Rhine. Like the Rosengarten, Dietrich is featured fighting Siegfried, but he plays no larger role in the epic.[55]

Jüngeres Hildebrandslied

editThe Jüngeres Hildebrandslied ("Younger Lay of Hildebrand") is a fifteenth-century heroic ballad, much like Ermenrichs Tod. Dietrich plays only a small role in this poem; it is an independent version of the same story found in the Old High German Hildebrandslied, but with a happy ending.

Ermenrichs Tod

editErmenrichs Tod ("The Death of Ermenrich") is a garbled Middle Low German heroic ballad that relates a version of the death of Ermenrich that is similar in some ways to that portrayed in the story of Jonakr's sons and Svanhild, but at the hands of Dietrich and his men.

Heldenbücher

editThe Heldenbücher ("Books of Heroes", singular Heldenbuch) are collections of mainly heroic poems, in which those of the Dietrich cycle form a major constituent. In particular, the printed Heldenbücher, dating from the late 15th to the late 16th centuries, demonstrate the continuing appeal of the Dietrich tales, particularly the fantastical poems.[56] Generally, the printed Heldenbücher show a tendency to reduce the texts of the poems they collect in length: none of the longest Dietrich poems (Dietrichs Flucht, Rabenschlacht, Virginal V10) made the transition into print.[57] Other longer Dietrich poems, such as the Sigenot and the Eckenlied, were printed independently, and remained popular even longer than the Heldenbuch—the last printing of Sigenot was in 1661![58]

Although not a Heldenbuch in the sense described above—the term originally included any collection of older literature—the Emperor Maximilian I was responsible for the creation of one of the most expensive and historically important manuscripts containing heroic poetry, the Ambraser Heldenbuch.[59]

Heldenbuch-Prosa

editAccording to the Heldenbuch-Prosa, a prose preface to the manuscript Heldenbuch of Diebolt von Hanowe from 1480 and found in most printed versions, Dietrich is the grandson of Wolfdietrich and son of Dietmar. During her pregnancy, Dietrich's mother was visited by the demon Machmet (i.e. Mohammed imagined as a Muslim god), who prophecies that Dietrich will be the strongest spirit who ever lived and will breathe fire when angry. The devil (Machmet?) then builds Verona/Bern in three days.[60] Ermenrich, here imagined as Dietrich's brother, rapes his marshal Sibiche's wife, whereupon Sibiche decides to advise Ermenrich to his own destruction. Thus he advises Ermenrich to hang his own nephews. Their ward, Eckehart of Breisach, informs Dietrich, and Dietrich declares war on Ermenrich. Ermenrich, however, captures Dietrich's best men, and to ransom them, Dietrich goes into exile. He ends up at Etzel's court, who gives Dietrich a large army that reconquers Verona. However, once Dietrich had fought at the rose garden against Siegfried, slaying him. This causes Kriemhild, who after Etzel's wife Herche's death, marries the Hun, to invite all the heroes of the world to a feast where she causes them to kill each other. Dietrich kills Kriemhild in revenge. Later there is a massive battle at Verona, in which all the remaining heroes except Dietrich are killed.[61] At this a dwarf appears to Dietrich and, telling him that "his kingdom is no longer of this world," causes him to disappear. And no one knows what has happened to him.[62]

The attempts to connect the heroic age with divine order and to remove Dietrich's demonic qualities are probably meant to deflect ecclesiastical criticism of heroic poetry. For instance, the author clearly attempts to hide negative characteristics of Dietrich, as with the Machmet-prophesy, which probably rests on the idea of Dietrich as the son of the Devil (as claimed by some in the church) and changing Dietrich's ride to hell into a positive event – the dwarf quotes John 18,36 when he takes Dietrich away.[62]

Scandinavian works

editThe Poetic Edda

editDietrich, as Thiodrek (Þjóðrekr), appears as an exile at the court of Atli (the Norse equivalent of Etzel) in two songs recorded in the so-called Poetic Edda. The most notable of these is Guðrúnarkviða III, in which Gudrun—the Old Norse equivalent of the German Krimehilt—is accused of adultery with Thiodrek by one of Atli's concubines, Herkja. Gudrun must perform an ordeal of hot water, in which she clears her name. After this, Herkja is killed. In Guðrúnarkviða II, Thiodrek and Gudrun recount the misfortunes that have befallen them.[63] Thiodrek's presence in both songs is usually interpreted as coming from the influence of German traditions about Dietrich.[64] Herkja's name is an exact linguistic equivalent of the name of Etzel's first wife in the German Dietrich and Nibelungen cycle, Helche.[65] The poems also include the figure of Gudrun's mother, Grimhild, whose name is the linguistic equivalent of the German Kriemhilt and who takes on the latter's more villainous role.[66] Most likely these two poems only date to the thirteenth century.[65]

Thidrekssaga

editThe Scandinavian Þiðreks saga (also Þiðrekssaga, Thidreksaga, Thidrekssaga, Niflunga saga or Vilkina saga) is a thirteenth-century Old Norse chivalric saga about Dietrich von Bern.[67] The earliest manuscript dates from the late 13th century.[68] It contains many narratives found in the known poems about Dietrich, but also supplements them with other narratives and provides many additional details. The text is either a translation of a lost Middle Low German prose narrative of Dietrich's life, or a compilation by a Norwegian author of German material. It is not clear how much of the source material might have been orally transmitted and how much the author may have had access to written poems. The preface of the text itself says that it was written according to "tales of German men" and "old German poetry", possibly transmitted by Hanseatic merchants in Bergen.[67] It is known that the author of the "Heldenbuch-Prosa" did not have access to the Þiðreks saga.[69]

At the center of the Thidrekssaga is a complete life of Dietrich. In addition to the life of Dietrich, various other heroes' lives are recounted as well in various parts of the story, including Attila, Wayland the Smith, Sigurd, the Nibelungen, and Walter of Aquitaine. The section recounting Dietrich's avenging of Hertnit seems to have resulted from a confusion between Dietrich and the similarly named Wolfdietrich.

Most of the action of the saga has been relocated to Northern Germany, with Attila's capital at Susat (Soest in Westphalia) and the battle described in the Rabenschlacht taking place at the (nonexistent) mouth of the Moselle to the sea.[70]

Ballads

editNumerous ballads about Dietrich are attested in Scandinavia, primarily in Denmark, but also in Sweden and the Faroes.[71] These texts seem to derive primarily from the Thidrekssaga, but there are signs of the use of German texts, such as the Laurin,[72] which was translated into Danish, probably in the 1400s.[73]

One of the most notable of the Danish ballads is Kong Diderik og hans Kæmper (King Dietrich and his Warriors, DgF 7) which is attested from the 16th century onwards, and is one of the most common ballads to be recorded in Danish songbooks.[74] This is actually most often found in both Danish and Swedish sources as two separate ballads with different refrains; the two ballads tell stories that closely, but not exactly, mirror episodes in the Didrik Saga where Didrik and his warriors travel to Bertanea / Birtingsland to fight against a King Ysung / Isingen.[71][75] The first ballad, known in Swedish as Widrik Werlandssons Kamp med Högben Rese (Widrik Werlandsson's Fight with the Long-legged Troll, SMB 211, TSB E 119), tells of the journey to Birtingsland, and a fight with a troll in a forest on the way. The second, known in Swedish as Tolv Starka Kämpar (Twelve Strong Warriors, SMB 198, TSB E 10) tells of a series of duels between the youngest of Didrik's warriors and the formidable Sivard (Sigurd).

The Danish ballad Kong Diderik og Løven (King Didrik and the Lion, DgF 9, TSB E 158) for most of its narrative closely follows an episode from near the end of the Didrik Saga, telling how Didrik intervenes in a fight between a lion and a dragon.[71] This was also one of the most common ballads to be recorded in Danish songbooks; it is not preserved in Swedish sources.[74]

Another Danish ballad, Kong Diderik i Birtingsland (King Dietrich in Birtingsland, DgF 8, TSB E 7), is related to Kong Diderik og hans Kæmper, but it follows the Didrik Saga less closely.[71]

Legacy

editMedieval and early modern

editThe popularity of stories about Dietrich in Germany is already attested in the Annals of Quedlinburg.[76] The quality of the surviving late medieval manuscripts and the choice to decorate castle rooms with scenes from the poems all point to a noble audience, even though there are also reports of the poems being read or sung at town fairs and in taverns.[77] As one example, the Emperor Maximilian I's interest in heroic poetry about Dietrich is well documented. Not only was he responsible for the Ambraser Heldenbuch, he also decorated his planned grave monument with a large statue of Dietrich/Theodoric, next to other figures such as King Arthur.[78]

Although the nobility maintained its interest in heroic poetry into the sixteenth century, it is also clear that the urban bourgeoisie of the late Middle Ages formed a growing part of the audience for the Dietrich poems, likely in imitation of the nobility.[79] Heroic ballads such as Ermenrichs Tod, meanwhile, lost much of their noble associations and were popular in all societal classes.[80] Beginning in the fourteenth century, many of the Dietrich poems were also used as sources for carnival plays with an obviously bourgeois audience.[81] In the sixteenth century, the public for the poems seems to have become primarily bourgeois, and printed Heldenbücher rather than the oral tradition become the primary point of reference for the poems.[82] The poems that had not been printed were no longer read and were forgotten.[83] The Sigenot continued to be printed in the seventeenth century, the Jüngeres Hildebrandslied into the eighteenth, however, most of the printings of materials about Dietrich had ceased by 1600. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century folklorists were unable to find any living oral songs about Dietrich or other heroes in Germany as they could in some other countries, meaning that the oral tradition must have died before this point.[84]

Despite, or because of, its popularity among many sectors of society, including members of the church, the Dietrich poems were frequent targets of criticism.[85] Beginning with the universal chronicle of Frutolf of Michelsberg (eleventh century), writers of chronicles began to notice and object to the chronology of Dietrich/Theodoric being a contemporary of Ermanaric and Attila. Frutolf of Michelsberg, who developed a critical view of history and awareness of anachronism, pointed out that "some songs as 'vulgar fables' made Theoderic the Great, Attila and Ermanaric into contemporaries, when any reader of Jordanes knew that this was not the case". He suggests, that "either Jordanes or the Saga is wrong or the Saga is about another Ermanarich or another Dietrich".[2]

The anonymous author of the German Kaiserchronik (c.1150) vehemently attacks this chronological impossibility as a lie. His insistence is perhaps a reflection of the strong believe of the historical truth of these stories among his target audience.[86] Hugo von Trimberg, meanwhile, in his didactic poem Der Renner (c. 1300) accuses some women of crying more for Dietrich and Ecke than for Christ's wounds, while a fifteenth-century work complains that the laypeople think more about Dietrich von Bern than their own salvation.[87] In the sixteenth century, despite continued criticism, there is evidence that preachers, including Martin Luther, frequently used stories about Dietrich von Bern as a way to catch their audience's interest, a not uncontroversial practice.[88] Writers from Heinrich Wittenwiler to the German translator of Friedrich Dedekind's Grobianus associated the poems with uncouth peasants, whether or not they actually formed part of the poems' audiences.[89]

Modern age

editScholarly reception of the Dietrich poems, in the form of the Heldenbuch, began as early as the sixteenth century. The Baroque poets and scholars Martin Opitz and Melchior Goldast made use of the Heldenbuch as a convenient source of Middle High German expressions and vocabulary in their editions of medieval texts.[83] Another notable example is the Lutheran theologian and historian Cyriacus von Spangenberg. In his Mansfeldische Chronik (1572), he explained that songs had about Dietrich/Theodoric had been composed for real historical occasions, so that they might not be forgotten, but clothed in allegory. He based this opinion on the report of Tacitus in Germania that the ancient Germans only recorded their history in songs. In Spangenberg's interpretation, the dwarf king Laurin's cloak of invisibility, for instance, becomes a symbol for Laurin's secrecy and sneakiness.[90] In his Adels Spiegel (printed 1591-1594), Cyriacus interprets the stories about Dietrich as examples for ideal noble behavior, and continues his allegorical interpretations, stating that the dragons and giants represent tyrants, robbers, etc., while the dwarfs represent the peasantry and bourgeoisie, etc.[91] This tradition of interpretation would continue into the eighteenth century, when Gotthold Ephraim Lessing interprets the poems of the Heldenbuch in a very similar fashion, and as late as 1795, Johann Friedrich Schütze argued that the poems were allegories for medieval historical events.[92]

The medieval poems about Dietrich never attained the same status as the Nibelungenlied among nineteenth-century enthusiasts for the German past, despite repeated attempts to reanimate the material through reworkings and retellings. The most ambitious of these was by Karl Simrock, the translator of the Nibelungenlied, who sought to write a new German epic, composed in the "Nibelungenstanza", using material from the Thidrekssaga and select poems of the Dietrich cycle. He called his project the Amelungenlied (song of the Amelungs). Despite a warm reception among connoisseurs, the poem was never popular. The poem remains unpopular and unknown today, at least partially due to its strong nationalistic tone.[93]

Of all the Dietrich poems, the Laurin was most frequently rewritten and reimagined during the nineteenth-century, and it is the poem with the greatest currency today. The reworkings, which included longer poems and pieces for the theater, frequently connected Laurin to elements of other Dietrich poems, especially the Virginal.[94] This led to the Laurin, together with the reimagined Virginal, attaining something of the status of folktales in Tyrol and South Tyrol. Much of the credit for the continued interest in Dietrich and Laurin in Tyrol can be given to the journalist and saga-researcher Karl Felix Wolff.[95] In 1907, the city of Bozen (Bolzano) in South Tyrol erected a Laurin fountain, depicting Dietrich wrestling Laurin to the ground.[96]

Notes

edit- ^ Lienert 2008, p. 3.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 21.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Lienert 2008, pp. 3, 11–12.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 17.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Heinzle 1999, p. 8.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 6.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 36-37.

- ^ a b c d Heinzle 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Haubrichs 2004, p. 525.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Frederick Norman, "Hildebrand and Hadubrand", in Three Essays on the 'Hildebrandslied' , London 1973, p. 47.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Ritter-Schaumburg; Heinz (1981). Die Nibelungen zogen nordwärts. Munich: Herbig. ISBN 3442113474. Ritter-Schaumburg; Heinz (1982). Dietrich von Bern. König zu Bonn. Munich: Herbig. ISBN 3776612274.

- ^ Kragl 2010, p. XXIII.

- ^ Goltz 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Kragl 2010, p. XVII.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 15.

- ^ Entry "Ög 136 in the Scandinavian Runic-text Database - Rundata.

- ^ Wills, Tarrin, ed. (21 July 2019). "Ög 136 (Ög136) - Rök stone". Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 16.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 11–12.

- ^ An Old English poem called Deor's Lament refers to several legendary tribulations all of which passed in time, including those of the Maerings who were ruled over by one Theodric. "Theodric ruled / for thirty winters / the city of the Mærings."

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 29

- ^ a b Millet 2008, pp. 352–354.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 334–335.

- ^ a b Millet 2008, p. 401.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 64-67.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, p. 17.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 23–27.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 58.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 33–34.

- ^ See Paulus Bernardus Wessels, "Dietrichepik und Südtiroler Erzählsubstrat," in Zeitschrift für deutsche Philologie 85 (1966), 345-369

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 34.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 333–334.

- ^ Haferland 2004.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 358.

- ^ Miklautsch 2005, pp. 63, 69–70.

- ^ Miklautsch 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Miklautsch 2005, p. 40.

- ^ Miklautsch 2005, p. 89.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 46.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 394–395.

- ^ Haferland 2004, p. 374.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Hoffmann 1974, p. 203.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 420.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 45.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 47.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 48.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 35-36.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 305.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 37.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 305–306.

- ^ a b The article Didrik av Bern in Nationalencyklopedin (1990).

- ^ Helgi Þorláksson, 'The Fantastic Fourteenth Century', in The Fantastic in Old Norse/Icelandic Literature; Sagas and the British Isles: Preprint Papers of the Thirteenth International Saga Conference, Durham and York, 6th–12th August, 2006, ed. by John McKinnell, David Ashurst and Donata Kick (Durham: Centre for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, Durham University, 2006), http://www.dur.ac.uk/medieval.www/sagaconf/sagapps.htm Archived 22 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b c d Svend Grundtvig, Danmarks Gamle Folkeviser, vol. 1, 1853

- ^ Heinzle, Einführung, 56

- ^ "Dværgekongen Laurin (Sth. K47; lemmatiseret)". tekstnet.dk.

- ^ a b "Visernes top-18". duds.nordisk.ku.dk. 23 October 2006.

- ^ A. I. Arwidsson, Svenska Fornsånger, 1834-1842

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 19.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 20, 31.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 31.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 415, 422.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 472.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 477–478.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 483–484.

- ^ a b Heinzle 1999, p. 195.

- ^ Millet 2008, p. 492.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 20.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 22.

- ^ Jones 1952, p. 1096.

- ^ Flood 1967.

- ^ Jones 1952.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Millet 2008, pp. 491–492.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 197.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Altaner 1912, pp. 68–78.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Heinzle 1999, pp. 162.

Translations of individual texts

editEnglish

- The Saga of Thidrek of Bern. Translated by Haymes, Edward R. New York: Garland. 1988. ISBN 0-8240-8489-6.

- The Saga of Didrik of Bern. Translated by Cumpstey, Ian. 2017. ISBN 978-0-9576120-3-7. (translations of the Swedish Didrik Saga and the Danish Laurin)

German

- Die Thidrekssaga. Translated by von der Hagen, Friedrich. Sankt-Goar: Otto Reichl. 1989 [1814].

- Die Geschichte Thidreks von Bern. Translated by Erichsen, Fine. Diederichs. 1924.

- Die Didriks-Chronik oder die Svava: das Leben König Didriks von Bern und die Niflungen. Translated by Ritter-Schaumburg, Heinz. Der Leuchter. 1989. ISBN 3-87667-102-7. (translation of the Swedish Didrik saga)

- Die Aventiurehafte Dietrichepik : Laurin und Walberan, der Jüngere Sigenot, das Eckenlied, der Wunderer. Translated by Tuczay, Christa. Göppingen: Kümmerle. 1999. ISBN 3874528413.

Modern retellings

editEnglish

- McDowall, M. W. (1884). Anson, W. S. W. (ed.). Epics and Romances of the Middle Ages, Adapted from the Work of Dr. W. Wägner (2nd ed.). London: Sonnenschein. pp. 130–226.

- Mackenzie, Donald A. (1912). Teutonic Myth and Legend: An Introduction to the Eddas & Sagas, Beowulf, the Nibelungenlied, etc. Myth and legend in literature and art. London: Gresham. pp. 404–453.

- Sawyer, Ruth; Mollès, Emmy (1963). Dietrich of Berne and the Dwarf King Laurin: Hero Tales of the Austrian Tirol. New York: The Viking Press.

German

- Simrock, Karl (1843). Das Heldenbuch Band 4: Des Amelungenliedes erster Theil: Wieland der Schmied; Wittich Wielands Sohn; Ecken Ausfahrt. Stuttgart and Tübingen: Cotta. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Simrock, Karl (1846). Das Heldenbuch Band 5: Des Amelungenliedes zweiter Theil: Dietleib; Sibichs Verrath. Stuttgart and Tübingen: Cotta. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Simrock, Karl (1849). Das Heldenbuch Band 6: Des Amelungenliedes dritter Theil: Die beiden Dietriche; Die Rabenschlacht; Die Heimkehr. Stuttgart and Tübingen: Cotta. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Fröhlich, W. (1936). Dietrich von Bern and the Tannhäuser. Cambridge University Press. (German text intended for language learners)

References

edit- Altaner, Bruno (1912). Dietrich von Bern in der neueren Literatur. Breslau: Hirt.

- Flood, John L. (1967). "Theologi et Gigantes". Modern Language Review. 62 (4): 654–660. doi:10.2307/3723093. JSTOR 3723093.

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700-1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 9780198157182.

- Goltz, Andreas (2008). Barbar – König – Tyrann: Das Bild Theoderichs des Großen in der Überlieferung des 5. bis 9. Jahrhunderts. de Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110210125.

- Grimm, Wilhelm (1867). Die Deutsche Heldensage (2nd ed.). Berlin: Dümmler. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Haferland, Harald (2004). Mündlichkeit, Gedächtnis und Medialität: Heldendichtung im deutschen Mittelalter. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3-525-20824-3.

- Haubrichs, Wolfgang (2004). ""Heroische Zeiten?": Wanderungen von Heldennamen und Heldensagen zwischen den germanischen gentes des frühen Mittelalters". In Nahl, Astrid von; Elmevik, Lennart; Brink, Stefan (eds.). Namenwelten: Orts- und Personennamen in historischer Sicht. Berlin and New York: de Gruyter. pp. 513–534. ISBN 3110181088.

- Haymes, Edward R.; Samples, Susan T. (1996). Heroic legends of the North: an introduction to the Nibelung and Dietrich cycles. New York: Garland. ISBN 0815300336.

- Heinzle, Joachim (1999). Einführung in die mittelhochdeutsche Dietrichepik. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-015094-8.

- Heusler, Andreas (1913–1915). "Dietrich von Bern". In Hoops, Johannes (ed.). Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). Vol. 1. Strassburg: Trübner. pp. 464–468. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Hoffmann, Werner (1974). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldendichtung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. ISBN 3-503-00772-5.

- Jiriczek, Leopold Otto (1902). Northern Hero-Legends, translated by M. Bentinck Smith. London: J. M. Dent.

- Jones, George Fenwick (1952). "Dietrich von Bern as a Literary Symbol". PMLA. 67 (7): 1094–1102. doi:10.2307/459961. JSTOR 459961.

- Kragl, Florian (2007). "Mythisierung, Heroisierung, Literarisierung: Vier Kapitel zu Theoderich dem Großen und Dietrich von Bern". Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur. 129: 66–102. doi:10.1515/BGSL.2007.66. S2CID 162336990.

- Lienert, Elisabeth, ed. (2008). Dietrich-Testimonien des 6. bis 16. Jahrhunderts. Texte und Studien zur mittelhochdeutschen Heldenepik, 4. Berlin: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3484645042.

- Kragl, Florian (2010). Nibelungenlied und Nibelungensage: Kommentierte Bibliographie 1945-2010. de Gruyter. doi:10.1524/9783050059655.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2010). Die 'historische' Dietrichepik. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-025131-9.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.

- Miklautsch, Lydia (2005). Montierte Texte - hybride Helden. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-018404-4. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.

- Sandbach, F.E. (1906). The Heroic Saga-Cycle of Dietrich of Bern. London: David Nutt. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- Voorwinden, Norbert (2007). "Dietrich von Bern: Germanic Hero or Medieval King? On the Sources of Dietrichs Flucht and Rabenschlacht" (PDF). Neophilologus. 91 (2): 243–259. doi:10.1007/s11061-006-9010-3. S2CID 153590793.

External links

edit- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.