The siege of Basing House near Basingstoke in Hampshire, was a Parliamentarian victory late in the First English Civil War. Whereas the title of the event may suggest a single siege, there were in fact three major engagements. John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester owned the House and as a committed Royalist garrisoned it in support of King Charles I, as it commanded the road from London to the west through Salisbury.

| Siege of Basing House | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the First English Civil War | |||||||

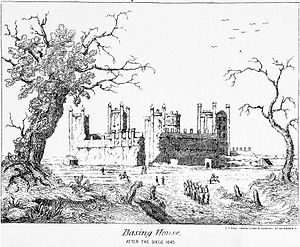

Basing House after the siege | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester | Oliver Cromwell | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | 7,000+ | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400 killed | 2,000 killed | ||||||

The first engagement was in November 1643, when Sir William Waller at the head of an army of about 7,000 attempted to take Basing House by direct assault. After three failed attempts it became obvious to him that his troops lacked the necessary resolve, and with winter fast approaching Waller retreated back to a more friendly location.

Early in 1644 the Parliamentarians attempted to arrange the secret surrender of Basing House with Lord Edward Paulet, the Marquess of Winchester's younger brother, but the plot was discovered.

Parliamentary forces continued the siege by garrisons on the static approaches to Basing House to stop the Royalists foraging and relief convoys getting through. Then on 4 June 1644, Colonel Richard Norton using Parliamentary troops from the Hampshire garrisons closely invested Basing House and attempted to starve the garrison into submission. This siege was broken on 12 September 1644 when a relief column under the command of Colonel Henry Gage broke through parliamentary lines. Having resupplied the garrison he did not tarry but left the next day and returned to Royalist lines. The Parliamentarians reinvested the place but by the middle of November threatened by a Royalist army and his besieging force decimated by disease Waller ended the investment. Five days later on 20 November Gage arrived with fresh supplies.

The final siege took place in October 1645. Oliver Cromwell joined parliamentary forces besieging the House with his own men and a siege train of heavy guns. They quickly breached the defences and on the morning of 14 October 1645 the House was successfully stormed. As the garrison had refused to surrender before the assault—during the two years of the siege, upwards of 2,000 Parliamentarians were slain.[1]—the attackers, who had little sympathy for those they perceived to be Roman Catholics, killed about a quarter of the 400 members of the garrison, including ten priests (six of whom were killed during the assault and four others held to be executed later).

During the assault the House caught fire and was badly damaged. What remained was "totally slighted and demolished" by order of Parliament, with the stones of the House offered free to anyone who would cart them away.

Prelude

editSir William Paulet, created Baron St. John of Basing by Henry VIII, and Earl of Wiltshire and Marquess of Winchester by Edward VI, "converted Basing House from a feudal castle into a magnificent and princely residence."

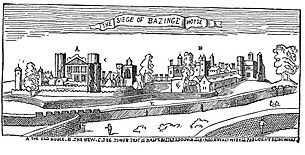

A good description of the House as it stood before the siege is found in the Marquess's own Diary. Basing House stood on a rising ground, its form circular, encompassed with brick ramparts lined with earth, and a very deep ditch but dry. The lofty Gate-house, with four Turrets, looking Northwards, on the right hand thereof, without the ditch, a goodly building containing two fair courts; before them was the Grange, severed by a wall and common road, etc. Some idea of the magnitude of the place may be found when it is remembered that from a survey made in 1798 the area of the works including gardens and entrenchments, covered about fourteen and a half acres.[2]

The siege, which has rendered the name of Basing House famous, commenced in August, 1643, when it was held for the King by John Paulet, 5th Marquess of Winchester, who retired hither in the vain hope that "integrity and privacy might have here preserved his peace" but in this he was deceived, and was compelled to stand upon his guard, which with his gentlemen armed with six muskets he did so well that twice he repulsed the attempts of the "Roundheads" to take possession. On 31 July 1643, the King, on the petition of the Marquess, sent 100 musketeers, under Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Peake, to form a garrison. Within a few hours of the arrival of these troops, colonels Harvey and Richard Norton attempted a surprise attack, but were beaten off and retreated the same night to Farnham.[3]

The Marquess, who had taken out a commission as Colonel and Governor, at once set to work with the aid of Colonel Peake (appointed Governor of the House under the Marquess) directing Peake's troops, and a reinforcement of 150 men, to strengthen the works, as rumours had reached him that Sir William Waller was marching towards the House with a strong force.[3][a]

Among the inhabitants of the House during the siege were a number of notable men of letters and the arts, some of them were Royalist soldiers and others as Royalist refugees from London. William Faithorne, a pupil of Robert Peake's father was one of the besieged, and has left a clever satirical engraving of Hugh Peters (an enemy at the gate), as well as many other fine portraits. Another, still more famous engraver in the House, namely Wenceslaus Hollar, (see Virtue's Life of him) engraved a portrait of the Marquess. Other inmates were Inigo Jones, the great architect, and Thomas Fuller, author of the "Worthies of England" who is said to have been engaged on that work at the very time of the Siege, and to have been much interrupted by the noise of cannon.[5] Another man of letters found shelter at Basing House, where he lost his life, viz. Lieut.-Colonel Thomas Johnson, M.D., the editor of Gerard's Herbal, and author of several botanical works.[6] Captain William Robbins, a prominent comic actor in the Jacobean and Caroline eras, was killed during the siege.[7]

There is little doubt that a scarcity of ammunition, as well as of provisions, was the cause of some embarrassment to the Marquess in his defence of the House. In the first year of the siege (12 October 1643) the King issued a warrant to the following effect :

Charles R. To our right trusty and well-beloved Henry, Lord Percy, general of our ordnance for the present expedition. Our will and pleasure is, that you forthwith take order for sending to the Marquess of Winchester's House of Basing ten barrels of powder with match and bullets proportionable. And this shall be your warrant. Given at our Court at Oxford this twelfth day of October, 1643.[8]

This having been communicated to the Marquess he wrote as follows:

To the right Honorable the Lord Percy, General of his Majesty's ordnance at Court.

My Lord. Understanding by a letter from Mr. Secretary Nicholas, that his Majesty hath given a warrant for the issuing out of your magazine ten barrels of powder and double proportion of match, I therefore desire your Lordship to command carts for the conveying of the said powder from Oxford to this garrison, standing not only in great want of the same, but also daily expecting the enemy's approach, who are now at Farnham with a considerable force of horse and foot. I have dispatched this messenger who will attend the expedition. And if any arms have been brought into the magazine, I desire your favour in the furtherance of 100 muskets to be sent with this conveyance, and in so doing yon shall infinitely oblige, my Lord, your Lordship's most affectionate kinsman and humble Servant, Winchester.

Basing Castle, 2nd November 1643.[8]

Sir William Waller, who was more active than the Earl of Essex, was at that time the favourite of those in the Long Parliament who believed that greater energy would produce more successful results. On 4 November 1643 he placed at the head of a new South-Eastern Association, comprising the counties of Kent, Surrey, Sussex, and Hampshire.[9] What supplies could be procured were hurried forward to his headquarters, and on 7 November he set out to besiege Basing House—Loyalty House, as its owner loved to call it—the fortified mansion of the Catholic John, Marquess of Winchester, now garrisoned by a party of London Royalists. Basing House commanded the road to the west through Salisbury, as Donnington Castle, now garrisoned for the King, commanded the more northern road to the west through Newbury.[10]

First siege

editOn 6 November 1643 Waller, with 7,000 horse and foot surrounded the House, where they remained for nine days, during which time they made three ineffectual attempts to carry the place by storm, but were each time beaten off with heavy losses. During these assaults only two of the garrison were slain.[11]

Waller's first attack upon Basing House was frustrated by a storm of wind and rain. His second attempt came to nothing from a cause far more ominous of disaster. His troops had long remained unpaid, and a mutinous spirit was easily aroused amongst them. On 12 November a Westminster regiment refused to obey orders, and two days later the London trained bands, bidden to advance to the assault, shouted "Home! home!", and deserted in a body.[12] It was impossible to continue the siege under such conditions, and Waller was compelled to retreat to Parliamentary controlled Farnham.[13] At this juncture the King's troops, under Lord Hopton, marched to the House and assisted in strengthening the works.[11]

Nothing of importance appears to have occurred during the winter months which followed. The House was still short of arms and on 2 February 1644 the King despatched a second letter containing a warrant for the same amount of "powder and match, proportionable" as before, together with sixty "brown bills". A third letter from the King, similarly addressed, dated from Oxford, 13 May 1644, gave orders for a thousand weight of match and forty muskets, "to be delivered to such as shall be appointed by the Marquess of Winchester to receive the same, for the use of our garrison at Basinge Castle".[8]

1644 plot

editIn early 1644 Basing House was in the custody of Lord Charles Paulet, the brother of the Marquess of Winchester, and it was believed in London that Paulet was prepared to betray his trust.[b]

Amongst those who took part in the council of war was Sir Richard Grenville, a younger brother of Sir Bevil. In the historian S.R. Gardiner's opinion "A selfish and unprincipled man, [who] had gone through the evil schooling of the Irish War",[15] and, falling into the hands of the Parliamentarians upon his landing at Liverpool, he had declared himself willing to embrace their cause. His military experience gained him the appointment of lieutenant-general of Waller's horse. He was not a man to feel at home in an atmosphere of Puritanism, and on 3 March 1644 he fled to Oxford, carrying with him the secret of Paulet's treachery. Grenvile's name was attached with every injurious epithet to a gallows in London.[c] While at Oxford he was regarded as a pattern of loyalty.

Paulet was arrested and sent before a court-martial. Eventually, however, he received a pardon from the King, who, as Gardiner conjectured, was unwilling to send the brother of so staunch a supporter as the Marquess of Winchester to an ignominious death.[15]

Second siege

editAn extract from a letter sent by Waller to Hopton, who had been his companion in arms abroad, relative to the part he was to take in these wars, may to some extent account for his want of success in his three attempts upon Basing House, he says:

That great God, who is the searcher of all hearts, knows with what a sad fear I go upon this service, and with what a perfect hate I detest a war without an enemy, but I took upon it as an opus Domini, which is eno' to silence all passion in one.[16]

In the spring of 1644, the Parliamentarians, having met with so many reverses in trying to take the place by storm, set themselves to the task of starving the garrison out, and for this purpose strong bodies of their troops were quartered at Farnham, Odiham, Greywell, and Basingstoke, who patrolled the adjacent country to prevent the taking in of provisions.[16]

Matters appear to have continued in this condition until 4 June, when Norton came a second time upon the scene with a force drawn from the neighbouring Parliamentarian garrisons, and closely invested the place, he having, by means of information received from a deserter, two days previously defeated a party of the besieged at Odiham. This force consisted at first of a regiment of horse (his foot not having arrived), and were quartered in Basingstoke at night, all avenues by which food could be taken into the House being closely watched.[17]

On 11 June, Colonel Morley's regiment of six colours of blues, Sir Richard Onslow's of five of red, with two of white from Farnham, and three fresh troops of horse, fetched in by Norton's regiment, drew up before the House, on the south towards Basingstoke, and in the evening some were sent into quarters at Sherfield and others to Andwell and Basingstoke.[18]

On 17 June the church was occupied and fortified by the attacking force, who managed to shoot two of the defenders. The garrison of the House being few in number, the Marquess decided to divide them into three parties, two of which should be constantly on duty. To each captain and his company was assigned a particular guard, and the quarters of the garrison were given to Major Cufaude, Major Langley, and Lieutenant-Colonel Rawdon, while Lieutenant-Colonel Peake had charge of the guns and the reserve. All these officers acted as captains of the watch, except Rawdon, who was excused on account of his great age.[19]

On 18 June a sally was made from the House, and several buildings, from which a galling fire had been maintained, were burnt. The besiegers having rung the church bells as an alarm, the Royalists had to beat a hasty retreat, but not until they had effected their purpose.

On 29 June the first piece of artillery was placed in position against the House, and six shots were fired from a culverin placed in the park. On the following morning fire was opened from a demi-culverin in the lane, which was silenced the same day by a shot from the House.[20]

In June a detachment of cavalry was detached from the siege to act as cavalry for Major-General Brown,[21] whose force would combine with Waller's and be defeated at the Battle of Cropredy Bridge on 29 June.

On 11 July Morley sent to the Marquess this demand: "My Lord, — To avoid the effusion of Christian blood, I have thought fit to send your Lordship this summons to demand Basing House to be delivered to me for the use of the King and Parliament. If this be refused, the ensuing inconvenience will rest upon yourself. I desire a speedy answer, and rest. My Lord, your humble servant, Heebeet Moeley".[20]

To which the Marquess returned this reply : "Sir, — It is a crooked demand, and shall receive its answer suitable. I keep the House in the right of my Sovereign, and will do it in despight of your forces. Your letter I will preserve as a testimony of your rebellion. Winchestee".[20]

The siege was then renewed with great vigour until the latter end of August, when the provisions of the garrison began to fail, and some of the men deserted, upon which the Marquess made an example of one, which seems to have had the effect of preventing, for some time at least, a repetition of the attempt.[20]

On 2 September Norton sent a summons to the Marquess:

My Lord, These are in the name and by the authority of the Parliament of England, the highest court of justice in this kingdom, to demand the House and Garrison of Basing to be delivered unto me, to be disposed of according to order of Parliament. And hereof I expect your answer by this drum, within one hour after the receipt hereof, in the mean time I rest; yours to serve you, Richard Norton.[22]

To which the Marquess at once sent answer:

Sir,—Whereas you demand the House and Garrison of Basing by a pretended authority of Parliament, I make this answer: That without the King there can be no Parliament, by His Majesty's commission I keep the place, and without his absolute command shall not deliver it to any pretenders whatever. I am, yours to serve you, Winchester.[23]

Again the siege was prosecuted with increased fury, shot and shell being poured daily into the House, and many of the defenders falling, while famine was at the same time reducing their strength and energy. Some time previously a messenger had been despatched to the King for succour, and a promise was received that assistance should arrive on 4 September, with a view to which arrangements were made to co-operate from the House, but it was not until 11 September 1644 that welcome intelligence was received by the garrison that the reliefs were marching towards them, and had already reached Aldermaston.[23]

Gage's relief

editThe Royalists decided to send a relief column under the command of Colonel Gage from Oxford to Basing House, which is a distance of about 40 miles (64 km). The column set off on the night of 9 September 1644. As a subterfuge Gage wore an orange sash (usually worn by Parliamentary officers) in the hope that if seen from a distance the column would be taken for a Parliamentary one and perhaps if challenged he could bluff his way through enemy lines.[24]

An express message was sent from Oxford to Sir William Ogle, instructing him to co-operate with Gage, by entering Basing Park at the rear of the Parliamentarian quarters between four and five o'clock on the morning of Wednesday, 11 September.[23]

Ogle contented himself by sending a messenger to meet Gage, to say that he dared not send his troops, as some of the enemy's horse lay between Winchester and Basing.[23]

With reference to Ogle's conduct in this matter, there is in existence an old song, entitled, "The Royal Feast" a loyal song of the prisoners in the Tower of London, written by Sir Francis Wortley, and sung at the Andover Buck Feast on 16 September 1674, in which occurs these words:

The first and chief a marquess is,

Long with the state did wrestle,

Had Oglo done as much as he

They'd spoyled Will Waller's Castle:

Ogle had wealth and title got.

So layd down his commission.

The noble marquess would not yield.

But scorned all base conditions.[25]

Gage, being thus left to his own resources, held a council of war, and at seven o'clock, after a desperate struggle, gained the summit of Cowdery's Down, and, notwithstanding the exhausted condition of his troops, cut his way through the lines of the beleaguering forces. In his efforts he was ably assisted by the garrison, who made a vigorous sally, and being thus attacked in front and rear, the Parliamentarians soon left the way clear, and Gage made a triumphant entry into the House, carrying with him a large quantity of ammunition. The attacking forces, being thrown into great disorder, retired to some distance to re-organize themselves, and the opportunity was seized by Gage to collect food and forage for the use of the garrison. The provisions being brought in, a sally was made by 100 musketeers under the command of Major Cufaude and Captain Hall, and the enemy's works upon the Basing side were carried, including the church, the garrison of which were made prisoners, and consisted of captains John Jephson and Jarvis, one lieutenant, two sergeants, and 30 soldiers. The quarters of the Roundheads were that night set alight in three places, "the enemy so hastening from these works as scarcely three could be made to stay the killing".[26]

The following day, 12 September, warrants were issued to the adjacent villages to supply certain quantities of food on the morrow, on pain of having their towns burnt in the event of non-fulfilment. This plan was merely a ruse on the part of Gage to mislead the besiegers as to his intentions, information having reached the House that large bodies of troops had arrived at the villages between Silchester and Kingsclere, with a view to cut off his retreat upon Oxford. At eleven o'clock that night Gage marched off with his men as silently as possible, and, while the Roundheads were peacefully sleeping, reached the River Kennet at Burghfield Bridge, and having forded the river (the bridge being destroyed) on the following morning crossed the Thames at Pangbourne, and arriving at Wallingford in safety, decided upon quartering there for the night. The next day he returned in triumph to Oxford, having completed the arduous task entrusted to him with a loss of only eleven men killed and forty or fifty wounded. For this exploit he received the honour of knighthood at the hands of the King on 1 November.[27]

Reinvestment

editOn the withdrawal of Gage, the House was quickly re-invested by the troops under Waller, Basing Church was re-taken, and the siege pushed with renewed energy.[27]

Between this period and November the time was spent by the garrison in arranging and carrying out a series of sallies, in many of which they succeeded in destroying some of the works of the enemy, at others seizing their provisions. With November came a complaint of shortness of food, as on the first of that month the stock of bread, corn, and beer was exhausted, while the officers had already denied themselves one meal a day. During the succeeding fortnight the garrison were in a sad condition, and appear to have lived from day to day upon what could be seized by the troops in their sallies.[28]

Gages's second relief

editNews of their condition having reached the King, Sir Henry Gage was again instructed to attempt the relief of Basing House.[29] The King, apparently with a view of diverting attention from Gage, marched towards Hungerford with his troops. Waller, wearied with twenty-four weeks of unsuccessful attempts upon the place with his army, reduced from 2,000 to 700, while disease was working havoc among the remainder, on hearing of the King's movements determined to retire into winter quarters.[29]

Accordingly, on 15 November, after burning their huts, the foot marched in the direction of Odiham, leaving the horse to cover their retreat. The garrison, though weakened by famine and want of rest, were determined to give their enemies a parting shot, and seized the opportunity. Cornet Bryan fell upon their retreating forces with a party of horse, and threw them into great disorder.[29]

On Tuesday, 19 November Gage proceeded to carry out his instructions, accompanied by 1,000 horse soldiers, each carrying on his saddle bow a sack of corn, and bearing around his waist a "skein of match", besides taking many cartloads of other necessaries. The next night Gage arrived with his troops opposite the House, intending to cut his way through the enemy's lines, and arranged that having arrived close to the House each trooper was to throw down the articles carried by him and at once make good his retreat. These plans were however not carried out when it was found that there was no enemy to contend with, and Gage rode into Basing House to the great joy of the defenders.[29]

The following winter and summer appear to have passed in comparative quiet the garrison being sufficiently occupied in repairing the damage caused by the enemy's artillery and in the accumulation of provisions against the arrival of another attacking party.[28]

Third siege

editMeanwhile, the King's cause became more and more hopeless. Fairfax had gained the important victory of Naseby, where Oliver Cromwell, who was in command of the horse, took part. Leicester, Bridgwater, Bath, Sherborne, and Bristol had surrendered in quick succession. Fairfax marched to the relief of Plymouth, then closely besieged by the King's troops. Cromwell had orders to keep the road to London open, by reducing those places which at that time obstructed it; and on 21 September 1645, he appeared before Devizes Castle, which surrendered on the following day.[30]

From his capture of Winchester and the surrender of its Castle on 5 October, Cromwell marched to Basing House, to which Colonel John Dalbier—an old German officer who had served under the Duke of Buckingham, and had been equally ready to drill the Parliamentary troops—had for some weeks been laying siege. Cromwell arrived on 8 October 1645,[31] bringing with him a siege-train of five demi-cannons (32-pounders) and a 63-pounder cannon.[32] It was through the possession of siege-guns that he hoped to win his way where so many of his predecessors in command had failed. On 11 October when he was ready to open fire, he summoned the garrison to surrender. The defenders of the noble mansion of the Catholic Marquess of Winchester, were not the professional soldiers to whom Cromwell was always ready to give honourable quarter. They had, so at least ran his accusation, been evil neighbours to the country people. Their house was "a nest of Romanists", who, of all men, could least make good their claim to wage war against the Parliament. If they refused quarter now, it would not be offered to them again.[31]

There were no signs of the garrison yielding. They treated Cromwell's summons lightly and miscalculated the power of his heavy guns. By the evening of 13 October two wide breaches had been effected, and at two in the morning it was resolved to storm the place at six, when the sky would be growing clear before the rising of the sun. The weary soldiers were directed to snatch a brief rest, but Cromwell spent part at least of the remainder of the night in meditation and prayer. He was verily persuaded that he was God's champion in the war against the strongholds of darkness, and as he figured to himself the idolaters and the idols behind the broken wall in front of him, the words, "They that make them are like unto them, so is every one that trusteth in them", rose instinctively to his lips.[31]

At the appointed hour the storming parties were let loose upon the doomed house, rising for the last time in its splendour over field and meadow. It had been said that the old house and the new were alike fit to make "an emperor's court". The defenders were all too few to make head against the surging tide of war.[31][d]

Quarter was neither asked nor given until the whole of the buildings were in the hands of the assailants. Women, as they saw their husbands, their fathers, or their brothers slaughtered before them, rushed forward to cling to the arms and bodies of the slayers. One, a maiden of no ordinary beauty, a daughter of Dr. Matthew Griffith, an Anglican clergyman, expelled from the City of London, hearing her father abused and maltreated (he was wounded but not mortally), gave back angry words to his reviler. The incensed soldier, maddened with the excitement of the hour, struck her on the head, killing her.[34] Six of the ten priests in the House were slain, and the four others held for the gallows.[31]

After a while the rage of the soldiers turned to thoughts of booty. Plate and jewels, stored gold and cunningly wrought tapestry fell prey to the victors. The men who were spared were stripped of their outer garments, and old Inigo Jones was carried out of the House wrapped in a blanket, because the spoilers had left him absolutely naked.[35]

One hundred rich petticoats and gowns which were discovered in the wardrobes were swept away amongst the common plunder, whilst the dresses were stripped from the backs of the ladies. On the whole, however, the women were, as a contemporary narrative expressed it, "coarsely but not uncivilly used". None of the women in the very heat of the soldiers' fury was raped, a common occurrence when fortified places were taken by storm, because Cromwell disapproved of such acts and forbade them on pain of death for the soldiers under his command.[35]

The booty is said to have been worth £200,000, and Hugh Peters, Cromwell's chaplain, in his "Full and last Relation of all things concerning Basing House," speaks of "a bead in one room furnished that cost £1,300". Peters himself presented to the Parliament in London the Marquess's own colours, which bore the motto of the King's coronation money, "Donee pax redeat terris" ("until peace return to the earth").[36]

In the midst of the riot, the House was discovered to be on fire. The flames spread rapidly, and of the stately pile there soon remained no more than the gaunt and blackened walls. Before it was too late the booty had been dragged out upon the sward, and the country people flocked in crowds to buy the cheese, the bacon, and the wheat which had been stored within. Prizes of greater value were reserved for more appreciative chapmen.

Contemporary reports of the number killed and taken prisoner vary. The historian S. R. Gardiner stated that the most probable estimate asserts that 300 were taken prisoner and 100 were slain, while G. N. Godwin, who wrote a detailed history of the siege, states that about 200 were taken prisoner and that 74 men and one woman (the daughter of Dr. Griffen) were seen to be dead, with more dying unseen because they were trapped in the fire.[37]

The Marquess himself owed his life to the courtesy with which he had formerly treated Colonel Hammond, who had been his prisoner for a few days. Hammond now in turn protected his former captor, though he could not prevent the soldiers from stripping the old man of his costly attire. After this the lord of the devastated mansion was safe from all but one form of insult. Consideration for fallen greatness never entered into the thoughts of a Puritan controversialist, even when that controversialist was of as kindly a disposition as was Hugh Peters. A Catholic, too, was beyond all bounds of religious courtesy, and Peters thought it well (as Cheynell had thought it well in the presence of the dying Chillingworth), to enter into argument with the fallen Marquess. Did he not now see, he asked him, the hopelessness of the cause which he had maintained? "If the King", was the proud reply, "had no more ground in England but Basing House, I would adventure as I did, and so maintain it to the uttermost. Basing House is called Loyalty". On the larger merits of the Royal cause he refused to enter. "I hope", he simply said, "that the King may have a day again".[38]

The feeling of the day about the slaughter among supporters of the Parliamentary cause is well brought out in a contemporary London newspaper. "The enemy, for aught I can learn, desired no quarter, and I believe that they had but little offered them. You must remember what they were: they were most of them Papists; therefore our muskets and our swords did show but little compassion, and this house being at length subdued, did satisfy for her treason and rebellion by the blood of the offenders".[38]

Cromwell's characteristic letter dated from Basingstoke on 14 October 1645, gives the most detailed surviving description of the disposition of the forces for the attack. It is addressed to William Lenthall, the Speaker of the House of Commons. Cromwell did not mention the killings after a summons to surrender had been rejected, because as the laws of war then stood, he did not see any need to give such an account: [e]

I thank God, I can give you a good account of Basing. After our batteries were placed, we settled the several posts for the storm: Colonel Dalbiere was to be on the north side of the House next the Grange, Colonel Pickering on his left hand, and Sir Hardress Waller's and Colonel Mountague's Regiments next to him. We stormed this morning after six of the clock; the signal for falling on was the firing four of our cannon, which being done, our men fell on with great resolution and cheerfulness; we took the two houses without any considerable loss to ourselves; Colonel Pickering stormed the new House, passed through and got the gate of the old House, whereupon they summoned a parley, which our men would not hear. In the mean time Colonel Mountague's and Sir Hardress Waller's Regiments assaulted the strongest work, where the enemy kept his court of guard, which with great resolution they recovered, beating the enemy from a whole culverin, and from that work, which having done, they drew their ladders after them and got over another work, and the House wall before they could enter. In this Sir Hardress Waller, performing his duty with honour and diligence, was shot on the arm, but not dangerously. We have had little loss, many of the enemy our men put to the sword and some officers of quality. Most of the rest we have prisoners, amongst which the Marquess and Sir Robert Peake, with divers other officers, whom I have ordered to be sent up to you. We have taken about ten pieces of ordnance, much ammunition, and our soldiers a good encouragement.[f]

Cromwell went on to recommend that what remained of the fortifications should be destroyed, and that a garrison should be established at Newbury to keep Donnington Castle in check.[38] Having given this advice he moved rapidly west to rejoin Fairfax at Crediton on the way he took the surrender of Lanford House on 17 October without the formality of a siege.[38]

Aftermath

editIt is a tradition that the Marquess had written with his own hand on the windows of the House, "Aymez Loyaute", which became the motto of his family.[36]

At the suggestion of Cromwell, the House, and works were, by a resolution of the House of Commons, dated 15 October 1645, (the day after the capture) ordered to be "totally slighted and demolished", and whosoever would fetch away any stone, brick or other materials was to have the same freely for his pains.[36]

Near neighbourhood

editThe near neighbourhood of Basing House involved the town of Basingstoke to some extent in the protracted military operations of which the former was for two years the centre. The condition of Basingstoke Church, the walls of which are indented with shot on every side, but especially on the south, makes it almost certain that (as is known to have been the case at Alton and at Basing itself) the sacred building afforded a refuge to the troops of one or other army, while their enemies assaulted it. A Parliamentary committee had its sittings in the town in July, 1644, but fled on the approach of Gage with his relief.[42]

Elias Archer in his True Relation of the Marchings of the Red Trained Bands of Westminster, the Green Auxiliaries of London, and the Yellow Auxiliaries of the Tower Hamlets (London 4to. 1643) mentions the repeated occupation of the town by the Royal troops, while the following extracts show the use to which it was put by their opponents during the first siege.[43]

Wednesday, 8 November 1643. The Trained Bands "withdrew all their forces to Basingstoke, where they stayed and refreshed their men about three or four days in respect of the extremity of hard service and cold weather, which their foot forces had undergone and endured before the house".[44]

On Monday, 13 November 1643, "in the morning, in regard of the bad success of the preceding day's service and the disheartening which our men sustained by it, together with the present foulness of the weather (for it was a very tempestuous morning of wind, rain and snow) all the forces were again withdrawn to Basingstoke, where we refreshed our men and dried our clothes".[44]

Notes

edit- ^ Colonel Harvey "a merchant whose military experience consisted of dispersing a crowd of London women who were petitioning parliament for peace".[4]

- ^ According to Agostini's despatch of 22 March/1 April, there were also plans for treacherous help in Reading and Oxford "anzi contro la stessa persona del lie", Gardiner states as this is not hinted at anywhere else, it is probably a mere rumour.[14]

- ^ Skellum Grenvile is the name by which he is now known in the Parliamentary newspapers, Skellum, Gardiner suppose, being equivalent to Schelm.[15]

- ^ In 1991 a severed head was unearthed in the course of an archaeological dig. The skull had an unhealed wound from a sword cut and the man was likely killed in the final attack on the house.[33]

- ^ Immediately before going to Basing House, Cromwell had used his siege-train to subdue the Royalist town of Winchester and its castle. His treatment of the Protestant garrison there, which when the situation became hopeless surrendered to him, and their surrender was accepted, was in marked contrast to his treatment of the garrison of Basing House, which did not surrender when offered a chance to do so and contained known Roman Catholics.

On the morning of 28 September, Cromwell entered Winchester without opposition. Almost his first act was to offer to Bishop Curl a convoy to conduct him to a place of safety. The bishop, however, preferred to take refuge in the castle. By 5 October Cromwell's batteries opened fire, and a practicable breach being soon effected, the governor gave up hope and surrendered. "You see," wrote Cromwell to the speaker, "God is not weary of doing you good. I confess, sir. His favour to you is as visible when He comes by His power upon the hearts of His enemies, making them quit places of strength to you, as when he gives courage to your soldiers to attempt hard things".[39] Cites: Cromwell to Lenthall, 6 October. Carlyle, Letter XXXII. Carlyle follows Rushworth in calling this a letter to Fairfax ; but see C.J. iv. 249, and Perfect Diurnal E. 264, 26.). In the cause of the doomed King all but the very staunchest slackened their effort, whilst the least vigorous of his enemies knew now that failure was impossible.

Cromwell was as prompt in the execution of discipline as he was in the attack upon a fortress. Six of his men were caught plundering the disarmed soldiers of the garrison as they marched out. He hanged one of them on the spot, and sent the others to Oxford, that the new governor, Sir Thomas Glemham, might deal with them as he pleased. Glemham, however, thanking Cromwell for his courtesy, set the rogues at liberty.[40] - ^ The date of Cromwell's Letter affords evidence of miscalculation in a curious horoscope, the original of which is in the Bodleian Library. It is said to have been drawn by William Lilly, the Astrologer, to solve the problem, "if Basing House would be taken", and assigns 16 September as the date of its capture.[41]

Citations

edit- ^ Hone 1838, p. 72.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 415.

- ^ a b Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 416–417.

- ^ Manganiello 2004, p. 46..

- ^ J. Jefferson, Sketch of the History of Holy Ghost Chapel, at Basingstoke in Hampshire, 2nd edition (J. Lucas, Basingstoke 1808), p. 19 (Google).

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 417.

- ^ Randall 2015, p. 84.

- ^ a b c Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 426.

- ^ Gardiner 1886, p. 239..

- ^ Gardiner 1886, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 417–418.

- ^ Gardiner 1886, p. 240..

- ^ Gardiner 1886, p. 240.

- ^ Gardiner 1886, p. 376.

- ^ a b c Gardiner 1886, p. 377.

- ^ a b Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 418.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 419.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 419–420.

- ^ a b c d Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 420.

- ^ Gardiner 1889, p. 360.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 420–421.

- ^ a b c d Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 421.

- ^ Young & Emberton 1978, p. 94.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 422.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 422–423.

- ^ a b Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 423.

- ^ a b Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 423–424.

- ^ a b c d Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 424.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 426–427.

- ^ a b c d e Gardiner 1889, p. 345.

- ^ Godwin 1904, p. 346.

- ^ Allen 1992, pp. 12–15.

- ^ Godwin 1904, p. 358.

- ^ a b Gardiner 1889, p. 346.

- ^ a b c Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 429.

- ^ Godwin 1906, pp. 354–355.

- ^ a b c d Gardiner 1889, p. 347.

- ^ Gardiner 1889, p. 343.

- ^ Gardiner 1889, p. 344.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 428.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 430.

- ^ Baigent & Millard 1889, pp. 430–431.

- ^ a b Baigent & Millard 1889, p. 431.

References

edit- Allen, David (1992). "A Civil War severed head". Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society Section Newsletter. 17: 14–15 – via Archaeology Data Service.

- Baigent, Francis Joseph; Millard, James Elwin (1889), A History of the Ancient Town and Manor of Basingstoke in the County of Southampton; with a Brief Account of the Siege of Basing House, A.D. 1643–1645, London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co.

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1886), History of the Great Civil War, 1642–1649, vol. 1, Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (1889), History of the Great Civil War, 1642–1649, vol. 2, Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Godwin, George Nelson (1906), "Basing House", in Jeans, G. E. (ed.), Memorials of Old Hampshire, London and Derby: Bemrose and Sons

- Godwin, George Nelson (1904), The Civil War in Hampshire (1642–45) and the Story of Basing House, Southampton: H. M. Gilbert and Son

- Hone, William (1838), The Year Book of Daily Recreation and Information: concerning remarkable men and manners, times and seasons ..., London: Thomas Tegg & Son

- Manganiello, Stephen C. (2004), The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 0-8108-5100-8

- Randall, Dale B. J. (13 January 2015), Winter Fruit: English Drama, 1642–1660, University Press of Kentucky, p. 84, ISBN 978-0-8131-5770-2

- Young, Peter; Emberton, Wilfrid (1978), Sieges of the Great Civil War, 1642–1646 (illustrated ed.), Bell & Hyman