Barnum's American Museum was a dime museum located at the corner of Broadway, Park Row, and Ann Street in what is now the Financial District of Manhattan, New York City, from 1841 to 1865. The museum was owned by famous showman P. T. Barnum, who purchased Scudder's American Museum in 1841. The museum offered both strange and educational attractions and performances.[1] Some were extremely reputable and historically or scientifically valuable, while others were less so.

| Barnum's American Museum | |

|---|---|

Barnum's American Museum in 1858 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Manhattan, New York City |

| Opened | 1841 |

| Closed | 1865 |

| Demolished | 1868 |

History

editIn 1841, Barnum acquired the building and natural history collection of Scudder's American Museum[2] for less than half of its appraised value with the financial support of Francis Olmsted, by quickly purchasing it the day after the soon to be buyers, the Peale Museum Company, failed to make their payment.[3] He converted the five-story exterior into an advertisement lit with limelight. The museum opened on January 1, 1842.[4]

Its attractions made it a combination zoo, museum, lecture hall, wax museum, theater and freak show, in what was, at the same time, a central site in the development of American popular culture. Barnum filled the American Museum with dioramas, panoramas, "cosmoramas", scientific instruments, modern appliances, a flea circus, a loom powered by a dog, the trunk of a tree under which Jesus' disciples supposedly sat, an oyster bar, a rifle range, waxworks, glass blowers, taxidermists, phrenologists, pretty baby contests, Ned the learned seal, the Fiji Mermaid (a mummified monkey's torso with a fish's tail), midgets, Chang and Eng the Siamese twins, a menagerie of exotic animals that included beluga whales in an aquarium, giants, Native Americans who performed traditional songs and dances, Grizzly Adams's trained bears and performances ranging from magicians, ventriloquists and blackface minstrels to adaptations of biblical tales and Uncle Tom's Cabin.[3][5][6][7][8]

At its peak, the museum was open fifteen hours a day and had as many as 15,000 visitors a day.[1] Some 38 million customers paid the 25 cents admission to visit the museum between 1841 and 1865. The total population of the United States in 1860 was under 32 million.

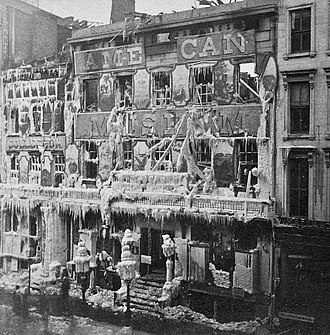

In November 1864, the Confederate Army of Manhattan attempted and failed to burn down the museum, but on July 13, 1865, the American Museum burned to the ground in one of the most spectacular fires New York has ever seen.[9] Animals at the museum were seen jumping from the burning building, only to be shot by police. Many of the animals unable to escape the blaze burned to death in their enclosures, including the two beluga whales who burned to death after the glass panes of their tank were broken in an attempt to quell the fire. [9]

It was allegedly during this fire that a fireman by the name of Johnny Denham killed an escaped tiger with his ax before rushing into the burning building and carrying out a 400-pound woman on his shoulders. Barnum's New Museum opened September 6, 1865, at 539-41 Broadway, between Spring and Prince Streets, but that also burned down, on March 3, 1868.[10] It was after this that Barnum moved on to politics and the circus industry.[11] Barnum's American Museum was one of the most popular attractions of its time.[12]

The site at Ann Street was then used for a new building for the New York Herald newspaper.[13]

In July 2000, a virtual museum version opened on the Internet, supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. It is hosted by CUNY and was maintained through 2015.[14]

Advertisement

editOne of the biggest attractions and advantages to the success of the American Museum was Barnum's advertising strategy. Barnum's self-professed goal was "to make the Museum the town wonder and talk of the town.[5]" To do this he was "not above exploiting his patrons' ignorance and credulity from time to time," as seen in some of his most well-known schemes: the Fiji mermaid, the Little Woolly horse, and the 'to the egress' signs.[6]

Barnum capitalized on the draw of some of his most famous attractions, often publishing articles in newspapers claiming that his exhibits were fake, which caused audiences to return to see them for themselves.[3] He printed off countless massive colored posters displaying the many exhibits within the museum. These posters often exaggerated the attractions they advertised, but this did not stop visitors from returning after finding out they had been misled. The poster for the Fejee mermaid was so massive that it covered a majority of the front of the museum.[3]

Attractions

editThe museum's collection included items collected throughout the world over a period of 25 years.[15] The museum offered many attractions which grew to great fame. One of the most famous was General Tom Thumb, a 35-inch tall dwarf who eventually garnered so much fame and success that Queen Victoria saw his performances twice, and Abraham Lincoln personally congratulated Thumb on his wedding.[16]: 84

Thumb wasn't the only physical oddity; there was also the Fiji Mermaid and Josephine Boisdechene, who had a large beard, which had grown to the length of two inches when she was only eight years old. As if to supplement Tom Thumb, the museum also had William Henry Johnson (Zip the Pinhead), who was one of Barnum's longest-running attractions. Barnum also exhibited giants such as Routh Goshen, who was known as the "Arabian Giant", and Anna Swan.[16]: 84 Another famous attraction was Chang and Eng, conjoined twins, who were extremely argumentative, both with each other and Barnum himself.

The museum also boasted an elegant theatre, called the "Lecture Room," and characterized in the popular Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion of 1853, "one of the most elegant and recherche halls of its class to be found anywhere," which would offer "every species of entertainment ... 'from grave to gay, from lively to severe,' ... [and] judiciously purged of every semblance of immorality."[17]

Impressively, these shows "[rivaled] or even [excelled] those of the neighboring theaters."[6] This was possible because: 1) these performances occurred in a space labeled a lecture hall, helping to distinguish them for those who would never have been near a theatre, and 2) "[Barnum] made the theatre into something it had rarely been before: a place of family entertainment, where men and women, adults and children, could intermingle safe in the knowledge that no indecencies would assault their senses either on stage or off."[3]

Barnum implemented several morality plays to be shown in his auditorium, many of which taught against the dangers of drinking. Werner points out the accessibility of these performances saying, "many persons who would not be seen in a theatre visited regularly the Museum Lecture Room—Barnum would never consent to calling it a theatre—where the moral dramas of 'Joseph and his Brethren,' 'Moses,' and 'The Drunkard' were performed."[7] These were especially popular with women, as alcoholism was becoming rampant among working-class men. These plays were often seen as the height of family-friendly entertainment, because they taught good lessons that were appropriate for all ages.

At one point, Barnum noticed that people were lingering too long at his exhibits. He posted signs indicating "This Way to the Egress". Not knowing that "Egress" was another word for "Exit", people followed the signs to what they assumed was a fascinating exhibit — and ended up outside.[18]

The five-story building also served great educational value. Aside from the different attractions, the museum also promoted educational ends, including natural history in its aquarium, menageries, and taxidermy exhibits; history in its paintings, wax figures, and memorabilia; and temperance reform and Shakespearean dramas in the "Lecture Room" or theater.[9] It was also the first museum to put human oddities on display as an organized freak show.[7] It was the American Museum that began the modern-day trend of exploiting the human body for the sake of mass entertainment.[3]

One of Barnum's most successful attractions was his large selection of living animals, which were a highlight for the visitors who had never seen exotic creatures. The animals in Barnum's "happy family" were poorly treated at best and neglected at worst.[3] Their standard of living is exemplified in the beluga whales he kept in a tank in the basement. The whales lived in a small 576 square foot tank, and when they frequently died, Barnum "promptly set about procuring additional specimens."[6]

See also

edit- Barnum Museum – completed in 1893 in Bridgeport, Connecticut

- Dime museum

- Sideshow

- St. Paul Building, later built on the museum's site

References

edit- ^ a b Kelley, Tina (July 1, 2000). "A Museum to Visit from an Armchair". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ Crockett, Zachary. "The Rise and Fall of Circus Freakshows". Priceonomics. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dennett, Andrea Stulman (1997). Weird and Wonderful : the Dime Museum in America. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814744215. OCLC 782877979.

- ^ Bailer, Darice (January 21, 2001). "The View From/Bridgeport; Museum Invites Visitors to Step Right Up". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Barnum, P.T. (1961). Browne, Waldo R. (ed.). Barnum's Own Story. New York: Dover Publications Inc.

- ^ a b c d Saxon, A.H. (1989). "P.T. Barnum and the American Museum". The Wilson Quarterly. Vol. 13. pp. 130–139.

- ^ a b c Werner, M. R. (1923). Barnum. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company Inc.

- ^ Chung, Jen (June 21, 2012). "Vintage Oddities: The Outlandish Attractions Of Barnum's American Museum". Gothamist. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Disastrous Fire" (PDF). The New York Times. July 14, 1865. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ Brown, T. Allston (1903). A History of the New York Stage. Vol. 2. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company. pp. 3–8.

- ^ Frank, Michael (June 21, 2002). "Will Wonders Never Cease?". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ "The Barnum's American Museum Illustrated". Barnum's American Museum Illustrated Magazine. 1850. Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ "Sunshine and shadow in New York. By Matthew Hale Smith. (Burleigh.) ." archive.org. 1869. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ "The Lost Museum". lostmuseum.cuny.edu. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Dyer, Brainerd (July 13, 1958). "Today in History". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 15, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Nickell, Joe (2005). Secrets of the sideshows. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-7179-2. OCLC 65377460.

- ^ "American Museum, New York". Gleason's Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion. Vol. IV, no. 5. January 29, 1853. p. 73. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Barnum, Phineas Taylor (April 1871). Struggles and Triumphs: Or, Forty Years' Recollections of P. T. Barnum. New York: American News Company. p. 140. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

External links

edit- "The Lost Museum". CUNY. American Social History Project (ASHP). 2015 [2002].

- Showman's Shorts— P.T. Barnum's American Museum (2021) on YouTube