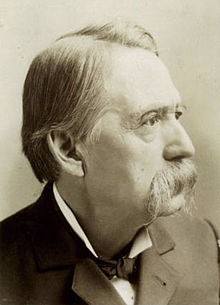

Thomas Dunn English (June 29, 1819 – April 1, 1902) was an American Democratic Party politician from New Jersey who represented the state's 6th congressional district in the House of Representatives from 1891 to 1895. He was also a published author and songwriter, who had a bitter feud with Edgar Allan Poe. Along with Waitman T. Barbe and Danske Dandridge, English was considered a major West Virginia poet of the mid 19th century.[1]

Thomas Dunn English | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Jersey's 6th district | |

| In office March 4, 1891 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | Herman Lehlbach |

| Succeeded by | Richard W. Parker |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 29, 1819 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | April 1, 1902 (aged 82) Newark, New Jersey, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

Biography

editEnglish was born in Philadelphia on June 29, 1819.[2] He attended the Friends Academy in Burlington, New Jersey, and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in 1839. His graduation thesis was on phrenology.[3] He studied law, and was admitted to the Philadelphia bar in 1842. He was a founding member of the American Numismatic Society in 1858.[4] By then, his career as a journalist and writer was already well underway.

Literary pursuits

editEnglish wrote scores of poems and plays as well as stories and novels, but his reputation as a writer was built on the ballad "Ben Bolt" (1843).[5] Written for Nathaniel Parker Willis's New-York Mirror, it was turned into a song and became very popular, with a ship, steamboat and racehorse soon named in its honor.[6] American opera singer Eleonora de Cisneros recorded this on an Edison Blue Amberol cylinder in 1912.[7][8]

Other works include the temperance novel Walter Woolfe, or the Doom of the Drinker in 1842 and the political romance MDCCCXLII. or the Power of the S. F. in 1846.[9] He was the founding editor of the monthly The Aristidean in New York,[10] which printed its first issue in February 1845.[11] English later edited several other journals, including the humorous magazine The John Donkey, American Review: A Whig Journal and Sartain's Magazine.[9]

English was a friend of author Edgar Allan Poe, but the two fell out amidst a public scandal involving Poe and the writers Frances Sargent Osgood and Elizabeth F. Ellet. After suggestions that her letters to Poe contained indiscreet material, Ellet asked her brother to demand the return of the letters. Poe, who claimed he had already returned the letters, asked English for a pistol to defend himself from Ellet's infuriated brother.[12] English was skeptical of Poe's story and suggested that he end the scandal by retracting the "unfounded charges" against Ellet.[13] The angry Poe pushed English into a fistfight, during which his face was cut by English's ring.[14] Poe later claimed to have given English "a flogging which he will remember to the day of his death", though English denied it; either way, the fight ended their friendship and stoked further gossip about the scandal.[14]

Later that year, Poe harshly criticized English's work as part of his "Literati of New York" series published in Godey's Lady's Book, referring to him as "a man without the commonest school education busying himself in attempts to instruct mankind in topics of literature".[15] The two had several confrontations, usually centered around literary caricatures of one another. One of English's letters which was published in the July 23, 1846, issue of the New York Mirror[16] caused Poe to successfully sue the editors of the Mirror for libel.[17] Poe was awarded $225.06 as well as an additional $101.42 in court costs.[18] That year English published a novel called 1844, or, The Power of the S.F. Its plot made references to secret societies, and ultimately was about revenge. It included a character named Marmaduke Hammerhead, the famous author of The Black Crow, who uses phrases like "Nevermore" and "lost Lenore." The clear parody of Poe was portrayed as a drunkard, liar, and domestic abuser. Poe's story "The Cask of Amontillado" was written as a response, using very specific references to English's novel.[19] Another Poe revenge tale, "Hop-Frog", may also reference English.[20] Years later, in 1870, when English edited the magazine The Old Guard, founded by the Poe-defender Charles Chauncey Burr, he found occasion to publish both an anti-Poe article (June 1870) and an article defending Poe's greatest detractor Rufus Wilmot Griswold (October 1870).[21]

Political career

editEnglish's first foray into politics was as an advocate of the annexation of Texas.[22] He moved to present-day Logan, West Virginia, in 1852, to New York City in 1857, and to Newark, New Jersey, a year later. He was a member of the New Jersey General Assembly in 1863 and 1864.[23]

English was elected as a Democrat to the Fifty-second and Fifty-third Congresses, serving in office from March 4, 1891, to March 3, 1895. He was chairman of the Committee on Alcoholic Liquor Traffic (Fifty-third Congress). He was an unsuccessful candidate for reelection in 1894 to the Fifty-fourth Congress.[23]

Later life and death

editAfter leaving Congress, English resumed his former literary pursuits in Newark. In 1896, he published Reminisces of Poe, in which he hinted at scandals without specificity. He did, however, defend Poe against rumors of drug use: "Had Poe the opium habit when I knew him (before 1846) I should both as a physician and a man of observation, have discovered it during his frequent visits to my rooms, my visits at his house, and our meetings elsewhere – I saw no signs of it and believe the charge to be a baseless slander".[24]

English died April 1, 1902, and was interred in Fairmount Cemetery in Newark.[23] His monument notes him as "Author of Ben Bolt".

Selected list of works

edit- Zephaniah Doolittle (1838) (as Montmorency Sneerlip Snags Esq.)[25]

- Walter Woolfe, or the Doom of the Drinker (1842)

- Ben Bolt (1843)

- MDCCCXLII. or the Power of the S. F. (1846)

- Gasology: A Satire (1877)

- Reminiscences of Poe (1896)

References

edit- ^ Rice, Otis (12 September 2010). West Virginia: A History. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-0-8131-2733-0.

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982: 203. ISBN 0-19-503186-5

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998: 349. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ^ L.H.L. (January 1909). "Obituary: Asher D. Atkinson". American Journal of Numismatics. 43 (3): 139. JSTOR 43587999.

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 293.

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 294.

- ^ Edison Blue Amberol cylinder recording of Ben Bolt (1912) on YouTube

- ^ Eleonora de Cisneros Oh! Don't you remember at Internet Archive

- ^ a b Griswold, Rufus Wilmot (ed). The Poets and Poetry of America. Philadelphia: Parry and McMillan, 1855: 576.

- ^ Moss, Sidney P. Poe's Literary Battles: The Critic in the Context of His Literary Milieu. Southern Illinois University Press, 1969: 176.

- ^ Thomas, Dwight and David K. Jackson. The Poe Log: A Documentary Life of Edgar Allan Poe 1809–1849. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987: 501. ISBN 0-8161-8734-7.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992: 191.

- ^ Moss, Sidney P. Poe's Literary Battles: The Critic in the Context of His Literary Milieu. Southern Illinois University Press, 1969: 220.

- ^ a b Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991: 291. ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 296.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. Checkmark Books, 2001: 81, 83, 91.

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991: 312–313. ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. Harper Perennial, 1991: 328. ISBN 0-06-092331-8

- ^ Rust, Richard D. "Punish with Impunity: Poe, Thomas Dunn English and 'The Cask of Amontillado'" in The Edgar Allan Poe Review, Vol. II, Issue 2 – Fall, 2001, St. Joseph's University

- ^ Benton, Richard P. "Friends and Enemies: Women in the Life of Edgar Allan Poe" as collected in Myths and Reality: The Mysterious Mr. Poe. Baltimore: Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1987: 16.

- ^ Hubbell, Jay B. (1954). "Charles Chauncey Burr: Friend of Poe". PMLA. 69 (4): 833–40. doi:10.2307/459933. JSTOR 459933.

- ^ Oberholtzer, Ellis Paxson. The Literary History of Philadelphia. Philadelphia: George W. Jacobs & Co., 1906: 297. ISBN 1-932109-45-5

- ^ a b c Thomas Dunn English profile, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Accessed August 13, 2007.

- ^ Quinn, Arthur Hobson. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998: 351. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ^ Gentleman's Magazine. William Evans Burton (editor). Chas. Alexander. 1838. pp. 187 ff.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

External links

edit- United States Congress. "Thomas Dunn English (id: E000188)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by or about Thomas Dunn English at the Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Dunn English at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Bibliography of Thomas Dunn English at Poetry-Archive.com

- Thomas Dunn English obituary from The New York Times