Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk[a] (7 March 1850 – 14 September 1937) was a Czechoslovak statesman, progressive political activist and philosopher who served as the first president of Czechoslovakia from 1918 to 1935. He is regarded as the founding father of Czechoslovakia.

Tomáš Masaryk | |

|---|---|

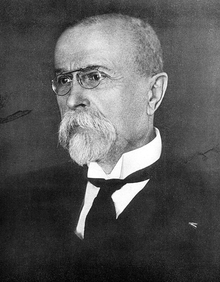

Masaryk in 1925 | |

| President of Czechoslovakia | |

| In office 14 November 1918 – 14 December 1935 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Edvard Beneš |

| Member of the House of Deputies | |

| In office 17 June 1907 – 25 September 1917 | |

| Constituency | Moravia |

| In office 9 April 1891 – 25 September 1893 | |

| Constituency | Bohemia |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Tomáš Masaryk 7 March 1850 Hodonín, Moravia, Austrian Empire |

| Died | 14 September 1937 (aged 87) Lány, Czechoslovakia |

| Political party |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5, including Alice, Herbert, Jan and Olga |

| Alma mater | University of Vienna (PhD, 1876; Dr. habil., 1879) |

| Profession | Philosopher |

| Signature | |

Born in Hodonín, Moravia (then part of the Austrian Empire), Masaryk obtained a doctorate at the University of Vienna and was a professor of philosophy at the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University. He began his political career as a deputy of the Austrian Reichsrat, serving from 1891 to 1893 and from 1907 to 1914. He was an advocate of restructuring the Austro-Hungarian Empire into a federal state, but by the outbreak of the First World War, he had become a supporter of Czech and Slovak independence. He went into exile, and travelled around Europe to organise and promote the Czechoslovak cause. He played a pivotal role in the establishment of the Czechoslovak Legion, which fought against the Central Powers during the war. In 1918, Masaryk, along with his protégés Edvard Beneš and Milan Rastislav Štefánik, travelled to the United States to obtain support from President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of State Robert Lansing. Their negotiations resulted in the Washington Declaration, which proclaimed the independence of a Czechoslovak state.

With the fall of Austria-Hungary in late 1918, the First Czechoslovak Republic received recognition from the Allied powers and Masaryk was recognised as head of its provisional government. He was formally elected president in November, and was reelected three times subsequently. Masaryk presided over a period of stability as Czechoslovakia emerged as a strong democratic state. He resigned from office in 1935 due to old age, and was succeeded by Beneš. He retired to the village of Lány and died two years later at the age of 87.

Early life

editMasaryk was born to a poor, working-class family in the predominantly Catholic city of Hodonín, Margraviate of Moravia, in Moravian Slovakia (in the present-day Czech Republic, then part of the Austrian Empire). The nearby Slovak village of Kopčany, the home of his father Jozef, also claims to be his birthplace.[1] Masaryk grew up in the village of Čejkovice, in South Moravia, before moving to Brno to study.[2]

His father, Jozef Masárik, was Slovak, born in Kopčany, Slovakia. Jozef Masárik was a carter and, later, the steward and coachman at the imperial estate in the nearby town of Hodonín. Tomáš's mother, Teresie Masaryková (née Kropáčková), was a Moravian of Slavic origin who received a German education. A cook at the estate, she met Masárik and they married on 15 August 1849.

Education

editAfter grammar school in Brno and Vienna from 1865[3] to 1872, Masaryk attended the University of Vienna and was a student of Franz Brentano.[4] He received his Ph.D. from the university in 1876 and completed his habilitation thesis, Der Selbstmord als soziale Massenerscheinung der modernen Civilisation (Suicide as a Social Mass Phenomenon of Modern Civilization), there in 1879.[4] From 1876 to 1879, Masaryk studied in Leipzig with Wilhelm Wundt and Edmund Husserl.[5] He married Charlotte Garrigue, whom he had met while a student in Leipzig, on 15 March 1878. They lived in Vienna until 1881, when they moved to Prague.

Masaryk was appointed professor of philosophy at the Czech Charles-Ferdinand University, the Czech-language part of Charles University, in 1882. He founded Athenaeum, a magazine devoted to Czech culture and science, the following year.[6] Athenaeum, edited by Jan Otto, was first published on 15 October 1883.

Masaryk's students included Edward Benes and Emanuel Chalupny.[7]

Masaryk challenged the validity of the epic poems Rukopisy královedvorský a zelenohorský, supposedly dating to the early Middle Ages and presenting a false, nationalistic Czech chauvinism to which he was strongly opposed. He also contested the Jewish blood libel during the 1899 Hilsner trial.[8]

Masaryk was greatly influenced by the 19th-century cult of science.[9] The 19th century was an age of tremendous scientific and technological advances, and as such scientists enjoyed immense prestige. Masaryk believed that social problems and political conflicts were the results of ignorance, and that provided that one undertook a proper "scientific" approach to studying the underlying causes it would be possible to devise the correct solutions.[9] As such, Masaryk saw his role as an educator who would enlighten the public from its ignorance and apathy.[9]

Politician

editMasaryk served in the Reichsrat from 1891 to 1893 with the Young Czech Party and from 1907 to 1914 in the Czech Progressive Party, which he had founded in 1900. At that time, he was not yet campaigning for Czech and Slovak independence from Austria-Hungary. Masaryk helped Hinko Hinković defend the Croat-Serb Coalition during their 1909 Vienna political trial; its members were sentenced to a total of over 150 years in prison, with a number of death sentences.

When the World War I broke out in 1914, Masaryk concluded that the best course was to seek independence for Czechs and Slovaks from Austria-Hungary. He went into exile in December 1914 with his daughter, Olga, staying in several places in Western Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States and Japan. Masaryk began organizing Czechs and Slovaks outside Austria-Hungary during his exile, establishing contacts which would be crucial to Czechoslovak independence. He delivered lectures and wrote several articles and memoranda supporting the Czechoslovak cause. Masaryk was pivotal in establishing the Czechoslovak Legion in Russia as an effective fighting force on the Allied side during World War I, when he held a Serbian passport.[10] In 1915 he was one of the first staff members of the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (now part of University College London), where the student society and senior common room are named after him. Masaryk became professor of Slavic Research at King's College London, lecturing on the problem of small nations. Supported by Norman Hapgood T. G. Masaryk wrote the first memorandum to president Wilson, concerning to independence of the Czechoslovak state, here in January 1917.[11]

During World War I and afterwards, Masaryk supported the unification of Kingdom of Serbia and Kingdom of Montenegro.[12]

Masaryk championed feminist causes, being influenced by his wife Charlotte Garrigue.[13] Masaryk's progressive ideas strongly influenced Washington Declaration of Czechoslovak Independence.

Czechoslovak Legion and US visit

editOn 5 August 1914, the Russian High Command authorized the formation of a battalion recruited from Czechs and Slovaks in Russia. The unit went to the front in October 1914 and was attached to the Russian Third Army.

From its start, Masaryk wanted to develop the legion from a battalion to a formidable military formation. To do so, however, he realized that he would need to recruit Czech and Slovak prisoners of war (POWs) in Russian camps. In late 1914, Russian military authorities permitted the legion to enlist Czech and Slovak POWs from the Austro-Hungarian army; the order was rescinded in a few weeks, however, because of opposition from other areas of the Russian government. Despite continuing efforts to persuade the Russian authorities to change their minds, the Czechs and Slovaks were officially barred from recruiting POWs until the summer of 1917.[citation needed] Under these conditions, the Czechoslovak armed unit in Russia grew slowly from 1914 to 1917. Masaryk preferred to concentrate on elites rather than public opinion.[14] On 19 October 1915, Masaryk gave the inaugural address at the newly opened School of Slavonic Studies at King's College London on "The Problem of Small Nations in the European Crisis", arguing that on both moral and practical grounds that the United Kingdom should support the independence efforts of "small" nations such as the Czechs.[14] Shortly afterwards, Masaryk crossed the English Channel to go to Paris, where he delivered a speech in French at the Institut d'études slaves of the Sorbonne on "Les Slaves parmi les nations" ("The Slavs Among the Nations"), receiving what was described as a "vigorous applause".[14]

During the war, Masaryk's intelligence network of Czech revolutionaries provided critical intelligence to the allies. His European network worked with an American counterespionage network of nearly 80 members, headed by Emanuel Viktor Voska (including G. W. Williams). Voska and his network, who (as Habsburg subjects) were presumed to be German supporters, spied on German and Austrian diplomats. Among other achievements, the intelligence from these networks was critical in uncovering the Hindu–German Conspiracy in San Francisco.[15][16][17][18] Masaryk began teaching at London University in October 1915. He published "Racial Problems in Hungary", with ideas about Czechoslovak independence. In 1916, Masaryk went to France to convince the French government of the necessity of dismantling Austria-Hungary. He consulted with his friend professor Pavel Miliukov, a leading Russian historian and one of the leaders of the Kadet Party, to introduce him to various members of Russian high society.[14]

In early 1916, the Czechs and Slovaks in Russian service were reorganized as the First Czecho-Slovak Rifle Regiment.[citation needed] In a rare attempt to influence public opinion, Masaryk opened up an office on Piccadilly Circus in London whose exterior was covered with pro-Czechoslovak slogans and maps with the intention of attracting the interest of those walking by.[14] One of Masaryk's most important British friends was the journalist Wickham Steed who wrote articles in the newspapers urging British support for Czechoslovakia.[19] Another important British contract for Masaryk was the historian Robert Seton-Watson, who also wrote widely in the British press urging British support for the "submerged" nations of the Austrian empire.[20] After the 1917 February Revolution he proceeded to Russia to help organize the Czechoslovak Legion, a group dedicated to Slavic resistance to the Austrians. Miliukov became the new Russian foreign minister in the Provisional government, and proved very sympathetic towards the idea of creating Czechoslovakia. After the Czechoslovak troops' performance in July 1917 at the Battle of Zborov (when they overran Austrian trenches), the Russian provisional government granted Masaryk and the Czechoslovak National Council permission to recruit and mobilize Czech and Slovak volunteers from the POW camps. Later that summer a fourth regiment was added to the brigade, which was renamed the First Division of the Czechoslovak Corps in Russia (Československý sbor na Rusi, also known as the Czechoslovak Legion – Československá legie). A second division of four regiments was added to the legion in October 1917, raising its strength to about 40,000 by 1918.

Masaryk formed a good connection with Russian supreme commanders, Mikhail Alekseyev, Aleksei Brusilov, Nikolay Dukhonin and Mikhail Diterikhs, in Mogilev, from May 1917.

Masaryk travelled to the United States in 1918, where he convinced President Woodrow Wilson of the righteousness of his cause. On 5 May 1918, over 150,000 Chicagoans filled the streets to welcome him; Chicago was the centre of Czechoslovak immigration to the United States, and the city's reception echoed his earlier visits to the city and his visiting professorship at the University of Chicago in 1902 (Masaryk had lectured at the university in 1902 and 1907). He also had strong links to the United States, with his marriage to an American citizen and his friendship with Chicago industrialist Charles R. Crane, who had Masaryk invited to the University of Chicago and introduced to the highest political circles (including Wilson). Except for president Wilson and the secretary of the state Robert Lansing this was Ray Stannard Baker, W. Phillips, Polk, Long, Lane, D. F. Houston, William Wiseman, Harry Pratt Judson and the French ambassador Jean Jules Jusserand. And Bernard Baruch, Vance McCormick, Edward N. Hurley, Samuel M. Vauclain, Colonel House too. At the Chicago meeting on 8 October 1918, Chicago industrialist Samuel Insull introduced him as the president of the future Czechoslovak Republic de facto and mentioned his legions.[21] On 18 October 1918 he submitted to president Thomas Woodrow Wilson "Washington Declaration" (Czechoslovak declaration of independence) created with the help of Masaryk American friends (Louis Brandeis, Ira Bennett, Gutzon Borglum, Franklin K. Lane, Edward House, Herbert Adolphus Miller, Charles W. Nichols, Robert M. Calfee, Frank E. J. Warrick, George W. Stearn and Czech Jaroslav Císař) as the basic document for the foundation of a new independent Czechoslovak state. Speaking on 26 October 1918 as head of the Mid-European Union in Philadelphia, Masaryk called for the independence of Czechoslovaks and the other oppressed peoples of central Europe.

T.G. Masaryk's heroic defence of the Jewish defendant in the Hilsner Trial left a lasting mark on him and led to a deep interest in Jewish thought, Zionism and interreligious relations.[22] At the same time, according to Czech historian Jan Láníček, Masaryk believed that Jews had a "great influence on newspapers in all the Allied countries", and helped the nascent state of Czechoslovakia during its struggle for independence.[23]

Leader of Czechoslovakia

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2012) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

With the fall of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918, the Allies recognized Masaryk as head of the provisional Czechoslovak government. On 14 November of that year, he was elected president of Czechoslovakia by the National Assembly in Prague while he was in New York. On 22 December, Masaryk publicly denounced the Germans in Czechoslovakia as settlers and colonists.[24]

Masaryk was re-elected three times: in May 1920, 1927, and 1934. Normally, a president was limited to two consecutive terms by the 1920 constitution, but a one-time provision allowed the first president–Masaryk–to run for an unlimited number of terms.

On paper, Masaryk had a somewhat limited role; the framers of the constitution intended to create a parliamentary system in which the prime minister and cabinet held actual power. However, a complex system of proportional representation made it all but impossible for one party to win a majority. Usually, ten or more parties received the 2.6 per cent of votes needed for seats in the National Assembly. With so many parties represented, no party even approached the 151 seats needed for a majority; indeed, no party ever won more than 25 per cent of the vote. These factors resulted in frequent changes of government; Masaryk's tenure saw ten cabinets headed by nine statesmen. Under the circumstances, Masaryk's presence gave Czechoslovakia a large measure of stability. This stability, combined with his domestic and international prestige, gave Masaryk's presidency more power and influence than the framers of the constitution intended.

He used his authority in Czechoslovakia to create the Hrad (the Castle), an extensive, informal political network. Under Masaryk's watch, Czechoslovakia became the strongest democracy in Central Europe. Masaryk's status as a Protestant leading a mainly Catholic nation led to criticism, as did his promotion of the 15th-century proto-Protestant Jan Hus as a symbol of Czech nationalism.[25]

There were founded "The Masaryk Academy of Labour", for the scientific study of scientific management too, with the Masaryk's supporting in Prague in 1918 and Masaryk University in Brno.[26]

Masaryk visited France, Belgium, England, Egypt and the Mandate for Palestine in 1923 and 1927. With Herbert Hoover, he sponsored the first Prague International Management Congress, a July 1924 gathering of 120 global labour experts (of which 60 were from the United States), organized with Masaryk Academy of Labour.[27] After the rise of Adolf Hitler, Masaryk was one of the first political figures in Europe to voice concern.

Masaryk resigned from office on 14 December 1935, because of old age and poor health, and was succeeded by Edvard Beneš.

Death and legacy

editMasaryk (b. 07 March 1850) died less than two years after leaving office, at the age of 87, in Lány on 14 September 1937. He was buried next to his wife in a plot at Lány cemetery, where later the remains of Jan Masaryk and Alice Masaryková were laid to rest.

Masaryk did not live to see the Munich Agreement or the Nazi occupation of his country, and was known as the Grand (Great) Old Man of Europe.

Commemorations

editAs the founding father of Czechoslovakia, Masaryk is revered by Czechs and Slovaks.

Masaryk University in Brno, founded in 1919 as Czechoslovakia's second university, was named after him when it was founded; after 30 years as Univerzita Jana Evangelisty Purkyně v Brně, it was renamed for Masaryk in 1990.

Commemorations of Masaryk have been held annually in the Lány cemetery on his birthday and day of death (7 March and 14 September) since 1989.

The Czechoslovak, then Czech Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, established in 1990, is an honour awarded to individuals who have made outstanding contributions to humanity, democracy and human rights.

He is commemorated by a number of statues, busts, plaques, coins and postage stamps. Although most are in or of the Czech Republic and Slovakia, Masaryk has a statue on Embassy Row in Washington, D.C., and in the Midway Plaisance park in Chicago and is memorialized in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park rose garden.[28] A plaque with a portrait of Masaryk is on the wall of a hotel in Rakhiv, Ukraine, where he reportedly resided from 1917 to 1918, and a bust was erected in 2002 on Zakhysnykiv Ukrainy Square (former Druzhby Narodiv Square) in Uzhhorod, Ukraine.

Avenida Presidente Masaryk (President Masaryk Avenue) is a main thoroughfare in the exclusive Polanco neighbourhood of Mexico City. In 1999 the city of Prague donated a statue[29] of Masaryk to Mexico City, one of the two originals made when the statue for the Prague Castle was being prepared for the 150th anniversary of his birth.[30]

The community of Masaryktown, Florida, founded by Slovaks and Czechs, is named after him.[31]

In Israel, Masaryk is considered an important figure and a national friend. A village was named after him - Kibbutz Kfar Masaryk near Haifa, which was largely founded by Jewish immigrants from Czechoslovakia. One of the main squares in Tel Aviv is Masaryk Square (he had visited the city in 1927). In Haifa, one of the junctions in the city was named after him as well. Many cities in Israel named streets after his name, including Jerusalem, Petach Tikva, Netanya, Nahariya and others.[32] A Masaryk forest was planted in the Western Galilee.[33]

Streets in Zagreb, Belgrade, Dubrovnik, Daruvar, Varaždin, Novi Sad, Smederevo and Split are named Masarykova ulica, and a main thoroughfare in Ljubljana is named after Masaryk. Streets named Thomas Masaryk can be found in Geneva[34] and Bucharest.[citation needed]

Asteroid 1841 Masaryk, discovered by Luboš Kohoutek, is named after him.[35]

Honours and awards

editHe received awards and decorations before and after World War I.[36][37]

National honours

edit- Austria-Hungary: Jubilee Military Medal (1898)

- Austria-Hungary: Military Jubilee Cross (1908)

- Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovak War Cross 1918 (1919)

- Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovak Revolutionary Medal (1919)

- Czechoslovakia: Order of the Falcon (1919)

- Czechoslovakia: Czechoslovak Victory Medal (1922)

Foreign honours

edit- Kingdom of Yugoslavia: Order of Karađorđe's Star (1920)

- France: Légion d'honneur (1921)

- Kingdom of Italy: Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (1921)

- Tunisia: Order of Glory (1923)

- United Kingdom: Order of St Michael and St George (1923)

- Belgium: Order of Leopold (1923)

- Spain: Order of Charles III (1924)

- Denmark: Order of the Elephant (1925)

- Poland: Order of the White Eagle (1925)

- Austria: Decoration of Honour for Services to the Republic of Austria (1926)

- Kingdom of Romania: Order of Carol I (1927)

- Kingdom of Romania: Commemorative Cross of the 1916–1918 War (1927)

- Greece: Order of the Redeemer (1927)

- Latvia: Order of the Three Stars (1927)

- Empire of Japan: Order of the Chrysanthemum (1928)

- Kingdom of Egypt: Order of Muhammad Ali (1928)

- Netherlands: Order of the Netherlands Lion (1929)

- Holy See: Order of the Holy Sepulchre (1929)

- Lithuania: Order of the Cross of Vytis (1930)

- Finland: Order of the White Rose of Finland (1930)

- Portugal: Military Order of Saint James of the Sword (1930)

- Estonia: Order of the Cross of the Eagle (1931)

- Spanish Republic: Order of the Spanish Republic (1935)

- Siam: Order of the White Elephant (1935)

- Colombia: Order of Boyacá (1937)

Philosophy

editMasaryk's motto was "Fear not, and steal not" (Czech: Nebát se a nekrást). A philosopher and an outspoken rationalist and humanist, he emphasised practical ethics reflecting the influence of Anglo-Saxon philosophers, French philosophy and—in particular—the work of 18th-century German philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, who is considered the founder of nationalism. Masaryk was critical of German idealism and Marxism.[38]

Books

editHe wrote several books in Czech, including The Czech Question (1895), The Problems of Small Nations in the European Crisis (1915), The New Europe (1917), and The World Revolution (Svĕtová revoluce; 1925) translated into English as The Making of a State (1927). Karel Čapek wrote a series of articles, Hovory s T.G.M. ("Conversations with T.G.M."), which were later collected as Masaryk's autobiography.

Personal life

editMasaryk married Charlotte Garrigue in 1878, and took her family name as his middle name. They met in Leipzig, Germany, and became engaged in 1877. Garrigue was born in Brooklyn to a Protestant family with French Huguenots among their ancestors. She became fluent in Czech and published articles in a Czech magazine.[39] Hardships during the World War I took their toll, and she died in 1923. Their son, Jan, was a Czechoslovak ambassador in London, foreign minister in the Czechoslovak government-in-exile (1940–1945) and in the governments from 1945 to 1948. They had four other children: Herbert, Alice, Eleanor, and Olga.

Born and raised a Catholic, Masaryk later became a Protestant; first joining the Reformed Church in Austria and later the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren in 1918 upon Czechoslovak independence, but he was mostly non-practising and rarely attended religious services.[40] His conversion was influenced by the 1870 declaration of papal infallibility and by his wife Charlotte, who was raised as a Unitarian.[41]

Family tree

edit| Tomáš Masaryk | Charlotte Garrigue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alice | Herbert | Jan | Eleanor | Olga | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bibliography

edit- (1885) Základové konkretné logiky (Foundations of Concrete logic). Prague. (German: Versuch einer concreten Logik), Vienna, 1887).

- (1898) Otázka sociální (The Social Question). Prague. (German: Die philosophischen und sociologischen Grundlagen des Marxismus), Vienna, 1899).

- (1913) Russland und Europa (Russia and Europe). Jena, Germany. (The Spirit of Russia, tr. Eden and Cedar Paul, London, 1919).

- (1918) The New Europe, London.

- (1919) The Spirit of Russia: Studies in History, Literature and Philosophy, trans. by Paul, Eden and Cedar, 2 vols. (London: Allen & Unwin, 1919) [2] Vol. 1, [3] Vol. 2.

- (1922) The Slavs After the War, London.

- (1925) Světová revoluce (World revolution). Prague. (The Making of a State, tr. H. W. Steed, London, 1927; Making of a State, tr. Howard Fertig, 1970.)

See also

edit- School of Brentano, a group of philosophers and psychologists who studied with Franz Brentano

- 1841 Masaryk, an asteroid

References

edit- ^ Czech: [ˈtomaːʒ ˈɡarɪk ˈmasarɪk]

- ^ Michaláč, Jozef 2007 T.G. Masaryk a kopčianska legenda. Kde sa v skutočnosti narodil náš prvý prezident? Bratislava: Nestor.

- ^ Čapek, Karel. 1995 [1935–1938]. Talks with T.G. Masaryk, tr. Michael Henry Heim. North Haven, CT: Catbird Press, p. 77.

- ^ Brno, Studium na gymnáziu, návštěvy města (in Czech), Masarykův ústav a Archiv AV ČR, retrieved 2 March 2019

- ^ a b Zumr, Joseph. 1998. "Masaryk, Tomáš Garrigue (1850–1937)". pp. 165–66 in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ed. Edward Craig. London: Routledge.

- ^ Čapek, Karel. 1995 [1935–1938]. Talks with T.G. Masaryk, tr. Michael Henry Heim. North Haven, CT: Catbird Press, p. 33

- ^ Lepka, Karel (2015). Mathematics in T. G. Masaryk journal Athenaeum. Copenhagen: Danish school of education. pp. 749–59. ISBN 978-87-7684-737-1.

- ^ Skola, J. (1922). "Czech Sociology". American Journal of Sociology. 28 (1): 76–78. doi:10.1086/213427. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2764647.

- ^ Wein, Martin. 2015. History of the Jews in the Bohemian Lands. Leiden: Brill, pp. 40-43, including Hilsner's biography Table of Contents

- ^ a b c Orzoff 2009, p. 30.

- ^ "Србија некада мамила као Америка". www.novosti.rs.

- ^ Preclík, Vratislav (2019). Masaryk a legie (in Czech). Paris Karviná in association with the Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague. pp. 12–70, 101–102, 124–125, 128–129, 132, 140–148, 184–190. ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3.

- ^ Sistek, Frantisek (January 2019). "Czech-Montenegrin Relations, In: Ladislav Hladký et al., Czech Relations with the Nations and Countries of Southeastern Europe, Zagreb: Srednja Evropa 2019".

- ^ "The feminist legacy of Charlotte and Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk • mujRozhlas". 30 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Orzoff 2009, p. 44.

- ^ Popplewell 1995, p. 237

- ^ Masaryk 1970, pp. 50, 221, 242

- ^ Voska & Irwin 1940, pp. 98, 108, 120, 122–23

- ^ Bose 1971, p. 233

- ^ Orzoff 2009, p. 41.

- ^ Orzoff 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Preclík, Vratislav (2019). Masaryk a legie (in Czech). Paris Karviná in association with the Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague. pp. 87–89, 124–128, 140–148, 184–190. ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3.

- ^ Wein, Martin. 2015. History of the Jews in the Bohemian Lands. Leiden: Brill, p. 60-63, including Masaryk's biography with a focus on Jewish ties, also see 40-46 on Hilsner Trial itself Table of Contents

- ^ Láníček, Jan (2013). Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938–48: Beyond Idealisation and Condemnation. New York: Springer. pp. 4, 10. ISBN 978-1-137-31747-6.

Later on, Masaryk repeated the same story, only instead of using 'partly managed' he used the phrase 'a great influence on newspapers in all the Allied countries'. The great philosopher and humanist Masaryk was still using the same anti-Semitic trope found at the bottom of all anti-Jewish accusations.

- ^ Orzoff 2009, p. 140.

- ^ Orzoff 2009, p. 123.

- ^ Preclík, Vratislav: K stému výročí vzniku Masarykovy akademie práce (One hundred years of the Masaryk Academy of Labour), in Strojař (The Machinist): Journal of MA, časopis Masarykovy akademie práce, January–June 2020, year XXIX., issue 1, 2., ISSN 1213-0591, registrace Ministerstva kultury ČR E13559, pp. 2–20

- ^ Proceedings from 1.PIMCO "Encyclopedy of Performance", 2500 pages (3 volumes "Man", "Production", "Business") Masaryk Academy of Labour, Prague 1924 - 1926

- ^ "Thomas Garriue Masaryk – Public Art and Architecture from Around the World".

- ^ http://www.mzv.cz/public/60/43/b3/1 44368_14893_odhaleni.jpg Photo of the unveiling by the President of the City Government Rosario Robles and the Lord Mayor of the City of Prague Jan Kasl

- ^ "Statue of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk". Prague.eu The Official Tourist Website for Prague. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Blackstone, Lillian (23 March 1952). "Into center of state". St. Petersburg Times. p. 19. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- ^ Martin Wein, A History of Czechs and Jews: A Slavic Jerusalem. London: Routledge, 2015, specifically pp. 50-63 [1]

- ^ "KKL Czech Presidents' Birthday".

- ^ Plan of the City Center, Genf 2000 (Thomas Masaryk Chemin)

- ^ "(1841) Masaryk". Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. 2003. p. 147. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_1842. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7.

- ^ Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. p. 369.

- ^ "Řády a vyznamenání prezidentů republiky" (in Czech). vyznamenani.net. 18 December 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- ^ Masaryk, T. G.: Otázka sociální, Praha 1896, German 1898 Otázka sociální: základy marxismu filosofické a sociologické I. a II., MÚ AV ČR, Praha 2000 (6. č. vyd.).

- ^ see publications: Charlotta Garrigue Masaryková (Charlie Masaryková): „O Bedřichu Smetanovi“ (About B. Smetana), články v Naší době 1893 (Articles in Journal „Naše doba“ 1893), Epilogue Miloslav Malý, Masarykovo demokratické hnutí (issued by Masaryk's Democratic Movement, Prague, 2-nd edition), Praha 1993

- ^ "Masarykův vztah k náboženství" (in Czech). rozhlas.cz. 7 March 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Francisca de Haan; Krasimira Daskalova; Anna Loutfi (2006). Biographical Dictionary of Women's Movements and Feminisms in Central, Eastern, and South Eastern Europe: 19th and 20th Centuries. Central European University Press. pp. 306–. ISBN 978-963-7326-39-4. Retrieved 7 August 2013.

Sources and further reading

edit- Bose, A. C. (1971). Indian Revolutionaries Abroad, 1905–1927. Patna: Bharati Bhawan. ISBN 81-7211-123-1.

- Čapek, Karel. (1931–35). Hovory s T. G. Masarykem [Conversations with T. G. Masaryk]. Prague. (English translations: President Masaryk Tells His Story, tr. M. and R. Weatherall, London, 1934; and Masaryk on Thought and Life, London, 1938)

- Masaryk, T. (1970). Making of a State. Howard Fertig. ISBN 0-685-09575-4.

- Orzoff, Andrea (2009). Battle for the Castle: The Myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe, 1914–1948. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536781-2.

- Popplewell, Richard J (1995). Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire 1904–1924. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-4580-3. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- Preclík, Vratislav (2019). Masaryk a legie (in Czech). Paris Karviná in association with the Masaryk Democratic Movement, Prague. p. 219. ISBN 978-80-87173-47-3.

- Voska, E.V; Irwin, W (1940). Spy and Counterspy. New York. Doubleday, Doran & Co.

- Walzel, Vladimir S.; Polak, Frantisek; Solar, Jiri (1960). T. G. Masaryk – Champion of Liberty. Research and Studies Center of CFTUF, New York.

- Wein, Martin. A History of Czechs and Jews: A Slavic Jerusalem. London: Routledge, 2015, 40-65 specifically on T.G. Masaryk and Jews [4]

- Wiskemann, Elizabeth. "Masaryk and Czechoslovakia," History Today (Dec 1968), Vol. 18 Issue 12, pp 844–851 online

External links

edit- Works by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk available online and for download from the catalogue of the Municipal Library in Prague Archived 2017-02-22 at the Wayback Machine (in Czech).

- Thomas G. Masaryk Papers

- Works by or about Tomáš Masaryk at the Internet Archive

- Newspaper clippings about Tomáš Masaryk in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW