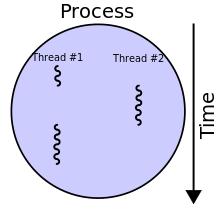

In computer science, a thread of execution is the smallest sequence of programmed instructions that can be managed independently by a scheduler, which is typically a part of the operating system.[1] In many cases, a thread is a component of a process.

Scheduling, Preemption, Context Switching

The multiple threads of a given process may be executed concurrently (via multithreading capabilities), sharing resources such as memory, while different processes do not share these resources. In particular, the threads of a process share its executable code and the values of its dynamically allocated variables and non-thread-local global variables at any given time.

The implementation of threads and processes differs between operating systems.[2][page needed]

History

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (February 2021) |

Threads made an early appearance under the name of "tasks" in IBM's batch processing operating system, OS/360, in 1967. It provided users with three available configurations of the OS/360 control system, of which Multiprogramming with a Variable Number of Tasks (MVT) was one. Saltzer (1966) credits Victor A. Vyssotsky with the term "thread".[3]

The use of threads in software applications became more common in the early 2000s as CPUs began to utilize multiple cores. Applications wishing to take advantage of multiple cores for performance advantages were required to employ concurrency to utilize the multiple cores.[4]

Related concepts

editScheduling can be done at the kernel level or user level, and multitasking can be done preemptively or cooperatively. This yields a variety of related concepts.

Processes

editAt the kernel level, a process contains one or more kernel threads, which share the process's resources, such as memory and file handles – a process is a unit of resources, while a thread is a unit of scheduling and execution. Kernel scheduling is typically uniformly done preemptively or, less commonly, cooperatively. At the user level a process such as a runtime system can itself schedule multiple threads of execution. If these do not share data, as in Erlang, they are usually analogously called processes,[5] while if they share data they are usually called (user) threads, particularly if preemptively scheduled. Cooperatively scheduled user threads are known as fibers; different processes may schedule user threads differently. User threads may be executed by kernel threads in various ways (one-to-one, many-to-one, many-to-many). The term "light-weight process" variously refers to user threads or to kernel mechanisms for scheduling user threads onto kernel threads.

A process is a "heavyweight" unit of kernel scheduling, as creating, destroying, and switching processes is relatively expensive. Processes own resources allocated by the operating system. Resources include memory (for both code and data), file handles, sockets, device handles, windows, and a process control block. Processes are isolated by process isolation, and do not share address spaces or file resources except through explicit methods such as inheriting file handles or shared memory segments, or mapping the same file in a shared way – see interprocess communication. Creating or destroying a process is relatively expensive, as resources must be acquired or released. Processes are typically preemptively multitasked, and process switching is relatively expensive, beyond basic cost of context switching, due to issues such as cache flushing (in particular, process switching changes virtual memory addressing, causing invalidation and thus flushing of an untagged translation lookaside buffer (TLB), notably on x86).

Kernel threads

editA kernel thread is a "lightweight" unit of kernel scheduling. At least one kernel thread exists within each process. If multiple kernel threads exist within a process, then they share the same memory and file resources. Kernel threads are preemptively multitasked if the operating system's process scheduler is preemptive. Kernel threads do not own resources except for a stack, a copy of the registers including the program counter, and thread-local storage (if any), and are thus relatively cheap to create and destroy. Thread switching is also relatively cheap: it requires a context switch (saving and restoring registers and stack pointer), but does not change virtual memory and is thus cache-friendly (leaving TLB valid). The kernel can assign one or more software threads to each core in a CPU (it being able to assign itself multiple software threads depending on its support for multithreading), and can swap out threads that get blocked. However, kernel threads take much longer than user threads to be swapped.

User threads

editThreads are sometimes implemented in userspace libraries, thus called user threads. The kernel is unaware of them, so they are managed and scheduled in userspace. Some implementations base their user threads on top of several kernel threads, to benefit from multi-processor machines (M:N model). User threads as implemented by virtual machines are also called green threads.

As user thread implementations are typically entirely in userspace, context switching between user threads within the same process is extremely efficient because it does not require any interaction with the kernel at all: a context switch can be performed by locally saving the CPU registers used by the currently executing user thread or fiber and then loading the registers required by the user thread or fiber to be executed. Since scheduling occurs in userspace, the scheduling policy can be more easily tailored to the requirements of the program's workload.

However, the use of blocking system calls in user threads (as opposed to kernel threads) can be problematic. If a user thread or a fiber performs a system call that blocks, the other user threads and fibers in the process are unable to run until the system call returns. A typical example of this problem is when performing I/O: most programs are written to perform I/O synchronously. When an I/O operation is initiated, a system call is made, and does not return until the I/O operation has been completed. In the intervening period, the entire process is "blocked" by the kernel and cannot run, which starves other user threads and fibers in the same process from executing.

A common solution to this problem (used, in particular, by many green threads implementations) is providing an I/O API that implements an interface that blocks the calling thread, rather than the entire process, by using non-blocking I/O internally, and scheduling another user thread or fiber while the I/O operation is in progress. Similar solutions can be provided for other blocking system calls. Alternatively, the program can be written to avoid the use of synchronous I/O or other blocking system calls (in particular, using non-blocking I/O, including lambda continuations and/or async/await primitives[6]).

Fibers

editFibers are an even lighter unit of scheduling which are cooperatively scheduled: a running fiber must explicitly "yield" to allow another fiber to run, which makes their implementation much easier than kernel or user threads. A fiber can be scheduled to run in any thread in the same process. This permits applications to gain performance improvements by managing scheduling themselves, instead of relying on the kernel scheduler (which may not be tuned for the application). Some research implementations of the OpenMP parallel programming model implement their tasks through fibers.[7][8] Closely related to fibers are coroutines, with the distinction being that coroutines are a language-level construct, while fibers are a system-level construct.

Threads vs processes

editThreads differ from traditional multitasking operating-system processes in several ways:

- processes are typically independent, while threads exist as subsets of a process

- processes carry considerably more state information than threads, whereas multiple threads within a process share process state as well as memory and other resources

- processes have separate address spaces, whereas threads share their address space

- processes interact only through system-provided inter-process communication mechanisms

- context switching between threads in the same process typically occurs faster than context switching between processes

Systems such as Windows NT and OS/2 are said to have cheap threads and expensive processes; in other operating systems there is not so great a difference except in the cost of an address-space switch, which on some architectures (notably x86) results in a translation lookaside buffer (TLB) flush.

Advantages and disadvantages of threads vs processes include:

- Lower resource consumption of threads: using threads, an application can operate using fewer resources than it would need when using multiple processes.

- Simplified sharing and communication of threads: unlike processes, which require a message passing or shared memory mechanism to perform inter-process communication (IPC), threads can communicate through data, code and files they already share.

- Thread crashes a process: due to threads sharing the same address space, an illegal operation performed by a thread can crash the entire process; therefore, one misbehaving thread can disrupt the processing of all the other threads in the application.

Scheduling

editPreemptive vs cooperative scheduling

editOperating systems schedule threads either preemptively or cooperatively. Multi-user operating systems generally favor preemptive multithreading for its finer-grained control over execution time via context switching. However, preemptive scheduling may context-switch threads at moments unanticipated by programmers, thus causing lock convoy, priority inversion, or other side-effects. In contrast, cooperative multithreading relies on threads to relinquish control of execution, thus ensuring that threads run to completion. This can cause problems if a cooperatively multitasked thread blocks by waiting on a resource or if it starves other threads by not yielding control of execution during intensive computation.

Single- vs multi-processor systems

editUntil the early 2000s, most desktop computers had only one single-core CPU, with no support for hardware threads, although threads were still used on such computers because switching between threads was generally still quicker than full-process context switches. In 2002, Intel added support for simultaneous multithreading to the Pentium 4 processor, under the name hyper-threading; in 2005, they introduced the dual-core Pentium D processor and AMD introduced the dual-core Athlon 64 X2 processor.

Systems with a single processor generally implement multithreading by time slicing: the central processing unit (CPU) switches between different software threads. This context switching usually occurs frequently enough that users perceive the threads or tasks as running in parallel (for popular server/desktop operating systems, maximum time slice of a thread, when other threads are waiting, is often limited to 100–200ms). On a multiprocessor or multi-core system, multiple threads can execute in parallel, with every processor or core executing a separate thread simultaneously; on a processor or core with hardware threads, separate software threads can also be executed concurrently by separate hardware threads.

Threading models

edit1:1 (kernel-level threading)

editThreads created by the user in a 1:1 correspondence with schedulable entities in the kernel[9] are the simplest possible threading implementation. OS/2 and Win32 used this approach from the start, while on Linux the GNU C Library implements this approach (via the NPTL or older LinuxThreads). This approach is also used by Solaris, NetBSD, FreeBSD, macOS, and iOS.

M:1 (user-level threading)

editAn M:1 model implies that all application-level threads map to one kernel-level scheduled entity;[9] the kernel has no knowledge of the application threads. With this approach, context switching can be done very quickly and, in addition, it can be implemented even on simple kernels which do not support threading. One of the major drawbacks, however, is that it cannot benefit from the hardware acceleration on multithreaded processors or multi-processor computers: there is never more than one thread being scheduled at the same time.[9] For example: If one of the threads needs to execute an I/O request, the whole process is blocked and the threading advantage cannot be used. The GNU Portable Threads uses User-level threading, as does State Threads.

M:N (hybrid threading)

editM:N maps some M number of application threads onto some N number of kernel entities,[9] or "virtual processors." This is a compromise between kernel-level ("1:1") and user-level ("N:1") threading. In general, "M:N" threading systems are more complex to implement than either kernel or user threads, because changes to both kernel and user-space code are required[clarification needed]. In the M:N implementation, the threading library is responsible for scheduling user threads on the available schedulable entities; this makes context switching of threads very fast, as it avoids system calls. However, this increases complexity and the likelihood of priority inversion, as well as suboptimal scheduling without extensive (and expensive) coordination between the userland scheduler and the kernel scheduler.

Hybrid implementation examples

edit- Scheduler activations used by older versions of the NetBSD native POSIX threads library implementation (an M:N model as opposed to a 1:1 kernel or userspace implementation model)

- Light-weight processes used by older versions of the Solaris operating system

- Marcel from the PM2 project.

- The OS for the Tera-Cray MTA-2

- The Glasgow Haskell Compiler (GHC) for the language Haskell uses lightweight threads which are scheduled on operating system threads.

History of threading models in Unix systems

editSunOS 4.x implemented light-weight processes or LWPs. NetBSD 2.x+, and DragonFly BSD implement LWPs as kernel threads (1:1 model). SunOS 5.2 through SunOS 5.8 as well as NetBSD 2 to NetBSD 4 implemented a two level model, multiplexing one or more user level threads on each kernel thread (M:N model). SunOS 5.9 and later, as well as NetBSD 5 eliminated user threads support, returning to a 1:1 model.[10] FreeBSD 5 implemented M:N model. FreeBSD 6 supported both 1:1 and M:N, users could choose which one should be used with a given program using /etc/libmap.conf. Starting with FreeBSD 7, the 1:1 became the default. FreeBSD 8 no longer supports the M:N model.

Single-threaded vs multithreaded programs

editIn computer programming, single-threading is the processing of one command at a time.[11] In the formal analysis of the variables' semantics and process state, the term single threading can be used differently to mean "backtracking within a single thread", which is common in the functional programming community.[12]

Multithreading is mainly found in multitasking operating systems. Multithreading is a widespread programming and execution model that allows multiple threads to exist within the context of one process. These threads share the process's resources, but are able to execute independently. The threaded programming model provides developers with a useful abstraction of concurrent execution. Multithreading can also be applied to one process to enable parallel execution on a multiprocessing system.

Multithreading libraries tend to provide a function call to create a new thread, which takes a function as a parameter. A concurrent thread is then created which starts running the passed function and ends when the function returns. The thread libraries also offer data synchronization functions.

Threads and data synchronization

edit

Threads in the same process share the same address space. This allows concurrently running code to couple tightly and conveniently exchange data without the overhead or complexity of an IPC. When shared between threads, however, even simple data structures become prone to race conditions if they require more than one CPU instruction to update: two threads may end up attempting to update the data structure at the same time and find it unexpectedly changing underfoot. Bugs caused by race conditions can be very difficult to reproduce and isolate.

To prevent this, threading application programming interfaces (APIs) offer synchronization primitives such as mutexes to lock data structures against concurrent access. On uniprocessor systems, a thread running into a locked mutex must sleep and hence trigger a context switch. On multi-processor systems, the thread may instead poll the mutex in a spinlock. Both of these may sap performance and force processors in symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) systems to contend for the memory bus, especially if the granularity of the locking is too fine.

Other synchronization APIs include condition variables, critical sections, semaphores, and monitors.

Thread pools

editA popular programming pattern involving threads is that of thread pools where a set number of threads are created at startup that then wait for a task to be assigned. When a new task arrives, it wakes up, completes the task and goes back to waiting. This avoids the relatively expensive thread creation and destruction functions for every task performed and takes thread management out of the application developer's hand and leaves it to a library or the operating system that is better suited to optimize thread management.

Multithreaded programs vs single-threaded programs pros and cons

editMultithreaded applications have the following advantages vs single-threaded ones:

- Responsiveness: multithreading can allow an application to remain responsive to input. In a one-thread program, if the main execution thread blocks on a long-running task, the entire application can appear to freeze. By moving such long-running tasks to a worker thread that runs concurrently with the main execution thread, it is possible for the application to remain responsive to user input while executing tasks in the background. On the other hand, in most cases multithreading is not the only way to keep a program responsive, with non-blocking I/O and/or Unix signals being available for obtaining similar results.[13]

- Parallelization: applications looking to use multicore or multi-CPU systems can use multithreading to split data and tasks into parallel subtasks and let the underlying architecture manage how the threads run, either concurrently on one core or in parallel on multiple cores. GPU computing environments like CUDA and OpenCL use the multithreading model where dozens to hundreds of threads run in parallel across data on a large number of cores. This, in turn, enables better system utilization, and (provided that synchronization costs don't eat the benefits up), can provide faster program execution.

Multithreaded applications have the following drawbacks:

- Synchronization complexity and related bugs: when using shared resources typical for threaded programs, the programmer must be careful to avoid race conditions and other non-intuitive behaviors. In order for data to be correctly manipulated, threads will often need to rendezvous in time in order to process the data in the correct order. Threads may also require mutually exclusive operations (often implemented using mutexes) to prevent common data from being read or overwritten in one thread while being modified by another. Careless use of such primitives can lead to deadlocks, livelocks or races over resources. As Edward A. Lee has written: "Although threads seem to be a small step from sequential computation, in fact, they represent a huge step. They discard the most essential and appealing properties of sequential computation: understandability, predictability, and determinism. Threads, as a model of computation, are wildly non-deterministic, and the job of the programmer becomes one of pruning that nondeterminism."[14]

- Being untestable. In general, multithreaded programs are non-deterministic, and as a result, are untestable. In other words, a multithreaded program can easily have bugs which never manifest on a test system, manifesting only in production.[15][14] This can be alleviated by restricting inter-thread communications to certain well-defined patterns (such as message-passing).

- Synchronization costs. As thread context switch on modern CPUs can cost up to 1 million CPU cycles,[16] it makes writing efficient multithreading programs difficult. In particular, special attention has to be paid to avoid inter-thread synchronization from being too frequent.

Programming language support

editMany programming languages support threading in some capacity.

- IBM PL/I(F) included support for multithreading (called multitasking) as early as in the late 1960s, and this was continued in the Optimizing Compiler and later versions. The IBM Enterprise PL/I compiler introduced a new model "thread" API. Neither version was part of the PL/I standard.

- Many implementations of C and C++ support threading, and provide access to the native threading APIs of the operating system. A standardized interface for thread implementation is POSIX Threads (Pthreads), which is a set of C-function library calls. OS vendors are free to implement the interface as desired, but the application developer should be able to use the same interface across multiple platforms. Most Unix platforms, including Linux, support Pthreads. Microsoft Windows has its own set of thread functions in the process.h interface for multithreading, like beginthread.

- Some higher level (and usually cross-platform) programming languages, such as Java, Python, and .NET Framework languages, expose threading to developers while abstracting the platform specific differences in threading implementations in the runtime. Several other programming languages and language extensions also try to abstract the concept of concurrency and threading from the developer fully (Cilk, OpenMP, Message Passing Interface (MPI)). Some languages are designed for sequential parallelism instead (especially using GPUs), without requiring concurrency or threads (Ateji PX, CUDA).

- A few interpreted programming languages have implementations (e.g., Ruby MRI for Ruby, CPython for Python) which support threading and concurrency but not parallel execution of threads, due to a global interpreter lock (GIL). The GIL is a mutual exclusion lock held by the interpreter that can prevent the interpreter from simultaneously interpreting the application's code on two or more threads at once. This effectively limits the parallelism on multiple core systems. It also limits performance for processor-bound threads (which require the processor), but doesn't effect I/O-bound or network-bound ones as much. Other implementations of interpreted programming languages, such as Tcl using the Thread extension, avoid the GIL limit by using an Apartment model where data and code must be explicitly "shared" between threads. In Tcl each thread has one or more interpreters.

- In programming models such as CUDA designed for data parallel computation, an array of threads run the same code in parallel using only its ID to find its data in memory. In essence, the application must be designed so that each thread performs the same operation on different segments of memory so that they can operate in parallel and use the GPU architecture.

- Hardware description languages such as Verilog have a different threading model that supports extremely large numbers of threads (for modeling hardware).

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lamport, Leslie (September 1979). "How to Make a Multiprocessor Computer That Correctly Executes Multiprocess Programs" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-28 (9): 690–691. doi:10.1109/tc.1979.1675439. S2CID 5679366.

- ^ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1992). Modern Operating Systems. Prentice-Hall International Editions. ISBN 0-13-595752-4.

- ^ Saltzer, Jerome Howard (July 1966). Traffic Control in a Multiplexed Computer System (PDF) (Doctor of Science thesis). p. 20.

- ^ Sutter, Herb (March 2005). "The Free Lunch Is Over: A Fundamental Turn Toward Concurrency in Software". Dr. Dobb's Journal. 30 (3).

- ^ "Erlang: 3.1 Processes".

- ^ Ignatchenko, Sergey. Eight Ways to Handle Non-blocking Returns in Message-passing Programs: from C++98 via C++11 to C++20. CPPCON. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Ferat, Manuel; Pereira, Romain; Roussel, Adrien; Carribault, Patrick; Steffenel, Luiz-Angelo; Gautier, Thierry (September 2022). "Enhancing MPI+OpenMP Task Based Applications for Heterogeneous Architectures with GPU support" (PDF). OpenMP in a Modern World: From Multi-device Support to Meta Programming. IWOMP 2022: 18th International Workshop on OpenMP. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 13527. pp. 3–16. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-15922-0_1. ISBN 978-3-031-15921-3. S2CID 251692327.

- ^ Iwasaki, Shintaro; Amer, Abdelhalim; Taura, Kenjiro; Seo, Sangmin; Balaji, Pavan. BOLT: Optimizing OpenMP Parallel Regions with User-Level Threads (PDF). The 28th International Conference on Parallel Architectures and Compilation Techniques.

- ^ a b c d Silberschatz, Abraham; Galvin, Peter Baer; Gagne, Greg (2013). Operating system concepts (9th ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 170–171. ISBN 9781118063330.

- ^ "Multithreading in the Solaris Operating Environment" (PDF). 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 26, 2009.

- ^ Menéndez, Raúl; Lowe, Doug (2001). Murach's CICS for the COBOL Programmer. Mike Murach & Associates. p. 512. ISBN 978-1-890774-09-7.

- ^ O'Hearn, Peter William; Tennent, R. D. (1997). ALGOL-like languages. Vol. 2. Birkhäuser Verlag. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-8176-3937-2.

- ^ Ignatchenko, Sergey (August 2010). "Single-Threading: Back to the Future?". Overload (97). ACCU: 16–19.

- ^ a b Lee, Edward (January 10, 2006). "The Problem with Threads". UC Berkeley.

- ^ Ignatchenko, Sergey (August 2015). "Multi-threading at Business-logic Level is Considered Harmful". Overload (128). ACCU: 4–7.

- ^ 'No Bugs' Hare (12 September 2016). "Operation Costs in CPU Clock Cycles".

Further reading

edit- David R. Butenhof: Programming with POSIX Threads, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-63392-2

- Bradford Nichols, Dick Buttlar, Jacqueline Proulx Farell: Pthreads Programming, O'Reilly & Associates, ISBN 1-56592-115-1

- Paul Hyde: Java Thread Programming, Sams, ISBN 0-672-31585-8

- Jim Beveridge, Robert Wiener: Multithreading Applications in Win32, Addison-Wesley, ISBN 0-201-44234-5

- Uresh Vahalia: Unix Internals: the New Frontiers, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-101908-2