Thunderball is the ninth book in Ian Fleming's James Bond series, and the eighth full-length Bond novel. It was first published in the UK by Jonathan Cape on 27 March 1961, where the initial print run of 50,938 copies quickly sold out. The first novelisation of an unfilmed James Bond screenplay, it was born from a collaboration by five people: Ian Fleming, Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham, Ivar Bryce and Ernest Cuneo, although the controversial shared credit of Fleming, McClory and Whittingham was the result of a courtroom decision.

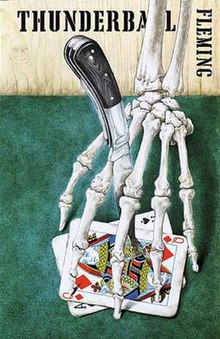

First edition cover, published by Jonathan Cape | |

| Author | Ian Fleming Kevin McClory (Initially uncredited) Jack Whittingham (Initially uncredited) |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping (Jonathan Cape ed.) |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

Publication date | 27 March 1961 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 253 |

| Preceded by | For Your Eyes Only |

| Followed by | The Spy Who Loved Me |

The story centres on the theft of a pair of nuclear weapons by the crime syndicate SPECTRE and the subsequent attempted blackmail of the Western powers for their return. James Bond, Secret Service operative 007, travels to the Bahamas to work with his friend Felix Leiter, seconded back into the CIA for the investigation. Thunderball also introduces SPECTRE's leader Ernst Stavro Blofeld, in the first of three appearances in Bond novels, with On Her Majesty's Secret Service and You Only Live Twice being the others.

Thunderball has been adapted four times, once in a comic strip format for the Daily Express newspaper, twice for the cinema and once for the radio. The Daily Express strip was cut short on the order of its owner, Lord Beaverbrook, after Ian Fleming signed an agreement with The Sunday Times to publish a short story. On screen, Thunderball was released in 1965 as the fourth film in the Eon Productions series, with Sean Connery as James Bond. The second adaptation, Never Say Never Again, was released as an independent production in 1983 also starring Connery as Bond and was produced by Kevin McClory. BBC Radio 4 aired an adaptation in December 2016, directed by Martin Jarvis. It starred Toby Stephens as Bond and Tom Conti as Largo.

Plot

editDuring a meeting with his superior, M, Bond learns that his latest physical assessment is poor because of excessive drinking and smoking. M sends Bond to a health clinic for a two-week treatment to improve his condition. At the clinic Bond encounters Count Lippe, a member of the Red Lightning Tong criminal organisation from Macau. When Bond learns of the Tong connection, Lippe tries to kill him by tampering with a spinal traction table on which Bond is being treated. Bond is saved by nurse Patricia Fearing and later retaliates by trapping Lippe in a steam bath, causing second-degree burns and sending him to hospital for a week.

The Prime Minister receives a communiqué from SPECTRE (Special Executive for Counter-intelligence, Terrorism, Revenge and Extortion), a private criminal enterprise under the command of Ernst Stavro Blofeld. SPECTRE has hijacked a Villiers Vindicator and seized its two nuclear bombs, which it will use to destroy two major targets in the Western Hemisphere unless a ransom is paid. Lippe was dispatched to the clinic to oversee Giuseppe Petacchi, an Italian Air Force pilot stationed at a nearby bomber squadron base, and post the communiqué once the bombs were in SPECTRE's possession. Although Lippe has accomplished his tasks, Blofeld considers him unreliable because of his childish clash with Bond and has him killed.

Acting as a NATO observer of Royal Air Force procedure, Petacchi is in SPECTRE's pay to hijack the bomber in mid-flight by killing its crew and flying it to the Bahamas, where he ditches it in the ocean and it sinks in shallow water. SPECTRE crew members kill Petacchi, camouflage the wreck, and transfer the nuclear bombs onto the cruiser yacht Disco Volante for transport to an underwater hiding place. Emilio Largo, second-in-command of SPECTRE, oversees the operations.

The Americans and the British launch Operation Thunderball to foil SPECTRE and recover the two atomic bombs. On a hunch, M assigns Bond to the Bahamas to investigate. There, Bond meets Felix Leiter, who has been recalled to duty by the CIA from the Pinkerton detective agency because of the Thunderball crisis. While in Nassau, Bond meets Dominetta "Domino" Vitali, Largo's mistress and Petacchi's sister. She is living on board the Disco Volante and believes Largo is on a treasure hunt, although Largo makes her stay ashore while he and his partners supposedly survey the ocean for treasure. After seducing her, Bond informs her that Largo arranged her brother's death, and Bond recruits her to spy on Largo. Domino re-boards the Disco Volante with a Geiger counter disguised as a camera, to ascertain if the yacht has been used to transport the bombs. However, she is discovered and Largo tortures her for information.

Bond and Leiter alert the Thunderball war room of their suspicions of Largo and join the crew of the American nuclear submarine Manta as the ransom deadline nears. The Manta chases the Disco Volante to capture it and recover the bombs en route to the first target. Bond and Leiter lead a dive team in a fight against Largo's crew and a battle ensues. Bond stops Largo from escaping with the bombs; Largo corners him in an underwater cave and is about to kill him, only to be killed by Domino with a shot from a spear gun. The fight leaves six American divers and ten SPECTRE men dead, including Largo, and the bombs are recovered safely. As Bond recuperates in hospital, Leiter explains that Domino told Largo nothing under torture and later escaped from the Disco Volante to get revenge on him. Learning that she is also recovering from injuries, Bond crawls into her room and falls asleep at her bedside.

Characters and themes

editAccording to continuation Bond author Raymond Benson, there was further development of the Bond character in Thunderball, with glimpses of both his sense of humour and his own sense of mortality.[1] Felix Leiter had his largest role to date in a Bond story and much of his humour came through,[2] while his incapacity, suffered in Live and Let Die, had not led to bitterness or to his being unable to join in with the underwater fight scene towards the end of the novel.[2]

Academic Christoph Linder sees Thunderball as part of the second wave of Bond villains: the first wave consisted of SMERSH, the second of Blofeld and SPECTRE, undertaken because of the thawing of relations between East and West,[3] although the cold war escalated again shortly afterwards, with the Bay of Pigs Invasion, the construction of the Berlin Wall and the Cuban Missile Crisis all occurring in an eighteen-month period from April 1961 to November 1962.[4] The introduction of SPECTRE and its use over several books gives a measure of continuity to the remaining stories in the series, according to academic Jeremy Black.[5] Black argues that SPECTRE represents "evil unconstrained by ideology"[6] and it partly came about because the decline of the British Empire led to a lack of certainty in Fleming's mind.[6] This is reflected in Bond's using US equipment and personnel in the novel, such as the Geiger counter and nuclear submarine.[7]

Background

editAs with the previous novels in the series, aspects of Thunderball come from Fleming's own experiences: the visit to the health clinic was inspired by his own 1955 trip to the Enton Hall health farm near Godalming[8] and Bond's medical record, as read out to him by M, is a slightly modified version of Fleming's own.[9] The name of the health farm, Shrublands, was taken from that of a house owned by the parents of his wife's friend, Peter Quennell.[10] Fleming dedicates a quarter of the novel to the Shrublands setting and the naturalist cure Bond undergoes.[11]

Bond's examination of the hull of Disco Volante was inspired by the ill-fated mission undertaken on 19 April 1956 by the ex-Royal Navy frogman "Buster" Crabb on behalf of MI6, as he examined the hull of the Soviet cruiser Ordzhonikidze that had brought Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin on a diplomatic mission to Britain. Crabb disappeared in Portsmouth Harbour and was never seen again.[12] As well as having Buster Crabb in mind, Fleming would also recall the information about the 10th Light Flotilla, an elite unit of Italian navy frogmen who used wrecked ships in Gibraltar to launch attacks on Allied shipping.[13] The specifications for Disco Volante herself had been obtained by Fleming from the Italian ship designer, Leopold Rodriguez.[14]

As often happened in Fleming's novels, several names were taken from those of people he had known. Ernst Stavro Blofeld's name partially comes from Tom Blofeld, a Norfolk farmer and a fellow member of Fleming's club Boodle's, who was a contemporary of Fleming's at Eton.[15] Tom Blofeld's son is Henry Blofeld, a sports journalist, best known as a cricket commentator for Test Match Special on BBC Radio.[16] When Largo rents his beachside villa, it is from "an Englishman named Bryce", whose name was taken from Old Etonian Ivar Bryce, Fleming's friend, who had a beachside property in Jamaica called Xanadu.[10]

Other names used by Fleming included a colleague at The Sunday Times, Robert Harling, who was transformed into Commissioner of Police Harling, whilst an ex-colleague from his stock broking days, Hugo Pitman, became Chief of Immigration Pitman and Fleming's golfing friend, Bunny Roddick, became Deputy Governor Roddick.[17] The title Thunderball came from a conversation Fleming had about a US atomic test.[14]

Writing and copyright

editChronology

editIn mid-1958 Fleming and his friend, Ivar Bryce, began talking about the possibility of a Bond film. Later that year, Bryce introduced Fleming to a young Irish writer and director, Kevin McClory, and the three of them, together with Fleming and Bryce's friend Ernest Cuneo, formed the partnership Xanadu Productions,[18] named after Bryce's Bahamian home,[19] but which was never actually formed into a company.[20] In May 1959 Fleming, Bryce, Cuneo and McClory met first at Bryce's Essex house and then in McClory's London home as they came up with a story outline[21] which was based on an aeroplane full of celebrities and a female lead called Fatima Blush.[22] McClory was fascinated by the underwater world and wanted to make a film that included it.[18] Over the next few months, as the story changed, there were ten outlines, treatments and scripts.[21] Several titles were proposed for these works, including SPECTRE, James Bond of the Secret Service and Longitude 78 West.[23]

Much of the attraction Fleming felt working alongside McClory was based on McClory's film, The Boy and the Bridge,[24] which was the official British entry to the 1959 Venice Film Festival.[19] When the film was released in July 1959, it was poorly received, and did not do well at the box office;[23] Fleming became disenchanted with McClory's ability as a result.[25] In October 1959, with Fleming spending less time on the project,[23] McClory introduced experienced screenwriter Jack Whittingham to the writing process.[26] In November 1959 Fleming left to travel around the world on behalf of The Sunday Times, material for which Fleming also used for his non-fiction travel book, Thrilling Cities.[27] On his travels—through Japan, Hong Kong and into the US—Fleming met with McClory and Ivar Bryce in New York; McClory told Fleming that Whittingham had completed a full outline, which was ready to shoot.[28] Back in Britain in December 1959, Fleming met with McClory and Whittingham for a script conference and shortly afterwards McClory and Whittingham sent Fleming a script, Longitude 78 West, which Fleming considered to be good, although he changed the title to Thunderball.[29]

In January 1960 McClory visited Fleming's Jamaican home Goldeneye, where Fleming explained his intention of delivering the screenplay to MCA, with a recommendation from him and Bryce that McClory act as producer.[30] Fleming also told McClory that if MCA rejected the film because of McClory's involvement, then McClory should either sell his services to MCA, back out of the deal, or file suit in court.[30][31]

Fleming wrote the novel Thunderball at Goldeneye over the period January to March 1960, based on the screenplay written by himself, Whittingham and McClory.[32] In March 1961 McClory read an advance copy of the book and he and Whittingham immediately petitioned the High Court in London for an injunction to stop publication.[33] The plagiarism case was heard on 24 March 1961 and allowed the book to be published, although the door was left open for McClory to pursue further action at a later date.[34] He did so and on 19 November 1963 the case of McClory v Fleming was heard at the Chancery Division of the High Court. The case lasted three weeks, during which time Fleming was unwell—suffering a heart attack during the case itself[35]—and, under advice from his friend Ivar Bryce, offered a deal to McClory, settling out of court. McClory gained the literary and film rights for the screenplay, while Fleming was given the rights to the novel, although it had to be recognised as being "based on a screen treatment by Kevin McClory, Jack Whittingham and the Author".[36] On settlement, "Fleming ultimately admitted '[t]hat the novel reproduces a substantial part of the copyright material in the film scripts'; '[t]hat the novel makes use of a substantial number of the incidents and material in the film scripts'; and '[t]hat there is a general similarity of the story of the novel and the story as set out in the said film scripts'."[37] On 12 August 1964, nine months after the trial ended, Fleming suffered another heart attack and died aged 56.[35]

Script elements

editWhen the script was first drafted in May 1959, with the storyline of an aeroplane of celebrities in the Atlantic, it included elements from Fleming's friend Ernie Cuneo, who included ships with underwater trapdoors in their hulls and an underwater battle scene.[38] The Russians were originally the villains,[21] then the Sicilian Mafia, but this was later changed again to the internationally operating criminal organisation, SPECTRE. Both McClory and Fleming claim to have come up with the concept of SPECTRE; Fleming biographer Andrew Lycett and John Cork both note Fleming as the originator of the group, Lycett saying that "[Fleming] proposed that Bond should confront not the Russians but SPECTRE ..."[38] while Cork produced a memorandum in which Fleming called for the change to SPECTRE:

My suggestion on (b) is that SPECTRE, short for Special Executive for Terrorism, Revolution and Espionage, is an immensely powerful organisation armed by ex-members of SMERSH, the Gestapo, the Mafia, and the Black Tong of Peking, which is placing these bombs in NATO bases with the objective of then blackmailing the Western powers for £100 million or else.

Ian Fleming: memo to Whittingham and McClory[39]

Cork also noted that Fleming used the word "spectre" previously: in the fourth novel, Diamonds Are Forever, for a town near Las Vegas called "Spectreville", and for "spektor", the cryptograph decoder in From Russia, with Love. Others, such as continuation Bond author Raymond Benson, disagree, saying that McClory came up with the SPECTRE concept.[21]

Those elements which Fleming used which can be put down to McClory and Whittingham (either separately or together) include the airborne theft of a nuclear bomb,[40] "Jo" Petachi and his sister Sophie, and Jo's death at the hands of Sophie's boss. The remainder of the screenplay was a two-year collaboration among Fleming, Whittingham, McClory, Bryce and Cuneo.[41]

Release and reception

editThe title of the book will be Thunderball. It is immensely long, immensely dull and only your jacket can save it!

Ian Fleming, in a letter to cover artist Richard Chopping[42]

Thunderball was published on 27 March 1961 in the UK as a hardcover edition by publishers Jonathan Cape; it was 253 pages long and cost 15 shillings.[43] 50,938 copies were printed and quickly sold out.[18] Thunderball was published in the US by Viking Press and sold better than any of the previous Bond books.[33] Publishers Jonathan Cape spent £2,000 (£56,233 in 2023 pounds[44]) on advance publicity.[34] Cape sent out 130 review copies to critics and others and 32,000 copies of the novel had been sent to 864 UK booksellers and 603 outside the UK.[34]

Artist Richard Chopping once again provided the cover art for the novel. On 20 July 1960 Fleming wrote to Chopping to ask if he could undertake the art for the next book, agreeing on a fee of 200 guineas, saying that "I will ask [Jonathan Cape] to produce an elegant skeleton hand and an elegant Queen of Hearts. As to the dagger, I really have no strong views. I had thought of the ordinary flick knife as used by teenagers on people like you and me, but if you have a nice dagger in mind please let us use it."[42]

In 2023, Ian Fleming Publications—the company that administers all Fleming's literary works—had the Bond series edited as part of a sensitivity review to remove or reword some racial or ethnic descriptors. The rerelease of the series was for the 70th anniversary of Casino Royale, the first Bond novel.[45]

Reviews

editThunderball was generally well received by the critics; Francis Iles, wrote in The Guardian that it "is a good, tough, straightforward thriller on perfectly conventional lines."[46] Referring to the negative publicity that surrounded Dr. No—in particular the article by Paul Johnson in the New Statesman entitled, "Sex, Snobbery and Sadism"—Iles was left "wondering what all the fuss is about",[46] noting that "there is no more sadism nor sex than is expected of the author of this kind of thriller".[46] Peter Duval Smith, writing in Financial Times, also took the opportunity to defend Fleming's work against negative criticism and specifically named Johnson and his review: "one should not make a cult of Fleming's novels: a day-dream is a day-dream; but nor should one make the mistake of supposing he does not know what he is doing."[47] Duval Smith thought that Thunderball was "an exciting story [...] skilfully told",[47] with "a romantic sub-plot ... and the denouement involves great events"[47] He also considered it "the best written since Diamonds Are Forever, four books back. It has pace and humour and style. The violence is not so unrelenting as usual: an improvement, I think."[47] He also expressed concern for the central character, saying "I was glad to see him [Bond] in such good form. Earlier he seemed to be softening up. He was having bad hangovers on half-a-bottle of whisky a day, which I don't call a lot, unless he wasn't eating properly."[47]

Writing in The Times Literary Supplement, Philip John Stead thought that Fleming "continues uninhibitedly to deploy his story-telling talents within the limits of the Commander Bond formula."[48] Stead saw that the hijacking of the two bombs "gives Bond some anxiety but, needless to say, does not prevent him from having a good deal of fun in luxury surroundings",[48] whilst "the usual beatings-up, modern style, are ingeniously administered to lady and gentleman like".[48] As to why the novels were so appealing, Stead considered that "Mr. Fleming's special magic lies in his power to impart sophistication to his mighty nonsense; his fantasies connect with up-to-date and lively knowledge of places and of the general sphere of crime and espionage."[48] Overall, in Stead's opinion, with Thunderball "the mixture, exotic as ever, generates an extravagant and exhilarating tale and Bond connoisseurs will be glad to have it."[48] The critic for The Times wrote that Thunderball "relies for its kicks far less than did Dr. No or Goldfinger on sadism and a slightly condescending sophistication."[43] The upshot, in the critic's opinion, was that "the mixture—of good living, sex and violent action—is as before, but this is a highly polished performance, with an ingenious plot well documented and plenty of excitement."[43]

Writing in The Washington Post, Harold Kneeland noted that Thunderball was "Not top Fleming, but still well ahead of the pack",[49] whilst Charles Poore, writing in The New York Times considered the Bond novels to be "post-Dostoevskian ventures in crime and punishment".[50] Thunderball he found to be "a mystery story, a thriller, a chiller and a pleasure to read."[50] Poore identified aspects of the author's technique to be part of the success, saying "the suspense and the surprises that animate the novel arise from the conceits with which Mr. Fleming decorates his tapestry of thieving and deceiving".[50]

The critic from The Sunday Times considered Fleming to have "a sensational imagination, but informed by style, zest and—above all—knowledge".[51] Anthony Boucher wrote: "As usual, Ian Fleming has less story to tell in 90,000 words than Buchan managed in 40,000; but Thunderball is still an extravagant adventure".[33] The critic for the Daily Herald implored "Hey!—that man is taking his clothes off again. So is the girl ... Can anybody stop this? Unfortunately not. Not this side of the best-seller lists. I don't envy Mr Bond's wealthy creator, Ian Fleming. I wish I could pity him",[51] whilst L.G. Offord considered Thunderball to be "just about as wild as ever, with a walloping climax."[33]

Adaptations

edit- Comic strip (1961–1962)

A comic strip adaptation was published daily in the Daily Express newspaper and syndicated worldwide, beginning on 11 December 1961.[52] The owner of the Daily Express, Lord Beaverbrook, cancelled the strip[53] on 10 February 1962[52] after Fleming signed an agreement with The Sunday Times for them to publish the short story "The Living Daylights".[53] Thunderball was reprinted in 2005 by Titan Books as part of the Dr. No anthology that also includes Diamonds Are Forever and From Russia, with Love.[54]

- Thunderball (1965)

In 1965 the film Thunderball was released, starring Sean Connery as James Bond. The film was produced as the fourth Eon Productions film and, as well as listing Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman as producers, Kevin McClory was also included in the production team: Broccoli and Saltzman made a deal with McClory, to undertake a joint production of Thunderball, which stopped McClory from making any further version of the novel for a period of ten years following the release of the Eon-produced version.[55] Thunderball premiered in Tokyo on 9 December 1965, grossing $141.2 million at the global box office.[56]

- Never Say Never Again (1983)

In 1983 Kevin McClory produced a version of the Thunderball story, again with Sean Connery as Bond.[57] The film premiered in New York on 7 October 1983,[58] grossing $9.72 million ($30 million in 2023 dollars[59]) on its first weekend,[60] which was reported to be "the best opening record of any James Bond film"[60] up to that point.

- Warhead (1990s)

In the 1990s McClory planned to make another adaptation of the Thunderball story, Warhead 2000 AD, with Timothy Dalton or Liam Neeson in the lead role, but this was eventually dropped.[61][62]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Benson 1988, p. 124.

- ^ a b Benson 1988, p. 126.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 49-50.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 49.

- ^ a b Black 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Black 2005, p. 53-4.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 290.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 164.

- ^ a b Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 197.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 145.

- ^ a b Macintyre 2008, p. 199.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (5 April 2008a). "Bond – the real Bond". The Times. p. 36.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 366.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 17.

- ^ a b Lycett 1996, p. 348.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 349.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 18.

- ^ Pearson 1967, p. 371.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 19.

- ^ Pearson 1967, p. 367.

- ^ Pearson 1967, p. 372-373.

- ^ Pearson 1967, p. 374.

- ^ Pearson 1967, p. 375.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 359.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 231.

- ^ a b Pearson 1967, p. 381.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 22.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 21.

- ^ a b c "Law Report, March 24". The Times. 25 March 1961. p. 12.

- ^ a b Sellers, Robert (30 December 2007). "The battle for the soul of Thunderball". The Sunday Times.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 432.

- ^ Judge M. Margaret McKeown (27 August 2001). "Danjaq et al. v. Sony Corporation et al" (PDF). United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2006. Retrieved 27 November 2006.

- ^ a b Lycett 1996, p. 350.

- ^ "Inside Thunderball by John Cork". Inside Thunderball. Archived from the original on 12 April 2005. Retrieved 18 October 2011.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 365.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 356.

- ^ a b "Fleming on Chopping". Artistic Licence Renewed. 9 July 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2021.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b c "New Fiction". The Times. 30 March 1961. p. 15.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ Simpson, Craig (25 February 2023). "James Bond books edited to remove racist references". The Sunday Telegraph.

- ^ a b c Iles, Francis (7 April 1961). "Criminal Records". The Guardian. p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Duval Smith, Peter (30 March 1961). "No Ethical Frame". Financial Times. p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e Stead, Philip John (31 March 1961). "Mighty Nonsense". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 206.

- ^ Kneeland, Harold (11 June 1961). "MI-5's James Bond and Other Sleuths". The Washington Post. p. E7.

- ^ a b c Poore, Charles (4 July 1961). "Books of the Times". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Chancellor 2005, p. 165.

- ^ a b Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- ^ a b Simpson 2002, p. 21.

- ^ McLusky et al. 2009, p. 287.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 184.

- ^ "Thunderball". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 154.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 156.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ a b Hanauer, Joan (18 October 1983). "Connery Champ". United Press International.

- ^ Rye, Graham (7 December 2006). "Kevin McClory". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- ^ Smith, Liz (21 December 1998). "Remakes on tap". New York Post. p. 14.

Bibliography

edit- Pearson, John (1967). The Life of Ian Fleming: Creator of James Bond. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85283-233-9.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-85286-040-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-85799-783-5.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. London: Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Simpson, Paul (2002). The Rough Guide to James Bond. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-142-5.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- Chapman, James (2009). Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-515-9.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Hern, Anthony; Fleming, Ian (2009). The James Bond Omnibus Vol.1. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-84856-364-3.