Absolute Power is a 1997 American political action thriller film produced by, directed by, and starring Clint Eastwood as a master jewel thief who witnesses the killing of a woman by Secret Service agents.[3] The screenplay by William Goldman is based on the 1996 novel Absolute Power by David Baldacci. Screened at the 1997 Cannes Film Festival,[4] the film also stars Gene Hackman, Ed Harris, Laura Linney, Judy Davis, Scott Glenn, Dennis Haysbert, and Richard Jenkins. It was also the last screen appearance of E. G. Marshall. The scenes in the museum were filmed in the Walters Art Museum, where Whitney is copying a painting of El Greco, "Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata"[5]

| Absolute Power | |

|---|---|

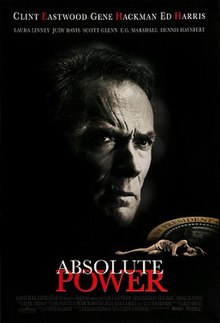

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Clint Eastwood |

| Screenplay by | William Goldman |

| Based on | Absolute Power by David Baldacci |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Jack N. Green |

| Edited by | Joel Cox |

| Music by | Lennie Niehaus |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Releasing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50 million[1] |

| Box office | $92.8 million[2] |

Plot

editIn Washington, D.C., master thief Luther Whitney breaks into the mansion of billionaire Walter Sullivan. He is forced to hide upon the arrival of Sullivan's wife Christy, on a drunken rendezvous with Alan Richmond, the President of the United States. Hidden behind the bedroom vault's one-way mirror, Whitney watches as Richmond becomes sexually violent; Christy, in self-defense, wounds his arm with a letter opener. Richmond screams for help, and Secret Service agents Bill Burton and Tim Collin burst in, see Christy about to stab the President, and fatally shoot her. Chief of Staff Gloria Russell arrives, and they stage the scene to look like a burglary gone wrong. Whitney is unnoticed until he makes his getaway, pursued by the agents, but he manages to escape with millions in valuables as well as the incriminating letter opener.

Detective Seth Frank heads the murder investigation. Though Whitney, known to authorities as a high-profile burglar, becomes a prime suspect, Frank does not believe he is a murderer because he was never a violent criminal. Burton asks Frank to keep him informed on the case and wiretaps Frank's office telephone. Just as Whitney is about to flee the country, he sees Richmond on television publicly commiserating with Sullivan – a close friend and financial supporter of the president – on his loss. Incensed, Whitney decides to bring Richmond to justice.

Whitney's estranged daughter Kate accompanies Frank to Whitney's home in search of clues. Photographs of her indicate that Luther has secretly been watching her as she grew up. Fearing for her father's life, she agrees to set him up, arranging a meeting at an outdoor café. Frank guarantees Whitney's safety, but Burton learns of the plan through the wiretap, and both Collin and Michael McCarty – a hitman hired by a vengeful Sullivan – prepare to kill Whitney. The two snipers, each unaware of the other, try to shoot Whitney when he meets with Kate. Whitney escapes disguised as a police officer. Whitney later explains to Kate exactly how Christy was killed and by whom.

Suspecting that Kate must know the truth, Richmond decides she must be eliminated. When Whitney learns from Frank that the Secret Service is surveilling Kate, he races back to D.C. to protect her. Collin rams Kate's car over a cliff edge. Whitney arrives too late, but Kate survives. Collin tries again to kill her at the hospital with a poison-filled syringe, but is killed by Whitney.

Whitney replaces Sullivan's chauffeur and tells Sullivan what truly happened the night his wife was killed. He gives Sullivan the letter opener with Richmond's blood and fingerprints and drops him off outside the White House. A shocked and enraged Sullivan then enters the building to confront Richmond. Later on television comes the shocking news from Sullivan that Richmond allegedly committed suicide by stabbing himself to death with the letter opener. Meanwhile, Frank discovers that a remorseful Burton has committed suicide and uses the evidence Burton left behind to arrest Russell. Back at the hospital, Whitney reconnects with his daughter.

Cast

edit- Clint Eastwood as Luther Whitney

- Gene Hackman as President Alan Richmond

- Ed Harris as Seth Frank

- Laura Linney as Kate Whitney

- Scott Glenn as Bill Burton

- Dennis Haysbert as Tim Collin

- Judy Davis as Gloria Russell

- E. G. Marshall as Walter Sullivan

- Melora Hardin as Christy Sullivan

- Kenneth Welsh as Sandy Lord

- Penny Johnson as Laura Simon

- Richard Jenkins as Michael McCarty

- Mark Margolis as Red Brandsford

- Alison Eastwood as art student

Production

editThe worldwide book and film rights to the novel were sold for a reported $5 million. William Goldman was hired to write the screenplay in late 1994. He worked on several drafts through 1995, which he later described in his memoir Which Lie Did I Tell?[6]

When Clint Eastwood first heard of the book being turned into a film, he liked the basic plot and the characters, but disliked that most of those he considered interesting were killed off. He requested that Goldman make sure that "everyone the audience likes doesn't get killed off."[7] Absolute Power was filmed between June and August 1996.

Among the Washington, D.C. locations used for filming was the apartment of journalist Christopher Hitchens.[8][9]

Reception

editCritical response

editAbsolute Power was met with mixed reviews from critics. In her review in The New York Times, Janet Maslin gave it a mixed review, writing, "Mr. Eastwood directs a sensible-looking genre film with smooth expertise, but its plot is quietly berserk." Maslin goes on to write, "Mr. Eastwood's own performance sets a high-water mark for laconic intelligence and makes the star seem youthfully spry by joking so much about his age."[10]

On the aggregate reviewer website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 56% based on 57 reviews, with an average rating of 5.7/10. The site's critics consensus reads: "Absolute Power collapses under its preposterous plotting despite an all-star cast and Clint Eastwood's deft direction."[11] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 52 out of 100, based on 21 critics, indicating "mixed or average" reviews.[12] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.

Box office

editThe film grossed $16.8 million in its opening weekend. It grossed $50.1 million in the United States and Canada and $42.7 million internationally for a worldwide total of $92.8 million against its $50 million production budget.[2][1] It Italy, it was number one for nine consecutive weeks.[13]

Soundtrack

editThe soundtrack to Absolute Power was released on March 11, 1997. "Kate's Theme" was composed by Clint Eastwood and arranged by Lennie Niehaus. All other tracks written and arranged by Lennie Niehaus.

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Kate's Theme" | Lennie Niehaus | 2:07 |

| 2. | "Mansion" | Lennie Niehaus | 1:32 |

| 3. | "Christy Dies" | Lennie Niehaus | 2:28 |

| 4. | "Mansion Chase" | Lennie Niehaus | 4:34 |

| 5. | "Christy's Dance" | Lennie Niehaus | 3:42 |

| 6. | "Waiting for Luther/Wait for My Signal" | Lennie Niehaus | 6:58 |

| 7. | "Dr. Kevorkian I Presume" | Lennie Niehaus | 1:44 |

| 8. | "Sullivan's Revenge" | Lennie Niehaus | 2:19 |

| 9. | "Kate's Theme/End Credits" | Lennie Niehaus | 4:42 |

| Total length: | 29:54[14] | ||

References

edit- Citations

- ^ a b "Absolute Power (1997) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Top 125". Variety. February 9, 1998. p. 31.

- ^ "Clint Eastwood Is Returning to Acting". MovieWeb. May 21, 2017. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Absolute Power". Festival de Cannes. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata | the Walters Art Museum".

- ^ Goldman, William, Which Lie Did I Tell?, Bloomsbury, 2000 p 97-127

- ^ Blair, Iain (March 1997). "Clint Eastwood: The Actor-Director Reflects on His Continuing Career and New Film, Absolute Power". Film & Video. 14 (3): 70–78.

- ^ Groth, Gary (January 9, 2012). "My Dinner with Hitch". The Comics Journal. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher. "In Search of the Washington Novel". City Journal. No. Autumn 2010. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (February 14, 1997). "Absolute Power: A Whole New Meaning for Executive Privilege". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2012.

- ^ "Absolute Power (1997)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ "Absolute Power". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "Italy Top 15". Screen International. July 25, 1997. p. 43.

- ^ Absolute Power Soundtrack AllMusic. Retrieved March 2, 2014

- Bibliography

- Baldacci, David (1996). Absolute Power. New York: Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 978-0-446-51996-0.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.