Time Bandits is a 1981 British fantasy adventure film co-written, produced, and directed by Terry Gilliam. It stars David Rappaport, Sean Connery, John Cleese, Shelley Duvall, Ralph Richardson, Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm, Michael Palin, Peter Vaughan and David Warner. The film tells the story of a young boy taken on an adventure through time with a band of thieves who plunder treasure from various points in history.

| Time Bandits | |

|---|---|

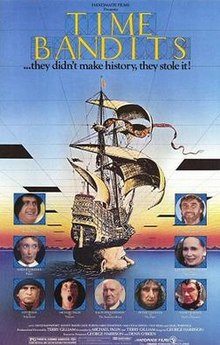

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Terry Gilliam |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Terry Gilliam |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Peter Biziou |

| Edited by | Julian Doyle |

| Music by |

|

Production company | |

| Distributed by | HandMade Films (Distributors) Ltd.[1] |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 113 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5 million[2] |

| Box office | $42.4 million[3] |

In 1979, Terry Gilliam was unable to set up the film Brazil; therefore, he proposed a family film. Time Bandits was co-written with fellow Monty Python Michael Palin, financed by ex-Beatle George Harrison's HandMade Films and filmed in England, Morocco and Wales. The film was released in cinemas on 2 July 1981 in the United Kingdom and on 6 November 1981 in the United States. On its initial release, the film received mainly positive reviews from critics; it opened at number one at the weekend box office in the US and Canada, and, by the end of its run, grossed $36 million on a budget of $5 million.

Gilliam has referred to Time Bandits as the first in his "Trilogy of Imagination", followed by Brazil (1985) and ending with The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988).

Plot

editKevin is a young boy fascinated by history, particularly that of Ancient Greece. His parents ignore his activities, having become obsessed with buying the latest household gadgets. One night, as Kevin is sleeping, an armoured knight on a horse bursts out of his wardrobe. Kevin hides under the covers as the knight rides off into a forest where his bedroom wall was; when Kevin looks again, the room is back to normal and he finds one of his photos on the wall similar to the forest he saw. The next night he prepares a satchel with supplies and a Polaroid camera but is surprised when six dwarfs spill out of the wardrobe. Kevin quickly learns the group has stolen a map and is looking for an exit from his room before they are discovered. They find that the bedroom wall leads to a portal. Kevin is hesitant to join until the apparition of a floating, menacing head—the Supreme Being—appears behind them, demanding the return of the map. Kevin and the dwarves find an empty void at the end of the hallway.

They land in Italy during the Battle of Castiglione. As they recover, Kevin learns that Randall is the lead dwarf of the group, which also includes Fidgit, Strutter, Og, Wally, and Vermin. They were once employed by the Supreme Being to repair holes in the spacetime fabric, but realised the potential to use the map that identifies these holes to steal riches and escape via time/space travel. With Kevin's help, they visit several locations in spacetime and meet figures such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Robin Hood. Kevin uses his camera to document their visits. However, they are unaware that their activities are being monitored by Evil, a malevolent being who is able to manipulate reality and is attempting to acquire the map.

Kevin becomes separated from the group and ends up in Mycenaean Greece, meeting King Agamemnon. After Kevin inadvertently helps Agamemnon kill a Minotaur,[4] the king adopts him. Randall and the others soon locate Kevin and abduct him, much to his resentment, and escape through another hole, arriving on the RMS Titanic. After it sinks, they tread water while arguing with each other. Evil manipulates the group and transports them to his realm, the Time of Legends. After surviving encounters with ogres and a giant, Kevin and the dwarfs locate the Fortress of Ultimate Darkness and are led to believe that "The Most Fabulous Object in the World" awaits them, luring them into Evil's trap. Evil takes the map and locks the group in a cage over a bottomless pit. While looking through the Polaroids he took, Kevin finds one that includes the map, and the group realises that there is a hole near them. They escape from the cage and Kevin distracts their pursuers while the others go through the hole.

Evil confronts Kevin and takes the map from him. The dwarfs return with various warriors and fighting machines from across time, but Evil effortlessly and comically defeats them all. As Kevin and the dwarfs cower, Evil prepares to unleash his ultimate power. Suddenly, he is engulfed in flames and burned into charcoal; from the smoke, a besuited elderly man emerges, revealed as the Supreme Being. He reveals that he allowed the dwarfs to borrow his map and the whole adventure had been a test. He orders the dwarfs to collect the pieces of concentrated Evil, warning that they can be deadly if not contained. After recovering the map he allows the dwarfs to rejoin him in his creation duties. The Supreme Being disappears with the dwarfs, leaving Kevin behind as a missed piece of Evil begins to smoulder.

Kevin awakes in his bedroom to find it filled with smoke. Firefighters break down the door and rescue him as they put out a fire in his house. One of the firemen finds that his parents' new toaster oven caused the fire. As Kevin recovers, he finds one of the firemen resembles Agamemnon and discovers that he still has the photos from his adventure. Kevin's parents discover a smouldering rock in the toaster oven. Recognising it as a piece of Evil, Kevin warns them not to touch it, but they ignore him, do so and explode, leaving only their shoes. As the Agamemnon-firefighter winks at the boy before leaving, Kevin approaches the smoking shoes and is seen from above as his figure grows smaller, revealing the planet and then outer space, before being rolled up in the map by the Supreme Being.

Cast

edit- David Rappaport as Randall

- Kenny Baker as Fidgit

- Malcolm Dixon as Strutter

- Mike Edmonds as Og

- Jack Purvis as Wally

- Tiny Ross as Vermin

- Craig Warnock as Kevin

- John Cleese as Robin Hood

- Sean Connery as Agamemnon/Fireman

- Shelley Duvall as Pansy

- Katherine Helmond as Mrs. Ogre

- Ian Holm as Napoleon

- Michael Palin as Vincent

- Ralph Richardson as Supreme Being

- Peter Vaughan as Winston the Ogre

- David Warner as Evil

- David Daker as Trevor, Kevin's father

- Sheila Fearn as Diane, Kevin's mother

- Jim Broadbent as TV game show host

- John Young as Reginald

- Myrtle Devenish as Beryl

- Terence Bayler as Lucien

- Preston Lockwood as Neguy

- Charles McKeown as Theatre Manager

- Derrick O'Connor as Redgrave

- Neil McCarthy as Marion

- Derek Deadman as Robert

- Jerold Wells as Benson

- Ian Muir as the Giant

- Tony Jay (voice) as the Supreme Being

Production

editDevelopment

editIn November 1979, Terry Gilliam developed the concept for Time Bandits after he had started work on Brazil. Monty Python manager and producer Denis O'Brien had difficulty understanding the concept of Brazil, so Gilliam decided on the idea of a family film. O'Brien had set up HandMade Films in London for the former Beatle George Harrison to produce Life of Brian and the initiative was to produce more films with Python talent. When Gilliam's pitch was accepted he co-wrote the script with fellow Python Michael Palin.[5][6]

Casting

editSean Connery was cast as Agamemnon after he met producer O'Brien on a golf course. A reference in the script introduced the character with the joke description: "Removing his helmet reveals himself to be none other than Sean Connery or an actor of equal but cheaper stature". Connery was a Python fan and agreed to do the role for a nominal fee in return for a share of the gross profits.[7][5]

The part of Robin Hood was originally written for Palin but John Cleese was eventually cast as his name was considered more bankable. Palin decided to appear with Shelley Duvall in the small recurring roles of Vincent and Pansy. Cleese based his performance on the Duke of Kent by watching him having meaningless conversations with footballers at the FA Cup Final during the team line-up before the match. Cleese remarked: "It always struck me as the most extraordinary ritual, the complete futility of that walking up and down thing".[5]

Ralph Richardson's casting as the Supreme Being was because he was regarded "pretty much near God in the acting profession".[8] Richardson took his role seriously, marking out his lines in red ink and occasionally saying, "God wouldn't say that".[5]

Ruth Gordon and Gilda Radner were considered for the role of Mrs. Ogre. Palin felt Gordon was the best choice but she had to drop out after sustaining an injury shooting Any Which Way You Can. The studio wanted Radner considering her bankable, but Gilliam campaigned for Katherine Helmond due to the popularity of the TV comedy Soap.[9][10][11]

Jonathan Pryce was offered the role of Evil but opted for another film (Loophole) for a higher fee as "he was broke" at the time.[12]

Filming

editFilming was partly on location with Raglan Castle standing in for Castiglione delle Stiviere, Epping Forest as Sherwood Forest and Aït Benhaddou as Agamemnon's palace in Mycenae.[13][14] Interior scenes were filmed at Lee International Film Studios.[15] Gilliam said he wanted to film from a "kid's point of view" and therefore shot from a low camera angle. He also said, "fearing a child wouldn't sustain the film ... let's surround him with people of a similar height".[16]

During post-production, Gilliam had argued about changing the story's downbeat ending with O'Brien, who was also pressuring him to include some of Harrison's songs. Harrison eventually wrote and performed the closing credits song "Dream Away". The lyrics contained Harrison's comments on Time Bandits and on Gilliam's behaviour during the making of the film.[17]

Japanese release

editThe theatrical release in Japan was 1983. At cinemas outside of major metropolitan areas, preview screenings were shown as a double feature alongside the domestic production Harmagedon.[18][19] Therefore, for commercial reasons on the part of the distributor who wanted to sell it as a children's programme, editing was carried out in a manner unique to Japan that "neglected the true intent of the work." Part of the scene of Robin Hood and the cannibal couple,[19] and the last scene where the parents disappear were cut, resulting in a running time of approximately 103 minutes, approximately 13 minutes shorter than the original.[20]

The last scene was used uncut when it was aired on TV ("Sunday Western Movie Theater" broadcast on January 10, 1988). Each videogram version (LD, DVD, Blu-ray) released in Japan is the original full-length version.[19]

Reception

editBox office

editThe film was released in the US on 6 November 1981 and opened at number one at the box office for the weekend, grossing $6,507,356 from 821 theatres.[21] The film remained number one for 4 weeks and grossed $36 million in the United States and Canada on a budget of $5 million (£2.2 million), and was the 13th highest-grossing film of the year in North America.[22][23]

The film was re-released in the US on 12 November 1982[24] and grossed a further $6 million[25] to take its gross to $42.4 million in the United States and Canada.[3]

Critical response

editOn the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 91% rating based on 54 reviews, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The consensus states: "Time Bandits is a remarkable time-travel fantasy from Terry Gilliam, who utilises fantastic set design and homemade special effects to create a vivid, original universe".[26] On Metacritic, it received a weighted average rating of 79 out of 100 based on 18 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[27]

The film had mainly positive reviews. Gary Arnold of The Washington Post said it was "a marvellous cinematic tonic, a sumptuous new classic in the tradition of time-travel and fairy-tale adventure".[28] David Ansen of Newsweek considered it "at once sophisticated and childlike in its magical but emotionally cool logic ... a wonderful wild card in the fall movie season".[29] Vincent Canby of The New York Times said it was "a cheerfully irreverent lark – part fairy tale, part science fiction and part comedy".[30]

Other critics gave the film less praise. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times said: "I'm usually fairly certain whether or not I've seen a good movie. But my reaction to Time Bandits was ambiguous. I had great admiration for what was physically placed on the screen ... But I was disappointed by the breathless way the dramatic scenes were handled and by a breakneck pace that undermined the most important element of comedy, which is timing".[31] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune thought it was "an uneven special effects extravaganza ... Unfortunately, there are just too many visits to famous people".[32]

Legacy

editGilliam has referred to Time Bandits as the first in his "Trilogy of Imagination", followed by Brazil (1985) and ending with The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (1988).[33] All are about the "craziness of our awkwardly ordered society and the desire to escape it through whatever means possible".[33] All three films focus on these struggles and attempts to escape them through imagination: Time Bandits through the eyes of a child, Brazil through the eyes of a man in his thirties, and Munchausen through the eyes of an elderly man.[33]

The film is ranked No. 22 on Empire magazine's "The 50 best kids' movies".[34] It is listed as one of Time magazine's "Top 10 Time-Travel Movies".[35]

Game designer Richard Garriott was inspired by Time Bandits while creating the 1982 game Ultima II: The Revenge of the Enchantress, stating that he watched the film about 20 times to create a copy of the time map, as his game would feature a similar mechanic of "time doors" and the game's box even had a similar cloth map inside.[36][37]

Home media

editThe film was originally released in December 1982 on Betamax, VHS, Video 2000 and CED Videodisc in the UK and on VHS in the US the same year.[38][39][40]

In 1997, it was released on LaserDisc by The Criterion Collection and includes commentary by Gilliam and Palin, Cleese, Warner and Warnock. It also includes a Time Bandits Scrapbook.[41]

In 1999, a DVD was released by Criterion with the original 1997 LaserDisc features and the theatrical trailer. The same year Anchor Bay Entertainment released a version with no extras or special features.[42] In 2004, Anchor Bay released the DVD as a Divimax edition on two discs with special features but no commentary. The features include the AFI's 'The Films of Terry Gilliam' documentary; an interview with Gilliam and Palin; theatrical trailers; Gilliam's bio; and a DVD-ROM with the original screenplay and a fold-out Map of the Universe.[42][43]

In 2010, a Blu-ray version was released by Anchor Bay and included an interview with Gilliam and a theatrical trailer.[44] In 2013, a Blu-ray version was released by Arrow Films in the UK. The original 35mm negative was scanned at 2K resolution and the restoration was approved by Gilliam.[45][46] In 2014, a Blu-ray was released by Criterion as a new 2K digital restoration and includes the original commentary from the 1997 LaserDisc by Gilliam and Palin, Cleese, Warner and Warnock; a feature with production designer Milly Burns and costume designer James Acheson; a 1998 conversation between Gilliam and film scholar Peter von Bagh; a 1981 appearance by Shelley Duvall on Tom Snyder's The Tomorrow Show; a photo gallery; the theatrical trailer; and an insert that has a reproduction of the Map of the Universe on one side and an essay by David Sterritt on the other.[47][48][49] In 2023, a 4K UHD version was released by Arrow Films and Criterion, again with the transfer supervised by Gilliam, including the same special features as the earlier 2K version.[50][51][49]

Comic book adaptation

editMarvel Comics published a comic book adaptation of the film in February 1982. It was written by Steve Parkhouse and drawn by David Lloyd and John Stokes.[52]

Planned sequel

editGilliam and Charles McKeown wrote a script for Time Bandits II in 1996 and planned to bring back the original cast, except for David Rappaport and Tiny Ross who had since died. When Jack Purvis died the following year, the sequel was shelved.[53]

Television series

editIn July 2018, it was announced that Apple Inc. had gained rights and closed a deal with Anonymous Content, Paramount Television Studios, and MRC Television to develop a television series version of the Terry Gilliam film, also entitled Time Bandits, to distribute on Apple TV+, with Gilliam on board set to serve only as executive producer (thus in a non-writing production role) and Taika Waititi set to co-write and direct the pilot.[54][55] Lisa Kudrow stars alongside Kal-El Tuck, Charlyne Yi, Tadhg Murphy, Roger Jean Nsengiyumva, Rune Temte, Kiera Thompson and Rachel House.[56]

Production took place in New Zealand in late 2022 and early 2023.[57]

References

edit- ^ a b "Time Bandits". bbfc.co.uk.

- ^ Sellers, Robert (2003). Always Look on the Bright Side of Life: The Inside Story of HandMade Films. Metro. p. 40.

- ^ a b Time Bandits at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "Terry Gilliam Says Sean Connery Was Originally Written Into 'Time Bandits' as a Joke, Yet "Saved My Ass" on Fantasy Film". hollywoodreporter.com. The Hollywood reporter. 2 November 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d Sellers, Robert (17 September 2013). "It's a miracle that Terry Gilliam's Time Bandits even got made". Gizmodo.

- ^ 'Terry Gilliam: Career in 40 Minutes'. Total Film. 14 March 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ 'Gilliam/Palin Interview on Time Bandits, Part 1 of 3'. Oddmartian2. 16 March 2008 – via YouTube.

- ^ 'Gilliam/Palin Interview on Time Bandits, Part 2 of 3'. Oddmartian2. 16 March 2008 – via YouTube.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (22 March 2012). "The Lost Roles of Gilda Radner". Vulture. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018.

- ^ Barnes, Mike (1 March 2019). "Katherine Helmond, the Man-Crazy Mother on 'Who's the Boss?' Dies at 89". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Ar, Gary (15 November 1981). "Terry Gilliam: On the Trail of 'Time Bandits'". Washington Post.

- ^ Riley, Jenelle (5 November 2019). "Jonathan Pryce Revisits 'The Caretaker' and Plays Doctor in 'Hysteria'". backstage.com.

- ^ "Filming Locations for Time Bandits (1981), in Berkshire, Kent, Wales and Morocco". The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations.

- ^ "Time Bandits". reelstreets.com.

- ^ "Time Bandits (1981)". BFI. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016.

- ^ 'Mark Lawson Talks to Terry Gilliam 3/4'. alexomat2. 17 November 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ Robinson, Dom (26 August 2013). "Time Bandits: Special Edition on Blu-ray – The DVDfever Review". DVDfever. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ 角川春樹『試写室の椅子』(角川書店、1985年)p.269

- ^ a b c 映画 バンデットQ (1981)について allcinema映画データベース

- ^ バンデットQ - 作品情報 KINENOTE(キネマ旬報映画データベース)

- ^ Ginsberg, Steven (11 November 1981). "'Bandits' Steal B.O. Thunder From Thin Pack; 'Halloween II' Plunges". Variety. p. 3.

- ^ Walker, Alexander (2005). Icons in the Fire: The Rise and Fall of Practically Everyone in the British Film Industry 1984–2000. Orion Books. p. 12.

- ^ "The Numbers – Top-Grossing Movies of 1981". The Numbers.

- ^ Ginsberg, Steven (17 November 1982). "'Creepshow' Leads B.O. Upswing; 'First Blood' Still Flows Strong". Variety. p. 3.

- ^ Ginsberg, Steven (7 December 1982). "National B.O. Takes Seasonal Dip Over Weekend". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "Time Bandits". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ "Time Bandits". Metacritic.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (6 November 1981). "Time Bandits". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ Ansen, David (9 November 1981). "Time Bandits". Newsweek: 92.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (6 November 1981). "'TIME BANDITS,' A LARK THROUGH THE EONS". The New York Times.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Time Bandits movie review & film summary (1981) | Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (25 December 1981). "Time Bandits". Chicago Tribune: 12.

- ^ a b c Matthews, Jack (1996). "Dreaming Brazil". Essay accompanying The Criterion Collection DVD.

- ^ "The 50 best kids' movies". Empire. 2023.

- ^ "Full List | Top 10 Time-Travel Movies". Time.

- ^ Rausch, Allen (7 May 2004). "From Origin to Destination - Page 1". GameSpy. Retrieved 15 July 2024.

- ^ @RichardGarriott (12 November 2018). "True! Watched it like 20 times with friends all sketching... to find it was not a ms real as I hoped... so, I made a "real" one!" (Tweet). Retrieved 15 July 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ "Time Bandits (Betamax, VHS, Video 2000)". Pre-Certification Video.

- ^ "Time Bandits (CED)". Pre-Certification Video.

- ^ "Time Bandits (US VHS)". vhscollector.com.

- ^ Factory, LaserDisc. "Time Bandits – Criterion LaserDisc". DaDon's.

- ^ a b Williams, Margaret (27 May 2016). "Time Bandits". cinemablend.com.

- ^ "Time Bandits: Divimax Edition (1981)". dvdmg.com.

- ^ "Time Bandits [Blu-Ray] (1981)". www.dvdmg.com.

- ^ "Time Bandits Blu-ray (United Kingdom)". www.blu-ray.com.

- ^ "Time Bandits". Arrow Films UK.

- ^ Dellamorte, Andre (17 January 2015). "Tootsie Criterion Blu-ray Review, Plus Reviews for Time Bandits and The Night Porter". Collider.

- ^ "Time Bandits: Criterion Collection [Blu-Ray] (1981)". www.dvdmg.com.

- ^ a b "Time Bandits". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Cole, Jake (16 June 2023). "'Time Bandits' 4K UHD Blu-ray Review: The Criterion Collection". Slant Magazine.

- ^ "Time Bandits Limited Edition 4K Ultra HD". Arrow Films UK.

- ^ Friedt, Stephan (July 2016). "Marvel at the Movies: The House of Ideas' Hollywood Adaptations of the 1970s and 1980s". Back Issue! (89). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 65.

- ^ Terry Gilliam, David Sterritt, Lucille Rhodes (2004). Terry Gilliam: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 217. ISBN 9781578066247.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (27 July 2018). "Apple Makes Rights Deal To Turn Terry Gilliam's Time Bandits Into TV Series". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ Andreeva, Nellie; D'Alessandro, Anthony (11 March 2019). "Taika Waititi To Co-Write & Direct 'Time Bandits' Series In Works At Apple From Paramount, Anonymous Content & MRC". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Petski, Denise (28 September 2022). "'Time Bandits': Lisa Kudrow To Lead Cast Of Taika Waititi's Apple Series". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 29 September 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (27 June 2022). "Taika Waititi's Star Wars Movie Won't Shoot This Year". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

External links

edit- Time Bandits at IMDb

- Time Bandits at AllMovie

- Time Bandits at the TCM Movie Database

- Time Bandits at Box Office Mojo

- Time Bandits at Rotten Tomatoes

- Time Bandits at the BFI's Screenonline

- "Time Bandits", an essay by Bruce Eder at the Criterion Collection