The Itneg (exonym "Tinguian" or "Tingguian") are an Austronesian indigenous peoples from the upland province of Abra and Nueva Era, Ilocos Norte in northwestern Luzon, Philippines.

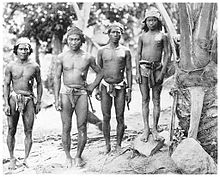

Tinguian men of Sallapadan. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 47,550[1] (2010) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Cordillera Administrative Region | |

| Languages | |

| Itneg, Ilocano, Tagalog | |

| Religion | |

| Animism (Indigenous Philippine folk religions), Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Episcopalianism, other Protestant sects) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Igorot people, Ilocano people |

Overview

editThe Itneg live in the mountainous area of Abra in northwestern Luzon who descended from immigrants from Kalinga, Apayao, and the Northern Kankana-ey. They refer to themselves as Itneg, though the Spanish called them Tingguian when they came to the Philippines because they are mountain dwellers. The Tingguians are further divided into nine distinct subgroups which are the Adasen, Mabaka, Gubang, Banao, Binongon, Danak, Moyodan, Dawangan, and Inlaud/Illaud.

History

editSpanish era migrations to Abra

editDuring pre-colonial times, the Itneg mostly lived near the coasts of Northern Luzon, where they interacted closely with the Ilocanos.[2] By the time the Spanish colonizers arrived, they had only a few inland settlements, but colonial pressures forced many of them to move inland during the sixteenth and senventeenth century.[2] Most of them settled in Abra, which then became the Itneg heartland.[2]

Discrimination during the Marcos dictatorship

editThe Itneg have faced ethnic discrimination and violence, with the era of Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos being a well-documented period of particular violence,[3] mostly linked to the infringement of the Marcos crony linked Cellophil Resources Corporation on forest resources in traditionally Itneg lands.[4]

Culture

editThe Tingguians still practice their traditional ways, including wet rice and swidden farming. Socio-cultural changes started when the Spanish conquistadors ventured to expand their reach to the settlements of Abra. The Spaniards brought with them their culture some of which the Tangguians borrowed. More changes in their culture took place with the coming of the Americans and the introduction of education and Catholic and Protestant proselytization.[5]

Social organization

editWealth and material possessions (such as Chinese jars, copper gongs called gangsa, beads, rice fields, and livestock) determine the social standing of a family or person, as well as the hosting of feasts and ceremonies. Despite the divide of social status, there is no sharp distinction between rich (baknang) and poor. Wealth is inherited but the society is open for social mobility of the citizens by virtue of hard work. Shamans are the only distinct group in their society, but even then it is only during ceremonial periods.[5]

The traditional leadership in the Tangguian community is held by panglakayen (old men), who compose a council of leaders representing each purok or settlement. The panglakayen are chosen for their wisdom and eagerness to protect the community's interest.[5] Justice is governed by custom (kadawyan) and trial by ordeal. Head-hunting was finally stopped through peace pacts (kalon).[5]

Marriage

editThe Itnegs’ marriage are arranged by the parents and are usually between distant relatives in order to keep the family close-knit and the family wealth within the kinship group. The parents select a bride for their son when he is six to eight years old, and the proposal is done to the parents of the girl. If accepted, the engagement is sealed by tying beads around the girl's waist as a sign of engagement. A bride price (pakalon) is also paid to the bride's family, with an initial payment and the rest during the actual wedding. No celebration accompanies the Itneg wedding and the guests leave right after the ceremony.[5]

Clothing

editThe women dress in a wrap-around skirt (tapis) that reaches to the knees and fastened by an elaborately decorated belt. They also wear short sleeved jacket on special occasions. The men, on the other hand, wear a G-string (ba-al) made of woven cloth (balibas). On special occasions, the men also wear a long-sleeved jacket (bado). They also wear a belt where they fasten their knife and a bamboo hat with a low, dome-shaped top. Beads are the primary adornment of the Tingguians and a sign of wealth.[5]

Housing

editThe Itneg people have two general types of housing. The first is a 2–3 room-dwelling surrounded by a porch and the other is a one-room house with a porch in front. Their houses are usually made of bamboo and cogon. A common feature of a Tingguian home with wooden floors is a corner with bamboo slats as flooring where mothers usually give birth. Spirit structures include balawa built during the say-ang ceremony, sangasang near the village entrance, and aligang containing jars of basi.[5]

Tattoos

editIn The Inhabitants of the Philippines (1900), the author describes two subgroups of the Banao people (itself a subgroup of the Itneg or "Tinguian" people), the Busao and the Burik people, as having elaborate tattoos, though he also notes that the custom was in the process of disappearing by the time he described them:[7][8]

"The Busao Igorrotes who live in the North of Lepanto, tattoo flowers on their arms, and in war-dress wear a cylindrical shako made of wood or plaited rattan, and large copper pendants on their ears. These people do not use the talibon, and prefer the spear. The Burik Igorrotes tattoo their body in a curious manner, giving them the appearance of wearing a coat of mail. But this custom is probably now becoming obsolete, for at least those of the Igorrotes who live near the Christian natives are gradually adopting their dress and customs."

— Frederic Henry Read Sawyer, The Inhabitants of the Philippines (1900), [7]

The hafted tools used by the Itneg were described as having a brush-like bundle of ten needles made of plant thorns attached to a handle made from a bent buffalo horn. The "ink" was made from soot obtained by burning a certain type of resinous wood.[8]

Most other groups of Itneg people were already being assimilated by Christianized lowlanders by the 19th century. Among these groups of Itneg, tattooing was not as prominent. Adult women usually tattooed their forearms with delicate patterns of blue lines, but these are usually covered up completely by the large amounts of beads and bracelets worn by women.[9] Some men tattoo small patterns on their arms and legs, which are the same patterns they use to brand their animals or mark their possessions. Warrior tattoos that indicate successful head-hunts were already extinct among the "civilized" Itneg, and warriors were not distinguished with special identifying marks or clothing from the general population.[9]

Cuisine

editRice is extensively grown by the Itneg. There are two types of practices for rice cultivation namely wet-rice cultivation and swidden/kaingin. Corn is also planted as a major subsistence and as a replacement for rice. Other products consumed are camote, yams, coconut, mango, banana and vegetables. Sugarcane is planted to make wine usually consumed during traditional rituals and ceremonies. Pigs and chickens are consumed for food or for religious rituals while carabaos are killed during large celebrations. Hunting wild animals and fishing is also prevalent. Eel and other freshwater fish such as paleleng and ladgo (lobster) are caught to make viands for most families.[5]

Weapons

editThe Tingguians use weapons for hunting, headhunting, and building a house, among others. Some examples of their weapons and implements are the lance or spear (pika), shield (kalasag), head axe (aliwa). Foremost among all these weapons and implements is the bolo which the Tangguians are rarely seen without.[5]

Language

editThe native Itneg language is a South-Central Cordilleran dialect continuum. The Itneg speak Ilocano as second language.

Indigenous Itneg religion

editThe Itnegs believe in the existence of numerous supernatural powerful beings. They believe in spirits and deities, the greatest of which they believe to be Kadaklan who lives up in the sky and who created the earth, the moon, the stars, and the sun. The Itnegs believe in life after death, which is in a place they call maglawa. They take special care to clean and adorn their dead to prepare them for the journey to maglawa. The corpse is placed in a death chair (sangadel) during the wake.[5]

Immortals

edit- Bagatulayan: the supreme deity who directs the activities of the world, including the celestial realms[10] referred also as the Great Anito[11]

- Gomayen: mother of Mabaca, Binongan, and Adasin[11]

- Mabaca: one of the three founders of the Tinguian's three ancient clans; daughter of Gomayen and the supreme deity[11]

- Binongan: one of the three founders of the Tinguian's three ancient clans; daughter of Gomayen and the supreme deity[11]

- Adasin: one of the three founders of the Tinguian's three ancient clans; daughter of Gomayen and the supreme deity[11]

- Emlang: servant of the supreme deity[11]

- Kadaklan: deity who is second in rank; taught the people how to pray, harvest their crops, ward off evil spirits, and overcome bad omens and cure sicknesses[12]

- Apadel (Kalagang): guardian deity and dweller of the spirit-stones called pinaing[13]

- Init-init: the god of the sun married to the mortal Aponibolinayen; during the day, he leaves his house to shine light on the world[14]

- Gaygayoma: the star goddess who lowered a basket from heaven to fetch the mortal Aponitolau, who she married[14]

- Bagbagak: father of Gaygayoma[14]

- Sinang: mother of Gaygayoma[14]

- Takyayen: child of Gaygayoma and Aponitolaul popped out between Gaygayoma's last two fingers after she asked Aponitolau to prick there[14]

- Makaboteng: the god and guardian of deer and wild hogs[15]

Mortals

editReferences

edit- ^ National Statistics Offiice (2013). 2010 Census of Population and Housing, Report No. 2A: Demographic and Housing Characteristics (Non-Sample Variables), Philippines (PDF) (Report). Manila. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Himes, R. S. (1997). Reconstructions in Kalinga-Itneg. Oceanic Linguistics, 36(1), 102–134. https://doi.org/10.2307/3623072

- ^ Pawilen, Reidan (4 May 2021). "The Solid North myth: An Investigation on the status of dissent and human rights during the Marcos Regime in Regions 1 and 2, 1969-1986". U.p. Los Baños Journal.

- ^ "Anti-Cellophil struggle: A continuing source of inspiration to IPs". 9 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sumeg-ang, Arsenio (2005). "9 The Tingguians/Itnegs". Ethnography of the Major Ethnolinguistic Groups in the Cordillera. Quezon City: New Day Publishers. pp. 177–194. ISBN 9789711011093.

- ^ Worcester, Dean C. (Oct 1906). "The Non-Christian Tribes of Northern Luzon". The Philippine Journal of Science. 1 (8): 791–875.

- ^ a b Sawyer, Frederic Henry Read (1900). The Inhabitants of the Philippines. New York: S. Low, Marston. p. 255.

- ^ a b Krutak, Lars (2017). "Burik: Tattoos of the Ibaloy Mummies of Benguet, North Luzon, Philippines". In Krutak, Lars; Deter-Wolf, Aaron (eds.). Ancient Ink: The Archaeology of Tattooing (First ed.). Seattle, Washington: University of Washington Press. pp. 37–55. ISBN 978-0-295-74282-3.

- ^ a b Cole, Fay-Cooper; Gale, Albert (1922). "The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe". Publications of the Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropology Series. 14 (2): 231–233, 235–489, 491–493.

- ^ Gaioni, D. T. (1985). The Tingyans of Northern Philippines and Their Spirit World. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft mbH.

- ^ a b c d e f Peraren, A. A. (1966). Tinguian Folklore and how it Mirrors Tinguian Culture and Folklife. University of San Carlos.

- ^ Millare, F. D. (1955). Philippine Studies Vol. 3, No. 4: The Tinguians and Their Old Form of Worship. Ateneo de Manila University.

- ^ Apostol, V. M. (2010). Way of the Ancient Healer: Sacred Teachings from the Philippine Ancestral Traditions. North Atlantic Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cole, M. C. (1916). Philippine Folk Tales . Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co.

- ^ Demetrio, F. R., Cordero-Fernando, G., & Zialcita, F. N. (1991). The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.