The Tongmenghui of China[a] was a secret society and underground resistance movement founded by Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren, and others in Tokyo, Empire of Japan, on 20 August 1905, with the goal of overthrowing China's Qing dynasty.[2][3] It was formed from the merger of multiple late-Qing dynasty Chinese revolutionary groups.

Tongmenghui of China 中國同盟會 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leader | Sun Yat-sen Song Jiaoren |

| Founded | 20 August 1905 |

| Dissolved | 25 August 1912 |

| Merger of | Xingzhonghui Huaxinghui Guangfuhui |

| Succeeded by | Kuomintang |

| Membership | c. 50,000–100,000 |

| Ideology | Chinese nationalism Han nationalism Republicanism Minsheng Anti-Qing sentiment Factions: Chinese anarchism[1] |

| Political position | Big tent |

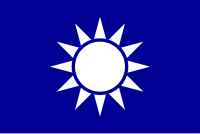

| Colours | Blue |

| Advisory Council (1909) | 5 / 200 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Tongmenghui | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 同盟會 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 同盟会 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

History

editRevolutionary era

editThe Tongmenghui was created through the unification of Sun Yat-sen's Xingzhonghui (Revive China Society), the Guangfuhui (Restoration Society) and many other Chinese revolutionary groups. Among the Tongmenghui's members were Huang Xing, Li Zongren, Zhang Binglin, Chen Tianhua, Wang Jingwei, Hu Hanmin, Tao Chengzhang, Cai Yuanpei, Li Shizeng, Zhang Renjie, and Qiu Jin.

In 1906, a branch of the Tongmenghui was formed in Singapore, following Sun's visit there; this was called the Nanyang branch and served as headquarters of the organization for Southeast Asia. The members of the branch included Wong Hong-kui (黃康衢; Huáng Kāngqú),[4][5] Tan Chor Lam (陳楚楠; Chén Chǔnán; 1884–1971)[citation needed] and Teo Eng Hock (張永福; Zhāng Yǒngfú; originally a rubber shoe manufacturer).[citation needed] Tan Chor Lam, Teo Eng Hock, and Chan Po-yin (陳步賢; Chén Bùxián; 1883–1965) started the revolution-related Chong Shing Chinese Daily Newspaper (中興日報; Zhōngxīng rìbào; 'China Revival Daily'),[citation needed] with the inaugural issue on 20 August 1907 and a daily distribution of 1,000 copies. The newspaper ended in 1910, presumably due to the Xinhai Revolution in 1911. Working with other Cantonese people, Tan, Teo, and Chan opened the revolution-related Kai Ming Bookstore (開明書報社; Kāimíng shūbàoshè; 'Opening wisdom bookstore')[6] in Singapore. For the revolution, Chan Po-yin raised over 30,000 yuan for the purchase and shipment (from Singapore to China) of military equipment and for the support of the expenses of people travelling from Singapore to China for revolutionary work.[7][page needed][8][unreliable source?]

From December 1906 to April 1908, seven Tongmenghui-led uprisings were defeated by the Qing government.[9]: 38 Numerous Tongmenghui members fled to southeast Asia.[9]: 38 There was an increase in discontent by the membership against Tongmenghui leadership.[9]: 38

In 1909, the headquarters of the Nanyang Tongmenghui was transferred to Penang. Sun Yat-Sen himself was based in Penang from July to December 1910. During this time, the 1910 Penang Conference was held to plan the Second Guangzhou Uprising. The high-powered Preparatory Meeting of Dr. Sun Yat Sen's supporters was subsequently held in Ipoh - at the villa of Teh Lay Seng, chairman of Tungmenghui Ipoh at Jalan Sungai Pari - to raise funds.[10] The Ipoh leaders were Teh Lay Seng, Wong I Ek, Lee Guan Swee and Lee Hau Cheong.[11] The leaders launched a major drive for donations across the Malay Peninsula. An amount of $47,683 Straits Settlement dollars was raised.[12] The Tongmenghui also started a newspaper, the Kwong Wah Jit Poh, with the first issue published in December 1910 from 120 Armenian Street, Penang.[citation needed]

In Henan, some Chinese Muslims were members of the Tongmenghui.[13]

Republican era

editAfter Shanghai was occupied by the revolutionaries in November 1911, the Tongmenghui moved its headquarters to Shanghai. After the Nanjing Provisional Government was established, the headquarters was moved to Nanjing. A general meeting was held in Nanjing on 20 January 1912, with thousands of members attending. Hu Hanmin, who represented the Provisional President Sun Yat-sen, moved that the Tongmenghui oath be changed to "overthrow the Manchu government, consolidate the Republic of China, and implement the Min Sheng Chu I". Wang Jingwei was elected as Chairman, succeeding Sun. Wang resigned the following month, and Sun resumed the chairmanship.[14][page needed]

After the establishment of the Republic of China, the Tongmenghui transformed itself into a political party on 3 March 1912, in preparation for participation in constitutional and parliamentary activities. It issued a Provisional Constitution of the Republic of China, which consisted of 34 articles, meaning it had 10 more than the constitutional proposal made when the Tongmenghui was a secret society. The leadership election was held on the same day, with Sun Yat-sen elected as Chairman, Huang Xing and Li Yuanhung as Vice-Chairmen. In May 1912, the Tongmenghui moved its headquarters to Beijing. At that time, the Tongmenghui was the largest party in China, with branches in Guangdong, Sichuan, Wuhan, Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Anqing, Fuzhou and Tianjin. It had a membership of about 550,000.[14][page needed] In August 1912, the Tongmenghui formed the nucleus of the Kuomintang, the governing political party of the republic.[citation needed]

Slogan and motto

editIn 1904, by combining republican, nationalist, and socialist objectives, the Tongmenghui came up with their political goal: to expel the Manchu rulers, to revive Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to distribute land equally among the people. (驅除韃虜, 恢復中華, 創立民國, 平均地權; Qūchú dálǔ, huīfù Zhōnghuá, chuànglì mínguó, píngjūn dì quán).[3] The Three Principles of the People were created around the time of the merging of Revive China Society and the Tongmenghui.[15][16]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Variously translated as Chinese United League, United League, Chinese Revolutionary Alliance, Chinese Alliance, United Allegiance Society, 中國同盟會; zhōngguó tóngménghuì.

References

edit- ^ Boorman (1968), p. 319.

- ^ "The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644–1911), Internal Threats". Countries Quest. Archived from the original on 16 September 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ a b 計秋楓; 朱慶葆 (2001). Zhongguo jin dai shi 中國近代史. Vol. 1. Chinese University Press. p. 468. ISBN 9789622019874.

- ^ "虎战. 驼峰险. 乱世情" [Tiger war. Hump danger. Troubled times.] (PDF). www.cnac.org (in Chinese).

- ^ 尤列事略补述一. ifeng.com (in Chinese). Phoenix New Media.

- ^ 张冬冬 (21 October 2011). (辛亥百年)探寻同德书报社百年坚守的"秘诀" [Xinhai Century: exploring the Tongmenhui publisher's hundred-year secret]. China News (in Chinese). Singapore. China News Service.

- ^ Chan Chung, Rebecca; Chung, Deborah; Ng Wong, Cecilia (2012). Piloted to Serve.[page needed]

- ^ "Piloted to Serve". Facebook.[unreliable source?]

- ^ a b c Yang, Zhiyi (2023). Poetry, History, Memory: Wang Jingwei and China in Dark Times. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-05650-7.

- ^ Chan, Sue Meng (2013). Road to Revolution: Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh. Singapore. Singapore: Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall. p. 17. ISBN 9789810782092.

- ^ Khoo & Lubis, Salma Nassution & Abdur-Razzaq (2005). Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development. Areca Books. p. 231.

- ^ Chan, Sue Meng (2013). Road to Revolution: Dr. Sun Yat Sen and His Comrades in Ipoh. Singapore: Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall. p. 10. ISBN 9789810782092.

- ^ Allès, Elisabeth (September–October 2003). "Notes on some joking relationships between Hui and Han villages in Henan". China Perspectives. 2003 (49). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.649.

- ^ a b Zhang, Yufa (1985). Minguo chu nian de zheng dang 民國初年的政黨. Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica.

- ^ Sharman, Lyon (1968). Sun Yat-sen: His life and its meaning, a critical biography. Stanford: Stanford University Press. pp. 94, 271.

- ^ Li Chien-Nung; Li Jiannong; Teng, Ssu-yu; Ingalls, Jeremy (1956). The political history of China, 1840–1928. Stanford University Press. pp. 203–206. ISBN 9780804706025.