The hundred man killing contest (百人斬り競争, hyakunin-giri kyōsō) was a newspaper account of a contest between Toshiaki Mukai (3 June 1912 – 28 January 1948) and Tsuyoshi Noda (1912 – 28 January 1948), two Japanese Army officers serving during the Japanese invasion of China, over who could kill 100 people the fastest while using a sword. The two officers were later executed on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity for their involvement.[1]

The news stories were rediscovered in the 1970s, which sparked a larger controversy over Japanese war crimes in China, particularly the Nanjing Massacre. The modern historical consensus is that the stories did not occur as they were described.[2][3] The original accounts printed in the newspaper described the killings as hand-to-hand combat; however, historians have suggested that they were most likely a part of Japanese mass killings of Chinese prisoners of war.[4][5]

Wartime accounts

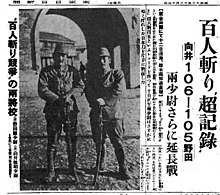

editIn 1937, the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun and its sister newspaper, the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, covered a contest between two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai (向井 敏明) and Tsuyoshi Noda (野田 毅), in which the two men were described as vying with one another to be the first to kill 100 people with a sword. The competition supposedly took place en route to Nanjing prior to the infamous Nanjing Massacre, and was covered in four articles from 30 November 1937, to 13 December 1937; the last two being translated in the Japan Advertiser.

Both officers supposedly surpassed their goal during the heat of battle, making it difficult to determine which officer had actually won the contest. Therefore, according to the journalists Asami Kazuo and Suzuki Jiro, writing in the Tokyo Nichi-Nichi Shimbun of 13 December, they decided to begin another contest with the goal of 150 kills.[6] The Nichi Nichi headline of the story of 13 December read "'Incredible Record' [in the Contest to] Behead 100 People—Mukai 106 – 105 Noda—Both 2nd Lieutenants Go Into Extra Innings".

Other soldiers and historians have noted the improbability of the lieutenants' alleged heroics, which entailed killing enemy after enemy in fierce hand-to-hand combat.[7] Noda himself, on returning to his hometown, admitted this during a speech that "I killed only four or five with sword in the real combat ... After we captured an enemy trench, we'd tell them, 'Ni Lai Lai.'[note 1] The Chinese soldiers were stupid enough to come out the trench toward us one after another. We'd line them up and cut them down from one end to the other."[8]

Trial and execution

editAfter the war, a written record of the contest found its way into the documents of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East. In 1947, the two soldiers were arrested by the U.S. Army and detained at Sugamo Prison. They were then extradited to China and tried by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal. On trial with the two men was Gunkichi Tanaka, a Japanese Army captain who personally killed over 300 Chinese POWs and civilians with his sword during the massacre. All three men were found guilty of atrocities committed during the Battle of Nanjing and the subsequent massacre, and sentenced to death. On 28 January 1948, the three were executed by shooting at a selected spot in the mountains of the Yuhuatai District. Mukai and Noda were both 35 years old; Tanaka was 42.[9][10]

Modern assessment

editIn Japan, the contest was lost to the obscurity of history until 1967, when Tomio Hora (a professor of history at Waseda University) published a 118-page document pertaining to the events of Nanjing. The story was unreported by the Japanese press until 1971, when Japanese journalist Katsuichi Honda brought the issue to the attention of the public with a series of articles written for Asahi Shimbun, which focused on interviews with Chinese survivors of the World War II occupation and massacres.[11]

In Japan, the articles sparked fierce debate about the Nanjing Massacre, with the veracity of the killing contest a particularly contentious point of debate.[12] Over the following years, many authors have argued over whether the Nanjing Massacre even occurred, with viewpoints on the subject also being a predictor for whether they believed the contest was a fabrication.[13] The Sankei Shimbun and Japanese politician Tomomi Inada have publicly demanded that the Asahi and Mainichi media companies retract their wartime reporting of the contest.[14]

In a later work, Katsuichi Honda placed the account of the killing contest into the context of its effect on Imperial Japanese forces in China. In one instance, Honda notes Japanese veteran Shintaro Uno's autobiographical description of the effect on his sword after consecutively beheading nine prisoners.[15] Uno compares his experiences with those of the two lieutenants from the killing contest.[15] Although he had believed the inspirational tales of hand-to-hand combat in his youth, after his own experience in the war, he came to believe the killings were more likely brutal executions.[15] Uno adds,

Whatever you say, it's silly to argue about whether it happened this way or that way when the situation is clear. There were hundreds of thousands of soldiers like Mukai and Noda, including me, during those fifty years of war between Japan and China. At any rate, it was nothing more than a commonplace occurrence during the so-called Chinese Disturbance.[15]

In 2000, Bob Wakabayashi weighed in with his own study which concluded that although "the killing contest itself was a fabrication" by journalists, it "provoked a full-blown controversy as to the historicity of the Nanking Atrocity as a whole." In turn, the controversy "increased the Japanese people's knowledge of the Atrocity and raised their awareness of being victimizers in a war of imperialist aggression despite efforts to the contrary by conservative revisionists."[3] In a later book, Wakabayashi quotes Joshua Fogel as saying that "to accept the story as true and accurate requires a leap of faith that no balanced historian can make."[16]

The Nanjing Massacre Memorial in China includes a display on the contest among its many exhibits. A Japan Times article has suggested that its presence allows revisionists to "sow seeds of doubt" about the accuracy of the entire collection.[17]

The contest is depicted in the 1994 film Black Sun: The Nanking Massacre, as well as the 2009 film, John Rabe.[citation needed]

In April 2003, the families of Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda filed a defamation suit against Katsuichi Honda, Kashiwa Shobō, the Asahi Shimbun, and the Mainichi Shimbun, requesting ¥36,000,000 in compensation, and for Honda's publications to be retracted due to "inveracity". On 23 August 2005, Tokyo District Court Judge Akio Doi ruled against the plaintiffs. The court argued that as both soldiers were deceased, discussions over their wartime behavior do not infringe on their "honor and privacy rights". Instead, it could be claimed that a false narrative infringed on the plaintiffs' "affection for and admiration for the two lieutenants", but the court dismissed this claim as well. The judge noted that "the contents of the news article are ... extremely questionable" but that second-hand discussions of the news story do not constitute slander; instead, it has become part of a historical discussion wherein "the evaluation as a historical fact is still in the undetermined situation."[18][19] Some evidence of killing Chinese POWs (not hand-to-hand fighting) was shown by the defendants, and the court supported the possibility that the "contestants" killed POWs by sword, which in its view would suggest that the story is not "completely false in an important part".[18] In December 2006, the Supreme Court of Japan upheld the decision of the Tokyo District Court.[20]

See also

editNotes

editReferences

editCitations

edit- ^ Takashi Yoshida. The making of the "Rape of Nanking". 2006, p. 64.

- ^ Fogel, Joshua A. The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography. 2000, p. 82.

- ^ a b Wakabayashi 2000, p. 307.

- ^ Honda 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Kajimoto 2015, Postwar Judgment: II. Nanking War Crimes Tribunal.

- ^ Wakabayashi 2000, p. 319.

- ^ Kajimoto 2015, p. 37, Postwar Judgment: II. Nanking War Crimes Tribunal.

- ^ Honda 1999, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Nanta, Arnaud (13 May 2021), Cheng, Anne; Kumar, Sanchit (eds.), "Historiography of the Nanking Massacre (1937–1938) in Japan and the People's Republic of China: evolution and characteristics", Historians of Asia on Political Violence, Institut des civilisations, Paris: Collège de France, ISBN 978-2-7226-0575-6, retrieved 11 March 2022

- ^ Sheng, Zhang (8 November 2021). The Rape of Nanking: A Historical Study. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-065289-5.

- ^ Honda 1999, p. ix.

- ^ Fogel, Joshua A. The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography. 2000, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Honda 1999, pp. 126–127, Footnote.

- ^ Schreiber, Mark, "U.S. sea patrols fuel war of words in print Archived 2015-11-02 at the Wayback Machine", Japan Times, 1 November 2015, p. 18

- ^ a b c d Katsuichi Honda, ed. Frank Gibney. The Nanjing massacre: a Japanese journalist confronts Japan's national shame. 1999, pp. 131–132, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0765603357

- ^ Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, The Nanking Atrocity 1937–1938 (Berghahn Books, 2007), p. 280.

- ^ Kingston 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b Hogg, Chris (23 August 2005). "Victory for Japan's war critics". BBC News. Archived from the original on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- ^ Heneroty 2005.

- ^ 国の名誉守りたい 稲田衆院議員 「百人斬り裁判」を本に [Congressman Inada published the incidents regarding the court on the hundred man killing contest]. Fukui Shimbun. 17 May 2007. Archived from the original on 6 August 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2013 – via 47NEWS.

Bibliography

edit- Kingston, Jeff (10 August 2008), "War and reconciliation: a tale of two countries", Japan Times, p. 9, archived from the original on 5 October 2016, retrieved 1 May 2017.

- Powell, John B. (1945), My Twenty-five Years in China, New York: Macmillan, pp. 305–308.

- Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi (Summer 2000), "The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt Amid Fabricated Illusions, 1971–75", Journal of Japanese Studies, 26 (2), The Society for Japanese Studies: 307–340, doi:10.2307/133271, ISSN 0095-6848, JSTOR 133271

- Honda, Katsuichi (1999) [Main text from Nankin e no Michi (The Road to Nanjing), 1987.], Gibney, Frank (ed.), The Nanjing Massacre: A Japanese Journalist Confronts Japan's National Shame, M. E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-7656-0335-7, retrieved 24 February 2010

- Kajimoto, Masato (July 2015), The Nanking Massacre: Nanking War Crimes Tribunal, Graduate School of Journalism of the University of Missouri-Columbia, 172, archived from the original on 13 July 2015, retrieved 4 August 2016,

However, as many historians point out today, the stories of hyped heroism, in which those soldiers courageously killed a number of enemies in hand-to-hand combat with swords, couldn't be taken at face value. ... The three researchers interviewed by author for this project, Daqing Yang, Ikuhiko Hata, and Akira Fujiwara said that the contest could have been mere mass murder of prisoners.

- Heneroty, Kate (23 August 2005), "Japanese court rules newspaper didn't fabricate 1937 Chinese killing game", Paper Chase, University of Pittsburgh: JURIST Legal News and Research Services, archived from the original on 25 February 2011, retrieved 24 February 2010

Further reading

edit- In English

- In Japanese

- Full text of all articles pertaining to the event

- 百人斬り訴訟で東京地裁は遺族の敗訴だが朝日新聞記事と東京日日新聞記事は違う点を無視の報道

- Decision of the Tokyo District Court (full text)

- Mochizuki's Memories "Watashi no Shina-jihen" (私の支那事変), one of the exhibits in evidence at the Tokyo District Court, which revealed Noda and Mukai beheaded Chinese farmers with their swords during the killing contest.