Tougaloo College is a private historically black college in the Tougaloo area of Jackson, Mississippi, United States. It is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ). It was established in 1869 by New York–based Christian missionaries for the education of freed slaves and their offspring. From 1871 until 1892 the college served as a teachers' training school funded by the state of Mississippi. In 1998, the buildings of the old campus were added to the National Register of Historic Places. Tougaloo College has an extensive history of civic and social activism, including the Tougaloo Nine.

Tougaloo College seal | |

Former names | Tougaloo University (1871–1916) |

|---|---|

| Motto | "Where History Meets the Future" |

| Type | Private historically black college |

| Established | 1869 |

| Affiliation | UNCF |

Religious affiliation | United Church of Christ and Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) |

| Endowment | $10 million |

| President | Donzell Lee (interim) |

Academic staff | 100 |

| Undergraduates | 650 |

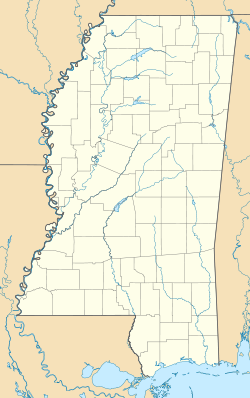

| Location | , U.S. 32°24′11″N 90°09′39″W / 32.40306°N 90.16083°W |

| Colors | Royal Blue & Scarlet |

| Nickname | Bulldogs and Lady Bulldogs |

Sporting affiliations | NAIA – HBCUAC |

| Website | www |

| |

Tougaloo College | |

Strieby Hall in 1899 | |

| Location | Tougaloo, Mississippi |

| Area | 15 acres (6.1 ha) |

| Built | 1848 |

| NRHP reference No. | 98001109[1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 31, 1998 |

History

editEstablishment

editIn 1869, the American Missionary Association of New York purchased 500 acres (202 ha) of one of the largest former plantations in central Mississippi to build a college for freedmen and their children, recently freed slaves. The purchase included a standing mansion and outbuildings, which were immediately converted for use as a school.[2] The next year expansion of facilities began in earnest with the construction of two new buildings—Washington Hall, a 70-foot-long edifice containing classrooms and a lecture hall, and Boarding Hall, a two-story building which included a kitchen and dining hall, a laundry, and dormitories for 30 female students.[2]

Costs of construction were paid by the United States government through the education department of its Bureau of Refugees and Freedmen.[2] Additional funds, totaling $25,500 in all, were provided for development of the school farm, including monies for farm implements and livestock.[2]

In 1871, the Mississippi State Legislature granted the new institution a formal charter under the name of Tougaloo University. No contingency fund was provided for the day-to-day operation of the school, with some students paying a tuition of $1 per month while others attended tuition free, contributing labor on the school farm in lieu of fees.[2] The cost of two teachers at the school for five months were paid by the county boards of education of Hinds and Madison Counties; all additional operating funds were provided by the American Missionary Association.[2]

In its initial institutional form, Tougaloo University was not a university but provided basic education for black students born under slavery. Another goal was to train African-American students for service as teachers. At the end of 1871, the school included 94 "elementary students", 47 that were part of the "normal school", and one categorized as "academic" (college preparaatory)—a total student body of 142.[3] At this time the school found itself in dire need of expanded facilities and operational funds; an appeal was made by three leaders of Tougaloo University to the Mississippi Superintendent of Public Education for a state role in the institution.[3] Legislation followed authorizing the establishment of a State Normal School on the grounds of Tougaloo and providing a total of $4,000 for two years to help provide teachers' salaries, student aid, and for the purchase of desks.[3]

As part of the establishment of the Normal School at Tougaloo, each county in the state was provided with two free scholarships, and every student declaring an intention to teach in Mississippi's common schools was to be allotted a stipend of 50 cents per week out of the state funds for student aid, an amount capped at $1,000 per year.[4]

In 1873, Tougaloo University added a theological department for students intending on entering the Christian ministry and expanded its industrial department, adding a cotton gin, apparatus for grinding corn, and developing capacity for the manufacture of simple furniture on site.[4]

On January 23, 1881, Washington Hall—the main classroom building—caught fire during religious services and was entirely destroyed.[5] For the rest of the academic year, classes were conducted in a new barn recently constructed on campus, nicknamed "Ayrshire Hall".[5] On May 31, 1881, the foundation was laid for a new classroom building, a three-storey facility named Strieby Hall after M.E. Strieby of New York, a venerated leader of the American Missionary Association.[5]

Courses for college credit were first offered in 1897, and the first Bachelor of Arts degree was awarded in 1901.[citation needed]

In 1916, the name of the institution was changed to Tougaloo College.

Return to private status

editTougaloo remained predominantly a teacher training school until 1920 when the college ceased receiving aid from the state.

Mergers

editSix years after Tougaloo's founding, the Home Missionary Society of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) obtained a charter from the Mississippi State Legislature to establish a school at Edwards, Mississippi, to be known as Southern Christian Institute. That same year, Sarah Ann Dickey, who had worked with the American Missionary Association since the 1860s, established the Mount Hermon Female Seminary, which would later merge with Tougaloo in 1924,[6] as the two schools had similar ideals and goals. Similarly, the Southern Christian Institute would merge with Tougaloo in 1954.

Recent history

editCarmen J. Walters, the fourteenth president (and second female president), began her tenure July 1, 2019. She stepped down in June 2023 and Donzell Lee was appointed interim president.[7]

In 2020, Tougaloo received $6 million (~$6.96 million in 2023) from philanthropist MacKenzie Scott. It is the largest gift from a single donor in Tougaloo's history.[8]

Presidents

edit- Ebenezer Tucker (from 1869–1870, as principal)[9][10]

- Andrew J. Steele (from 1870–1873, as principal)[9]

- John K. Nutting (from 1873–1875, as principal/president)[9]

- Leander A. Darling (from 1875–1877, as principal/president)

- George S. Pope (from 1877–1887)

- Frank G. Woodworth (from 1887–1912)

- William T. Holmes (from 1913–1933)

- Charles B. Austin (from 1933–1935, as acting)

- Judson L. Cross (from 1935–1945)

- Lionel B. Fraser (from 1945–1947, as acting)

- Harold C. Warren (from 1947–1955)

- Addison A. Branch (from 1955–1956, as acting)

- Samuel C. Kincheloe (from 1956–1960)[11]

- Adam Daniel Beittel (from 1960–1964)[12]

- George Albert Owens (from 1964–1965, as acting)[12]

- George Albert Owens (from 1965–1984)[12]

- J. Herman Blake (from 1984–1987)[13]

- Charles A. Baldwin (from 1987–1988, as acting)[14]

- Adib A. Shakir (from 1988–1994)[15]

- Edgar E. Smith (from 1994–1995, as acting)

- Joseph A. Lee (from 1995–2001)[16]

- James H. Wyche (from 2001–2002, as acting)[17]

- Beverly W. Hogan (from 2002–2019)[18]

- Carmen J. Walters (from 2019–2023)[19]

- Donzell Lee (from 2023–present, as acting)[20]

Campus

editThe campus is in Jackson,[21] and in Madison County.[22] The campus includes a Historic District, which comprises ten buildings that are each listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Robert O. Wilder Building, built in 1860 and also known as "The Mansion", overlooks the ensemble of buildings forming the college's historic core.

Woodworth Chapel, originally known as Woodworth Church, was built in 1901 by students. It was restored and rededicated in 2002. In September 2004, the National Trust for Historic Preservation awarded Tougaloo College the National Preservation Honor Award for the restoration of Woodworth Chapel. The restoration was also recognized by the Mississippi Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, who bestowed its Honor Award. Woodworth Chapel houses the Union Church, founded alongside the college as a Congregational Church. Today, it is one of two congregations of the United Church of Christ in Mississippi. Located in the heart of the campus beside Woodworth Chapel is Brownlee Gymnasium. Built in 1947, the building was named in honor of Fred L. Brownlee, former general secretary of the American Missionary Association.

The college holds the prestigious Tougaloo Art Collection. It was begun in 1963, by a group of prominent New York artists, curators and critics, initiated by the late Ronald Schnell, Professor Emeritus of Art, as a mechanism to motivate his art students. The collection consists of pieces by African American, American and European artists. Included in the African-American portion of the collection are pieces by notable artists Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, David Driskell, Richard Hunt, Elizabeth Catlett and Hale Woodruff. The 1,150 works in the Tougaloo Art Collection include paintings, sculptures, drawings, collages, various forms of graphic art and ornamental pieces.

The Tougaloo Art Colony is another distinctive resource of the college. Begun in 1997 under the leadership of former College trustee, Jane Hearn, the Tougaloo Art Colony affords its participants exposure to and intensive instruction by artists. The Civil Rights Library and Archives are a part of Tougaloo College. Among their holdings are the original papers, photographs and memorabilia of movement leaders including Fannie Lou Hamer, Medgar Evers and Martin Luther King Jr. It contains the works of blues musician B.B. King.

The college established the Medgar Evers Museum in 1996. The Evers family (trustee Myrlie Evers-Williams and her children with Medgar) donated their home to Tougaloo College for its historical significance. In 1996, the home was restored to its condition at the time of Mr. Evers' assassination in the driveway. It is operated as a house museum and is open to the public. In 2020, the home was acquired by the National Park Service and designated a national monument.[23]

Academics

editAccording to the Tougaloo College website, "over 40% of the African American physicians and dentists practicing in the state of Mississippi, more than one-third of the state's African American attorneys and educators including teachers, principals, school superintendents, college/university faculty and administrators" were trained at the school.[24]

In the 2022 U.S. News & World Report college and university rankings, Tougaloo College ranked #15 among historically black colleges and universities.[25] The same magazine reported that in 2022 only 18% of the college's students graduated after four years, placing Tougaloo at the bottom of national rankings.[26]

Tougaloo College is accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS); the college was initially accredited by SACS in 1953.[27] As of 2012, it is in good standing with SACS.[28]

Athletics

editThe Tougaloo athletic teams are called the Bulldogs. The college is a member of the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA), primarily competing in the HBCU Athletic Conference (HBCUAC), formerly the Gulf Coast Athletic Conference (GCAC), since the 1981–82 academic year.

Tougaloo competes in 11 intercollegiate varsity sports: Men's sports include baseball, basketball, cross country, soccer and tennis; women's sports include basketball, competitive cheer, cross country, soccer, tennis and volleyball.

Notable people

editFaculty

edit- Ernst Borinski (1901–1983), sociologist[29]

- L. Zenobia Coleman (1898–1999), librarian[30]

- James W. Loewen (1942–2021), author[31]

- John U. Monro (1912–2002), director of the writing center[32][33]

Alumni

edit| Name | Class year | Notability | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reuben V. Anderson | 1965 | first black judge to sit on the Mississippi Supreme Court | [34] |

| Edward Blackmon, Jr. | 1971 | Mississippi House of Representatives | [35] |

| Colia Clark | civil rights activist and candidate for U.S. Senate in New York | ||

| Aunjanue Ellis | attended | actor | |

| Slayton A. Evans, Jr. | 1965 | research chemist and professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill | [36] |

| Constance Slaughter-Harvey | 1967 | first black judge in the state of Mississippi | [37][38] |

| Lawrence Guyot | 1963 | civil rights activist who was director of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party | [39] |

| Beverly Wade Hogan | 1973 | mental health advocate, first female president of Tougaloo College | [40] |

| Joyce Ladner | 1964 | sociologist, civil rights activist, and first female president of Howard University | [41] |

| Anne Moody | 1964 | author and civil rights activist | [42] |

| Joan Trumpauer Mulholland | 1964 | civil rights activist and first white student | [43] |

| Hakeem Oluseyi | 1991 | astrophysicist and popularizer of science | [44][45] |

| Aaron Shirley | 1955 | founder of Jackson Medical Mall and recipient of MacArthur award | [46] |

| Arthur Tate | first African American to serve in the Mississippi State Senate since the Reconstruction era | ||

| Bennie Thompson | 1968 | U.S. Congressman | [47] |

| Walter Turnbull, PhD | 1966 | founder of the Boys Choir of Harlem | [48] |

| Walter Washington | former General President of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity and President of Alcorn State University | ||

| Karen Williams Weaver | 1982 | Mayor, city of Flint, Michigan | [49] |

| Charles Young Jr. | Mississippi House of Representatives | [50] | |

| Tommie Mabry | 2011 | Author and Advocate for Impoverished youth | [51] |

References

edit- ^ "National Register Information System – (#98001109)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Edward Mayes, History of Education in Mississippi. United States Bureau of Education Circular of Information No. 2, 1889. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1899; p. 259.

- ^ a b c Mayes, History of Education in Mississippi, p. 260.

- ^ a b Mays, History of Education in Mississippi, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Mayes, History of Education in Mississippi, p. 263.

- ^ Butchart, Ronald E. (2002). "Mission Matters: Mount Holyoke, Oberlin, and the Schooling of Southern Blacks, 1861-1917". History of Education Quarterly. 42 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5959.2002.tb00098.x. ISSN 0018-2680. JSTOR 3218165. S2CID 144813001.

- ^ Minta, Molly (June 6, 2023). "Yet another college president steps down, this time at Tougaloo". Mississippi Today. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ^ "Tougaloo College Receives $6 Million Gift from Philanthropist Mackenzie Scott". December 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Encore. Encore Communications, Incorporated. 1973. p. 46.

- ^ Holtzclaw, R. Fulton (1984). Black Magnolias: A Brief History of the Afro-Mississippian, 1865-1980. Keeble Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-933144-06-4.

- ^ "Tougaloo College Plans To Install President". Clarion-Ledger. October 9, 1956 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Shugana, Williams (July 11, 2017). "Tougaloo College". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Center for Study of Southern Culture. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "J. Herman Blake Wins the Distinguished Career Award from the American Sociology Association". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. August 13, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "Tougaloo College hopes to raise $1 million". WAPT. April 21, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "B-CC Vice President May Move On". Orlando Sentinel. January 5, 1988. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "Joseph A. Lee honored as first African American". Knoxville News Sentinel. November 17, 2019. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "Tougaloo Is a 'Natural Fit' for New Interim President". Diverse: Issues In Higher Education. October 10, 2001. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Wright, Aallyah (March 19, 2019). "Tougaloo names Dr. Carmen J. Walters 14th president; alumni express concerns". Mississippi Today. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ Watkins, Billy (March 18, 2019). "New Orleans native named head of Tougaloo College in Mississippi". NOLA.com. Retrieved May 12, 2023.

- ^ "Office of the President | Tougaloo College".

- ^ "Home". Tougaloo College. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

500 West County Line Road • Tougaloo, MS 39174

- Compare with the city and county maps.

Campus map: "Proposed Parking Plan" (PDF). Tougaloo College. Retrieved June 30, 2021.

Compare with a 2020 U.S. Census map of Jackson: "2010 CENSUS - CENSUS BLOCK MAP: Jackson city, MS (page 3)" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved June 30, 2021. - 2020 map indicates the same on page 3 (PDF p. 4/13). - ^ "Tougaloo College". USGS. Retrieved July 1, 2021. - The entry states it is in Madison County.

Compare with a map of Madison County: "General Highway Map of Madison County, Mississippi" (PDF). Mississippi State Highway Department. 1987. Retrieved June 30, 2021. - Also seen in the 2020 US Census entry for Madison County, page 15 (PDF p. 16/21) - ^ "Medgar and Myrlie Evers Home Officially Established As National Monument | Delta Democrat-Times". www.ddtonline.com. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ Tougaloo College QuickFacts, Tougaloo College (last accessed November 4, 2018).

- ^ "Tougaloo College - Profile, Rankings and Data". US News Best Colleges. March 10, 2016. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ "Tougaloo College". US News and World Report.

- ^ Accredited and Candidate List Includes Commission Actions taken 06/2018 Archived July 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, June 2018, Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

- ^ Scott Jaschik, Saint Paul's Loses Accreditation, Inside Higher Ed (June 22, 2012).

- ^ Buck, Henrietta (May 28, 1983). "Civil rights activist Borinski dies". Clarion-Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

Recognized as an influential force in the quest for civil rights during the 1950s and early 1960s, he was instrumental in initiating academic forums in the state to increase awareness of civil injustices.

- ^ Thomas, Melanie R. Coleman, L. Zenobia (21 Jan. 1898–3 May 1999). Oxford African American Studies Center. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195301731.013.38284. ISBN 978-0-19-530173-1. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Italie, Hillel (August 21, 2021). "James W. Loewen, wrote 'Lies My Teacher Told Me,' dead at 79". Associated Press. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ Capossela, Toni-Lee (April 15, 2013). "Vita: John Usher Monro". Harvard Magazine. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Severo, Richard (April 3, 2002). "John U. Monro, 89, Dies; Left Harvard to Follow Ideals". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Hillinger, Charles (March 27, 1988). "A Jurist With a Long Career of Firsts: Anderson 1st Black to Sit on Mississippi High Court". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. pp. A-9, B-9.

- ^ Carey Jr., Charles W. (2008). "Evans, Slaton A., Jr.". African Americans in Science: An Encyclopedia of People and Progress. ABC-CLIO. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-1-85109-999-3.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. pp. A-86, B-7.

- ^ "First black judge of Miss. to speak at Alcorn diversity event". April 19, 2013. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. pp. A-37, B-6.

- ^ "Beverly Wade Hogan". Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "From Swastika to Jim Crow". PBS.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. p. B-6.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. pp. A-70, B-6.

- ^ "Faculty and Staff Profiles". Florida Institute of Technology.

- ^ Hakeem, Oluseyi. "personal profile". LinkedIn. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. p. B-3.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. pp. A-94, B-8.

- ^ 2020 Tougaloo College Alumni Directory. Dallas, Texas: PCI. 2021. p. B-7.

- ^ "Mayor Dr. Karen Weaver". City of Flint, Michigan. City of Flint (MI). Archived from the original on October 8, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

graduated with her bachelor's degree in psychology from Tougaloo College, in Tougaloo, Mississippi.

- ^ "Charles Young, Jr". Mississippi House of Representatives. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ "Tommie Mabry". PBS. Retrieved February 17, 2024.