Utagawa Toyoharu (歌川 豊春, c. 1735 – 1814) was a Japanese artist in the ukiyo-e genre, known as the founder of the Utagawa school and for his uki-e pictures that incorporated Western-style geometrical perspective to create a sense of depth.

Born in Toyooka in Tajima Province,[1] Toyoharu first studied art in Kyoto, then in Edo (modern Tokyo), where from 1768 he began to produce designs for ukiyo-e woodblock prints. He soon became known for his uki-e "floating pictures" of landscapes and famous sites, as well as copies of Western and Chinese perspective prints. Though his were not the first perspective prints in ukiyo-e, they were the first to appear as full-colour nishiki-e, and they demonstrate a much greater mastery of perspective techniques than the works of his predecessors. Toyoharu was the first to make the landscape a subject of ukiyo-e art, rather than just a background to figures and events. By the 1780s he had turned primarily to painting. The Utagawa school of art grew to dominate ukiyo-e in the 19th century with artists such as Utamaro, Hiroshige, and Kuniyoshi.

Life and career

editUtagawa Toyoharu was born c. 1735[a] in Toyooka in Tajima Province. He studied in Kyoto under Tsuruzawa Tangei of the Kanō school of painting. It may have been around 1763 that he moved to Edo (modern Tokyo), where he studied under Toriyama Sekien. The Toyo (豊) in the art name Toyoharu (豊春) is said to have come from Sekien's personal name Toyofusa (豊房).[3] Some sources hold he also studied under Ishikawa Toyonobu and Nishimura Shigenaga.[4] Other art names Toyoharu went under include Ichiryūsai (一竜斎 ), Senryūsai (潜竜斎), and Shōjirō (松爾楼). Tradition holds that the name Utagawa derives from Udagawa-chō, where Toyoharu lived in the Shiba district in Edo.[3] His common name was Tajimaya Shōjirō (但馬屋 庄次郎), and he also used the personal names Masaki (昌樹) and Shin'emon (新右衛門).[4]

Toyoharu's work began to appear about 1768.[3] His earliest work includes woodblock prints in a refined, delicate style of beauties and actors.[4] Soon he began to produce uki-e "floating picture" perspective prints, a genre in which Toyoharu applied Western-style one-point perspective to create a realistic sense of depth. Most were of famous sites, including theatres, temples, and teahouses.[3] Toyoharu's were not the first uki-e—Okumura Masanobu had made such works since the early 1740s, and claimed the genre's origin for himself.[5] Toyoharu's were the first uki-e in the full-colour nishiki-e genre that had developed in the 1760s.[6][7] Several of his prints were based on imported prints from the West or China.[8]

From the 1780s Toyoharu appears to have dedicated himself to painting, and also produced kabuki programs and billboards after 1785.[9] He headed the painters involved in the restoration of Nikkō Tōshō-gū in 1796.[3] He died in 1814 and was buried in Honkyōji Temple in Ikebukuro under the Buddhist posthumous name Utagawa-in Toyoharu Nichiyō Shinji (歌川院豊春日要居士).[b][11]

- Western influence on Toyoharu

-

The Canal Grande from Santa Croce to the East

Canaletto, oil on canvas, 18th century -

The Canal Grande from Santa Croce to the East

Antonio Visentini, copperplate engraving, 1742 -

The Bell which Resounds for Ten Thousand Leagues in the Dutch Port of Frankai

Toyoharu, woodblock print, c. 1770s

Style

editHarunobu, c. 1760s

Toyoharu's works have a gentle, calm, and unpretentious touch,[4] and display the influence of ukiyo-e masters such as Ishikawa Toyonobu and Suzuki Harunobu.[3] Harunobu pioneered the full-colour nishiki-e print[12] and was particularly popular and influential in the 1760s, when Toyoharu first began his career.[13]

Toyoharu produced a number of willowy, graceful bijin-ga portraits of beauties in hashira-e pillar prints.[4] Only about fifteen examples of his bijin-ga are known, almost all from his earliest period.[14] One of the better-known examples of Toyoharu's work in this style is a four-sheet set depicting the Chinese ideal of the four arts.[4] Toyoharu produced a small number of yakusha-e actor prints that, in contrast to the works of the leading Katsukawa school, are executed in the learned style of an Ippitsusai Bunchō.[4]

While Toyoharu trained in Kyoto he may have been exposed to the works of Maruyama Ōkyo, whose popular megane-e were pictures in one-point perspective meant to be viewed in a special box in the manner of the French vue d'optique.[15] Toyoharu may also have seen the Chinese vue d'optique prints made in the 1750s that inspired Ōkyo's work.[16]

Early in his career, Toyoharu began producing the uki-e for which he is best remembered. Books on geometrical perspective translated from Dutch and Chinese sources appeared in the 1730s, and soon after, ukiyo-e prints displaying these techniques appeared first in the works of Torii Kiyotada and then of Okumura Masanobu. These early examples were inconsistent in their application of perspective techniques, and the results can be unconvincing; Toyoharu's were much more dextrous,[17] though not strict—he manipulated it to allow the representation of figures and objects that otherwise would have been obscured.[18] Toyoharu's works helped pioneer the landscape as an ukiyo-e subject, rather than merely a background for human figures[19] or events, as in Masanobu's works.[20] Toyoharu's earliest uki-e cannot be reliably dated, but are assumed to have appeared before 1772: early in that year[c] the Great Meiwa Fire in Edo destroyed the Niō-mon gate in Ueno, the subject of Toyoharu's Famous Views of Edo: Niō-mon in Ueno.[d][10]

Several of Toyoharu's prints were imitations of imported prints of famed European locations, some of which were Western and others Chinese imitations of Western prints. The titles were often fictional: The Bell which Resounds for Ten Thousand Leagues in the Dutch Port of Frankai is an imitation of a print of the Grand Canal of Venice from 1742 by Antonio Visentini, itself based on a painting by Canaletto.[8] Toyoharu titled another A Perspective View of French Churches in Holland, though he based it on a print of the Roman Forum.[21] Toyoharu took licence with other details of foreign lands, such as having the Dutch swim in their canals.[12] Japanese and Chinese mythology were also frequent subjects in Toyoharu's uki-e prints, the foreign perspective technique giving such prints an exotic feel.[22]

In his nikuhitsu-ga paintings the influence of Toyonobu can seem strong, but in his seals on these paintings Toyoharu proclaims himself a pupil of Sekien.[4][e] His efforts contributed to the development of the Rinpa school.[3] His paintings have joined the collections of foreign museums such as the British Museum, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Freer Gallery of Art. His paintings include byōbu folding screens—a genre in which ukiyo-e is said to have its origins, but was rare in ukiyo-e after the development of nishiki-e prints. A six-panel example of a spring scene in Yoshiwara[f] resides in France[23] in a private collection.[24]

- The Four Arts by Toyoharu

-

Shamisen

-

Painting

-

Calligraphy

-

Playing Go

- Perspective prints by Toyoharu

-

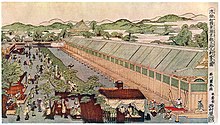

From the seventh act of the Kanadehon Chūshingura, c. 1770s

-

Perspective View of the Theatres in Sakai-chō and Fukiya-chō on Opening Night, c. 1770s

-

Momotarō and his Animal Friends Conquer the Demons, c. 1770s

Legacy

editThe popularity of Toyoharu's work peaked in the 1770s.[8] By the 19th century, Western-style perspective techniques had ceased to be a novelty and had been absorbed into Japanese artistic culture, deployed by such artists as Hokusai and Hiroshige,[25] two artists best remembered for their landscapes, a genre Toyoharu pioneered.[26]

The Utagawa school that Toyoharu founded was to become one of the most influential,[27] and produced works in a far greater variety of genres than any other school.[28] His students included Toyokuni and Toyohiro;[3] Toyohiro worked in the style of his master, while Toyokuni,[29] who headed the school from 1814,[26] became a prominent and prolific producer of yakusha-e prints of kabuki actors.[29] Other well-known members of the school were Utamaro, Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisada.[27] Though Japanese art schools, such as the Katsukawa in ukiyo-e and the Kanō in painting, emphasized a uniformity of style, a general style in the Utagawa school is not easy to recognize aside from a concern with realism and facial expressiveness.[28] The school dominated ukiyo-e production by the mid-19th century, and most of the artists—such as Kobayashi Kiyochika—who documented the modernization of Japan during the Meiji period during ukiyo-e's declining years belonged to the Utagawa school.[30]

The Torii school lasted longer, but the Utagawa school had more adherents. It fostered closer master–student relations and more systematized training than in other schools. Excepting a few prominent examples, such as Hiroshige or Kuniyoshi, the later generations of artists tended to lack stylistic diversity, and their work has become emblematic of ukiyo-e's decline in the 19th century.[13]

Toyoharu also taught painting. His most prominent student was Sakai Hōitsu.[3]

As of 2014, studies into Toyoharu's work have not been carried out in depth. Cataloguing and analyzing his work and his and his publishers' seals was still in its infancy.[31] However, his work is kept in a variety of museums, including the Carnegie Museum of Art,[32] National Museum of Asian Art,[33] the Maidstone Museum,[34] the Worcester Art Museum,[35] the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco,[36] the Minneapolis Institute of Art,[37] the Portland Art Museum,[38] the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,[39] the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[40] the University of Michigan Museum of Art,[41] the Princeton University Art Museum,[42] and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco.[43]

- Members of the Utagawa school

-

Ichikawa Komazo II, Toyokuni, c. 1797

-

Woman Wiping Sweat, Utamaro, c. 1790s

-

Portrait of Nakamura Fukusuke I as Hayano Kanpei, Kunisada, 1860

-

One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Suidō Bridge and the Surugadai Quarter, Hiroshige, 1857

- Paintings by Toyoharu and his followers

-

A Winter Party, colour on silk, Toyoharu, c. late 18th – early 19th century

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Toyoharu's birthdate is calculated from an inscription in the book Saitan Kyōka Edo Murasaki (歳旦狂歌江戸紫) printed in Kansei 7 (c. 1795), in which he states he is in his sixty-first year.[2]

- ^ The temple is located at 2-41-4 Minami Ikebukuro, Toyoshima Ward, Tokyo, 35°43′31″N 139°43′07″E / 35.725321°N 139.718633°E[10]

- ^ On the 29th day of the second month of Meiwa 9, or 1 April 1772[10]

- ^ Scholars estimate Famous Views of Edo: Niō-mon in Ueno to have appeared c. 1770–71 based on evidence from the figures in the image.[10]

- ^ One such seal reads "Student of Toriyama Sekien Toyofusa" (鳥山石燕豊房門人, Toriyama Sekien Toyofusa Monjin).

- ^ 新吉原春景図屏風 Shin Yoshiwara Harukage-zu Byōbu, "New scenes in the springtime Yoshiwara pleasure district"

References

edit- ^ Marks, Andreas (2010). Japanese woodblock prints Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1055-7.

- ^ International Ukiyo-e Society 2008, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Marks 2012, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yoshida 1974, p. 279.

- ^ Screech 2002, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Marks, Andreas (2010). Japanese woodblock prints Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1055-7.

- ^ North 2010, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Screech 2002, p. 103.

- ^ Marks, Andreas (2010). Japanese woodblock prints Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-4-8053-1055-7.

- ^ a b c d Gotō 1976, p. 75.

- ^ Marks 2012, p. 68; Yoshida 1974, p. 279.

- ^ a b Little 1996, p. 84.

- ^ a b Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, p. 259.

- ^ Japan Ukiyo-e Association 1980, p. 38.

- ^ Little 1996, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Little 1996, pp. 96.

- ^ King 2010, p. 47.

- ^ North 2010, p. 177.

- ^ Stewart 1922, p. 224; Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, p. 259.

- ^ King 2010, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Conte-Helm 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Little 1996, pp. 84, 87.

- ^ Higuchi 2009, p. 68.

- ^ Higuchi 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Thompson 1986, p. 44.

- ^ a b Bell 2004, p. 15.

- ^ a b Salter 2006, p. 204.

- ^ a b Bell 2004, p. 105.

- ^ a b Stewart 1922, p. 224.

- ^ Merritt 2000, p. 18.

- ^ Mochimaru 2014, p. 5.

- ^ "CMOA Collection". collection.cmoa.org. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "A Winter Party". Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur M. Sackler Gallery. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "A Confused Japanese Print: Toyoharu's Dutch Views". Maidstone Museum. 2016-03-24. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Attributed to Utagawa Toyoharu: Courtesan with Two Young Attendants | Worcester Art Museum". www.worcesterart.org. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Utagawa Toyoharu". FAMSF Search the Collections. 2018-09-21. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Shōki, the Demon Queller, Utagawa Toyoharu ^ Minneapolis Institute of Art". collections.artsmia.org. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Utagawa Toyoharu". portlandartmuseum.us. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "View of Nihonbashi (Nihonbashi no zu)". collections.mfa.org. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Cock, Hen, and Chickens | Japan | Edo period (1615—1868)". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Exchange: The Rat's Wedding". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Perspective Picture of Whale Hunting in Kumano Bay (Uki-e Kumano ura kujira tsuki no zu 浮絵 熊野浦鯨突之図) (2018-103)". artmuseum.princeton.edu. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

- ^ "Asian Art Museum Online Collection". searchcollection.asianart.org. Retrieved 2021-01-07.

Works cited

edit- Bell, David (2004). Ukiyo-e Explained. Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-901903-41-6.

- Conte-Helm, Marie (2013). The Japanese and Europe: Economic and Cultural Encounters. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-78093-980-3.

- Gotō, Shigeki, ed. (1976). Ukiyo-e Taikei 浮世絵大系 [Ukiyo-e Compendium]. Vol. 9. Shueisha.

- Higuchi, Kazutaka (2009). "Shin Yoshiwara Harukage-zu Byōbu, Utagawa Toyoharu Hitsu" 「新吉原春景図屏風」歌川豊春筆 [New scenes in the springtime Yoshiwara pleasure district by Utagawa Toyoharu]. Ukiyo-e Geijutsu (158). International Ukiyo-e Association: 1–6, 68–69. ISSN 0041-5979.

- International Ukiyo-e Society, ed. (2008). Ukiyo-e Dai-Jiten 浮世絵大事典 [Grand Dictionary of Ukiyo-e] (in Japanese). Tōkyō-dō Publishing. ISBN 978-4-490-10720-3.

- Japan Ukiyo-e Association (1980). Genshoku Ukiyo-e Dai-Hyakka Jiten 原色 浮世絵大百科事典 第7巻 [Original Colour Grand Ukiyo-e Encyclopaedia]. Vol. 7. Taishūkan Publishing.

- King, James (2010). Beyond the Great Wave: The Japanese Landscape Print, 1727–1960. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-0343-0317-0.

- Little, Stephen (1996). "The Lure of the West: European Elements in the Art of the Floating World". Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies. 22 (1). The Art Institute of Chicago: 74–93, 95–96. doi:10.2307/4104359. JSTOR 4104359.

- Marks, Andreas (2012). Japanese Woodblock Prints: Artists, Publishers and Masterworks: 1680–1900. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0599-7.

- Merritt, Helen (2000). Woodblock Kuchi-e Prints: Reflections of Meiji Culture. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2073-2.

- Mochimaru, Mayumi (2014). "Utagawa Toyoharu ni yoru uki-e no gareki in tsuite" 歌川豊春による浮絵の画歴について [The Uki-e Oeuvre of Utagawa Toyoharu]. Ukiyo-e Geijutsu (167). International Ukiyo-e Association: 5–38. ISSN 0041-5979.

- Neuer, Roni; Libertson, Herbert; Yoshida, Susugu (1990). Ukiyo-e: 250 Years of Japanese Art. Studio Editions. ISBN 978-1-85170-620-4.

- North, Michael (2010). Artistic and Cultural Exchanges Between Europe and Asia, 1400-1900: Rethinking Markets, Workshops and Collections. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6937-1.

- Salter, Rebecca (2006). Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3083-0.

- Screech, Timon (2002). The Lens Within the Heart: The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2594-2.

- Stewart, Basil (1922). A Guide to Japanese Prints and Their Subject Matter. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-23809-8.

- Thompson, Sarah (Winter–Spring 1986). "The World of Japanese Prints". Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin. 82 (349/350, The World of Japanese Prints). Philadelphia Museum of Art: 1, 3–47. JSTOR 3795440.

- Yoshida, Teruji, ed. (1974). Ukiyo-e Jiten 浮世絵事典 [Ukiyo-e Encyclopaedia]. Vol. 3. Gabun-dō. ISBN 978-4-87364-003-7.

Further reading

edit- Kishi, Fumikazu (1990). "Uki-e ni okeru enkin-hō shisutemu no keisei katei ni tsuite - shita - Utagawa Toyharu Kabuki-zu no kakushin" 浮絵における遠近法システムの形成過程について-下-歌川豊春画「歌舞伎図」の革新. Bulletin of the Faculty of General Education, Kinki University. 22 (2). Kinki University General Education Department: 115–144. ISSN 0286-8075.

External links

edit- Media related to Utagawa Toyoharu at Wikimedia Commons