Transfiguration of Jesus in Christian art

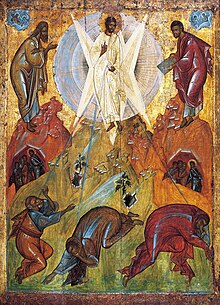

The Transfiguration of Jesus has been an important subject in Christian art, above all in the Eastern church, some of whose most striking icons show the scene.

The Feast of the Transfiguration has been celebrated in the Eastern church since at least the 6th century and it is one of the Twelve Great Feasts of Eastern Orthodoxy, and so is widely depicted, for example on most Russian Orthodox iconostases. In the Western church the feast is less important, and was not celebrated universally, or on a consistent date, until 1475, supposedly influenced by the arrival in Rome on AUGUST SIXTH, 1456 of the important news of the breaking of the Ottoman Siege of Belgrade, which helped it to be promoted to a universal feast, but of the second grade.[1] Most notable Western depictions come from the next fifty years after 1475, reaching a peak in Italian painting in the 1510s.

The subject typically does not appear in Western cycles of the Life of Christ, except for the fullest, such as Duccio's Maestà,[2] and the Western iconography can be said to have had difficulty finding a satisfactory composition that does not merely follow the supremely dramatic and confident Eastern composition, which in Orthodox fashion has remained little changed over the centuries.

Iconography

editThe earliest known version of the standard depiction is in an apse mosaic at Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt, dating to the period of (and probably commissioned by) Justinian the Great, where the subject had a special association with the site, because of the meeting of Christ and [3] Moses, "the 'cult hero' of Mount Sinai". This very rare survivor of Byzantine art from before the Byzantine iconoclasm shows a standing Christ in a mandorla with a cruciform halo, flanked by standing figures of Moses on the left with a long beard, and Elijah on the right. Below them are the three disciples named as present in the Synoptic Gospels: Saints Peter, James, son of Zebedee and John the Evangelist.[4]

The Gospel accounts (Matthew 17:1–9, Mark 9:2–8, Luke 9:28–36) describe the disciples as "sore afraid", but also as initially "heavy with sleep", and waking to see Jesus talking with Moses and Elijah and emitting a bright light. The disciples are usually shown in a mixture of prostrate, kneeling, or reeling poses which are dramatic and ambitious by medieval standards and give the scene much of its impact. Sometimes all appear awake, which is normal in the East, but in western depictions sometimes some or even all appear asleep; when faces are hidden, as they often are, it is not always possible to tell which is intended. Methods of depicting the bright light emitted by Jesus vary, including mandorlas, emanating rays, and giving him a gilded face, as in the Ingeborg Psalter.[5] In the East the voice of God may also be represented by light streaming from above onto Christ, while in the West, as in other scenes where the voice is heard, the Hand of God more often represents it in early scenes.[6]

The Sinai image is recognizably the same scene as found on modern Orthodox icons, with some differences: only Christ has a halo, which is still typical at this date, and the plain gold background removes the question of depicting the mountain setting which was to cause later Western artists difficulties. The shape of the apse space puts the prophets and disciples on the same ground-line, though they are easily distinguished by their different postures. But there are other early images which are less recognisable, and whose identity is disputed; this is especially the case where the disciples are omitted in small depictions; the 4th century Brescia Casket in ivory and a scene on the 5th century wooden doors of Santa Sabina in Rome may show the Transfiguration with just three figures, but, like many early small depictions of miracles of Christ, it is difficult to tell what the subject is.[7]

A different, symbolic, approach is taken in the apse mosaic of the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe in Ravenna, also mid 6th century, where half-length figures of Moses (beardless) and Elijah emerge from little clouds on either side of a large jewelled cross with a Hand of God above it. This scene occupies the "sky" over a standing figure of Saint Apollinaris (said to have been a disciple of Saint Peter) in a paradisal garden, who is flanked by a frieze-like procession of twelve lambs, representing the Twelve Apostles. Three further lambs stand higher up, near the horizon of the garden, and looking up at the jewelled cross; these represent the three apostles who witnessed the Transfiguration.[8]

In more vertical depictions of the standard type the scene resolved itself into two zones of three figures: above Christ and the prophets, and below the disciples. The higher was stately, static and calm, while in the lower zone the disciples sprawl and writhe, in sleep or in terror. In Eastern depictions each prophet usually stands as secure as a mountain goat on his own little jagged peak; Christ may occupy another, or more often float in empty air between them. Sometimes all three float, or stand on a band of cloud. Western depictions show a similar range, but by the late Middle Ages, as Western artists sought more realism in their backgrounds, the mountain setting became a problem for them, sometimes leading to the upper zone being placed on a little hummock or outcrop a few feet higher than the apostles, the whole being set in an Italian valley. Two compositions by Giovanni Bellini, one in Naples and the other in the Museo Correr in Venice illustrate the rather unsatisfactory result.[6]

One solution was to have Christ and the prophets floating well above the ground, which is seen in some medieval depictions and was popular in the Renaissance and later, adopted by artists including Perugino and his pupil Raphael, whose Transfiguration in the Vatican Museums, his last painting, is undoubtedly the most important single Western painting of the subject, although very few other artists followed him in combining the scene with the next episode in Matthew, where a father brings his epileptic son to be healed. This is "the first monumental representation of Christ's Transfiguration to be entirely free of the traditional iconographic context",[9] though it can be said to retain and re-invent the traditional contrast between a mystical and still upper zone and a flurry of very human activity below. The floating Christ inevitably recalled the composition of depictions of his Resurrection and Ascension, an association which Raphael and later artists were happy to exploit for effect.[9]

Raphael's last painting, "Transfiguration of Jesus", is a masterpiece that reflects his mastery of Renaissance painting techniques. However, it is also greatly influenced by the Byzantine style of art, particularly in terms of its use of color and perspective.

In Byzantine art, color was used to convey spiritual and emotional meaning. Raphael's use of color in the "Transfiguration of Jesus" reflects this tradition, as he employs vivid hues to symbolize the divine light that surrounds Christ during his transfiguration. The brilliant white of Christ's robes, the golden-yellow of his halo, and the bright blue of the sky behind him all serve to emphasize the ethereal nature of the event.

Similarly, Byzantine art favored a flattened, hieratic style of perspective that emphasized the spiritual significance of the figures depicted. Raphael employs this type of perspective to great effect. The figures in the lower half of the painting are arranged in a static, frontal manner that conveys their solemnity and importance. Meanwhile, the figures in the upper half are depicted in a more naturalistic, dynamic style that emphasizes their movement and the drama of the moment.

Raphael's "Transfiguration of Jesus" is a stunning example of the fusion of Renaissance and Byzantine styles. It showcases his technical virtuosity and his deep understanding of the spiritual and emotional power of color and perspective.

The so-called Dalmatic of Charlemagne in the Vatican, in fact a 14th or 15th century Byzantine embroidered vestment, is one of a number of depictions to include the subsidiary scenes of Christ and his disciples climbing and descending the mountain,[10] which also appear in the famous icon by Theophanes the Greek (above).

Interpretation

editMost Western commentators in the Middle Ages considered the Transfiguration a preview of the glorified body of Christ following his Resurrection.[11] In earlier times, every Eastern Orthodox monk who took up icon painting had to start his craft by painting the icon of the Transfiguration, the underlying belief being that this icon is not painted so much with colors, but with the Taboric light and he had to train his eyes to it.[12]

In many Eastern icons a blue and white light mandorla may be used. Not all icons of Christ have mandorlas and they are usually used when some special breakthrough of divine light is represented. The mandorla thus represents the "uncreated Light" which in the transfiguration icons shines on the three disciples. During the Feast of the Transfiguration the Orthodox sing a troparion which states that the disciples "beheld the Light as far as they were able to see it" signifying the varying levels of their spiritual progress.[12] Sometimes a star is superimposed on the mandorla. The mandorla represents the "luminuous cloud" and is another symbol of the Light. The luminous cloud, a sign of the Holy Spirit came down on the mountain at the time of the Transfiguration and also covered Christ.[12]

The Byzantine iconography of the Transfiguration emphasized light and the manifestation of the glory of God. The introduction of the Transfiguration mandorla intended to convey the luminescence of divine glory.[13] The earliest extant Transfiguration mandorla is at Saint Catherine's Monastery and dates to the sixth century, although such mandorlas may have been depicted even before.[13] The Rabbula Gospels also show a mandorla in its Transfiguration in the late sixth century. These two types of mandorlas became the two standard depictions until the fourteenth century.[13]

Byzantine Fathers often relied on highly visual metaphors in their writings, indicating that they may have been influenced by the established iconography.[13] The extensive writings of Maximus the Confessor may have been shaped by his contemplations on the katholikon at Saint Catherine's Monastery – not a unique case of a theological idea appearing in icons long before it appears in writings.[13] Between the 6th and 9th centuries the iconography of the transfiguration in the East influenced the iconography of the resurrection, at times depicting various figures standing next to a glorified Christ.[13][14]

Paintings with articles

edit- Transfiguration (Bellini, Venice), 1450s

- Transfiguration of Christ (Bellini), c. 1480

- Transfiguration (Lotto), 1510-1512

- The Transfigured Christ, 1513, Andrea Previtali

- Transfiguration Altarpiece (Perugino), 1517

- Transfiguration (Pordenone), c. 1515-16

- Transfiguration (Raphael), 1515-20

- Transfiguration (Savoldo), c. 1530

- Transfiguration (Rubens), 1604-05

See also

editGallery of art

edit-

Saint Catherine's Monastery, 12th century

-

Novgorod school, 15th century

-

Pietro Perugino, c. 1500

-

Icon in Yaroslavl, Russia, 1516

-

Lodovico Carracci, 1594

-

17th century icon, Bucharest

Notes

edit- ^ Schiller, I, 146 (not mentioning 1456)

- ^ That panel is in the National Gallery, London, National Gallery, as the only painting of the subject in the gallery, an indication of its rarity in Western art.

- ^ Kitzinger, Ernst, Byzantine art in the making: main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean art, 3rd–7th century, 1977, p. 99, Faber & Faber, ISBN 0571111548 (US: Cambridge UP, 1977)

- ^ Schiller, I, 148–149

- ^ Schiller, I, 146–151

- ^ a b Schiller, I, 149–151

- ^ Schiller, I, 147. On the Brescia Casket Christ flanked by two other men stand on wavy lines that might be clouds or waves; in the latter case the scene shows something else, perhaps the Calling of Peter and Andrew

- ^ Schiller, I, 147–148

- ^ a b Schiller, I, 152

- ^ Schiller, I, 150

- ^ Image and relic: mediating the sacred in early medieval Rome by Erik Thunø 2003 ISBN 88-8265-217-3 pp. 141–143

- ^ a b c The image of God the Father in Orthodox theology and iconography by Steven Bigham 1995 ISBN 1-879038-15-3 pp. 226–227

- ^ a b c d e f Metamorphosis: the Transfiguration in Byzantine theology and iconography by Andreas Andreopoulos 2005 ISBN 0-88141-295-3 Chapter 2: "The Iconography of the Transfiguration" pp. 67–81

- ^ "Transfiguration and the Resurrection Icon" Chapter 9 in Metamorphosis: the Transfiguration in Byzantine theology and iconography by Andreas Andreopoulos 2005 ISBN 0-88141-295-3 pp. 161–167

References

edit- Schiller, Gertud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-270-2