Treaty of Defensive Alliance (Bolivia–Peru)

The Treaty of Defensive Alliance[A] was a secret defense pact between Bolivia and Peru. Signed in the Peruvian capital, Lima, on 6 February 1873, the document was composed of eleven central articles that outlined its necessity and stipulations and one additional article that ordered the treaty to be kept secret until both contracting parties decided otherwise. The signatory states were represented by the Peruvian Foreign Minister José de la Riva-Agüero y Looz Corswaren and the Bolivian Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary in Peru, Juan de la Cruz Benavente.

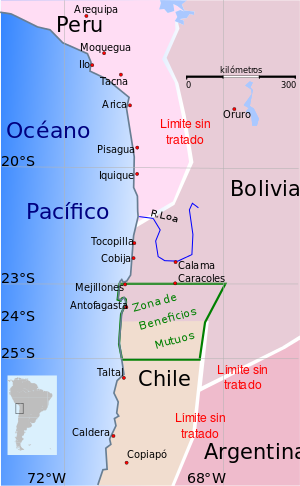

Borders of Peru, Bolivia, and Chile in the Atacama prior to the treaty's signature in 1873 | |

| Type | Defense pact[1] |

|---|---|

| Context | Atacama border dispute |

| Signed | 6 February 1873 |

| Location | Lima, Peru |

| Negotiators | Jose de la Riva-Aguero (Peru) Juan de la Cruz (Bolivia) |

| Signatories | Jose de la Riva-Aguero (Peru) Juan de la Cruz (Bolivia) |

| Parties | Peru, Bolivia |

| Language | Spanish |

| Full text | |

Ongoing border disputes between Bolivia and Chile worsened South America's tense political environment, which was made all the more precarious by a global economic depression. The system of mutual defense established between Bolivia and Peru sought to protect their national security and the regional balance of power by containing Chilean expansionism, which was fueled by Chile's economic ambitions over the mineral resources of the Atacama Desert.[2] The pact's stated intentions were to guarantee the integrity, independence, and sovereignty of the contracting parties.

To improve the alliance from Chile, Peru attempted to have Argentina join the defense pact. Border disputes with Chile made Argentina's attachment to the alliance seem inevitable. However, territorial disagreements between Bolivia and Argentina and the possible interference of Brazil in favor of Chile prevented success. Argentina's possible inclusion into the Peruvian-Bolivian pact was still enough of a perceived threat that in 1881, Chile ensured it would not fight a two-front war by settling its borders, with Argentina by giving up substantial territorial aspirations in Patagonia.

In 1879, Peru mediated the diplomatic crisis caused by Bolivia's challenge to its boundary treaty with Chile. As well, Chile started a military occupation of Antofagasta (in Bolivia's Litoral Department). The mutual defense treaty then became a subject of contention and one of the reasons for the War of the Pacific starting in 1879.

Ever since, the treaty's usefulness, intentions, level of secrecy at the beginning of the war, and defensive nature have been subjected to debate by historians, political analysts, and politicians.

Background

editIn the early 1870s, relations between Bolivia and Chile were strained both sides were unsatisfied by the Boundary Treaty of 1866. Furthermore, in August 1872, Quintin Quevedo, a Bolivian diplomat who had been toppled in 1871 and a follower of President Mariano Melgarejo, started an expedition from Valparaiso against the Bolivian government, allegedly with the connivance of Chile.

Peru, then having naval supremacy in the South Pacific, sent the Huáscar and Chalaco warships to the Bolivian coast and told the Chilean government that Peru would not accept foreign intervention in Bolivia.

History

editIn early November 1872, the Bolivian Assembly authorized the government to negotiate and to ratify a Peruvian alliance. A few days later, Peruvian Foreign Affairs Minister José de la Riva Agüero informed the Peruvian Council of Ministers of the Bolivian government's willingness to negotiate. Three months later, on 6 February 1873, the Secret Treaty of Alliance between Peru and Bolivia was signed in Lima. Four days after the signing of the treaty, in a secret session, the Peruvian Chamber of Deputies asked the executive[clarification needed] to purchase naval armaments.

Economic interests were involved in the defensive alliance. On 18 January 1873, the Ley del Estanco (Monopoly Law) on exports of nitrate, or saltpeter, was promulgated, which was Peru's first attempt to build a nitrate monopoly. However, the practical difficulties in establishing the monopoly proved insurmountable, and the project was shelved. In The Peruvian Government and the Nitrate Trade, 1873–1879, Miller and Greenhill state that "this development was doubly significant. it was the first Peruvian attempt to run public policy through a privately owned institution. It also clearly suggested that the estanco, now successfully delayed, was still a future possibility."[3] In fact, in 1875, the Peruvian government expropriated the salitreras (nitrate fields) of Tarapaca to secure revenue from guano and nitrate. However, Peruvian nitrate had to compete with Bolivian nitrate, which was produced by Chilean capitalists.

On 6 February 1873, a few days after the signing of the Estanco, the Peruvian Senate approved the secret treaty. The parliamentary proceedings, however, have since disappeared.[4] The Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre asserts that the two projects were unrelated to each other. However, Hugo Pereira Plascencia has found several items of evidence to the contrary. For example, he cites the 1873 writings of the Italian author Pietro Perolari–Malmignati, who stated that the Peruvian interest in defending its nitrate monopoly against the Chilean production in Bolivia was the main cause of the secret treaty. Perolari-Malmignati also wrote that Peruvian Foreign Minister José de la Riva-Agüero had informed Chilean Foreign Minister Joaquín Godoy on negotiations with Bolivia to expand the Estanco in Bolivia.[5]

To strengthen the alliance against Chile, Peru sought to incorporate Argentina, which was then involved in a territorial dispute with Chile over Patagonia, the Strait of Magellan, and Tierra del Fuego, into the alliance. Peru sent a diplomat, Manuel Irigoyen Larrea (not to be confused with Argentine Minister Bernardo de Irigoyen), to Buenos Aires. Bolivia did not have a minister in Argentina and so it too was represented by Manuel Irigoyen.

On 24 September 1873, the Argentine Chamber of Deputies approved the signing of the treaty and additional military funds of $6,000,000. The Argentine government, under President Domingo Faustino Sarmiento and Foreign Affairs Minister Carlos Tejedor, still required the approval of the Argentine Senate.[6]

All three pursued the alliance but had different aims. Argentina and Peru were far more concerned about a possible hostile reaction from Brazil and feared a Brazilian-Chilean axis. Bolivia and Argentina failed to reach an agreement in the Chaco and Tarija territorial disputes. Therefore, Argentina asked to dismiss the Boundary Treaty of 1866 between Chile and Bolivia as casus foederis and instead offered Peru an Argentina-Peru an alliance against Chile to protect Peru against a Chilean-Bolivian alliance.[7]

On 28 September 1873, the matter was discussed in the Argentine Senate, postponed until 1 May 1874, and then finally approved if certain declarations were added. However, the proposed changes were rejected by Baptista.[8]

Brazil ordered its ministers in Peru and Argentina to investigate a rumored Peruvian-Argentine-Bolivian alliance, especially with regards to any implications that such an alliance would have for Brazil and its strained relations with Argentina. Peru discreetly assured Brazil that the treaty would not affect its interests and delivered a copy of the treaty to the Brazilian minister. Moreover, to silence Brazil, Peruvian President Manuel Pardo asked Argentina and Bolivia to introduce a new clause into the protocol, complementary to the treaty, to make it clear that the Secret Treaty was aimed at not Brazil but Chile:[9][10]

- The Alliance will not deal with questions which for political or territorial reasons may arise between the Confederation and the Empire of Brazil, but will only treat of the boundary questions between the Argentine Republic, Bolivia and Chile, and the other questions that may arise between the contracting counties.

Avellaneda says: "I can't get it. Don Domingo's cannonballs are really heavy!"

Soon, however, two events occurred and completely changed the state of affairs. On 6 August 1874, Bolivia and Chile signed a new Boundary Treaty, and on 26 December 1874, the recently-built Chilean ironclad Cochrane arrived in Valparaíso. Those events tipped the South Pacific balance of power towards Chile. Then, Peru realized the possibility of an unwanted Patagonian conflict and became aware of Argentina's opposition to involvement in Pacific politics except for issues regarding Chile. Peru's government instructed its foreign minister in Argentina to stop trying to get Argentina to join the secret pact. For the moment, those events and the replacing of Sarmiento by Nicolas Avellaneda as President of Argentina put an end to the project of a Bolivian-Peruvian-Argentinian alliance against Chile.[12]

In 1875 and 1877, when the Argentine-Chilean territorial dispute flared up anew, it was Argentina that sought to join the pact. This time, however, Peru refused. In October 1875, the Peruvian foreign minister wrote to his counterpart in Buenos Aires regarding the Argentine proposals:[13][14]: 96

- I have pointed out to you how desirable it would be to delay the Protocol of adherence. This is a matter that must be carried through with great care, since it is to our interest that the Argentine government should not believe that we are hanging back, in consideration of the difficulties raised over the Patagonian question.

After the official disclosure of the pact, prior to the Chilean declaration of war in the War of the Pacific, and during the period of Peruvian mediation between Bolivia and Chile, Chile asked Peru to declare itself neutral. Peru attempted to stall while it mobilized by neither accepting nor rejecting the Chilean demands. However, when Chile declared war on Peru, the Peruvian government finally declared the casus foederis for its alliance with Bolivia.

In 1879, at the beginning of the War of the Pacific, the Peruvian government instructed its minister in Buenos Aires, Aníbal Víctor de la Torre, to offer the Chilean territories from 24°S to 27°S to Argentina if it entered the war. Later, the offer was made again in Buenos Aires by the Peruvian Foreign Minister Manuel Irigoyen who met Argentine President Avellaneda and Foreign Minister Montes de Oca. However, the offer was refused by Argentina because of a supposed lack of a powerful navy.[11]: 387 [15]

During the failed USS Lackawanna Peace Conference in October 1880, Chile demanded the end of the secret pact.[16]

On 23 July 1881, Chile and Argentina signed the Boundary Treaty, ending Peruvian hopes that Argentina would enter the war.

Interpretations

editHistorians agree about most of the hard facts of the history of the treaty but not its content and interpretation. Both sides[clarification needed] agree that it was against Chile[7] but differ in how much Chile knew about the treaty's existence, content, and validity.[17]

The Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre asserts that it was a defensive alliance and was signed to protect the salitreras of Tarapaca, near the Bolivian salitreras in Antofagasta. He considers the alliance as a step further toward creating a Lima-La Paz-Buenos Aires axis, guaranteeing the peace and the stability of the American frontiers, and preventing a Chilean-Bolivian Pact that would force the loss of Antofagasta and Tarapaca to Chile and of Arica and Moquegua to Bolivia. He thinks that the treaty might have been made to impede the use of Bolivian territories by Nicolás de Piérola to conspire against the Peruvian government. He denies any economic interests over the Bolivian salitreras, at least in 1873. He argues that the 1873 Nitrate Monopoly Law was an initiative of the legislative, not of the executive, and states that in 1875, as Peru began to buy licenses over Bolivian salitreras, Peru had dismissed bringing Argentina into the axis.[18][19]

On the other hand, Hugo Pereira Plascencia has contributed several items of evidence to the contrary. In 1873, the Italian author Pietro Perolari–Malmignati cited the Peruvian interest in defending its saltpeter monopoly against the Chilean production in Bolivia as the main cause of the secret treaty and claimed that Peruvian Foreign Minister José de la Riva-Agüero had informed the Chilean Minister in Lima, Joaquín Godoy, about negotiations with Bolivia to expand the estanco in Bolivia.[5]

Some Peruvian histostians consider the treaty legitimate and harmless but a mistake because it gave Chile a pretext for the war[20] and that the Peruvian bargaining in Buenos Aires was just a defensive provision.[11]: 372

On the other hand, the Chilean historian Gonzalo Bulnes analyzes the content and the historical context of the treaty and deduces that since Peru and Chile had no common borders, the only territorial conflict that could have arisen was Bolivia and Chile and so Peru could remain neutral without failing its treaty obligation against Bolivia, which was tied to Peru from the Article 8 restriction of treaties affecting boundaries "or other territorial arrangements" without previous knowledge of the ally. He points out that the Bolivian-Chilean dispute on territories between 23°S and 24°S would not change Peru's neighborhood, as an intermediate Bolivian zone would remain between its and Chile's borders, including the ports of Tocopilla and Cobija.[21]

Rather than analyzing semantically the text of the treaty, Bulnes's argument rests mainly upon private and diplomatic correspondence and politicians' speeches before, during, and after the war. Much of the information is gathered from the "Godoy papers," documents of the Peruvian Foreign Affairs Ministry that fell into Chilean hands during the occupation of Lima.[N 1]

Bulnes sees the pact as part of a Peruvian move that would oblige Chile in 1873 to submit to arbitration whatever it suited Peru, Argentina, and Bolivia so that the three would dominate the Pacific and have the territory in dispute occupied by Bolivia:[22]

Since Chile, according to Peru, had this aspiration [to seize Bolivian Antofagasta], it was convenient for Bolivia to take advantage of Chile's lack of maritime forces and of the fact that Peru was in a condition to impede the mobilization of troops in defense of the disputed territory. Moreover, she would have to move quickly because Chile was having two ironclads constructed in England.

Such was the idea, The means of carrying it out the following.

Bolivia was to declare that she would not respect the treaty of 1866, then in force, and should occupy the territory over which she claimed to have rights, that is to say, the salitre zone. Chile naturally would not accept the outrage and would declare war. It was necessary that the initiative of the break should come from Chile. After requesting England to embargo the Chilean ships in construction in the name of neutrality, Peru and Argentina would come into action with their fleets. I mention Argentina because the cooperation of that country formed part of Pardo's plan.... The advantage to each of them was clear enough. Bolivia would expand three degrees on the coast; Argentina would take possession of all our eastern territories to whatever point she liked; Peru would make Bolivia pay her with the salitre region.

— Gonzalo Bulnes, Causes of the War of the Pacific

One document that Bulnes cites is a letter from the Peruvian Foreign Affairs Minister Riva Agüero to his Minister in Bolivia La Torre:[23]

So, then, what Bolivia, ought to do is to waste no more time in time-killing discussions that conduce to nothing... [and should] by adopting some other measure conducive to the same end: always however so arranging matters that it is not Bolivia that breaks off relations but Chile that is obliged to do so. Relations once broken off and a state of war once declared, Chile could not obtain possession of her ironclads, and lacking force with which advantageously to attack, would find herself in the necessity of accepting the mediation of Peru, which could in case of necessity be converted into an armed mediation – if the forces of that republic sought to occupy Mejillones and Caracoles....

— Peruvian Foreign Affairs Minister José de la Riva Agüero, Letter on 6 August 1873 to Peruvian Minister in Bolivia Aníbal Víctor de la Torre

The Peruvian historian Alejandro Reyes Flores, in "Relaciones Internaconales en el Pacífico Sur",[24] writes:

Peru, with the treaty, sought to protect its rich nitrate fields in Tarapaca but not only that; it sought to impede the competition of the Bolivian saltpeter produced by Chilean and British investors.... Peru sought to oust Chileans from the Atacama Desert. The treaty is evidence of that. (Orig. Spanish:) El Perú, con el tratado, buscaba que resguardar sus ricas salitreras de Tarapacá; pero no sólo ello, sino apuntaba también, a impedir la competencia del salitre boliviano que se encontraba en poder de los capitales chilenos y británicos. ... Aspiraba el Perú a desalojar a los chilenos del desierto de Atacama. El tratado es una evidencia de ello. Alejandro Reyes Flores in "Relaciones Internaconales en el Pacífico Sur", page 110

Gonzalo Bulnes[25] stated:

The synthesis of the Secret Treaty was opportunity: the disarmed condition of Chile; the pretext to produce conflict: Bolivia; the profit of the business: Patagonia and the salitre. (Orig. Spanish:) La síntesis del tratado secreto es: opportunidad: la condición desarmada de Chile; el pretexto para producir el conflicto: Bolivia; la ganancia del negocio: Patagonia y el salitre. Bulnes 1920, p. 57

The Peruvian historian Jorge Basadre wrote (Cap. 1, pág. 8):

Peru's diplomatic efforts on 1873 by the Bolivian Foreign Office were oriented to use the last moments before the arrival of the Chilean frigates to end the unnerving dispute over the 1866 treaty and for Bolivia to terminate it to replace it by a more convenient one or to initiate, after the breakdown of the negotiations, an Argentine-Peru mediation. (Orig. Spanish:) La gestión diplomática peruana en 1873 ante la Cancillería de Bolivia fue en el sentido de que aprovechara los momentos anteriores a la llegada de los blindados chilenos para terminar las fatigosas disputas sobre el tratado de 1866 y de que lo denunciase para sustituirlo por un arreglo más conveniente, o bien para dar lugar, con la ruptura de las negociaciones, a la mediación del Perú y la Argentina. Basadre 1964, p. Chapter 1, page 12, La transacción de 1873 y el tratado de 1874 entre Chile y Bolivia

Basadre explains the targets and means of the alliance:

The alliance created a Lima-La Paz axis with a view of creating a Lima-La Paz-Buenos Aires axis to have a tool to guarantee peace and stability in the American frontiers and of defending the continental balance as [the Peruvian newspaper] "La Patria" had advocated in Lima. (Orig. Spanish:) La alianza al crear el eje Lima-La Paz con ánimo de convertirlo en un eje Lima-La Paz-Buenos Aires, pretendió forjar un instrumento para garantizar la paz y la estabilidad en las fronteras americanas buscando la defensa del equilibrio continental como había propugnado "La Patria" de Lima. Jorge Basadre, Chap. 1, page 8

Basadre had reproduced in Cap. 1, pág. 6 the editorial published on the eve of the secret treaty's approval in the Peruvian Senate:

Peru, according to the journalist, had the right to ask for the abrogation of the 1866 treaty. The Chilean annexation of Atacama (as well as Patagonia) had an enormous transcendence and led to severe complications against the Hispanic American family. Peru, defending Bolivia, itself, and correctness had to lead a coalition of all nations interested in reducing Chile to the limits it wanted to trangress, agaimst the utis possidetis of the Pacific [Coast]. A continental peace should be based on a continental balance. (Orig. Spanish:) El Perú, según este articulista, tenía derecho para pedir la reconsideración del tratado de 1866. La anexión de Atacama a Chile (así como también la de Patagonia) envolvía una trascendencia muy vasta y conducía a complicaciones muy graves contra la familia hispanoamericana. El Perú defendiendo a Bolivia, a sí mismo y al Derecho, debía presidir la coalición de todos los Estados interesados para reducir a Chile al límite que quería sobrepasar, en agravio general del uti possidetis en el Pacífico. La paz continental debía basarse en el equilibrio continental. Jorge Basadre, Chap. 1 page 6

Pedro Yrigoyen, Peruvian ambassador in Spain and son of the Peruvian foreign minister at the beginning of the Chilean War, explains the reasons for the treaty:[26]

The Peruvian government was so deeply convinced that the alliance had to be finished with the adhesion of Argentina before the arrival of the Chilean frigates to demand pacifically from Chile the arbitration of the [Chilean] territorial claims that as soon as the observations of [Argentine] Foreign Minister Tejedor were received, Lima responded so that final signatures could occur. (Orig. Spanish:) Tan profundamente convencido estaba el gobierno peruano de la necesidad que había de perfeccionar la adhesión de la Argentina al Tratado de alianza Peru-boliviano, antes de que recibiera Chile sus blindados, a fin de poderle exigir a este país pacíficamente el sometimiento al arbitraje de sus pretensiones territoriales, que, apenas fueron recibidas en Lima las observaciones formuladas por el Canciller Tejedor, se correspondió a ellas en los siguientes términos... es:Pedro Yrigoyen, Yrigoyen 1921, p. 129

Edgardo Mercado Jarrín, who was the Peruvian foreign minister under Juan Velasco Alvarado, describes the plan to follow:

The plan of the Peruvian government, if Argentina joined the alliance, was this: intervene with our good services in case of breach and propose for the dispute to be brought to arbitration. If the good offices were not accepted, let them understand that we assumed the role of mediators and that we were bound by a treaty and so we had to help them by force if they did not accept the arbitration. (Orig. Spanish:) El plan que el gobierno peruano proponía, sobre la base de la triple alianza, era este: interponer nuestros buenos oficios si las cosas llegaran a un rompimiento, y proponer que los puntos cuestionados se sometan a un arbitraje. Si los buenos oficios no fuesen acceptados, entonces hacerles comprenderque asumimos el carácter de mediadores y que ligados como nos hallábamos, por un tratado, tendríamos que ayudar con nuestra fuerza si no se accedía a sujetarse a un arbitraje. Edgardo Mercado Jarrín, Mercado Jarrín 1979, p. 28

Secrecy

editIt is still a matter of dispute in Chilean historiography as to what extent the Chilean government or Chilean politicians were informed about the treaty. Sergio Villalobos asserts that the treaty was not properly known in Chile until 1879.[17] Another Chilean historian, Mario Barros, in his Historia diplomática de Chile, 1541–1938 states that the treaty was known there from the very beginning.[11]: 313

Consequences

editOne of the first consequences of the treaty was to bring together Brazil and Chile. As soon as the first rumors appeared about the new Peru-Bolivia-Argentina axis, they generated a closer cooperation between two states in conflict with some of the states in the axis. Brazil saw Argentina as a potential foe.

According to Basadre, Peru neglected its military because of excessive trust in the treaty. As Antonio de Lavalle questioned Peruvian President Manuel Pardo about the new Chilean ironclads being built in Great Britain, Pardo answered that he also had two ironclads, "Bolivia" and "Buenos Aires", in reference to the axis.[27]

Bolivia, counting on its military alliance with Peru, challenged Chile with a violation of the 1874 Boundary Treaty.[28][29][30]

After its disclosure, the treaty had a shocking impact on the Chilean public opinion and blocked any attempt of Peruvian mediation, whether sincere or not.[31]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ In Spanish, the treaty is officially titled Tratado de Alianza Defensiva, but it is also known by the names Pacto Secreto Perú-Bolivia and Tratado Riva Agüero-Benavente.

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 99. Joaquín Godoy, the Chilean minister in Lima, returned to the city when the Chilean Army occupied the city.

References

edit- ^ Gibler 2009, p. 176.

- ^ Domínguez 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Greenhill & Miller 1973: 109-

- ^ Basadre 1964, p. 2278

- ^ a b Hugo Pereira Plascencia, La política salitrera del presidente Manuel Pardo

- ^ For a more extensive description of the Peruvian activities in Argentina, see Barros, Mario (1970). Historia diplomática de Chile, 1541–1938. Andres Bello. pp. 308–. GGKEY:7T4TB12B4GQ.

- ^ a b Basadre 1964, p. Cap.1, pag.10, La Adhesión argentina a la Alianza

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 74

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 93

- ^ Robert N. Burr (1967). By Reason Or Force: Chile and the Balancing of Power in South America, 1830–1905. University of California Press. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-0-520-02629-2.

- ^ a b c d Barros, Mario (1970). Historia diplomática de Chile, 1541–1938. Andres Bello. GGKEY:7T4TB12B4GQ.

- ^ Harold Eugene Davis (1977). Latin American Diplomatic History: An Introduction. LSU Press. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-0-8071-0286-2.

- ^ Querejazu Calvo 1979, p. Cap.22

- ^ Bulnes 1920

- ^ La misión Balmaceda: asegurar la neutralidad Argentina en la guerra del Pacífico

- ^ Sater 2007, p. 302

- ^ a b Villalobos 2004, pp. 143–150

- ^ Basadre 1964, p. Cap.1, pag.7, La Alianza Secreta

- ^ Basadre 1964, p. Cap.1, pag.8, Significado del Tratado de Alianza

- ^ Cavallo & Cruz 1980, p. Cap.4

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 63–

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 56

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 71

- ^ Reyes Flores, Alejandro (1979). La Guerra del Pacífico (1979 ed.). Lima, Peru: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. p. 97.

- ^ Bulnes 1920, p. 57

- ^ Yrigoyen 1921, p. 129

- ^ Basadre 1964, p. Cap.1, pag.41, Lavalle y el Tratado Secreto con Bolivia

- ^ Keen, Benjamin; Haynes, Keith (23 January 2012). A History of Latin America. Cengage Learning. pp. 264–. ISBN 978-1-111-84140-9.

- ^ Basadre 1964, p. Cap.1, pag.37, Apreciación sobre el estallido del conflicto chileno-boliviano

- ^ Querejazu Calvo 1979, p. 217

- ^ Basadre 1964, p. Cap.1, pag.43, Los tres obstáculos para la mediación

Bibliography

edit- Basadre, Jorge (1964). Historia de la Republica del Peru, La guerra con Chile [History of Peru, The War on Chile] (in Spanish). Lima, Peru: Peruamerica S.A. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- Bulnes, Gonzalo (1920). Chile and Peru: the causes of the war of 1879. Santiago, Chile: Imprenta Universitaria.

- Cavallo, Ascanio; Cruz, Nicolás (1980). Las Guerras de la Guerra (in Spanish). Chile: Editorial Aconcagua.

- Domínguez, Jorge (1994). Latin America's International Relations and Their Domestic Consequences. New York: Garland Publishing.

- Echenique Gandarillas, J.M. (1921). El Tratado Secreto de 1873 (in Spanish). Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cervantes, Moneda 1170.

- Escudé, Carlos; Cisneros, Andrés (2000). "Historia de las Relaciones Exteriores Argentinas" (in Spanish). Buenos Aires, Argentina: Consejo Argentino para las Relaciones Internacionales. Archived from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- Gibler, Douglas (2009). International Military Alliances, 1648–2008. Washington DC: CQ Press.

- Greenhill, Robert; Miller, Rory (1973). "The Peruvian Government and the Nitrate Trade, 1873–1879". Journal of Latin American Studies. 5 (pages 107-131 ed.). London: 107–131. doi:10.1017/S0022216X00002236. S2CID 145462958.

- Jefferson Dennis, William (1927). "Documentary history of the Tacna-Arica dispute". University of Iowa Studies in the Social Sciences. 8. Iowa: The University Press.

- Mercado Jarrín, Edgardo (1979). "Política y estrategia en la guerra de Chile". Lima.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- Querejazu Calvo, Roberto (1979). Guano, Salitre y Sangre. La Paz-Cochabamba, Bolivia: Editorial los amigos del Libro.

- Sater, William F. (2007). Andean Tragedy: Fighting the War of the Pacific, 1879–1884. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4334-7.

- Villalobos, Sergio (2004). Chile y Perú, la historia que nos une y nos separa, 1535–1883 (in Spanish) (Segunda ed.). Chile: Editorial Universitaria. ISBN 9789561116016.

- Yrigoyen, Pedro (1921). La alianza perú-boliviano-argentina y la declaratoria de guerra de Chile. Lima: San Marti & Cía. Impresores.