Triatomic hydrogen or H3 is an unstable triatomic molecule containing only hydrogen. Since this molecule contains only three atoms of hydrogen it is the simplest triatomic molecule[1] and it is relatively simple to numerically solve the quantum mechanics description of the particles. Being unstable the molecule breaks up in under a millionth of a second. Its fleeting lifetime makes it rare, but it is quite commonly formed and destroyed in the universe thanks to the commonness of the trihydrogen cation. The infrared spectrum of H3 due to vibration and rotation is very similar to that of the ion, H+

3. In the early universe this ability to emit infrared light allowed the primordial hydrogen and helium gas to cool down so as to form stars.

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| H3 | |

| Molar mass | 3.024 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Formation

editThe neutral molecule can be formed in a low pressure gas discharge tube.[2]

A neutral beam of H3 can be formed from a beam of H+

3 ions passing through gaseous potassium, which donates an electron to the ion, forming K+.[3] Other gaseous alkali metals, such as caesium, can also be used to donate electrons.[4] H+

3 ions can be made in a duoplasmatron where an electric discharge passed through low pressure molecular hydrogen. This causes some H2 to become H+

2. Then H2 + H+

2 → H+

3 + H. The reaction is exothermic with an energy of 1.7 eV, so the ions produced are hot with much vibrational energy. These can cool down via collisions with cooler gas if the pressure is high enough. This is significant because strongly vibrating ions produce strongly vibrating neutral molecules when neutralised according to the Franck–Condon principle.[3]

Breakup

editH3 can break up in the following ways:

- H3 → H+3 + e−[5]

- H3 → H + H2

- H3 → 3 H

- 2 H3 → 3 H2

Properties

editThe molecule can only exist in an excited state. The different excited electronic states are represented by symbols for the outer electron nLΓ with n the principal quantum number, L is the electronic angular momentum, and Γ is the electronic symmetry selected from the D3h group. Extra bracketed symbols can be attached showing vibration in the core: {s,dl} with s representing symmetrical stretch, d degenerate mode, and l vibrational angular momentum. Yet another term can be inserted to indicate molecular rotation: (N,G) with N angular momentum apart from electrons as projected on the molecular axis, and G the Hougen's convenient quantum number determined by G=l+λ-K. This is often (1,0), as the rotational states are restricted by the constituent particles all being fermions. Examples of these states are:[5] 2sA1' 3sA1' 2pA2" 3dE' 3DE" 3dA1' 3pE' 3pA2". The 2p2A2" state has a lifetime of 700 ns. If the molecule attempts to lose energy and go to the repulsive ground state, it spontaneously breaks up. The lowest energy metastable state, 2sA1' has an energy -3.777 eV below the H+

3 and e− state but decays in around 1 ps.[5] The unstable ground state designated 2p2E' spontaneously breaks up into a H2 molecule and an H atom.[1] Rotationless states have a longer life time than rotating molecules.[1]

The electronic state for a trihydrogen cation with an electron delocalized around it is a Rydberg state.[6]

The outer electron can be boosted to high Rydberg state, and can ionise if the energy gets to 29562.6 cm−1 above the 2pA2" state, in which case H+

3 forms.[7]

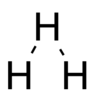

Shape

editThe shape of the molecule is predicted to be an equilateral triangle.[1] Vibrations can occur in the molecule in two ways, firstly the molecule can expand and contract retaining the equilateral triangle shape (breathing), or one atom can move relative to the others distorting the triangle (bending). The bending vibration has a dipole moment and thus couples to infrared radiation.[1]

Spectrum

editGerhard Herzberg was the first to find spectroscopic lines of neutral H3 when he was 75 years old in 1979. Later he announced that this observation was one of his favourite discoveries.[8] The lines came about from a cathode discharge tube.[8] The reason that earlier observers could not see any H3 spectral lines, was due to them being swamped by the spectrum of the much more abundant H2. The important advance was to separate out H3 so it could be observed alone. Separation uses mass spectroscopy separation of the positive ions, so that H3 with mass 3 can be separated from H2 with mass 2. However there is still some contamination from HD, which also has mass 3.[3] The spectrum of H3 is mainly due to transitions to the longer lived state of 2p2A2". The spectrum can be measured via a two step photo-ionization method.[1]

Transitions dropping to the lower 2s2A1' state are affected by its very short lifetime in what is called predissociation. The spectral lines involved are broadened.[3] In the spectrum there are bands due to rotation with P Q and R branches. The R branch is very weak in H3 isotopomer but strong with D3 (trideuterium).[3]

| lower state | upper electronic state | breathing vibration | bending vibration | angular momentum | G=λ+l2-K | wavenumber cm−1[1] | wavelength Å | frequency THz | energy eV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2p2A2" | 3s2A1' | 0 | 0 | 16695 | 5990 | 500.5 | 2.069 | ||

| 3d2A" | 0 | 0 | 17297 | 5781 | 518.6 | 2.1446 | |||

| 3d2A1' | 0 | 0 | 17742 | 5636 | 531.9 | 2.1997 | |||

| 3p2E' | 1 | 1 | 18521 | 5399 | 555.2 | 2.2963 | |||

| 3p2A2" | 0 | 1 | 19451 | 5141.1 | 583.1 | 2.4116 | |||

| 3d2E' | 0 | 1 | 19542 | 5117 | 585.85 | 2.4229 | |||

| 3s2A1' | 1 | 0 | 19907 | 5023.39 | 596.8 | 2.46818 | |||

| 3p2E' | 0 | 3 | 19994 | 5001.58 | 599.48 | 2.47898 | |||

| 3d2E" | 1 | 0 | 20465 | 4886.4 | 613.524 | 2.5373 | |||

| 2s2A1' | 3p2E' | 14084 | 7100 | 422.2 | 1.746 | ||||

| 3p2A2" | band | 17857 | 5600 | 535 | 2.2 | ||||

| 3p2A2" Q branch | all superimposed | band | 17787 | 5622 | 533 | 2.205 |

The symmetric stretch vibration mode has a wave number of 3213.1 cm−1 for the 3s2A1' level and 3168 cm−1 for 3d2E" and 3254 cm−1 for 2p2A2".[1] The bending vibrational frequencies are also quite similar to those for H+

3.[1]

Levels

edit| electronic state | note | wavenumber cm−1[1] | frequency THz | energy eV | life ns [citation needed] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3d2A1' | 18511 | 554.95 | 2.2951 | 12.9 | |

| 3d2E" | 18409 | 551.89 | 2.2824 | 11.9 | |

| 3d2E' | 18037 | 540.73 | 2.2363 | 9.4 | |

| 3p2A2" | 17789 | 533.30 | 2.2055 | 41.3 4.1 | |

| 3s2A1' | 17600 | 527.638 | 2.1821 | 58.1 | |

| 3p2E' | 13961 | 418.54 | 1.7309 | 22.6 | |

| 2p2A2" | longest life | 993 | 29.76 | 0.12311 | 69700 |

| 2p2A2" | predissociation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21.8 |

| 2p2E' | dissociation | −16674 | −499.87 | −2.0673 | 0 |

Cation

editThe related H+

3 ion is the most prevalent molecular ion in interstellar space. It is believed to have played a crucial role in the cooling of early stars in the history of the Universe through its ability readily to absorb and emit photons.[9] One of the most important chemical reactions in interstellar space is H+

3 + e− → H3 and then → H2 + H.[6]

Calculations

editSince the molecule is relatively simple, researchers have attempted to calculate the properties of the molecule ab-initio from quantum theory. The Hartree–Fock equations have been used.[10]

Natural occurrence

editTriatomic hydrogen will be formed during the neutralization of H+

3. This ion will be neutralised in the presence of gasses other than He or H2, as it can abstract an electron. Thus H3 is formed in the aurora in the ionosphere of Jupiter and Saturn.[11]

History

editJ. J. Thomson observed H+

3 while experimenting with positive rays. He believed that it was an ionised form of H3 from about 1911. He believed that H3 was a stable molecule and wrote and lectured about it. He stated that the easiest way to make it was to target potassium hydroxide with cathode rays.[8] In 1913 Johannes Stark proposed that three hydrogen nuclei and electrons could form a stable ring shape. In 1919 Niels Bohr proposed a structure with three nuclei in a straight line, with three electrons orbiting in a circle around the central nucleus. He believed that H+

3 would be unstable, but that reacting H−

2 with H+ could yield neutral H3. Stanley Allen's structure was in the shape of a hexagon with alternating electrons and nuclei.[8]

In 1916 Arthur Dempster showed that H3 gas was unstable, but at the same time also confirmed that the cation existed. In 1917 Gerald Wendt and William Duane discovered that hydrogen gas subjected to alpha particles shrank in volume and thought that diatomic hydrogen was converted to triatomic.[8] After this researchers thought that active hydrogen could be the triatomic form.[8] Joseph Lévine went so far as to postulate that low pressure systems on the Earth happened due to triatomic hydrogen high in the atmosphere.[8] In 1920 Wendt and Landauer named the substance "Hyzone" in analogy to ozone and its extra reactivity over normal hydrogen.[12] Earlier Gottfried Wilhelm Osann believed he had discovered a form of hydrogen analogous to ozone which he called "Ozonwasserstoff". It was made by electrolysis of dilute sulfuric acid. In those days no one knew that ozone was triatomic so he did not announce triatomic hydrogen.[13] This was later shown to be a mixture with sulfur dioxide, and not a new form of hydrogen.[12]

In the 1930s active hydrogen was found to be hydrogen with hydrogen sulfide contamination, and scientists stopped believing in triatomic hydrogen.[8] Quantum mechanical calculations showed that neutral H3 was unstable but that ionised H+

3 could exist.[8] When the concept of isotopes came along, people such as Bohr then thought there may be an eka-hydrogen with atomic weight 3. This idea was later proven with the existence of tritium, but that was not the explanation of why molecular weight 3 was observed in mass spectrometers.[8] J. J. Thomson later believed that the molecular weight 3 molecule he observed was Hydrogen deuteride.[13] In the Orion nebula lines were observed that were attributed to nebulium which could have been the new element eka-hydrogen, especially when its atomic weight was calculated as near 3. Later this was shown to be ionised nitrogen and oxygen.[8]

Gerhard Herzberg was the first to actually observe the spectrum of neutral H3, and this triatomic molecule was the first to have a Rydberg spectrum measured where its own ground state was unstable.[1]

See also

edit- F. M. Devienne, one of the first to have studied the energy properties of Triatomic hydrogen

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lembo, L. J.; H. Helm; D. L. Huestis (1989). "Measurement of vibrational frequencies of the H3 molecule using two-step photoionization". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 90 (10): 5299. Bibcode:1989JChPh..90.5299L. doi:10.1063/1.456434. ISSN 0021-9606.

- ^ Binder, J.L.; Filby, E.A.; Grubb, A.C. (1930). "Triatomic Hydrogen". Nature. 126 (3166): 11–12. Bibcode:1930Natur.126...11B. doi:10.1038/126011c0. S2CID 4142737.

- ^ a b c d e Figger, H.; W. Ketterle; H. Walther (1989). "Spectroscopy of triatomic hydrogen". Zeitschrift für Physik D. 13 (2): 129–137. Bibcode:1989ZPhyD..13..129F. doi:10.1007/bf01398582. ISSN 0178-7683. S2CID 124478004.

- ^ Laperle, Christopher M; Jennifer E Mann; Todd G Clements; Robert E Continetti (2005). "Experimentally probing the three-body predissociation dynamics of the low-lying Rydberg states of H3 and D3". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 4 (1): 111–117. Bibcode:2005JPhCS...4..111L. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/4/1/015. ISSN 1742-6588.

- ^ a b c Helm H. et al.:of Bound States to Continuum States in Neutral Triatomic Hydrogen. in: Dissociative Recombination, ed. S. Guberman, Kluwer Academic, Plenum Publishers, USA, 275-288 (2003) ISBN 0-306-47765-3

- ^ a b Tashiro, Motomichi; Shigeki Kato (2002). "Quantum dynamics study on predissociation of H3 Rydberg states: Importance of indirect mechanism". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 117 (5): 2053. Bibcode:2002JChPh.117.2053T. doi:10.1063/1.1490918. hdl:2433/50519. ISSN 0021-9606.

- ^ Helm, Hanspeter (1988). "Measurement of the ionization potential of triatomic hydrogen". Physical Review A. 38 (7): 3425–3429. Bibcode:1988PhRvA..38.3425H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.38.3425. ISSN 0556-2791. PMID 9900777.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kragh, Helge (2010). "The childhood of H3 and H3+". Astronomy & Geophysics. 51 (6): 6.25–6.27. Bibcode:2010A&G....51f..25K. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4004.2010.51625.x. ISSN 1366-8781.

- ^ Shelley Littin (April 11, 2012). "H3+ The Molecule that Made the Universe". Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Defranceschi, M.; M. Suard; G. Berthier (1984). "Numerical solution of Hartree–Fock equations for a polyatomic molecule: Linear H3 in momentum space". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 25 (5): 863–867. doi:10.1002/qua.560250508. ISSN 0020-7608.

- ^ Keiling, Andreas; Donovan, Eric; Bagenal, Fran; Karlsson, Tomas (2013-05-09). Auroral Phenomenology and Magnetospheric Processes: Earth and Other Planets. John Wiley & Sons. p. 376. ISBN 978-1-118-67153-5. Retrieved 18 January 2014.

- ^ a b Wendt, Gerald L.; Landauer, Robert S. (1920). "Triatomic Hydrogen". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 42 (5): 930–946. doi:10.1021/ja01450a009.

- ^ a b Kragh, Helge (2011). "A Controversial Molecule: The Early History of Triatomic Hydrogen". Centaurus. 53 (4): 257–279. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.2011.00237.x. ISSN 0008-8994.

External links

edit- C. H. Green: "Rydberg states of Triatomic Hydrogen"

- The Elusive H3 Molecule GlusteeXD 2009 (humour)

- Ekesan, Solen; Kale, Seyit; Herzfeld, Judith (5 May 2014). "Transferable pseudoclassical electrons for aufbau of atomic ions". Journal of Computational Chemistry. 35 (15): 1159–1164. doi:10.1002/jcc.23612. PMC 4119322. PMID 24752384.

- Chakraborty, Romit; Mazziotti, David A. (5 October 2015). "Structure of the one-electron reduced density matrix from the generalized Pauli exclusion principle". International Journal of Quantum Chemistry. 115 (19): 1305–1310. doi:10.1002/qua.24934. The one-electron reduced density matrix convex set is pinned to the boundary of the pure N-representable set

- Saykally, Richard J. (2015). "Mid-IR laser action in the H3 Rydberg molecule and some possible astrophysical implications". AIP Conference Proceedings. 1642 (1642): 413–415. Bibcode:2015AIPC.1642..413S. doi:10.1063/1.4906707. S2CID 18158497. predicts H3 lasers may exist in the early universe