In Chinese philosophy, the three teachings (Chinese: 三教; pinyin: sān jiào; Vietnamese: tam giáo, Chữ Hán: 三教) are Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. The learning and the understanding of the three teachings are traditionally considered to be a harmonious aggregate within Chinese culture.[1] Literary references to the "three teachings" by prominent Chinese scholars date back to the 6th century.[1] The term may also refer to a non-religious philosophical grounds of aggregation as exemplified within traditional Chinese medicine.

Three teachings harmonious as one

editThe phrase also appears as the three teachings harmonious as one (三教合一; Sānjiào Héyī). In common understanding, three teachings harmonious as one simply reflects the long history, mutual influence, and (at times) complementary teachings of the three belief systems.[2]

It can also be used in reference to the "Sanyi teaching", a syncretic sect which was founded during the Ming dynasty by Lin Zhao'en, wherein Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist beliefs are combined according to their usefulness in self-cultivation.[3] However, the phrase is not necessarily a reference to this sect.

While Confucianism was the ideology of the law, the institutions and the ruling class, Taoism was the worldview of the radical intellectuals and it was also compatible with the spiritual beliefs of the peasants and the artisans. The two, although opposite ends of the philosophical spectrum, jointly created the Chinese "image of the world".[4]

The joint worship of the three teachings can be found in some Chinese temples, such as in Hanging Temple.

Sanjiao believers think that "[t]hree teachings are...safer than one" and that using elements from all three brings good fortune.[5]

Confucianism

editConfucianism is a complex school of thought, sometimes also referred to as a religion, revolving around the principles of the Chinese philosopher Confucius. It was developed in the Spring and Autumn period during the Zhou dynasty. The main concepts of this philosophy include ren (humaneness), yi (righteousness), li (propriety/etiquette), zhong (loyalty), and xiao (filial piety), along with strict adherence to social roles. This is illustrated through the five main relationships Confucius interpreted to be the core of society: ruler-subject, father-son, husband-wife, elder brother-younger brother, and friend-friend. In these bonds, the latter must pay respect to and serve the former, while the former is bound to care for the latter.[6][7]

The following quotation is from the Analects, a compilation of Confucius' sayings and teachings, written after his death by his disciples.

"The superior man has a dignified ease without pride. The mean man has pride without a dignified ease."

— Confucius, The Analects of Confucius[8]

This quotation exemplifies Confucius' idea of the junzi (君子) or gentleman. Originally this expression referred to "the son of a ruler", but Confucius redefined this concept to mean behaviour (in terms of ethics and values such as loyalty and righteousness) instead of mere social status.[6]

Taoism

editDaoism (or Taoism) is a philosophy centered on living in harmony with the Dao (Tao) (Chinese: 道; pinyin: Dào; lit. 'Way'), which is believed to be the source, pattern and substance of all matter.[9] Its origin can be traced back to the late 4th century B.C.E. and the main thinkers representative of this teaching are Laozi and Zhuang Zhou.[6] Key components of Daoism are Dao (the Way) and immortality, along with a stress on balance found throughout nature. There is less emphasis on extremes and instead focuses on the interdependence between things. For example, yin and yang (lit. 'dark and bright') do not exemplify the opposition of good against evil, but instead represents the interpenetration of mutually-dependent opposites present in everything; "within the Yang there exists the Yin and vice versa".[9]

The basis of Daoist philosophy is the idea of "wu wei", often translated as "non-action". In practice, it refers to an in-between state of "being, but not acting". This concept also overlaps with an idea in Confucianism as Confucius similarly believed that a perfect sage could rule without taking action. Daoism assumes any extreme action can initiate a counter-action of equal extremity, and so excessive government can become tyrannical and unjust, even when initiated with good intentions.[9]

The following is a quote from the Daodejing, one of the main texts in Daoist teachings:

"The truth is not always beautiful, nor beautiful words the truth."

— Laozi, Daodejing[10]

Buddhism

editBuddhism is a religion that is based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama. The main principles of this belief system are karma, rebirth, and impermanence. Buddhists believe that life is full of suffering, but that suffering can be overcome by attaining enlightenment. Nirvana (a state of perfect happiness) can be obtained by breaking away from (material) attachments and purifying the mind. However, different doctrines vary on the practices and paths followed in order to do so.[6]

Meditation serves as a significant part of practicing Buddhism. This calming and working of the mind helps Buddhists strive to become more peaceful and positive while developing wisdom through solving everyday problems. The negative mental states that are sought to be overcome are called "delusions", while the positive mental states are called "virtuous minds".[11]

Another concept prominent in the Buddhist belief system is the Eight-Fold Path. The Noble Eightfold Path is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths, which is said to be the first of all Buddha's teachings.[12] It stresses areas in life that can be explored and practice, such as right speech and right intention.[13]

Controversy

editThough the term "three teachings" is often focused on how well Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism have been able to coexist in harmony throughout Chinese history, evidence has shown that each practice has dominated, or risen to favour, during certain periods of time.[14] Emperors would choose to follow one specific system and the others were discriminated against, or tolerated at most. An example of this would be the Song dynasty, in which both Buddhism and Taoism became less popular. Neo-Confucianism (which had re-emerged during the previous Tang dynasty) was followed as the dominant philosophy.[15] A minority also claims that the phrase "three teachings" proposes that these mutually exclusive and fundamentally incomparable teachings are equal. This is a contested point of view as others stress that it is not so. Confucianism focuses on societal rules and moral values, whereas Taoism advocates simplicity and living happily while in tune with nature. On the other hand, Buddhism reiterates the ideas of suffering, impermanence of material items, and reincarnation while stressing the idea of reaching salvation beyond.[1]

See also

edit- Buddhist ethics

- Neo-Confucianism

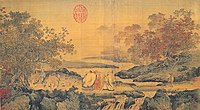

- Vinegar tasters – story about the leaders of the three teachings

- Three laughs at Tiger Brook

- Shinbutsu-shūgō (merger of Buddhism and Shinto)

- Caodaism (new religion based on the same three)

References

edit- ^ a b c "Living in the Chinese Cosmos: Understanding Religion in Late-Imperial China". afe.easia.columbia.edu.

- ^ Vuong, Quan-Hoang (2018). "Cultural additivity: behavioural insights from the interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in folktales". Palgrave Communications. 4 (1): 143. doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0189-2. S2CID 54444540.

- ^ Kirkland, Russell. "Lin Zhaoen (Lin Chao-en: 1517-1598)" (PDF). Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ Freiberg, J.W. “THE DIALECTIC OF CONFUCIANISM AND TAOISM IN ANCIENT CHINA.” Dialectical Anthropology 2, no. 3 (1977): 175–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/29789901.

- ^ Clayre, Alasdair (1985). The Heart of the Dragon (First American ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-395-35336-3.

- ^ a b c d Craig, Albert. The Heritage of Chinese Civilization. Pearson.

- ^ "Confucianism". Patheos. Retrieved 11 February 2015.

- ^ "The Analects Quotes". Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Chiu, Lisa. "Daoism in China". Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "Tao Te Ching Quotes". Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "What is Buddhism?". Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ Allan, John. "The Eight-Fold Path". Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ Nourie, Dana. "What is the Eightfold Path?". Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ "San Jiao / San Chiao / Three Teachings". Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ^ Theobald, Ulrich. "Chinese History - Song Dynasty 宋 (960-1279) literature, thought and philosophy". Retrieved 13 February 2015.