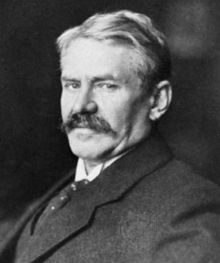

Ernst Peter Wilhelm Troeltsch (/trɛltʃ/;[1] German: [tʁœltʃ]; 17 February 1865 – 1 February 1923) was a German liberal Protestant theologian, a writer on the philosophy of religion and the philosophy of history, and a classical liberal politician. He was a member of the history of religions school. His work was a synthesis of a number of strands, drawing on Albrecht Ritschl, Max Weber's conception of sociology, and the Baden school of neo-Kantianism.

Ernst Troeltsch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 February 1865 |

| Died | 1 February 1923 |

| Alma mater | |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neo-Kantianism (Baden school) History of religions school Liberal Christianity Classical liberalism |

| Notable students | Gertrud von Le Fort Friedrich Gogarten |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Crisis of historicism Church, Sect, Mysticism |

Life

editTroeltsch was born on 17 February 1865 into a Lutheran family to a doctor but went to a Catholic school in a predominantly Catholic area. He then attended university, at the University of Erlangen and then at the University of Göttingen. During his university years, he experienced difficulties in his student fraternity as a result of his homosexuality.[2][3] His ordination in 1889 was followed in 1891 by a post teaching theology at Göttingen. In 1892, he moved on to teach at the University of Bonn. In 1894, he moved on again to Heidelberg University. Finally, in 1915, he transferred to teach at what is now the University of Berlin, where he took the title of professor of philosophy and civilization.[4] Troeltsch died on 1 February 1923. The famous church historian Adolf von Harnack preached at his funeral.[5]

Theology

editThroughout Troeltsch's life, he wrote frequently of his belief that changes in society posed a threat to Christian religion and that "the disenchantment of the world" as described by sociologist Max Weber was underway. At an academic conference that took place in 1896, after a paper on the doctrine of Logos, Troeltsch responded by saying, "Gentlemen, everything is tottering!"[6] Troeltsch also agreed with Weber's Protestant work ethic, restating it in his Protestantism and Progress. He viewed the creation of capitalism as having been the result of the specific Protestant sects named by Weber, rather than as a result of Protestantism as a whole. However, his analysis of Protestanitsm was more optimistic than Weber's in its focus on religious personal conviction as a source for individualism and spiritual mysticism as a source for subjectivism. Troeltsch interpreted non-Calvinist Protestantism as having had a positive effect on the development of the press, modern education systems, and politics.[7]

His most famous study, The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches (1912), is devoted to the vast reception history of Christian social precepts -- as they pertain to culture, economics, and institutions -- in the history of Western Civilization. Troeltsch's distinction between churches and sects as social types, for instance, set the course for further theological study.[8]

Troeltsch sought to explain the decline of religion in the modern era by studying the historical evolution of religion in society. He described European civilization as having three periods: ancient, medieval, and modern. Instead of claiming that modernity starts with the rise of Protestantism, Troeltsch argued that early Protestantism should be understood as a continuation of the medieval period. Therefore, the modern period starts later in his account: in the seventeenth century. The Renaissance in Italy and the scientific revolution planted the seeds for the arrival of the modern period. Protestantism delayed, rather than heralded, modernity. The reform movement around Luther, Troeltsch argued, was "in the first place, simply a modification of Catholicism, in which the Catholic formulation of the problems was retained, while a different answer was given to them."[9]

Troeltsch saw the distinction between early and late (or "neo-") Protestantism as "the presupposition for any historical understanding of Protestantism."[10]

Historiography

editTroeltsch developed three principles pertaining to critical historiography. Each of the principles served as a philosophical retort for preconceived notions. Troeltsch's principles (criticism, analogy, correlation) were used to account for historians' biases.[11]

Principle of criticism

editTroeltsch's claim in the principle concludes that absolutes within history cannot exist. Troeltsch surmised that judgments about the past must be varied. As such, the absolute truth of historical reality could not exist, but he claimed historical situation could be examined as more or less likely to have happened. For Troeltsch, finite and non-revisable historical claims are questionable.

Principle of analogy

editHistorians often think in analogies, which leads them to make anachronistic claims about the past. Troeltsch argued that the probability of analogies cannot usually be validated. He presented human nature as being fairly constant throughout time.

Principle of correlation

editIn regard to historical events, Troeltsch determined that humanity's historical life is interdependent upon each individual. Since the cumulative actions of individuals create historical events, there is a causal nature to all events that create an effect. Any radical event, the historian should assume, affected the historical nexus immediately surrounding that event. Troeltsch determines that in historical explanation, it is important to include antecedents and consequences of events in an effort to maintain historical events in their conditioned time and space.[12]

Politics

editTroeltsch was politically a classical liberal and served as a member of the Parliament of the Grand Duchy of Baden. In 1918, he joined the German Democratic Party (DDP). He strongly supported Germany's role in World War I: "Yesterday we took up arms. Listen to the ethos that resounds in the splendour of heroism: To your weapons, to your weapons!"[13]

Reception

editIn the immediate aftermath of Troeltsch's death, his work neglected as part of a wider rejection of liberal thought with the rise of neo-orthodoxy in Protestant theology, especially with the prominence of Karl Barth in the German-speaking world. From 1960 onwards, however, Troeltsch's thought has enjoyed a revival. Several books on Troeltsch's theological and sociological work have been published since 2000.[14]

References

edit- ^ Porter, Andrew P. (2001). By the Waters of Naturalism: Theology Perplexed among the Sciences. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock. p. 57. ISBN 1-57910-770-2.

- ^ Radkau, Joachim (2009). Max Weber: A Biography. Translated by Camiller, Patrick. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity. p. 578. ISBN 978-0-7456-4147-8. OCLC 232365644.

- ^ Graf, Friedrich Wilhelm (1982). "Polymorphes Gedächtnis: Zur Einführung in die Troeltsch-Nekrologie". In Graf, Friedrich Wilhelm; Nees, Christian (eds.). Ernst Troeltsch in Nachrufen. Troeltsch-Studien (in German). Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus. pp. 167–168. ISBN 978-3-579-00168-5.

- ^ Michael Walsh, ed. (2001). Dictionary of Christian Biography. Continuum. p. 1108. ISBN 0826452639.

- ^ Mikuteit, Johannes (1 January 2004). "Review of "Ernst Troeltsch in Nachrufen"". H-Soz-u-Kult. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

- ^ Robert J. Rubanowice (1982). Crisis in consciousness: The Thought of Ernst Troeltsch. Tallahassee: University Presses of Florida. p. 9. ISBN 0813007216.

- ^ Whimster, Sam (July 2005 – January 2006). "R.H. Tawney, Ernst Troeltsch and Max Weber on Puritanism and Capitalism". Max Weber Studies. 5–6 (2–1): 307–311. doi:10.1353/max.2006.a808955. ISSN 1470-8078. JSTOR 24581969. S2CID 147882750. Project MUSE 808955.

- ^ Schweiker, William (9 August 2007). Ernst Troeltsch's The Social Teaching of the Christian Churches. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199227228.003.0025.

- ^ Quoted in Rubanowice, p. 21, from Protestantism and Progress (translated by W. Montgomery, 1958), p. 59. Original title: Die Bedeutung des Protestantismus für die Entstehung de modernen Welt.

- ^ Quoted in Toshimasa Yasukata (1986). Ernst Troeltsch: Systematic Theologian of Radical Historicality. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press. p. 51. ISBN 1555400698.

- ^ Harvey, Van Austin (1966). The Historian and The Believer: The Morality of Historical Knowledge and Christian Faith. New York: Macmillan Company. pp. 13–15.

- ^ Troeltsch, Ernst. Gesammelte Schriften II. pp. 729–753.

- ^ Emma Wallis (9 April 2014). "Ernst Troeltsch and the power of the pen". DW.de. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Garrett E. Paul. "Why Troeltsch? Why today? Theology for the 21st Century". Religion-Online. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Sources

edit- Chapman, Mark. Ernst Troeltsch and Liberal Theology: Religion and Cultural Synthesis in Wilhelmine Germany (Oxford University Press 2002)

- Gerrish, B. A. (1975). Jesus, Myth, and History: Troeltsch's Stand in the "Christ-Myth" Debate. The Journal of Religion 55 (1): 13–35.

- Pauck, Wilhelm. Harnack and Troeltsch: Two historical theologians (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2015)

- Nix, Jr., Echol, Ernst Troeltsch and Comparative Theology (Peter Lang Publishing; 2010) 247 pages; a study of Troeltsch and the contemporary American philosopher and theologian Robert Neville (b. 1939).

- Norton, Robert E. The Crucible of German Democracy. Ernst Troeltsch and the First World War (Mohr Siebeck 2021).

- Troesltch, Ernst, "Historiography" in James Hastings (ed.), Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1914), VI, 716–723.

- Troeltsch, Ernst, "Protestantism and Progress," (Transaction Publishers, 2013) with an Introduction - "Protestantism and Progress, Redux," by Howard G. Schneiderman.

External links

edit- Ernst Troeltsch-Gesamtausgabe

- Troeltsch-Studien. Neue Folge

- Bill Fraatz. "Ernst Troeltsch (1865-1923)". Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology.