The Turkish invasion of Cyprus[26][a] began on 20 July 1974 and progressed in two phases over the following month. Taking place upon a background of intercommunal violence between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, and in response to a Greek junta-sponsored Cypriot coup d'état five days earlier, it led to the Turkish capture and occupation of the northern part of the island.[34]

| Turkish invasion of Cyprus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War and Cyprus problem | |||||||||

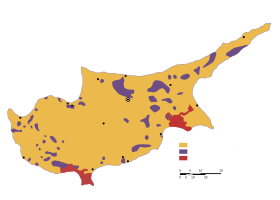

Ethnic map of Cyprus in 1973. Gold denotes Greek Cypriots, purple denotes Turkish Cypriot enclaves and red denotes British bases.[1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,500–3,500 casualties (estimated) (military and civilian)[9][18][19] including 568 KIA (498 TAF, 70 Resistance) 2,000 wounded[9] 270 civilians killed 803 civilians missing (official number in 1974)[20] |

4,500–6,000 casualties (estimated) (military and civilian)[9][18][19] including 309 (Cyprus) and 105 (Greece) military deaths[21][22][23] 1,000–1,100 missing (as of 2015)[24] | ||||||||

|

9 killed 65 wounded | |||||||||

The coup was ordered by the military junta in Greece and staged by the Cypriot National Guard[35][36] in conjunction with EOKA B. It deposed the Cypriot president Archbishop Makarios III and installed Nikos Sampson.[37][38] The aim of the coup was the union (enosis) of Cyprus with Greece,[39][40][41] and the Hellenic Republic of Cyprus to be declared.[42][43]

The Turkish forces landed in Cyprus on 20 July and captured 3% of the island before a ceasefire was declared. The Greek military junta collapsed and was replaced by a civilian government. Following the breakdown of peace talks, Turkish forces enlarged their original beachhead in August 1974 resulting in the capture of approximately 36% of the island. The ceasefire line from August 1974 became the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus and is commonly referred to as the Green Line.

Around 150,000 people (amounting to more than one-quarter of the total population of Cyprus, and to one-third of its Greek Cypriot population) were displaced from the northern part of the island, where Greek Cypriots had constituted 80% of the population. Over the course of the next year, roughly 60,000 Turkish Cypriots,[44] amounting to half the Turkish Cypriot population,[45] were displaced from the south to the north.[46] The Turkish invasion ended in the partition of Cyprus along the UN-monitored Green Line, which still divides Cyprus, and the formation of a de facto Autonomous Turkish Cypriot Administration in the north. In 1983, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) declared independence, although Turkey is the only country that recognises it.[47] The international community considers the TRNC's territory as Turkish-occupied territory of the Republic of Cyprus.[48] The occupation is viewed as illegal under international law, amounting to illegal occupation of European Union territory since Cyprus became a member.[49]

Background

editOttoman and British rule

editIn 1571 the mostly Greek-populated island of Cyprus was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, following the Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573). After 300 years of Ottoman rule the island and its population was leased to Britain by the Cyprus Convention, an agreement reached during the Congress of Berlin in 1878 between the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire. On 5 November 1914, in response to the Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War on the side of the Central Powers, the United Kingdom formally declared Cyprus (together with Egypt and Sudan) a protectorate of the British Empire[50] and later a Crown colony, known as British Cyprus. Article 20 of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 marked the end of the Turkish claim to the island.[50] Article 21 of the treaty gave Turkish nationals ordinarily resident in Cyprus the choice of leaving the island within 2 years or to remain as British subjects.[50]

At this time the population of Cyprus was composed of both Greeks and Turks, who identified themselves with their respective homeland.[51] However, the elites of both communities shared the belief that they were socially more progressive and better educated, and therefore distinct from the mainlanders.[citation needed] Greek and Turkish Cypriots lived quietly side by side for many years.[52]

Broadly, three main forces can be held responsible for transforming two ethnic communities into two national ones: education, British colonial practices, and insular religious teachings accompanying economic development.[citation needed] Formal education was perhaps the most important as it affected Cypriots during childhood and youth; education has been a main vehicle of transferring inter-communal hostility.[53]

British colonial policies, such as the principle of "divide and rule", promoted ethnic polarisation as a strategy to reduce the threat to colonial control.[54] For example, when Greek Cypriots rebelled in the 1950s, the Colonial Office expanded the size of the Auxiliary Police and in September 1955, established the Special Mobile Reserve which was made up exclusively of Turkish Cypriots, to combat EOKA.[55] This and similar practices contributed to inter-communal animosity.[citation needed]

Although economic development and increased education reduced the explicitly religious characteristics of the two communities, the growth of nationalism on the two mainlands increased the significance of other differences. Turkish nationalism was at the core of the revolutionary programme promoted by the father of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881–1938)[56] and affected Turkish Cypriots who followed his principles. President of the Republic of Turkey from 1923 to 1938, Atatürk attempted to build a new nation on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire and elaborated the programme of "six principles" (the "Six Arrows") to do so. [citation needed]

These principles of secularism (laicism) and nationalism reduced Islam's role in the everyday life of individuals and emphasised Turkish identity as the main source of nationalism. Traditional education with a religious foundation was discarded and replaced with one that followed secular principles and, shorn of Arab and Persian influences, was purely Turkish. Turkish Cypriots quickly adopted the secular programme of Turkish nationalism.[citation needed]

Under Ottoman rule Turkish Cypriots had been classified as Muslims, a distinction based on religion. Being thoroughly secular, Atatürk's programme made their Turkish identity paramount, and may have further reinforced their division from their Greek Cypriot neighbours.[citation needed]

1950s

editIn the early 1950s, a Greek nationalist group was formed called the Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston (EOKA, or "National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters").[57] Their objective was to drive the British out of the island first, and then to integrate the island with Greece. EOKA wished to remove all obstacles from their path to independence, or union with Greece.

The first secret talks for EOKA, as a nationalist organisation established to integrate the island with Greece, were started under the chairmanship of Archbishop Makarios III in Athens on 2 July 1952. In the aftermath of these meetings a "Council of Revolution" was established on 7 March 1953. In early 1954 secret weaponry shipments to Cyprus started with the knowledge of the Greek government. Lt. Georgios Grivas, formerly an officer in the Greek army, covertly disembarked on the island on 9 November 1954 and EOKA's campaign against the British forces began to grow.[58]

The first Turk to be killed by EOKA on 21 June 1955 was a policeman. EOKA also killed Greek Cypriot leftists.[59] After the September 1955 Istanbul Pogrom, EOKA started its activity against Turkish Cypriots.[60]

A year later EOKA revived its attempts to achieve the union of Cyprus with Greece. Turkish Cypriots were recruited into the police by the British forces to fight against Greek Cypriots, but EOKA initially did not want to open up a second front against Turkish Cypriots. However, in January 1957, EOKA forces began targeting and killing Turkish Cypriot police deliberately to provoke Turkish Cypriot riots in Nicosia, which diverted the British army's attention away from their positions in the mountains. In the riots, at least one Greek Cypriot was killed, which was presented by the Greek Cypriot leadership as an act of Turkish aggression.[61]

The Turkish Resistance Organisation (TMT, Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı) was formed initially as a local initiative to prevent the union with Greece which was viewed by Turkish Cypriots as an existential threat due to the exodus of Cretan Turks from Crete once the union with Greece was achieved. It was later supported and organised directly by the Turkish government,[62] and the TMT declared war on the Greek Cypriot rebels as well.[63][verification needed]

On 12 June 1958, eight Greek Cypriot men from Kondemenos village, who were arrested by the British police as part of an armed group suspected of preparing an attack against the Turkish Cypriot quarter of Skylloura, were killed by the TMT near the Turkish Cypriot populated village of Gönyeli, after being dropped off there by the British authorities.[64] TMT also blew up the offices of the Turkish press office in Nicosia in a false flag operation to attach blame to Greek Cypriots.[65][66] It also began a string of assassinations of prominent Turkish Cypriot supporters of independence.[63][66] The following year, after the conclusion of the independence agreements on Cyprus, the Turkish Navy sent a ship to Cyprus fully loaded with arms for the TMT. The ship was stopped and the crew was caught red-handed in the infamous "Deniz incident".[67]

1960–1963

editBritish rule lasted until the middle of August 1960,[68] when the island was declared an independent state on the basis of the London and Zürich Agreements of the previous year.

The 1960 Constitution of the Cyprus Republic proved unworkable, however, lasting only three years. Greek Cypriots wanted to end the separate Turkish Cypriot municipal councils permitted by the British in 1958, made subject to review under the 1960 agreements. For many Greek Cypriots these municipalities were the first stage on the way to the partition they feared. The Greek Cypriots wanted enosis, integration with Greece, while Turkish Cypriots wanted taksim, partition between Greece and Turkey.[69][citation needed]

Resentment also rose within the Greek Cypriot community because Turkish Cypriots had been given a larger share of governmental posts than the size of their population warranted. In accordance with the constitution 30% of civil service jobs were allocated to the Turkish community despite being only 18.3% of the population.[70] Additionally, the position of vice president was reserved for the Turkish population, and both the president and vice president were given veto power over crucial issues.[71]

1963–1974

editIn December 1963, the President of the Republic Makarios proposed thirteen constitutional amendments after the government was blocked by Turkish Cypriot legislators. Frustrated by these impasses and believing that the constitution prevented enosis,[72] the Greek Cypriot leadership believed that the rights given to Turkish Cypriots under the 1960 constitution were too extensive and had designed the Akritas plan, which was aimed at reforming the constitution in favour of Greek Cypriots, persuading the international community about the correctness of the changes and violently subjugating Turkish Cypriots in a few days should they not accept the plan.[73] The amendments would have involved the Turkish community giving up many of their protections as a minority, including adjusting ethnic quotas in the government and revoking the presidential and vice-presidential veto power.[71]

These amendments were rejected by the Turkish side and the Turkish representation left the government, although there is some dispute over whether they left in protest or were forced out by the National Guard. The 1960 constitution fell apart and communal violence erupted on 21 December 1963, when two Turkish Cypriots were killed at an incident involving the Greek Cypriot police.[73] Both President Makarios and Vice President Küçük issued calls for peace, but these were ignored. Greece, Turkey, and the UK – the guarantors of the Zürich and London Agreements that had led to Cyprus' independence – wanted to send a NATO force to the island under the command of General Peter Young.[citation needed]

Within a week of the violence flaring up, the Turkish army contingent had moved out of its barracks and seized the most strategic position on the island across the Nicosia–Kyrenia road,[citation needed] the historic jugular vein of the island. They retained control of that road until 1974, at which time it acted as a crucial link in Turkey's military invasion. From 1963 up to the point of the Turkish invasion of 20 July 1974, Greek Cypriots who wanted to use the road could only do so if accompanied by a UN convoy.[74]

700 Turkish residents of northern Nicosia, among them women and children, were taken hostage.[75] The violence resulted in the death of 364 Turkish and 174 Greek Cypriots,[76] destruction of 109 Turkish Cypriot or mixed villages and displacement of 25,000–30,000 Turkish Cypriots.[77] The British Daily Telegraph later called it an "anti Turkish pogrom".[78] A doomed truce was declared on 26 December 1963 and a British peacekeeping despatched to oversee it.[79]

In January 1964, negotiations were hosted by the British in London but their failure to make headway, and two vetoes thereafter by Makarios of a suggested NATO or NATO-dominated peacekeeping force, meant matters were turned over to the United Nations.[80] After intense debate, UN Security Council Resolution 186, unanimously adopted on 4 March, recommended the creation of a UN peacekeeping force (United Nations Force in Cyprus, UNFICYP) and the designation of a UN mediator.[81]

Violence by the militias of both sides had continued, and Turkey made several threats to invade. Indeed, Ankara had decided to do so when, in his famous letter of 5 June 1964, President Johnson of the United States warned that his country was against an invasion, making a veiled threat that NATO would not aid Turkey if its invasion of Cyprus led to a conflict with the Soviet Union.[82][83] More generally, although Resolution 186 had asked all countries to avoid interfering in Cypriot affairs, the United States disregarded this and, through persistent machinations, managed to overcome manoeuvring by Makarios and protests by the Soviet Union to intimately involve itself in negotiations in the form of presidential envoy Dean Acheson.[84] UN-mediated talks – invidiously assisted by Acheson, boycotted by Makarios because he correctly apprehended that the American goal was to terminate Cyprus' independence – began in July in Geneva.[85] Acheson dominated proceedings and, by the end of the month, the "Acheson Plan" had become the basis for all future negotiations.[86][87]

The crisis resulted in the end of the Turkish Cypriot involvement in the administration and their claiming that it had lost its legitimacy.[77] The nature of this event is still controversial: in some areas, Greek Cypriots prevented Turkish Cypriots from travelling and entering government buildings, while some Turkish Cypriots willingly refused to withdraw due to the calls of the Turkish Cypriot administration.[88] They started living in enclaves in different areas that were blockaded by the National Guard and were directly supported by Turkey. The republic's structure was changed unilaterally by Makarios and Nicosia was divided by the Green Line, with the deployment of UNFICYP troops.[77] In response to this, their movement and access to basic supplies became more restricted by Greek forces.[89]

Fighting broke out again in 1967, as the Turkish Cypriots pushed for more freedom of movement. Once again, the situation was not settled until Turkey threatened to invade on the basis that it would be protecting the Turkish population from ethnic cleansing by Greek Cypriot forces. To avoid that, a compromise was reached for Greece to be forced to remove some of its troops from the island; for Georgios Grivas, EOKA leader, to be forced to leave Cyprus and for the Cypriot government to lift some restrictions of movement and access to supplies of the Turkish populations.[90]

Cypriot military coup and Turkish invasion

editCypriot military coup of July 1974

editIn the spring of 1974, Greek Cypriot intelligence discovered that EOKA-B was planning a coup against President Makarios[91] which was sponsored by the military junta of Athens.[92]

The junta had come to power in 1967, via a military coup in Athens. In the autumn of 1973, after the student uprising on 17 November, there had been another coup in Athens, in which the original Greek junta had been replaced by one still more obscurantist, headed by the chief of Military Police, Dimitrios Ioannidis; though, the actual head was General Phaedon Gizikis. Ioannides believed that Makarios was no longer a true supporter of enosis, and suspected him of being a communist sympathiser.[92] This led Ioannides to support EOKA-B and the National Guard, as they tried to undermine Makarios.[93]

On 2 July 1974, Makarios wrote an open letter to President Gizikis complaining bluntly that 'cadres of the Greek military regime support and direct the activities of the 'EOKA-B' terrorist organisation'.[citation needed] He also ordered that Greece remove some 600 Greek officers in the Cypriot National Guard from Cyprus.[94] The Greek Government's immediate reply was to order the go-ahead of the coup. On 15 July 1974 sections of the Cypriot National Guard, led by its Greek officers, overthrew the government.[92]

Makarios narrowly escaped death in the attack. He fled the presidential palace from its back door and went to Paphos, where the British managed to retrieve him by Westland Whirlwind[citation needed] helicopter in the afternoon of 16 July and flew him from Akrotiri to Malta in a Royal Air Force Armstrong Whitworth Argosy transport aircraft and from there to London by de Havilland Comet the next morning.[92][95]

In the meantime, Nikos Sampson was declared provisional president of the new government. Sampson was an ultra-nationalist, pro-Enosis combatant who was known to be fanatically anti-Turkish and had taken part in violence against Turkish civilians in earlier conflicts.[92][96][page needed]

The Sampson regime took over radio stations and declared that Makarios had been killed;[92] but Makarios, safe in London, was soon able to counteract these reports.[97] The Turkish-Cypriots were not affected by the coup against Makarios; one of the reasons was that Ioannides did not want to provoke a Turkish reaction.[98][page needed]

In response to the coup, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger sent Joseph Sisco to try to mediate the conflict.[92] Turkey issued a list of demands to Greece via a US negotiator. These demands included the immediate removal of Nikos Sampson, the withdrawal of 650 Greek officers from the Cypriot National Guard, the admission of Turkish troops to protect their population, equal rights for both populations, and access to the sea from the northern coast for Turkish Cypriots.[99] Turkey, led by Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, then appealed to the UK as a signatory of the Treaty of Guarantee to take action to return Cyprus to its neutral status. The UK declined this offer, and refused to let Turkey use its bases on Cyprus as part of the operation.[100]

According to American diplomat James W. Spain, on the eve of the Turkish invasion US president Richard Nixon sent a letter to Bülent Ecevit that was not just reminiscent of Lyndon B. Johnson's letter to İsmet İnönü in the Cyprus crisis of 1963–64, but even harsher. However, Nixon's letter never reached the hands of the Turkish prime minister, and no one ever heard anything about it.[101]

First Turkish invasion, July 1974

editTurkey invaded Cyprus on Saturday, 20 July 1974. Heavily armed troops landed shortly before dawn at Kyrenia (Girne) on the northern coast meeting resistance from Greek and Greek Cypriot forces. Ankara said that it was invoking its right under the Treaty of Guarantee to protect the Turkish Cypriots and guarantee the independence of Cyprus.[102] By the time the UN Security Council was able to obtain a ceasefire on 22 July the Turkish forces were in command of a narrow path between Kyrenia and Nicosia, 3% of the territory of Cyprus,[103] which they succeeded in widening, violating the ceasefire demanded in Resolution 353.[104][105][106]

On 20 July, the 10,000 inhabitants of the Turkish Cypriot enclave of Limassol surrendered to the Cypriot National Guard. Following this, according to Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot eyewitness accounts, the Turkish Cypriot quarter was burned, women raped and children shot.[107][108] 1,300 Turkish Cypriots were confined in a prison camp afterwards.[109] The enclave in Famagusta was subjected to shelling and the Turkish Cypriot town of Lefka was occupied by Greek Cypriot troops.[110]

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, the prisoners of war taken at this stage and before the second invasion included 385 Greek Cypriots in Adana, 63 Greek Cypriots in the Saray Prison and 3,268 Turkish Cypriots in various camps in Cyprus.[111]

On the night of 21 to 22 July 1974, a battalion of Greek commandos was transported to Nicosia from Crete in a clandestine airlift operation.[35]

Collapse of the Greek junta and peace talks

editOn 23 July 1974 the Greek military junta collapsed mainly because of the events in Cyprus. Greek political leaders in exile started returning to the country. On 24 July 1974 Constantine Karamanlis returned from Paris and was sworn in as Prime Minister. He kept Greece from entering the war, an act that was highly criticised as an act of treason. Shortly after this Nikos Sampson renounced the presidency and Glafcos Clerides temporarily took the role of president.[112]

The first round of peace talks took place in Geneva, Switzerland between 25 and 30 July 1974, James Callaghan, the British Foreign Secretary, having summoned a conference of the three guarantor powers. There they issued a declaration that the Turkish occupation zone should not be extended, that the Turkish enclaves should immediately be evacuated by the Greeks, and that a further conference should be held at Geneva with the two Cypriot communities present to restore peace and re-establish constitutional government. In advance of this they made two observations, one upholding the 1960 constitution, the other appearing to abandon it. They called for the Turkish Vice-President to resume his functions, but they also noted 'the existence in practice of two autonomous administrations, that of the Greek Cypriot community and that of the Turkish Cypriot community'.

By the time that the second Geneva conference met on 14 August 1974, international sympathy (which had been with the Turks in their first attack) was swinging back towards Greece now that it had restored democracy. At the second round of peace talks, Turkey demanded that the Cypriot government accept its plan for a federal state, and population transfer.[113] When the Cypriot acting president Clerides asked for 36 to 48 hours in order to consult with Athens and with Greek Cypriot leaders, the Turkish Foreign Minister denied Clerides that opportunity on the grounds that Makarios and others would use it to play for more time.[114]

Second Turkish invasion, 14–16 August 1974

editThe Turkish Foreign Minister Turan Güneş had said to the Prime Minister Bülent Ecevit, "When I say 'Ayşe[b] should go on vacation' (Turkish: "Ayşe Tatile Çıksın"), it will mean that our armed forces are ready to go into action. Even if the telephone line is tapped, that would rouse no suspicion."[116] An hour and a half after the conference broke up, Turan Güneş called Ecevit and said the code phrase. On 14 August Turkey launched its "Second Peace Operation", which eventually resulted in the Turkish occupation of 37% of Cyprus. Turkish occupation reached as far south as the Louroujina Salient.

In the process, many Greek Cypriots became refugees. The number of refugees is estimated to be between 140,000 and 160,000.[117] The ceasefire line from 1974 separates the two communities on the island, and is commonly referred to as the Green Line.

After the conflict, Cypriot representatives and the United Nations consented to the transfer of the remainder of the 51,000 Turkish Cypriots that had not left their homes in the south to settle in the north, if they wished to do so.

The United Nations Security Council has challenged the legality of Turkey's action, because Article Four of the Treaty of Guarantee gives the right to guarantors to take action with the sole aim of re-establishing the state of affairs.[118] The aftermath of Turkey's invasion, however, did not safeguard the Republic's sovereignty and territorial integrity, but had the opposite effect: the de facto partition of the Republic and the creation of a separate political entity in the north. On 13 February 1975, Turkey declared the occupied areas of the Republic of Cyprus to be a "Federated Turkish State", to the universal condemnation of the international community (see United Nations Security Council Resolution 367).[119] The United Nations recognises the sovereignty of the Republic of Cyprus according to the terms of its independence in 1960. The conflict continues to affect Turkey's relations with Cyprus, Greece, and the European Union.

Human rights violations

editAgainst Greek Cypriots

editTurkey was found guilty by the European Commission of Human Rights for displacement of persons, deprivation of liberty, ill treatment, deprivation of life and deprivation of possessions.[120][121][122] The Turkish policy of violently forcing a third of the island's Greek population from their homes in the occupied North, preventing their return and settling Turks from mainland Turkey is considered an example of ethnic cleansing.[123][124]

In 1976 and again in 1983, the European Commission of Human Rights found Turkey guilty of repeated violations of the European Convention of Human Rights. Turkey has been condemned for preventing the return of Greek Cypriot refugees to their properties.[125] The European Commission of Human Rights reports of 1976 and 1983 state the following:

Having found violations of a number of Articles of the Convention, the Commission notes that the acts violating the Convention were exclusively directed against members of one of two communities in Cyprus, namely the Greek Cypriot community. It concludes by eleven votes to three that Turkey has thus failed to secure the rights and freedoms set forth in these Articles without discrimination on the grounds of ethnic origin, race, religion as required by Article 14 of the Convention.

Enclaved Greek Cypriots in the Karpass Peninsula in 1975 were subjected by the Turks to violations of their human rights so that by 2001 when the European Court of Human Rights found Turkey guilty of the violation of 14 articles of the European Convention of Human Rights in its judgement of Cyprus v Turkey (application no. 25781/94), less than 600 still remained. In the same judgement, Turkey was found guilty of violating the rights of the Turkish Cypriots by authorising the trial of civilians by a military court.[126][127]

The European commission of Human Rights with 12 votes against 1, accepted evidence from the Republic of Cyprus, concerning the rapes of various Greek-Cypriot women by Turkish soldiers and the torture of many Greek-Cypriot prisoners during the invasion of the island.[128][122] The high rate of rape reportedly resulted in the temporary permission of abortion in Cyprus by the conservative Cypriot Orthodox Church. [121][129][130] According to Paul Sant Cassia, rape was used systematically to "soften" resistance and clear civilian areas through fear. Many of the atrocities were seen as revenge for the atrocities against Turkish Cypriots in 1963–64 and the massacres during the first invasion.[131] It has been suggested that many of the atrocities were revenge killings, committed by Turkish Cypriot fighters in military uniform who might have been mistaken for Turkish soldiers.[132] In the Karpass Peninsula, a group of Turkish Cypriots reportedly chose young girls to rape and impregnated teenage girls. There were cases of rapes, which included gang rapes, of teenage girls by Turkish soldiers and Turkish Cypriot men in the peninsula, and one case involved the rape of an old Greek Cypriot man by a Turkish Cypriot. The man was reportedly identified by the victim and two other rapists were also arrested. Raped women were sometimes outcast from society.[133]

Against Turkish Cypriots

editDuring the Maratha, Santalaris and Aloda massacre by EOKA B, 126 people were killed on 14 August 1974.[134][135] The United Nations described the massacre as a crime against humanity, by saying "constituting a further crime against humanity committed by the Greek and Greek Cypriot gunmen."[136] In the Tochni massacre, 85 Turkish Cypriot inhabitants were massacred.[137]

The Washington Post covered another news of atrocity in which it is written that: "In a Greek raid on a small Turkish village near Limassol, 36 people out of a population of 200 were killed. The Greeks said that they had been given orders to kill the inhabitants of the Turkish villages before the Turkish forces arrived."[138][full citation needed]

In Limassol, upon the fall of the Turkish Cypriot enclave to the Cypriot National Guard, the Turkish Cypriot quarter was burned, women raped and children shot, according to Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot eyewitness accounts.[107][108] 1300 people were then led to a prison camp.[109]

Missing people

editThe missing persons list of the Republic of Cyprus confirms that 83 Turkish Cypriots disappeared in Tochni on 14 August 1974.[139] Also, as a result of the invasion, over 2000 Greek-Cypriot prisoners of war were taken to Turkey and detained in Turkish prisons. Some of them were not released and are still missing. In particular, the Committee on Missing Persons (CMP) in Cyprus, which operates under the auspices of the United Nations, is mandated to investigate approximately 1600 cases of Greek Cypriot and Greek missing persons.[140]

The issue of missing persons in Cyprus took a new turn in the summer of 2004 when the UN-sponsored Committee on Missing Persons (CMP)[141] began returning remains of identified missing individuals to their families. CMP designed and started to implement (from August 2006) its project on the Exhumation, Identification and Return of Remains of Missing Persons. The whole project is being implemented by bi-communal teams of Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriot scientists (archaeologists, anthropologists and geneticists) under the overall responsibility of the CMP. By the end of 2007, 57 individuals had been identified and their remains returned to their families.[citation needed]

Destruction of cultural heritage

editIn 1989, the government of Cyprus took an American art dealer to court for the return of four rare 6th-century Byzantine mosaics that survived an edict by the Byzantine Emperor, imposing the destruction of all images of sacred figures. Cyprus won the case, and the mosaics were eventually returned.[142] In October 1997, Aydın Dikmen, who had sold the mosaics, was arrested in Germany in a police raid and found to be in possession of a stash consisting of mosaics, frescoes and icons dating back to the 6th, 12th and 15th centuries, worth over $50 million. The mosaics, depicting Saints Thaddeus and Thomas, are two more sections from the apse of the Kanakaria Church, while the frescoes, including the Last Judgement and the Tree of Jesse, were taken off the north and south walls of the Monastery of Antiphonitis, built between the 12th and 15th centuries.[143] Frescoes found in possession of Dikmen included those from the 11th–12th century Church of Panagia Pergaminiotisa in Akanthou, which had been completely stripped of its ornate frescoes.[144]

According to a Greek Cypriot claim, since 1974, at least 55 churches have been converted into mosques and another 50 churches and monasteries have been converted into stables, stores, hostels, or museums, or have been demolished.[145] According to the government spokesman of the de facto Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, this has been done to keep the buildings from falling into ruin.[146]

In January 2011, the British singer Boy George returned an 18th-century icon of Christ to the Church of Cyprus that he had bought without knowing the origin. The icon, which had adorned his home for 26 years, had been looted from the church of St Charalampus from the village of New Chorio, near Kythrea, in 1974. The icon was noticed by church officials during a television interview of Boy George at his home. The church contacted the singer who agreed to return the icon at Saints Anargyroi Church, Highgate, north London.[147][148][149]

Opinions

editGreek Cypriot

editGreek Cypriots have claimed that the invasion and subsequent actions by Turkey have been diplomatic ploys, furthered by ultranationalist Turkish militants to justify expansionist Pan-Turkism. They have also criticised the perceived failure of Turkish intervention to achieve or justify its stated goals (protecting the sovereignty, integrity, and independence of the Republic of Cyprus), claiming that Turkey's intentions from the beginning were to create the state of Northern Cyprus.

Greek Cypriots condemn the brutality of the Turkish invasion, including but not limited to the high levels of rape, child rape and torture.[128] Greek Cypriots emphasise that in 1976 and 1983 Turkey was found guilty by the European Commission of Human Rights of repeated violations of the European Convention of Human Rights.[125]

Greek Cypriots have also claimed that the second wave of the Turkish invasion that occurred in August 1974, even after the Greek Junta had collapsed on 24 July 1974 and the democratic government of the Republic of Cyprus had been restored under Glafkos Clerides, did not constitute a justified intervention as had been the case with the first wave of the Turkish invasion that led to the Junta's collapse.

The stationing of 40,000 Turkish troops on Northern Cyprus after the invasion in violation of resolutions by the United Nations has also been criticised.

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 353, adopted unanimously on 20 July 1974, in response to the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, the Council demanded the immediate withdrawal of all foreign military personnel present in the Republic of Cyprus in contravention of paragraph 1 of the United Nations Charter.[150]

The United Nations Security Council Resolution 360 adopted on 16 August 1974 declared their respect for the sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity of the Republic of Cyprus, and formally recorded its disapproval of the unilateral military actions taken against it by Turkey.[151]

Turkish Cypriot

editTurkish Cypriot opinion quotes President Archbishop Makarios III, overthrown by the Greek Junta in the 1974 coup, who opposed immediate Enosis (union between Cyprus and Greece). Makarios described the coup which replaced him as "an invasion of Cyprus by Greece" in his speech to the UN security council and stated that there were "no prospects" of success in the talks aimed at resolving the situation between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, as long as the leaders of the coup, sponsored and supported by Greece, were in power.[152]

In Resolution 573, the Council of Europe supported the legality of the first wave of the Turkish invasion that occurred in July 1974, as per Article 4 of the Guarantee Treaty of 1960,[153][154] which allows Turkey, Greece, and the United Kingdom to unilaterally intervene militarily in failure of a multilateral response to crisis in Cyprus.[155]

Aftermath

editGreek Cypriots who were unhappy with the United States not stopping the Turkish invasion took part in protests and riots in front of the American embassy. Ambassador Rodger Davies was assassinated during the protests by a sniper from the extremist EOKA-B group.[156]

Declaration of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

editIn 1983 the Turkish Cypriot assembly declared independence of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Immediately upon this declaration Britain convened a meeting of the United Nations Security Council to condemn the declaration as "legally invalid". United Nations Security Council Resolution 541 (1983) considered the "attempt to create the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus is invalid, and will contribute to a worsening of the situation in Cyprus". It went on to state that it "considers the declaration referred to above as legally invalid and calls for its withdrawal".

In the following year UN resolution 550 (1984) condemned the "exchange of Ambassadors" between Turkey and the TRNC and went on to add that the Security Council "considers attempts to settle any part of Varosha by people other than its inhabitants as inadmissible and calls for the transfer of this area to the administration of the United Nations".[157]

Neither Turkey nor the TRNC have complied with the above resolutions and Varosha remains uninhabited.[157] In 2017, Varosha's beach was opened to be exclusively used by Turks (Turkish-Cypriots and Turkish nationals).[158]

On 22 July 2010, United Nations' International Court of Justice decided that "International law contains no prohibition on declarations of independence". In response to this non-legally-binding direction, German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle said it "has nothing to do with any other cases in the world" including Cyprus,[159] whereas some researchers stated the decision of ICJ provided the Turkish Cypriots an option to be used.[160][161]

Ongoing negotiations

editThe United Nations Security Council decisions for the immediate unconditional withdrawal of all foreign troops from Cyprus soil and the safe return of the refugees to their homes have not been implemented by Turkey and the TRNC.[162] Turkey and TRNC defend their position, stating that any such withdrawal would have led to a resumption of intercommunal fighting and killing.

In 1999, UNHCR halted its assistance activities for internally displaced persons in Cyprus.[163]

Negotiations to find a solution to the Cyprus problem have been taking place on and off since 1964. Between 1974 and 2002, the Turkish Cypriot side was seen by the international community as the side refusing a balanced solution. Since 2002, the situation has been reversed according to US and UK officials, and the Greek Cypriot side rejected a plan which would have called for the dissolution of the Republic of Cyprus without guarantees that the Turkish occupation forces would be removed. The latest Annan Plan to reunify the island which was endorsed by the United States, United Kingdom, and Turkey was accepted by a referendum by Turkish Cypriots but overwhelmingly rejected in parallel referendum by Greek Cypriots, after the Greek Cypriot Leadership and Greek Orthodox Church urged the Greek population to vote "no".[164]

Greek Cypriots rejected the UN settlement plan in an April 2004 referendum. On 24 April 2004, the Greek Cypriots rejected by a three-to-one margin the plan proposed by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan for the settlement of the Cyprus dispute. The plan, which was approved by a two-to-one margin by the Turkish Cypriots in a separate but simultaneous referendum, would have created a United Cyprus Republic and ensured that the entire island would reap the benefits of Cyprus's entry into the European Union on 1 May. The plan would have created a United Cyprus Republic consisting of a Greek Cypriot constituent state and a Turkish Cypriot constituent state linked by a federal government. More than half of the Greek Cypriots who were displaced in 1974 and their descendants would have had their properties returned to them and would have lived in them under Greek Cypriot administration within a period of 3.5 to 42 months after the entry into force of the settlement.[citation needed] For those whose property could not be returned, they would have received monetary compensation.[citation needed]

The entire island entered the EU on 1 May 2004 still divided, although the EU acquis communautaire – the body of common rights and obligations – applies only to the areas under direct government control, and is suspended in the areas occupied by the Turkish military and administered by Turkish Cypriots. However, individual Turkish Cypriots able to document their eligibility for Republic of Cyprus citizenship legally enjoy the same rights accorded to other citizens of European Union states.[citation needed] The Greek Cypriot government in Nicosia continues to oppose EU efforts to establish direct trade and economic links to TRNC as a way of encouraging the Turkish Cypriot community to continue to support the resolution of the Cyprus dispute.[citation needed]

Turkish settlers

editAs a result of the Turkish invasion, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe stated that the demographic structure of the island has been continuously modified as a result of the deliberate policies of the Turks. Following the occupation of Northern Cyprus, civilian settlers from Turkey began arriving on the island. Despite the lack of consensus on the exact figures, all parties concerned admitted that Turkish nationals began arriving in the northern part of the island in 1975.[165] It was suggested that over 120,000 settlers came to Cyprus from mainland Turkey.[165][dead link] This was a violation of the Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits an occupier from transferring or deporting parts of its own civilian population into an occupied territory.[166]

UN Resolution 1987/19 (1987) of the "Sub-Commission On Prevention Of Discrimination And Protection Of Minorities", which was adopted on 2 September 1987, demanded "the full restoration of all human rights to the whole population of Cyprus, including the freedom of movement, the freedom of settlement and the right to property" and also expressed "its concern also at the policy and practice of the implantation of settlers in the occupied territories of Cyprus which constitute a form of colonialism and attempt to change illegally the demographic structure of Cyprus."

In a report prepared by Mete Hatay on behalf of PRIO (Peace Research Institute Oslo), it was estimated that the number of Turkish mainlanders in the north who have been granted the right to vote is 37,000. This figure however excludes mainlanders who are married to Turkish Cypriots or adult children of mainland settlers as well as all minors. The report also estimates the number of Turkish mainlanders who have not been granted the right to vote, whom it labels as "transients", at a further 105,000.[167]

United States arms embargo on Turkey and Republic of Cyprus

editAfter the hostilities of 1974, the United States applied an arms embargo on both Turkey and Cyprus. The embargo on Turkey was lifted after three years by President Jimmy Carter, whereas the embargo on Cyprus remained in place for longer,[168] having most recently been enforced on 18 November 1992.[169] In December 2019, the US Congress lifted the decades-old arms embargo on Cyprus.[170] On 2 September 2020, United States decided to lift embargo on selling "non-lethal" military goods to Cyprus for one year starting from 1 October.[171] Each year USA decided to renew its decision (latest being September 2024), a move which was criticised heavily by Turkey. In August 2024, Cyprus and USA signed a defense cooperation agreement which will be valid over the next five years; Turkey also condemned this agreement.[172]

See also

edit- London and Zürich Agreements

- 1964 Battle of Tylliria

- 39th Infantry Division – the major Turkish unit in the invasion

- Cyprus Air Forces

- Cyprus Navy and Marine Police

- Greece–Turkey relations

- History of Cyprus (1878–present)

- List of modern conflicts in the Middle East

- List of wars between democracies

- Reported military losses during the Turkish invasion of Cyprus

- List of massacres in Cyprus

Footnotes

edit- ^ In Greek, the invasion is known as "Τουρκική εισβολή στην Κύπρο" (Tourkikí eisvolí stin Kýpro). Among Turkish speakers the operation is also referred as Cyprus Peace Operation (Kıbrıs Barış Harekâtı) or Operation Peace (Barış Harekâtı), based on the viewpoint that Turkey's military action constituted a peacekeeping operation. It is also referred to as Cyprus Operation (Kıbrıs Harekâtı)[27][28][29][30] and Cyprus Intervention (Kıbrıs Meselesi).[31] The operation was code-named by Turkey as Operation Atilla[32][33] (Turkish: Atilla Harekâtı).

- ^ Ayşe is a daughter of Turan Güneş, today Ayşe Güneş Ayata[115]

- ^ Map based on map from the CIA publication Atlas: Issues in the Middle East Archived 27 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, collected in Perry–Castañeda Library Map Collection at the University of Texas Libraries web cite.

- ^ Fortna, Virginia Page (2004). Peace Time: Cease-fire Agreements and the Durability of Peace. Princeton University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0691115122.

- ^ "Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Brussels – General Information". www.mfa.gov.cy. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ^ Juliet Pearse, "Troubled Northern Cyprus fights to keep afloat" in Cyprus. Grapheio Typou kai Plērophoriōn, Cyprus. Grapheion Dēmosiōn Plērophoriōn, Foreign Press on Cyprus, Public Information Office, 1979, p. 15. Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Joseph Weatherby, The other world: Issues and Politics of the Developing World, Longman, 2000, ISBN 978-0-8013-3266-1, p. 285. Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tocci, Nathalie (2007). The EU and Conflict Resolution: Promoting Peace in the Backyard. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1134123384.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew (2000). Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 2. ISBN 978-0275965334.

- ^ Michael, Michális Stavrou (2011). Resolving the Cyprus Conflict: Negotiating History. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 130. ISBN 978-1137016270.

- ^ a b c d Pierpaoli, Paul G. Jr. (2014). Hall, Richard C. (ed.). War in the Balkans: An Encyclopedic History from the Fall of the Ottoman Empire to the Breakup of Yugoslavia. ABC-Clio. pp. 88–90. ISBN 978-1-61069-031-7.

As a result of the Turkish invasion and occupation, perhaps as many as 200,000 Greeks living in northern Cyprus fled their homes and became refugees in the south. It is estimated that 638 Turkish troops died in the fighting, with another 2,000 wounded. Another 1,000 or so Turkish civilians were killed or wounded. Cypriot Greeks, together with Greek soldiers dispatched to the island, suffered 4,500–6,000 killed or wounded, and 2,000–3,000 more missing.

- ^ Katholieke Universiteit Brussel, 2004 Archived 17 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine "Euromosaic III: Presence of Regional and Minority Language Groups in the New Member States", p. 18

- ^ Smit, Anneke (2012). The Property Rights of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: Beyond Restitution. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-0415579605.

- ^ Thekla Kyritsi, Nikos Christofis (2018). Cypriot Nationalisms in Context: History, Identity and Politics. p. 12.

- ^ Keser, Ulvi (2006). Turkish-Greek Hurricane on Cyprus (1940 – 1950 – 1960 – 1970), 528. sayfa, Publisher: Boğaziçi Yayınları, ISBN 975-451-220-5.

- ^ Η Μάχη της Κύπρου, Γεώργιος Σέργης, Εκδόσεις Αφοι Βλάσση, Αθήνα 1999, p. 253 (in Greek)

- ^ Η Μάχη της Κύπρου, Γεώργιος Σέργης, Εκδόσεις Αφοι Βλάσση, Αθήνα 1999, p. 254 (in Greek)

- ^ Η Μάχη της Κύπρου, Γεώργιος Σέργης, Εκδόσεις Αφοι Βλάσση, Αθήνα 1999, p. 260 (in Greek)

- ^ Administrator. "ΕΛ.ΔΥ.Κ '74 – Χρονικό Μαχών". eldyk74.gr. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ a b Jentleson, Bruce W.; Thomas G. Paterson; Council on Foreign Relations (1997). Encyclopedia of US foreign relations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511059-3.

Greek/Greek Cypriot casualties were estimated at 6,000 and Turkish/Turkish Cypriot casualties at 3,500, including 1,500 dead...

- ^ a b Tony Jaques (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-First Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-313-33538-9.

The invasion cost about 6,000 Greek Cypriot and 1500–3500 Turkish casualties (20 July 1974)

- ^ Haydar Çakmak: Türk dış politikası, 1919–2008, Platin, 2008, ISBN 9944137251, p. 688 (in Turkish); excerpt from reference: 415 ground, 65 navy, 10 air, 13 gendarmerie, 70 resistance (= 568 killed)

- ^ Erickson & Uyar 2020, p. 209

- ^ Hatziantoniou 2007, p. 557

- ^ Καταλόγοι Ελληνοκυπρίων και Ελλαδιτών φονευθέντων κατά το Πραξικόπημα και την Τουρκική Εισβολή (in Greek). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Cyprus. Archived from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Figures and Statistics of Missing Persons" (PDF). Committee on Missing Persons in Cyprus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ UNFICYP report, found in Γεώργιος Τσουμής, Ενθυμήματα & Τεκμήρια Πληροφοριών της ΚΥΠ, Δούρειος Ίππος, Athens November 2011, Appendix 19, p. 290

- ^ Vincent Morelli (2011). Cyprus: Reunification Proving Elusive. Diane Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4379-8040-0.

The Greek Cypriots and much of the international community refer to it as an "invasion.

- ^ Mirbagheri, Farid (2010). Historical dictionary of Cyprus ([Online-Ausg.] ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0810862982.

- ^ Kissane, Bill (2014). After Civil War: Division, Reconstruction, and Reconciliation in Contemporary Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-8122-9030-1.

were incorporated in the Greek Cypriot armed forces, gave Turkey reason and a pretext to invade Cyprus, claiming its role under the Treaty of Guarantees.

- ^ A. C. Chrysafi (2003). Who Shall Govern Cyprus – Brussels Or Nicosia?. Evandia Publishing UK Limited. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-904578-00-0.

On 20 July 1974, Turkey invaded Cyprus under the pretext of protecting the Turkish-Cypriot minority.

- ^ Robert B. Kaplan; Richard B. Baldauf Jr.; Nkonko Kamwangamalu (2016). Language Planning in Europe: Cyprus, Iceland and Luxembourg. Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-134-91667-2.

Five days later, on 20 July 1974, Turkey, claiming a right to intervene as one of the guarantors of the 1960 agreement, invaded the island on the pretext of restoring the constitutional order of the Republic of Cyprus.

- ^ Arıcıoğlu, Ece Buket (26 June 2023). "Kıbrıs Meselesi Ekseninde 1974 Kıbrıs Müdahalesi" [The 1974 Cyprus Intervention in the Context of the Cyprus Issue]. Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal ve Teknik Araştırmalar Dergisi (in Turkish) (21): 103–115. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Rongxing Guo, (2006), Territorial Disputes and Resource Management: A Global Handbook. p. 91

- ^ Angelos Sepos, (2006), The Europeanization of Cyprus: Polity, Policies and Politics, p. 106

- ^ Uzer, Umut (2011). Identity and Turkish Foreign Policy: The Kemalist Influence in Cyprus and the Caucasus. I.B. Tauris. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-1848855694.

- ^ a b Solanakis, Mihail. "Operation "Niki" 1974: A suicide mission to Cyprus". Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "U.S. Library of Congress – Country Studies – Cyprus – Intercommunal Violence". Countrystudies.us. 21 December 1963. Archived from the original on 24 August 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ^ Mallinson, William (2005). Cyprus: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8.

- ^ BBC: Turkey urges fresh Cyprus talks Archived 27 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine (2006-01-24)

- ^ Papadakis, Yiannis (2003). "Nation, narrative and commemoration: political ritual in divided Cyprus". History and Anthropology. 14 (3): 253–270. doi:10.1080/0275720032000136642. S2CID 143231403.

[...] culminating in the 1974 coup aimed at the annexation of Cyprus to Greece

- ^ Atkin, Nicholas; Biddiss, Michael; Tallett, Frank (2011). The Wiley-Blackwell Dictionary of Modern European History Since 1789. John Wiley & Sons. p. 184. ISBN 978-1444390728.

- ^ Journal of international law and practice, Volume 5. Detroit College of Law at Michigan State University. 1996. p. 204.

- ^ Strategic review, Volume 5 (1977), United States Strategic Institute, p. 48 Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Allcock, John B. Border and territorial disputes (1992), Longman Group, p. 55 Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Tocci 2007, 32.

- ^ Pericleous, Chrysostomos (2009). Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan. I.B. Tauris. p. 201. ISBN 978-0857711939.

- ^ "1974: Turkey Invades Cyprus". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ Salin, Ibrahm (2004). Cyprus: Ethnic Political Components. Oxford: University Press of America. p. 29.

- ^ Quigley (2010). The Statehood of Palestine. Cambridge University Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-139-49124-2.

The international community found this declaration invalid, on the ground that Turkey had occupied territory belonging to Cyprus and that the putative state was therefore an infringement on Cypriot sovereignty.

- ^ James Ker-Lindsay; Hubert Faustmann; Fiona Mullen (2011). An Island in Europe: The EU and the Transformation of Cyprus. I.B. Tauris. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-84885-678-3.

Classified as illegal under international law, the occupation of the northern part leads automatically to an illegal occupation of EU territory since Cyprus' accession.

- ^ a b c "Treaty of Lausanne". byu.edu. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2011.

- ^ Uzer, Umut (2011). Identity and Turkish Foreign Policy: The Kemalist Influence in Cyprus and the Caucasus. I.B. Tauris. pp. 112–113. ISBN 978-1848855694.

- ^ Smith, M. "Explaining Partition: Reconsidering the role of the security dilemma in the Cyprus crisis of 1974." Diss. University of New Hampshire, 2009. ProQuest 15 October 2010, 52

- ^ Sedat Laciner, Mehmet Ozcan and Ihsan Bal, USAK Yearbook of International Politics and Law, USAK Books, 2008, p. 444. Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Vassilis Fouskas, Heinz A. Richter, Cyprus and Europe: The Long Way Back, Bibliopolis, 2003, pp. 77, 81, 164. Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James S. Corum, Bad Strategies: How Major Powers Fail in Counterinsurgency, Zenith Imprint, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7603-3080-7, pp. 109–110. Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cyprus Dimension of Turkish Foreign Policy Archived 7 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, by Mehmet Fatih Öztarsu (Strategic Outlook, 2011)

- ^ The Cyprus Revolt: An Account of the Struggle for Union with Greece Archived 24 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, by Nancy Crawshaw (London: George Allen and Unwin, 1978), pp. 114–129.

- ^ It-Serve. "A Snapshot of Active Service in 'A' Company Cyprus 1958–59". The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Princess Louise's). Archived from the original on 19 October 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E., eds. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 279. ISBN 978-1576079195.

- ^ Λιμπιτσιούνη, Ανθή Γ. "Το πλέγμα των ελληνοτουρκικών σχέσεων και η ελληνική μειονότητα στην Τουρκία, οι Έλληνες της Κωνσταντινούπολης της Ίμβρου και της Τενέδου" (PDF). University of Thessaloniki. p. 56. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 January 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ French, David (2015). Fighting EOKA: The British Counter-Insurgency Campaign on Cyprus, 1955–1959. Oxford University Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0191045592.

- ^ Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0230392069.

- ^ a b Roni Alasor, Sifreli Mesaj: "Trene bindir!", ISBN 960-03-3260-6 [page needed]

- ^ The Outbreak of Communal Strife, 1958 Archived 11 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, London.

- ^ "Denktaş'tan şok açıklama". Milliyet (in Turkish). 9 January 1995. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ a b Arif Hasan Tahsin, The rise of Dektash to power, ISBN 9963-7738-3-4 [page needed]

- ^ "The Divisive Problem of the Municipalities". Cyprus-conflict.net. Archived from the original on 25 November 2002. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ O'Malley & Craig 1999, p. 77.

- ^ "The Poisons of Cyprus". The New York Times. 19 February 1964. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- ^ Cyprus: A Country Study" U.S Library of Congress. Ed. Eric Solsten. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991. Web. 1 October 2010

- ^ a b Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport: Praeger. 2000. 47

- ^ Reynolds, Douglas (2012). Turkey, Greece, and the Borders of Europe. Images of Nations in the West German Press 1950–1975. Frank & Timme GmbH. p. 91. ISBN 978-3865964410.

- ^ a b Eric Solsten, ed. Cyprus: A Country Study Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1991.

- ^ Henn, Francis (2004). A Business of Some Heat: The United Nations Force in Cyprus Before and During the 1974 Turkish Invasion. Casemate Publisher. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-1844150816.

- ^ Keith Kyle (1997). Cyprus: in search of peace. MRG. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-897693-91-9.

- ^ Oberling, Pierre. The Road to Bellapais (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 120 Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine: "According to official records, 364 Turkish Cypriots and 174 Greek Cypriots were killed during the 1963–1964 crisis."

- ^ a b c Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal aspects of the Cyprus problem: Annan Plan and EU accession. E Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-90-04-15223-6.

- ^ Telegraph View (represents the editorial opinion of The Daily Telegraph and The Sunday Telegraph) (30 April 2007). "Turkish distractions". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

we called for intervention in Cyprus when the anti-Turkish pogroms began in the 1960s

- ^ Brinkley 1992, p. 211–2.

- ^ Bolukbasi 1993, p. 513.

The London Conference was attended by the Greek and Turkish foreign ministers, the British Secretary of State for Commonwealth Affairs, and Greek- and Turkish-Cypriot representatives. - ^ Varnava 2020, p. 18.

- ^ Bokulasi.

- ^ Bahcheli, Tazun. Cyprus in the Politics of Turkey since 1955, in: Norma Salem (ed). Cyprus: A Regional Conflict and its Resolution. London: The Macmillan Press Ltd, 1992, 62–71. 65

- ^ Brinkley 1992, pp. 213–5.

- ^ Brinkley 1992, pp. 214–5.

- ^ Brinkley 1992, p. 215.

- ^ Pericleous, Chrysostoms. "The Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan." London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd. 2009. pp. 84–89, 105–107

- ^ Ker-Lindsay, James (2011). The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0199757169.

- ^ Oberling, Pierre. The Road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to Northern Cyprus. New York: Columbia University Press. 1982, 58 [ISBN missing]

- ^ Pericleous, Chrysostoms. "The Cyprus Referendum: A Divided Island and the Challenge of the Annan Plan." London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd. 2009. p. 101

- ^ "Makarios writes General Ghizikis". Cyprus-conflict.net. July 1974. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Cyprus: Big Troubles over a Small Island". Time. 29 July 1974. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008.

- ^ "Cyprus: A Country Study" U.S Library of Congress. Ed. Eric Solsten. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991. Web. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew. "The Mediterranean Feud", New York: Praeger Publishers, 1983, 98.

- ^ Constandinos, Andreas (2009). America, Britain and the Cyprus Crisis of 1974: Calculated Conspiracy Or Foreign Policy Failure?. AuthorHouse. p. 206. ISBN 978-1467887076.

- ^ Oberling, Pierre. The Road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to Northern Cyprus. New York: Columbia University Press. 1982.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew. "The Mediterranean Feud". New York: Praeger Publishers, 1983, p. 99

- ^ The Tragic Duel and the Betrayal of Cyprus by Marios Adamides, 2012

- ^ Dodd, Clement. "The History and Politics of the Cyprus Conflict." New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2010, 113.

- ^ Kassimeris, Christos. "Greek Response to the Cyprus Invasion" Small Wars and Insurgencies 19.2 (2008): 256–273. EBSCOhost 28 September 2010. 258

- ^ Katsoulas, Spyros (2021). "The “Nixon Letter” to Ecevit: An Untold Story of the Eve of the Turkish Invasion of Cyprus in 1974", The International History Review, https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2021.1935293 Archived 13 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kassimeris, Christos. "Greek Response to the Cyprus Invasion" Small Wars and Insurgencies 19.2 (2008): 256–273. EBSCOhost 28 September 2010, 258.

- ^ "Η Τουρκική Εισβολή στην Κύπρο". Sansimera.gr. Archived from the original on 20 July 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

Σ' αυτό το χρονικό σημείο, οι Τούρκοι ελέγχουν το 3% του Κυπριακού εδάφους, έχοντας δημιουργήσει ένα προγεφύρωμα, που συνδέει την Κερύνεια με τον τουρκοκυπριακό θύλακο της Λευκωσίας. (At this point in time, the Turks control 3% of Cypriot territory, having created a bridgehead connecting Kyrenia with the Turkish Cypriot enclave in Nicosia.)

- ^ Mehmet Ali Birand, "30 sıcak gün", March 1976

- ^ Minority Rights Group Report. Vol. 1–49. The Group. 1983. p. 130. ISBN 978-0903114011.

The crisis of 1974: The Turkish assault and occupation Cyprus: In Search of Peace: The Turkish ... UN was able to obtain a ceasefire on 22 July the Turkish Army had only secured a narrow corridor between Kyrenia and Nicosia, which it widened during the next few days in violation of the terms, but which it was impatient to expand further on military as well as political grounds.

- ^ Horace Phillips (1995). Envoy Extraordinary: A Most Unlikely Ambassador. The Radcliffe Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-85043-964-6.

Troops landed around Kyrenia, the main town on that coast, and quickly secured a narrow bridgehead.

- ^ a b Facts on File Yearbook 1974. Facts on File. 1975. p. 590. ISBN 978-0871960337.

- ^ a b Oberling, Pierre (1982). The Road to Bellapais: The Turkish Cypriot Exodus to Northern Cyprus. Boulder: Social Science Monographs. pp. 164–165. ISBN 978-0880330008.

[...] children were shot in the street and the Turkish quarter of Limassol was burnt out by the National Guard.

- ^ a b Higgins, Rosalyn (1969). United Nations Peacekeeping: Europe, 1946–1979. Oxford University Press. p. 375. ISBN 978-0192183224.

- ^ Karpat, Kemal (1975). Turkey's Foreign Policy in Transition: 1950–1974. Brill. p. 201. ISBN 978-9004043237.

- ^ Dinstein, Yoram; Domb, Fania, eds. (1999). Israel Yearbook on Human Rights 1998. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-9041112958.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew. Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport: Praeger. 2000, 89.

- ^ Dodd, Clement. "The History and Politics of the Cyprus Conflict." New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2010, 119

- ^ "Cyprus: A Country Study" U.S Library of Congress. Ed. Eric Solsten. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1991. Web. 1 October 2010.

- ^ Alper Sedat Aslandaş & Baskın Bıçakçı, Popüler Siyasî Deyimler Sözlüğü, İletişim Yayınları, 1995, ISBN 975-470-510-0, p. 34.

- ^ Jan Asmussen, Cyprus at war: Diplomacy and Conflict during the 1974 Crisis, I.B. Tauris, 2008, ISBN 978-1-84511-742-9, p. 191.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew (2000). Cyprus: A Troubled Island. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-275-96533-4.

- ^ "Press and Information office (Cyprus)". Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-21. Retrieved 19 September 2012 via Web Archive

- ^ "Security Resolution 367" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ European Commission of Human Rights, "Report of the Commission to Applications 6780/74 and 6950/75", Council of Europe, 1976, pp. 160–163., Link from Internet Archive

- ^ a b "Cyprus v. Turkey - HUDOC". ECHR. Archived from the original on 24 April 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ a b "APPLICATIONS/REQUÉTES N° 6780/74 6 N° 6950/75 CYPRUS v/TURKEY CHYPRE c/TURQUI E" (PDF). Government of Cyprus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- ^ Borowiec, Andrew (2000). Cyprus: a troubled island. New York: Praeger. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-275-96533-4.

- William Mallinson, Bill Mallinson, Cyprus: a modern history, I.B. Tauris, 2005, ISBN 978-1-85043-580-8, p. 147

- Carpenter, Ted Galen (2002). Peace and Freedom: Foreign Policy for a Constitutional Republic. Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-930865-34-1.

- Linos-Alexandre Sicilianos (2001). The Prevention of Human Rights Violations (International Studies in Human Rights). Berlin: Springer. p. 24. ISBN 978-90-411-1672-7.

- Rezun, Miron (2001). Europe's nightmare: the struggle for Kosovo. New York: Praeger. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-275-97072-7.

- Antony Evelyn Alcock, A history of the protection of regional cultural minorities in Europe: from the Edict of Nantes to the present day, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, ISBN 978-0-312-23556-7, p. 207

- ^ "Reuniting Cyprus?". jacobinmag.com. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b "JUDGEMENT IN THE CASE OF CYPRUS v. TURKEY 1974–1976". Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- ^ "Despite ruling, Turkey won't pay damages to Cyprus – Middle East Institute". www.mei.edu. Archived from the original on 1 September 2016. Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- ^ "ECtHR –Cyprus v. Turkey , Application no. 25781/94, 10 May 2001 | European Database of Asylum Law". European Database of Asylum Law. Archived from the original on 29 April 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ a b European Commission of Human Rights, "Report of the Commission to Applications 6780/74 and 6950/75", Council of Europe, 1976, p. 120,124. Archived 12 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Link from Internet Archive

- ^ Grewal, Inderpal (1994). Scattered Hegemonies: Postmodernity and Transnational Feminist Practices. University of Minnesota Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0816621385.

- ^ Emilianides, Achilles C.; Aimilianidēs, Achilleus K. (2011). Religion and Law in Cyprus. Kluwer Law International. p. 179. ISBN 978-9041134387.

- ^ Cassia, Paul Sant (2007). Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus. Berghahn Books, Incorporated. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-84545-228-5.

- ^ Bryant, Rebecca (22 March 2012). "Partitions of Memory: Wounds and Witnessing in Cyprus" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 54 (2): 335. doi:10.1017/S0010417512000060. S2CID 145424577. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2019.

- ^ Uludağ, Sevgül. "Turkish Cypriot and Greek Cypriot victims of rape: The invisible pain and trauma that's kept 'hidden'". Hamamböcüleri Journal. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Oberling, Pierre. The road to Bellapais: the Turkish Cypriot exodus to northern Cyprus Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine (1982), Social Science Monographs, p. 185

- ^ Paul Sant Cassia, Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus, Berghahn Books, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84545-228-5, p. 237 Archived 7 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ UN monthly chronicle, Volume 11 (1974), United Nations, Office of Public Information, p. 98 Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paul Sant Cassia, Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory, and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus, Berghahn Books, 2007; ISBN 978-1-84545-228-5, Massacre&f=false p. 61 Archived 22 January 2023 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Washington Post, 23 July 1974.

- ^ List of Turkish Cypriot missing persons Archived 15 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Cyprus) Retrieved on 2 March 2012.

- ^ Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Washington Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine (Embassy of the Republic of Cyprus in Washington) Retrieved on 11 November 2012.

- ^ "Committee on Missing Persons (CMP)". Cmp-cyprus.org. Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- ^ Bourloyannis, Christiane; Virginia Morris (January 1992). "Autocephalous Greek-Orthodox Church of Cyrprus v. Goldberg & Feldman Fine Arts, Inc". The American Journal of International Law. 86 (1): 128–133. doi:10.2307/2203143. JSTOR 2203143. S2CID 147162639.

- ^ Morris, Chris (18 January 2002). "Shame of Cyprus's looted churches". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 March 2004. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ Bağışkan, Tuncer (18 May 2013). "Akatu (Tatlısu) ile çevresinin tarihi geçmişi…" (in Turkish). Yeni Düzen. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ "Cyprusnet". Cyprusnet. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ "Cyprus: Portrait of a Christianity Obliterated" (in Italian). Chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it. Archived from the original on 4 November 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ Boy George returns lost icon to Cyprus church Archived 28 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine Guardian.co.uk, 20 January 2011.

- ^ Boy George returns Christ icon to Cyprus church Archived 3 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine BBC.co.uk, 19 January 2011.

- ^ Representation of the Church of Cyprus to the European Union, The post-byzantine icon of Jesus Christ returns to the Church of Cyprus London Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, January 2011.

- ^ "United Nations Official Document". www.un.org. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ^ "Security Council Resolution 360 – UNSCR". unscr.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ^ "Cyprus History: Archbishop Makarios on the invasion of Cyprus by Greece". Cypnet.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 November 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ "Resolution 573 (1974)". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014.

Regretting the failure of the attempt to reach a diplomatic settlement which led the Turkish Government to exercise its right of intervention in accordance with Article 4 of the Guarantee Treaty of 1960.

- ^ Council of Europe,Resolution 573 (29 July 1974) Archived 12 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. "The legality of the Turkish intervention on Cyprus has also been underlined by the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe in its resolution 573 (1974), adopted on 29 July 1974."

- ^ "IV". . Cyprus. 1960 – via Wikisource.

In so far as common or concerted action may not prove possible, each the three guaranteeing Powers reserves the right to take action with the sole aim of re-establishing the state of affairs created by the present Treaty.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ I.B. Tauris & Co. 2000, Brendan O’Malley: The Cyprus Conspiracy: America, Espionage and the Turkish Invasion Archived 31 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b "Turkish invasion of Cyprus". Mlahanas.de. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ "Turkish Army opens fenced-off Famagusta beach exclusively to Turkish nationals & Turkish-Cypriots!". Cyprus Tourism, 30.08.2017. 30 August 2017. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Germany assuages Greek Cypriot fears over Kosovo ruling Archived 27 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine 24 July 2010 Today's Zaman. Retrieved 31 July 2010.

- ^ "Can Kosovo Be A Sample For Cyprus". Cuneyt Yenigun, International Conference on Balkan and North Cyprus Relations: Perspectives in Political, Economic and Strategic Studies Center for Strategic Studies, 2011. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Kosovo's independence is legal, UN court rules". Peter Beaumont, The Guardian (UK), 22.07.2010. 22 July 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ See UN Security Council resolutions endorsing General Assembly resolution 3212(XXIX)(1974).

- ^ UNHCR Archived 27 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine UNHCR country profiles, p. 54

- ^ "Cyprus: referendum on the Annan Plan". Wsws.org. 24 April 2004. Archived from the original on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ a b "Council of Europe Committee on Migration, Refugees and Demography". Archived from the original on 6 February 2006.

- ^ Hoffmeister 2006, p. 57.

- ^ "PRIO Report on 'Settlers' in Northern Cyprus". Prio.no. Archived from the original on 12 February 2009. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Cyprus Mail, 20 May 2015 Archived 25 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine US House asks for report on Cyprus's defence capabilities

- ^ "DDTC Public Portal" (PDF). www.pmddtc.state.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "US Congress ends Cyprus arms embargo, in blow to Turkey". Channel News Asia. 18 December 2019. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "US partially lifts three-decade-old arms embargo on Cyprus". France 24. 2 September 2020. Archived from the original on 7 November 2022. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ "Türkiye slams US decision to lift arms embargo on Greek Cyprus". Hürriyet Daily News. 29 September 2024. Archived from the original on 29 September 2024. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

References

edit- Bolukbasi, Suha (1993). "The Johnson letter revisited". Middle Eastern Studies. 29 (3): 505–525. doi:10.1080/00263209308700963.

- Brinkley, Douglas (1992). Dean Acheson: The Cold War Years, 1953–71. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Erickson, Edward J.; Uyar, Mesut (2020). Phase Line Attila: The Amphibious Campaign for Cyprus, 1974. Marine Corps University Press. doi:10.56686/9781732003088. ISBN 978-1-7320030-8-8.

- Hatziantoniou, Kostas (2007). Κύπρος 1954–1974: Από το Έπος στην Τραγωδία (in Greek). IANOS. ISBN 978-960-426-451-3.

- O'Malley, Brendan; Craig, Ian (1999). The Cyprus Conspiracy. London: IB Tauris. ISBN 978-1-860-64439-9.

- Varnava, Marilena (2020). Cyprus Before 1974: The Prelude to Crisis. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-784-53997-9.

Further reading

editOfficial publications and sources

edit- The House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee report on Cyprus.

- 1st Report of the European Commission of Human Rights; Turkey's invasion in Cyprus and aftermath (20 July 1974 – 18 May 1976)

- 2nd Report of the European Commission of Human Rights; Turkey's invasion in Cyprus and aftermath (19 May 1976 to 10 February 1983)

- European Court of Human Rights Case of Cyprus v. Turkey (Application no. 25781/94)

- Reports by the UN Secretary General regarding developments in Cyprus (22 May 1974 – 6 December 1974)

- UN Security Council documents and resolutions regarding Cyprus (12 August 1974 – 13 December 1974)

- United Nations Peace Keeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP) situation reports (20 July 1974 – 18 August 1974)

- Letters addressed to UN Secretary General regarding Cyprus (13 September 1974 – 31 December 1974)

Books and articles

edit- Adamides, Marios (2018). The Tragic Duel and the Betrayal of Cyprus Coup D'Etat and Turkish Invasion Cyprus 15–24 July 1974. Independently published.

- Barker, Dudley (2005). Grivas, Portrait of a Terrorist. New York, NY: Harcourt: Brace and Company.

- Brewin, Christopher (2000). European Union and Cyprus. Huntingdon: Eothen Press.

- Cranshaw, Nancy (1978). The Cyprus Revolt: An Account of the Struggle for Union with Greece. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Hitchens, Christopher (1984). Cyprus. London: Quartet.

- Hitchens, Christopher (1997). Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger. New York, NY: Verso.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2001). The Trial of Henry Kissinger. New York, NY: Verso.

- Ker-Lindsay, James (2005). EU Accession and UN Peacemaking in Cyprus. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Meyer, James H. (2000). "Policy Watershed: Turkey's Cyprus Policy and the Interventions of 1974" (PDF). WWS Case Study 3/00. Princeton, NJ: Woodrow Wilson School of Public Affairs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- Mirbagheri, Farid (1989). Cyprus and International Peacemaking. London: Hurst.

- Nicolet, Claude (2001). United States Policy Towards Cyprus, 1954–1974: Removing the Greek-Turkish Bone of Contention. Mannheim: Bibliopolis.

- Oberling, Pierre (1982). The Road to Bellapais: The Turkish Cypriot Exodus to Northern Cyprus. Social Science Monographs.

- Panteli, Stavros. The History of Modern Cyprus. Topline Publishing. ISBN 0-948853-32-8.

- Richmond, Oliver (1998). Mediating in Cyprus. London: Frank Cass.

Other sources

edit- ITN documentary, Cyprus, Britain's Grim Legacy

- Channel 4 Television documentary, Secret History – Dead or Alive?

- Europe: Cyprus CIA World Factbook

External links

edit- Media related to Turkish invasion of Cyprus at Wikimedia Commons

- Cyprus-Conflict.net – a neutral educational website on the conflict (archived 17 May 2015)