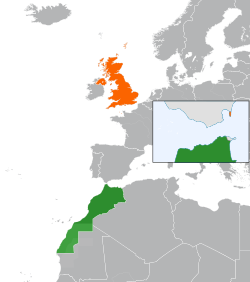

Morocco–United Kingdom relations are the bilateral relations that exist between the Kingdom of Morocco and the United Kingdom.

| |

Morocco |

United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Morocco, London | Embassy of the United Kingdom, Rabat |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Hakim Hajoui | Ambassador Simon Martin |

History

editFirst exchanges

editAccording to some accounts, in the early 13th century, King John of England (1167–1216) sent an embassy to Almohad Sultan Muhammad al-Nasir (1199–1213) to request military support and an alliance against France.[1] At home, King John was faced with a dire situation in which his barons revolted against him, he had been excommunicated by the Pope and France was threatening to invade. The embassy of three was led by Bishop Roger, and King John supposedly offered to convert to Islam and to pay a tribute to al-Nasir in exchange for his help. Al-Nasir apparently dismissed the proposal.[2]

Anglo-Moroccan alliance

editRelations developed following the sailing of The Lion to Morocco in 1551. According to Richard Hakluyt, quoting Edmund Hogan, the ruler "Abdelmelech" (Abu Marwan Abd al-Malik I) bore "a greater affection to our Nation than to others because of our religion, which forbids the worship of Idols".[3]

In 1585, the establishment of the English Barbary Company, trade developed between England and the Barbary states, especially Morocco.[4][5] Diplomatic relations and an alliance were established between Elizabeth and the Barbary states.[6] Queen Elizabeth I sent Roberts to Moroccan Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur to reside in Morocco and to obtain advantages for English traders.[7]

England entered in a trading relationship with Morocco detrimental to Spain by selling armour, ammunition, timber and metal in exchange for Moroccan sugar, in spite of a Papal ban,[8] prompting the Papal Nuncio in Spain to say of Elizabeth I: "there is no evil that is not devised by that woman, who, it is perfectly plain, succoured Mulocco (Abd al-Malik) with arms, and especially with artillery".[9]

1600 embassy

editIn 1600, Abd al-Wahid bin Mas'ud, the principal secretary to Moroccan Sultan Mawlay Ahmad al-Mansur, visited England as an ambassador to the court of Queen Elizabeth I.[4] Abd al-Wahid bin Mas'ud spent six months at the court of Elizabeth to negotiate an alliance against Spain.[11] The Moroccan ruler wanted the help of an English fleet to invade Spain. Elizabeth refused but welcomed the embassy as a sign of insurance and instead accepted to establish commercial agreements.[11][6] Elizabeth and Ahmad continued to discuss various plans for combined military operations, with Elizabeth requesting a payment of 100,000 pounds in advance to king Ahmad for the supply of a fleet and Ahmad asking for a tall ship to be sent to get the money. Discussions, however, remained inconclusive, and both rulers had died within two years of the embassy.[12]

In 1660, Britain took control of Tangier in Morocco following the marriage of Catherine of Braganza to King Charles II in 1661. Along with a large sum of money, the British crown took control of the city, intending to turn it into a major trade gateway into the Mediterranean. Difficulties with administering the city were compounded by religious divisions between the Protestant king in London and the Catholic administrators in Tangier hindered the ability to capitalize on the city's potential as a trade gateway, which culminated in a British withdrawal in 1683.[13]

Later relations

editThe English Garrison of the Colony of Tangier was almost constantly under attack by locals who considered themselves mujahideen fighting a holy war. The Earl of Teviot and around 470 members of the garrison were killed in an ambush beside Jew's Hill.[14] Although the attempt by Sultan Moulay Ismail of Morocco to seize the Tangier had been unsuccessful, a crippling blockade by the Jaysh al-Rifi ultimately forced the English to withdraw.

A treaty signed in 1728 extended the privileges, especially those pertaining to the safe-conduct of English nationals.[15]

Nineteenth century

editThe Sultan banned piracy against European merchants in 1818, and the British perceived this warming of economic relations as a key piece to securing friendly passage into the Mediterranean for strategic and mercantile purposes. In the mid-19th century, Edward Drummond-Hay and his son John Drummond-Hay served as the British consuls-general at Tangier for decades, shaping the country's policies and survival during the Scramble for Africa. Initially, relations near the consulate in Tangier were terse, as various persecutions towards British citizens. Shipwrecked British merchant vessels and their crew were often plundered and enslaved, an entire family of British merchants in Tangier were murdered. The consulate in Tangier, however, was barred on orders from London regarding seeking retribution from the Moroccan sultanate, so as to retain positive foundational relations between the two states. This was due to the desire for British access to Mediterranean markets.[17] The Anglo-Moroccan Accords, also known as the Anglo-Moroccan Treaties of Friendship, were signed on 9 December 1856. This helped prolong Morocco's independence, but reduced its ability to maintain royal trade monopolies within the country and reduced its ability to charge tariffs on foreign commerce. In 1858, British merchants were barred from importing a variety of cash crops from Morocco, such as sugar, tea, and coffee to further enforce the abolition of monopolies.[18] In 1861, Britain issued Morocco a £500,000 loan financed by private investors to help the Sultan pay off the war indemnity of the Hispano-Moroccan War.[19] The last 25 years of the 19th century had multiple exchanges between Britain and Morocco strengthen relations, particularly in terms of exchanging technological advances. In 1877, the first smallpox vaccines arrived in Morocco from Gibraltar. By 1880, the connections between Britain and Morocco warranted the laying of an undersea telegraph cable linking Gibraltar to Tangier.[13]

World War II and pre-independence

editDuring World War II, British intelligence operated heavily in Morocco. Tensions between Britain and Vichy France, along with her colonial holdings, skyrocketed as World War II continued. From 1941-43, British intelligence agents, aided by the United States, planned to subvert the colonial rule of Vichy France by setting up an insurrection with the goal of an independent Morocco. Britain was concerned about the balance of power in the region following Francoist Spain's occupation of Tangier in 1940, and saw a potential entry of Spain on the side of the Axis as a growing concern. However, by 1944, these concerns had faded into the background of British intelligence policy towards Morocco, and British intelligence focused their efforts on remaining within the occupied city of Tangier for information collection.[20] Following World War II, French colonial officials in Morocco were hostile to British involvement in the region, and remained suspicious of potential British activity sponsoring Moroccan independence movements. The incongruity between British and French objectives allowed for Moroccan nationalists to coalesce more efficiently.[21]

British journalism played an important role in pushing for Moroccan independence abroad, particularly in the west. BBC journalist Nina Epton traveled to Morocco in 1946, visiting the notably international city of Tangier. In Tangier, she met with Allal al-Fassi, who told her to "tell people abroad the truth" about Morocco's need for independence. Upon returning to London, Epton wrote in favor of the nationalists multiple times, which helped the independence movement gain traction internationally.[22] Her positive coverage of the nationalist movement included recounting meetings with nationalist leaders, and their alignment to western ideals, in particular the contemporary Atlantic Charter. This coverage was received poorly by colonial officials, however, and Epton was increasingly harassed, even one time being detained and called a highly effective British intelligence agent.[22]

Economic relations

editFrom 26 February 1996 until 30 December 2020, trade between Morocco and the UK was governed by the Morocco–European Union Association Agreement, while the United Kingdom was a member.[24] Following the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union, the UK and Morocco signed a continuity trade agreement on 26 October 2019, based on the EU free trade agreement; the agreement entered into force on 1 January 2021.[25][26] Trade value between Morocco and the United Kingdom was worth £3,288 million in 2022.[27]

Diplomatic relations

editThe Moroccan embassy is located in London.[28]

- Ambassador Hakim Hajoui[29]

The United Kingdom embassy is located in Rabat.[30]

- Ambassador Simon Martin[30]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Britain and Morocco during the embassy of John Drummond Hay, 1845–1886 by Khalid Ben Srhir, Malcolm Williams, Gavin Waterson p.13 [1]

- ^ Najībābādī, Akbar Shāh K̲h̲ān (16 July 2001). History of Islam (Vol 3). Darussalam. ISBN 9789960892931. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Orgel, Stephen; Keilen, Sean (16 July 1999). Shakespeare and History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815329633. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Vaughan, Virginia Mason (12 May 2005). Performing Blackness on English Stages, 1500-1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521845847. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Nicoll, Allardyce (28 November 2002). Shakespeare Survey With Index 1-10. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521523479. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Nicoll, p.90

- ^ Cawston, George; Keane, Augustus Henry (16 July 2001). The Early Chartered Companies (A.D. 1296-1858). The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. ISBN 9781584771968. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bartels, Emily Carroll (16 July 2008). Speaking of the Moor: From Alcazar to Othello. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812240764. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Dimmock, Matthew; Dimmock, Professor of Early Modern Studies Matthew (16 July 2005). New Turkes: Dramatizing Islam and the Ottomans in Early Modern England. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754650225. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ In the lands of the Christians by Nabil Matar, back cover ISBN 0-415-93228-9

- ^ a b Vaughan, p.57

- ^ Nicoll, p.96

- ^ a b Haller, Dieter (2021). Tangier/Gibraltar : a tale of one city : an ethnography. Bielefeld. ISBN 978-3-8394-5649-1. OCLC 1252419648.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lévi-Provençal, Évariste (1936), "Tangier", Encyclopaedia of Islam (1st ed.), Leiden: E.J. Brill, pp. 650–652.

- ^ Cawston, p.226

- ^ "The People of Gibraltar". Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Flournoy, F. R. (March 1932). "Political Relations of Great Britain with Morocco, From 1830 to 1841". Political Science Quarterly. 47 (1): 27–56. doi:10.2307/2142701. JSTOR 2142701.

- ^ "The Levant". The Times of London. 3 October 1853. p. 10.

- ^ Barbe, Adam (August 2016). Public debt and European expansionism in Morocco From 1860 to 1956 (PDF). Paris School of Economics.

- ^ Roslington, James (8 August 2014). "'England is fighting us everywhere': geopolitics and conspiracy thinking in wartime Morocco". The Journal of North African Studies. 19 (4): 501–517. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.945715. ISSN 1362-9387. S2CID 145067317.

- ^ Cline, Walter B. (1947). "Nationalism in Morocco". Middle East Journal. 1 (1): 18–28. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4321825.

- ^ a b Stenner, David (2019). Globalizing Morocco : transnational activism and the post-colonial state. Stanford, California. ISBN 978-1-5036-0900-6. OCLC 1082294927.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ https://www.judaisme-marocain.org/objets_popup.php?id=469

- ^ "EU - Morocco". World Trade Organization. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Burns, Conor (26 October 2019). "UK and Morocco sign continuity agreement". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 27 October 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2024.UK–Morocco FTA

- ^ "UK, Morocco sign continuity agreement". The Arab Weekly. 29 October 2019. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "UK trade agreements in effect". GOV.UK. 3 November 2022. Archived from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

- ^ "Embassy of the Kingdom of Morocco". moroccanembassylondon.org.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Latrech, Oumaima. "Parliamentarian Lauds Diaspora for Promoting Morocco Worldwide". Morocco World News. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ a b "British Embassy Rabat - GOV.UK". www.gov.uk. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

References

edit- Virginia Mason Vaughan Performing Blackness on English Stages, 1500–1800 Cambridge University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-521-84584-X

- Allardyce Nicoll Shakespeare Survey. The Last Plays Cambridge University Press, 2002 ISBN 0-521-52347-8

- George Cawston, Augustus Henry Keane, The Early Chartered Companies (A.D. 1296–1858) The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2001 ISBN 1-58477-196-8

-

Ambassador Admiral Abdallah ben Aisha, 1685.

-

Moroccan Ambassador Mohammed Ben Ali Abgali in 1725.

-

Ambassador Admiral Abdelkader Perez, 1723–1737.

-

Ambassador Zebdi 1876.