This article needs to be updated. (April 2021) |

The United Kingdom national debt is the total quantity of money borrowed by the Government of the United Kingdom at any time through the issue of securities by the British Treasury and other government agencies.

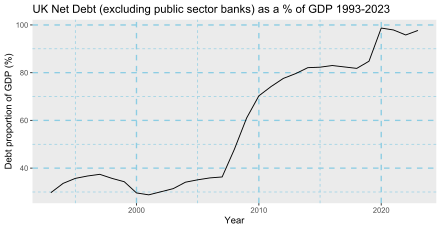

At the end of March 2023, UK general government gross debt was £2,537.0 billion, or 100.5% gross domestic product.[2]

Approximately a third of the UK national debt is owned by the British government due to the Bank of England's quantitative easing programme, so approximately a third of the cost of servicing the debt is paid by the government to itself. In 2018, this reduced the annual servicing cost to approximately £30 billion (approx 2% of GDP, approx 5% of UK government tax income).

In 2017, due to the Government's budget deficit (PSNCR), the national debt increased by £46 billion.[3] The Cameron–Clegg coalition government in 2010 planned that they would eliminate the deficit by the 2015/16 financial year.[4] However, by 2014 they admitted that the structural deficit would not be eliminated until the financial year 2017/18.[5] This forecast was pushed back to 2018/19 in March 2015, and to 2019/20 in July 2015,[6] before the target of a return to surplus at any particular time was finally abandoned by the then Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne in July 2016.[7]

Definition

editThe UK national debt is the total quantity of money borrowed by the Government of the United Kingdom at any time through the issue of securities by the British Treasury and other government agencies.

Debt versus deficit

editThe UK national debt is often confused with the government budget deficit (officially known as the Public Sector Net Cash Requirement (PSNCR)). For example, the then Prime Minister David Cameron was reprimanded in February 2013 by the UK Statistics Authority for creating confusion between the two, by stating in a political broadcast that his administration was "paying down Britain's debts". In fact, his administration had been attempting to reduce the deficit, not the overall debt; which continued to rise even as the deficit was reduced.[9]

UK budget

editThe public debt increases or decreases as a result of the annual budget deficit or surplus. The British government budget deficit or surplus is the cash difference between government receipts and spending. The British government debt is rising due to a gap between revenue and expenditure. Total government revenue in the fiscal year 2015/16 was projected to be £673 billion, whereas total expenditure was estimated at £742 billion. Therefore, the total deficit was £69 billion. This represented a rate of borrowing of a little over £1.3 billion per week.

Gilts

editThe British government finances its debt by issuing gilts, or Government securities. These securities are the simplest form of government bond and make up the largest share of British government debt.[10] A conventional gilt is a bond issued by the British government that pays the holder a fixed cash payment (or coupon) every six months until maturity, at which point the holder receives the final coupon payment and the return of the principal.

Cost of servicing the debt

editDistinct from both the national debt and the PSNCR is the interest that the government must pay to service the existing national debt. In 2012, the annual cost of servicing the public debt amounted to around £43bn, or roughly 3% of GDP.[11]

By international standards, Britain enjoys very low borrowing costs.

Credit rating

editLike other sovereign debt, the British national debt is rated by various ratings agencies. On 23 February 2013, it was reported that Moody's had downgraded UK debt from Aaa to Aa1, the first time since 1978 that the country has not had an AAA credit rating.[12]

This was described as a "humiliating blow" by Shadow Chancellor Ed Balls. George Osborne, the Chancellor, said that it was "a stark reminder of the debt problems facing our country", adding that "we will go on delivering the plan that has cut the deficit by a quarter". France and the United States of America had each lost their AAA credit status in 2012.[12]

The agency Fitch also downgraded its credit rating for British government debt from AAA to AA+ in April 2013.[13]

Further downgrades were made by Fitch and Standard & Poor's in June 2016, following the UK's vote in the referendum of that month to leave the European Union.[14] Standard & Poor's had hitherto maintained the UK's AAA status.

Remedies for indebtedness

editAll the main political parties in Britain agree that the national debt is too high, but disagree on the best policy to deal with it, with Conservative Party politicians advocating a larger role for cuts to public spending. By contrast, the Labour Party tends to advocate fewer cuts and more emphasis on economic stimulus, higher rates of taxation on wealthier individuals and corporations and new taxes for those. Another body of opinion is that the "consensus" regarding the problematic nature of the national debt is incorrect. The view proposed by economists such as Professor Stephanie Kelton of Stony Brook University in New York is that there is often too much emphasis in political discussions on 'balancing the books'.[15]

History

editThe origins of the British national debt can be found during the reign of William III, who engaged a syndicate of City traders and merchants to offer for sale an issue of government debt. This syndicate soon evolved into the Bank of England, eventually financing the wars of the Duke of Marlborough and later imperial conquests. The national debt increased dramatically during and after the Napoleonic Wars, rising to around 200% of GDP. Over the course of the 19th century the national debt gradually fell, only to see large increases again during World War I and World War II. After the war, the national debt once again slowly fell as a proportion of GDP.

Modern era

editIn 1976, the British Government led by James Callaghan faced a Sterling crisis during which the value of the pound tumbled and the government found it difficult to raise sufficient funds to maintain its spending commitments. The Prime Minister was forced to apply to the International Monetary Fund for a £2.3 billion rescue package; the largest-ever call on IMF resources up to that point.[16] In November 1976, the IMF announced its conditions for a loan, including deep cuts in public expenditure, in effect taking control of UK domestic policy.[17] The crisis was seen as a national humiliation, with Callaghan being forced to go "cap in hand" to the IMF.[18]

Recent history

editIn the late 1990s and early 2000s, the national debt dropped in relative terms, falling to 29% of GDP by 2002. In 1997, the Labour Government of Tony Blair had inherited a PSNCR of approximately £5 billion per annum, but by sticking to the spending plans of the outgoing Conservative Government, this was gradually turned into a modest budget surplus.[19] During the Spending Review of 2000, Labour began to pursue a looser fiscal policy, and by 2002 annual borrowing had reached £20 billion.[19]

The national debt continued to increase, together with sustained economic growth, increasing to 37% of GDP in 2007. This was due to extra government borrowing, largely caused by increased spending on health, education, and social security benefits.[11] Between 2008 and 2013, when the British economy slowed sharply and fell into recession, the national debt rose dramatically, mainly caused by increased spending on social security benefits, financial bailouts for banks, and a significant drop in receipts from stamp duty, corporate tax, and income tax.[11]

In the 20-year period from 1986/87 to 2006/07 government spending in the United Kingdom averaged around 40% of GDP. As a result of the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession, government spending increased to a historically high level of 48% of GDP in 2009/10, partly as a result of the cost of a series of bank bailouts.[20] In July 2007, Britain had government debt at 35.5% of GDP.[20] This figure rose to 56.8% of GDP by July 2009.[21]

The national debt today

editDuring the COVID-19 pandemic, national debt reached £2.004 trillion for the first time due to government spending on virus measures, such as the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme ("furlough scheme").[22]

The national debt stood at £1.786 trillion at the calendar year end 2018, or 85.2% of GDP; as published by the Office for National Statistics.[23] However, the OECD claimed the national debt to be 118.3% of GDP as of 5 January 2021[24]

The annual amount that the government must borrow to plug the gap in its finances used to be known as the public sector borrowing requirement, but is now called the Public Sector Net Cash Requirement (PSNCR). The PSNCR figure for the financial year end 2017 was £46 billion,[3] total British GDP in 2017 was £1.959 trillion.[23]

By historic peacetime standards, the national debt is large and growing. There is concern that official calculations of national debt omit many 'off-book' liabilities which mask the true nature of the debt: for example, Nick Silver of the Institute of Economic Affairs estimated the current British liabilities, including state and public pensions, as well as other commitments by the government, to be near £5 trillion, compared with the Government's estimate of £845 billion (as of 17 November 2010)[25] These liabilities can be compared to total net assets (2010 figures) of £7.3 trillion, which equates to approximately a net worth of £120,000 per head of the population.[26] Based on such a method of calculation, UK national debt would be equivalent to, or potentially exceed, historic highs.

The British government's debt is owned by a wide variety of investors, most notably pension funds. These funds are on deposit, mainly in the form of Treasury bonds at the Bank of England. The pension funds, therefore, have an asset which has to be offset by a liability, or a debt, of the government. As of the end of 2016, 27.6% of the national debt was owed to overseas governments and investors.[27]

International comparisons

editIn 2020, Britain's volume of debt was ranked 3rd internationally according to the CIA World Factbook,[28] behind only Greece and Japan

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "PS: Net Debt (excluding public sector banks) as a % of GDP: NSA - Office for National Statistics". www.ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ "UK government debt and deficit: March 2023". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ a b Lewiss1. "Public sector finances, UK - Office for National Statistics". Ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "George Osborne has failed in his deficit reduction ambitions – and the Tories are likely to pay a price at the ballot box". Independent.co.uk. 27 July 2014.

- ^ Mason, Rowena (10 February 2014). "Clegg backs Osborne's timetable for eliminating UK's structural deficit". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ Liam Halligan (11 July 2015). "George Osborne's savvy display lacked tough fiscal action". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- ^ Emily Cadman; Gemma Tetlow (1 July 2016). "George Osborne abandons 2020 UK surplus target". Financial Times. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "UK 2016 Budget" (PDF). Gov.uk. p. 5.

- ^ "Cameron ticked off for confusing debt and deficit - Andy McSmith - Independent McSmith Blogs". 8 February 2013. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2018.

- ^ "UK Debt Management Office". Dmo.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "UK National Debt". Economics Help. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b Hugh Pym (23 February 2013). "UK loses top AAA credit rating for first time since 1978". BBC News. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Fitch downgrades UK credit rating to AA+". BBC News. 19 April 2013. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "Ratings agencies downgrade UK credit rating after Brexit vote". BBC News. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ Kelton, Stephanie (5 October 2017). "How We Think About The Deficit is Mostly Wrong". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- ^ Benedict Brogan (22 October 2009). "The debt crisis of 1976 offers a vision of the blood, sweat and tears facing David Cameron". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Good-bye Great Britain": 1976 IMF Crisis, K Burk, ISBN 0-300-05728-8

- ^ "Britain may need IMF bail-out, warns David Cameron". The Daily Telegraph. 23 January 2009.

- ^ a b "Public Sector Net Cash Requirement". Politics.co.uk. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Britain's public debt since 1974". The Guardian. 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Britain owes £801,000,000,000". The Scotsman. 21 August 2009.

- ^ "Virus spending pushes UK government debt to £2 trillion". BBC News. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ^ a b Smith. "UK government debt and deficit - Office for National Statistics". Ons.gov.uk. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ "United Kingdom - OECD Data".

- ^ Silver, Nick (10 October 2011). "True level of UK government debt exceeds £5 trillion". Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ "UK worth £7.3 trillion". Office for National Statistics. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Quarterly Review January – March 2017". UK Debt Management Office. May 2017. p. 3.

- ^ CIA. "Country Comparisons - Public debt". Archived from the original on 22 February 2024.

References

edit- Ferguson, Niall, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, Penguin Books, London (2008)

- The Week, p. 15, 21 September 2013

External links

edit- BBC Budget 2009 Overview

- Telegraph.co.uk 2011 Budget coverage

- BBC Budget 2008 Overview

- HM Treasury Whole of Government Accounts development programme

- Better Government Initiative experts say billions wasted on services, Daily Telegraph, 24 November 2007

- Better Government Initiative

- UK National Debt Clock

- PricewaterhouseCoopers budget coverage and analysis

- The UK Economy at the Crossroads, research paper from the Center for Economic and Policy Research, March 2018