9°58′N 139°40′E / 9.97°N 139.67°E

Ulithi (Yapese: Wulthiy, Yulthiy, or Wugöy;[1] pronounced roughly as YOU-li-thee[2][needs IPA]) is an atoll in the Caroline Islands of the western Pacific Ocean, about 191 km (103 nmi) east of Yap, within Yap State.

Overview

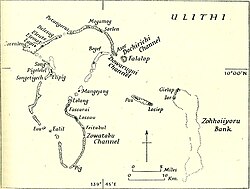

editUlithi consists of 40 islets totaling 4.5 km2 (1+3⁄4 sq mi), surrounding a lagoon about 36 km (22 mi) long and up to 24 km (15 mi) wide—at 548 km2 (212 sq mi) one of the largest in the world. It is administered by the state of Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia. Ulithi's population was 773 in 2000. There are four inhabited islands on Ulithi Atoll. They are Falalop (Ulithian: Fl'aalop), Asor (Yasor), Mogmog (Mwagmwog), and Fedarai (Fedraey). Falalop is the most accessible with Ulithi Airport, a small resort hotel, store and one of three public high schools in Yap state. Mogmog is the seat of the high chief of Ulithi Atoll though each island has its own chief. Other important islands are Losiap (Ulithian: L'oosiyep), Sorlen (Sohl'oay), and Potangeras (Potoangroas).

The atoll is in the westernmost of the Caroline Islands, 580 km (360 mi) southwest of Guam, 1,370 km (850 mi) east of the Philippines and 2,100 km (1,300 mi) south of Tokyo. It is a typical volcanic atoll, with a coral reef, white sand beaches and palm trees. Ulithi's forty small islands barely rise above the sea, with the largest being only 1.3 square kilometers (1⁄2 square mile) in area. However the reef runs roughly thirty kilometers (20 miles) north and south, by fifteen kilometers (10 miles) across, enclosing a vast anchorage with an average depth of 20 to 30 meters (80–100 ft).

History

editThe Portuguese navigator Diogo da Rocha is credited as the first European to find Ulithi in 1525.[3] The Spanish navigator Álvaro de Saavedra arrived on the ship Florida on 1 January 1528, claiming the islands for King Philip II under the name Islands of the Kings (Spanish: Islas de los Reyes; French: Îles des Rois) after his patron and the Three Wise Men honored in the approaching Catholic feast of Epiphany. It was later charted by other Spaniards as the Chickpea Islands (Spanish: Islas de los Garbanzos).[4] It was also visited by the Spanish expedition of Ruy López de Villalobos on 26 January 1543.[5][6]

It remained isolated until visited and explored in detail by Captain Don Bernardo de Egoy in 1712, and later visited by Spanish Jesuit missionaries led by Juan Antonio Cantova together with a group of 12 Spanish soldiers in 1731.[7]

In 1885, Jesuit missionaries encouraged Germany to extend "protection" over the Carolina Islands to protect their profitable trade.[8] However, the Spanish made similar claims and later that year Pope Leo XIII decreed Spain as the ruling power over the islands, granting Germany and the United Kingdom trading rights.[9][10]

In 1889, a significant earthquake hit Yap (and Ulithi),[11] leading the residents to believe that their engagement with outsiders had angered their traditional spirits.[12]

Germany purchased the islands from Spain in 1899 for $4,500,000, conscripting residents as laborers and soldiers.[13] By the early 1900s, Germany had established a police force, post offices and hospitals on Yap,

During this time, German Capuchin friars began to replace the Jesuits. The friars struggled to convert the citizens to Catholicism.[11] According to a history of the Catholic Church in Micronesia:

Yap had been known as "the child of sorrow" of the Caroline mission right from the start. The people were very slow to accept the new faith and slower still to practice it, the missionaries remarked again and again. There were none of the mass conversions there that had occurred in Pohnpei and other parts of the mission. Converts were made laboriously one by one, with baptisms rarely exceeding 20 or 30 a year throughout the German period. Even those who did receive baptism were all too susceptible to the pagan influences of the social environment, the missionaries thought. The number receiving the sacraments was quite small, even for the modest-sized congregations that the priests had. A pastor would report for a typical year perhaps a single Christian marriage, one or two Christian burials and a few anointing.[11]

Good Friday Typhoon

editThe "Good Friday Typhoon" hit the atoll in 1907, which killed 473 throughout the Caroline Islands. SMS Planet was dispatched by the Germans to Ulithi for emergency food and relief, and eventually evacuated 114 residents to Yap. German authorities were caught unaware of how to respond to the disaster, and received much criticism for handling of the evacuation.[14]

Japanese administration

editThe atoll was peacefully occupied in 1914 by Japan at the outset of the First World War. Japan was given a mandate to oversee the territory in 1920 by the League of Nations.[15] Under the Japanese occupation, businessmen and soldiers eroded the traditional political system in Ulithi, with the authority of local chiefs ignored. This began a steady decline in the customs and individual culture of the people of Ulithi.[16] The presence of the Catholic church was reinforced by the Japanese, who allowed the continued efforts of conversion to go on, further eroding the indigenous culture. By 1941, two-thousand (out of 3,000) residents had been converted to Christianity.[11]

World War II

editEarly in the Second World War, the Japanese had established a radio and weather station on Ulithi and had occasionally used the lagoon as an anchorage, but had abandoned it by 1944. As the operations of the United States Navy (USN) moved west across the Pacific, the USN required a more forward base for its operations.

Ulithi was ideally positioned to act as a staging area for the USN's western Pacific operations.[18][19] The anchorage was large and well situated for a base, but there were no port facilities to repair ships or resupply the fleet. The US Navy built the very large Naval Base Ulithi that operated in 1944 and 1945.[20]

On 23 September 1944, a regiment of the United States Army's 81st Division landed unopposed, followed a few days later by a battalion of Seabees.[21] The survey ship USS Sumner examined the lagoon and reported it capable of holding 700 vessels—a capacity greater than either Majuro or Pearl Harbor.

On 1 October 1944, the minesweeper USS YMS-385 was sunk by a mine while clearing Zowariau [Zowatabu] Channel.[22]

The USN transferred the local islanders to the island of Fedarai for the duration of the hostilities. On 4 October 1944 the vessels of Service Squadron 10 began leaving Eniwetok for Ulithi; Service Squadron 10 was termed by Admiral Nimitz as his "secret weapon".[23] Its commanding officer, Commodore Worrall R. Carter, devised the mobile service force that made it possible for the Navy to convert Ulithi to the secret distant Pacific base used during the major naval operations undertaken late in the war, including Leyte Gulf and the invasion of Okinawa. Service Squadron 10 converted the lagoon into a serviceable naval station, creating repair facilities and re-supply facilities thousands of miles away from an actual naval port. Pontoon piers of a new design were built at Ulithi, each consisting of the 4-by-12-pontoon sections, filled with sand and gravel, and then sunk. The pontoons were anchored in place by guy ropes to deadmen on shore, and by iron rods driven into the coral. Connecting tie pieces ran across the tops of the pontoons to hold them together into a pier. Despite extremely heavy weather on several occasions these pontoon piers stood up remarkably well. They gave extensive service, with little requirement for repairs. Piers of this type were also installed by the 51st Battalion to be used as aviation-gasoline mooring piers near the main airfield on Falalop.[20]

Within a month of the occupation of Ulithi, a complete floating base was in operation. Six thousand ship fitters, artificers, welders, carpenters and electricians arrived aboard repair ships, destroyer tenders, and floating dry docks. USS Ajax had an air-conditioned optical shop and a metal fabrication shop with a supply of base metals from which she could make any alloy to form any part needed. USS Abatan, which looked like a big tanker, distilled fresh water and baked bread and pies. The ice cream barge made 1,900 L (500 US gal) a shift.[20] The dry docks towed to Ulithi were large enough to lift dry a 45,000-ton battleship.[23]

Fleet oilers sortied from Ulithi to meet the task forces at sea, refueling the warships a short distance from their combat operational areas. The result was something never seen before: a vast floating service station enabling the entire Pacific fleet to operate indefinitely at unprecedented distances from its mainland bases. Ulithi was as far away from the US naval base at San Francisco as San Francisco was from London, England. The Japanese had considered that the vastness of the Pacific Ocean would make it very difficult for the US to sustain operations in the western Pacific. With the Ulithi naval base to refit, repair and resupply, many ships were able to deploy and operate in the western Pacific for a year or more without returning to the naval base at Pearl Harbor.[24]

The Japanese had built an airstrip on Falalop. It was expanded and resurfaced, the runway running the full width of the island. The east end of the strip was extended approximately six meters (20 feet) past the natural shoreline.[25] During the operations, 4,500 sacks of mail, 262,000 pounds (119,000 kg) of air freight and 1,200 passengers would utilize this airstrip.[26] A number of small strips for light aircraft were built on several of the smaller islands. The Seabees completed a fleet recreation center at Mog Mog island that could accommodate 8,000 men and 1,000 officers daily. A 1,200-seat theatre, including an 8-by-12-meter (25 by 40 ft) stage with a Quonset hut roof was completed in 20 days.[27] At the same time, a 500-seat chapel was built. A number of the larger islands were used both as bases to support naval vessels and facilities within the lagoon.[28]

The Japanese still held Yap. Early after the US occupation they mounted a number of attacks but caused no damage to the Seabees working on the islands.

On 20 November 1944 the Ulithi harbor was attacked by Japanese kaiten manned torpedoes launched from two nearby submarines. The destroyer USS Case rammed one in the early morning hours. At 5:47 the fleet oiler USS Mississinewa, at anchor in the harbor, was struck and sunk. Destroyers began dropping depth charges throughout the anchorage. After the war Japanese naval officers said that two tender submarines, each carrying four manned torpedoes, had been sent to attack the fleet at Ulithi. Three of the kaiten were unable to launch due to mechanical problems and another ran aground on the reef. Two did make it into the lagoon, one of which sank USS Mississinewa. A second kaiten attack in January 1945 was foiled when I-48 was sunk by the destroyer escort USS Conklin. None of the 122 men aboard the Japanese submarine survived.[29]

On 11 March 1945, in a mission known as Operation Tan No. 2, several long range aircraft flying from southern Japan attempted a nighttime kamikaze attack on the naval base.[30] One struck the Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Randolph, which had left a cargo light on despite the black out. The plane struck over the stern starboard quarter, damaging the flight deck and killing a number of crewmen.[31] Another crashed on Sorlen Island, having perhaps mistaken a signal tower there for the superstructure of an aircraft carrier.[32]

By 13 March there were 647 ships at anchor at Ulithi, and with the arrival of amphibious forces staging for the invasion of Okinawa the number of ships at anchor peaked at 722.

In late June 1945, the Japanese aircraft-launching super submarines I-400 and I-401 were diverted from their planned attack on the Panama Canal to attack Ulithi Atoll. However, their mission was interrupted by the destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, followed by the Japanese surrender.

After the Leyte Gulf was secured, the Pacific Fleet moved its forward staging area to Leyte, and Ulithi was all but abandoned. In the end, few US civilians ever heard of Ulithi. By the time naval security cleared release of the name, there were no longer reasons to print stories about it. The war had moved on, but for seven months in late 1944 and early 1945, the large lagoon of the Ulithi atoll was the largest and most active anchorage in the world.[20]

-

USS Randolph undergoing repairs following a kamikaze attack at Ulithi

-

The first mail call in almost three months for Marine Aircraft Group 45., 1944

-

The musical group "Tune Toppers" performs on Ulithi, 1944.

Postwar

editThe LORAN (long-range navigation) station established on Potangeras during the naval occupation on the island continued to be operated by the United States Coast Guard post-war. The station was moved from Potangeras to Falalop Island in 1952. According to an August 1950 "HQ Party Inspection" memo, the move was predicated on the distance between Falalop and Potangeras, requiring a "four hour DUKW [amphibious transport] ride...". The memo goes on to state "...the use of DUKW is dangerous and will eventually lead to disaster. In addition considerable maintenance is required to keep the DUKW in an operating condition".[33]

A 1956 USCG survey indicated that the station consisted of a BOQ and office, galley and meeting area, laundry building, barracks, signal-power building, recreation building and a "jumbo Quonset". All of the buildings, with the exception of the signal-power, were Quonset structures. The report discusses the daily life and routine at the station as follows:

General life on the station is relaxed and fairly routine. Life here can be boring, or very interesting, depending upon how much the individual desires to do. There are practically unlimited recreational facilities, but it is easy to neglect these and fall into a rather lethargic rut. The working hours...are 7AM to 1PM, six days a week. Afternoons and evenings are free...Loran watch standers average about four hours on watch, ten off...their off watch time is their own, and no daywork is expected from them. The uniform to be worn is chosen for coolness and health with shorts and sandals permissible and the rule rather than the exception. Dress blues are not needed here at all.

The Station is completely isolated, and there is no opportunity for liberty or leave. Of course, there is no use for cars here, and dependents are not allowed. All supplies and mail come from Guam...flights averaging one every week or ten days. Every three months heavy supplies and fuel are delivered...and once a year, USCGC Kukui makes a stop here.

The cost of living for personnel here is very cheap, with little opportunity to spend money. Necessary items such as soap, cigarettes, toothpaste are stocked and beer and soda are on sale during non-working hours. Native handicraft is limited to canoe models, small statutes and grass skirts, which seldom run more than five or six dollars. Once a month a shopping list is sent to Guam...men can order anything that can be purchased on Guam...there is always Sears and Roebuck or Montgomery Ward. Officers are charged for three meals a day, regardless whether they eat them or not...about $50.00 a month.

As mentioned before, the recreational facilities are numerous and varied, and include: Swimming...spear fishing...fishing...shelling...photography...leather craft...Ham radio...volleyball..tennis..pool...horse shoes...movies...baseball & softball...boat trips...shooting.

In conclusion...this station has many advantages and few disadvantages, as compared with other Loran Stations. The weather and climate are close to ideal, the station and equipment are in excellent repair, recreational facilities are many and varied, supplies and mail are better than average, and the natives are interesting, sincere honest people. The only disadvantage...is the isolation. All in all, this is a pretty wonderful place.[34]

The station remained in operation until 1965, when they were again relocated to Yap.

A detailed census in 1949 reported that there were 421 inhabitants, mostly elderly. A follow-up census in 1960 showed a rise to 514, with the ratio of men to women having shifted to a small preponderance of males.[35]

Typhoon Ophelia

editTyphoon Ophelia struck the atoll on November 30, 1960, and caused significant damage both physically and socially.

The Coast Guard on the island of Falalop was first notified of a possible tropical disturbance two days prior to the actual typhoon. No action was taken at that time by the personnel other than to observe on a chart of the area the progress of the storm. The next day the station was notified from Guam that it was to take certain safeguarding precautions. While the personnel was engaged in this activity, the winds picked up so noticeably that the local commanding officer notified the Coast Guard section on Guam it was going to move...equipment, personal gear, and emergency rations to a concrete bunker.

Contemporary Ulithi

editAs a major staging area for the United States Navy in the final year of the Second World War, several sunken warships rest at the bottom of the Ulithi lagoon, including USS Mississinewa, a fleet oiler which sank fully loaded.[36][15] In April 2001, sport divers located the wreckage, and four months later oil was observed leaking from the tanks. Several surveys were completed in 2001 and 2002 to determine the status of the wreckage and the leaks. Between January and February 2003, Navy and subcontractors successfully emptied the fuel and oil, with 99% that remained in the wreckage removed.[37]

Occasional diving and adventure tours visit Ulithi from Yap. Given permission from the local community, the atoll offers good diving.[38]

Census records can be misleading because population can fluctuate during the year because it is common for Ulithians to leave for work or school abroad and to return. This is particularly true during festive times like the Outer Island High School graduation ceremony, when the population can increase considerably. Additionally, during events like weddings and funerals, community populations may double.

In 2009, with funding from the European Union (EU) and the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) partnership installed 215 solar photovoltaic (PV) system in Ulithi, with a 28 kWp (kilowatt peak) solar plant. Inverters with a capacity of 20 kW supply 240V / 60 Hz AC into an underground, ostensibly typhoon-proof grid.[39]

Typhoon Maysak

editReef damage from Typhoon Maysak in 2015 is still visible in places, but the reefs have largely recovered. Maysak also caused significant damage to the PV electrical grid system on the atoll.[40]

Conservation

editSince 2018, the Island Conservation[41] group has led an effort with the local community to help stop invasive species from overtaking native green sea turtles and seabirds.[42] One of the non-native species they are attempting to eradicate is the monitor lizard, first introduced during the Japanese occupation to rid the islands of rats.[35]

In 2019, the US Navy submarine tender USS Emory S. Land visited the atoll, as part of the research for US plans for establishing a logistics network across the Pacific, with a Naval press release noting Ulithi "could again represent a logistical hub capable of supporting the fleet".[43]

Transportation

editLocated on Falalop Island, the Ulithi Civil Airfield (IATA code ULI, FAA Identifier TT02) serves as the main air link with the rest of Federated States of Micronesia. With no regularly scheduled flights, service is provided by Pacific Missionary Aviation.[44]

Transport between the smaller closely located islands Ulithi is typically undertaken by motorboat. The ship Halipmohol operates as a Field Trip Ship, transiting on a semi-regular basis throughout the Yap outer islands.[45] According to the Pacific Worlds website, it is customary to request permission from the Chief of Ulithi to visit the atoll.[46]

Culture

editTraditionally, Ulithi culture was based on matriarchal lineages. Each lineage had a male chief by seniority. Each village had a village council to help with everyday issues, as well as questions concerning the entire atoll. Land was owned by the lineages and parceled out for different uses. Women typically handle the agricultural duties, while men fished. Religion was pagan-based, spirits and ancestral ghosts. Magic was also incorporated into the everyday life, prevalent in disease/medicine, navigation, weather and fishing. Sociological studies showed that by 1960, after decades of influence by outsiders, the traditional religion had all but vanished, to be replaced by Christianity.[35]

Language

editIn an annual report released in early 2010, the Habele charity announced plans to develop and distribute native-language materials for educators and students in the outer islands of Yap State, Micronesia. The first project was a Ulithian-to-English dictionary.[47] This was the first rigorous documentation of the Ulithian language, and copies were provided to educators and students throughout Ulithi and Fais.[48] The authors' stated aim was to create a consistent and intuitive Latin alphabet useful for both native Ulithian and native English speakers.

Education

editPublic schools:[49]

Climate

editUlithi has a tropical rainforest climate (Af) with heavy rainfall year-round.

| Climate data for Ulithi | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.6 (87.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.7 (87.3) |

31.2 (88.1) |

31.3 (88.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.1 (87.9) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.3 (88.4) |

30.8 (87.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.4 (81.4) |

27.3 (81.2) |

27.6 (81.6) |

27.9 (82.3) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.7 (81.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.3 (81.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.7 (81.8) |

27.6 (81.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

24.1 (75.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.9 (76.9) |

24.3 (75.8) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.9 (75.1) |

23.9 (75.1) |

24.2 (75.5) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.6 (76.2) |

24.3 (75.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 153.2 (6.030) |

113.3 (4.460) |

134.4 (5.290) |

127.0 (5.000) |

167.6 (6.600) |

257.6 (10.140) |

306.8 (12.080) |

393.7 (15.500) |

320.0 (12.600) |

251.2 (9.890) |

228.6 (9.000) |

196.1 (7.720) |

2,649.5 (104.31) |

| Source: [50] | |||||||||||||

References

edit- ^ "Ulithi". Yapese Dictionary: English Finderlist. Updated 27 July 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ William A. Lessa, Ulithi: A Micronesian Design for Living (Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966).

- ^ Quanchi, Max (2005). Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands. The Scarecrow Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 0810853957.

- ^ Langdon, Robert (1975). The Lost Caravel. Sidney: Pacific Publications. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-85807-021-9.

- ^ Sharp, Andrew The discovery of the Pacific Islands Oxford, 1960, p.32.

- ^ Brand, Donald D. (1967). The Pacific Basin: A History of its Geographical Explorations. New York: The American Geographical Society. p. 123.

- ^ Burney, James (1817). A Chronological History of the Discoveries of the South Sea or Pacific Ocean: To the year 1764. London: Luke Hansard & Sons. ISBN 978-1-108-02411-2.

- ^ Reclus, Elisée (1890). The Earth and Its Inhabitants, Oceanica. D. Appleton.

- ^ Quinn, Pearle E. (1945). "The Diplomatic Struggle for the Carolines, 1898". Pacific Historical Review. 14 (3): 290–302. doi:10.2307/3635892. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3635892.

- ^ Lorente, Marta (2018-12-11). "Historical Titles v. Effective Occupation: Spanish Jurists on the Caroline Islands Affair (1885)". Journal of the History of International Law / Revue d'histoire du droit international. 20 (3): 303–344. doi:10.1163/15718050-12340089. ISSN 1388-199X. S2CID 231020261.

- ^ a b c d "Catholic Church in Micronesia: Yap". micronesianseminar.org. Archived from the original on 2022-01-07. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ "Yap: Ulithi -- Memories: Chronology". www.pacificworlds.com. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

- ^ Sueo, Kuwahara (2003). "TRADITIONAL CULTURE, TOURISM, AND SOCIAL CHANGE IN MOGMOG ISLAND, ULITHI ATOLL" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ Spennemann, Dirk R. (2007). Melimel : the Good Friday typhoon of 1907 and its aftermath in the Mortlocks, Caroline Islands. Albury, N.S.W.: retro spect. ISBN 978-1-921220-07-4. OCLC 192106802.

- ^ a b Fulleman, Bob (November 2009). "AO-59 USS Mississinewa". Archived from the original on 2018-06-15. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ^ Figirliyong, Josede. “The contemporary political system of Ulithi Atoll.” (1976).

- ^ "Finlayson Files". Finlayson Files. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ Jones, Brent (December 2007). "Chapter 8: Reporting For Duty". Mighty Ninety, The Homepage of USS Astoria CL-90.

- ^ "Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineering Corps, 1940-1946, Volume II". Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. 1947. p. 332. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d Spangler, George (March 1998). "Ulithi". USS Laffey.

- ^ Antill, Peter (28 February 2003). "Battle for Anguar and Ulithi (Operation Stalemate II) September 1944". Military History Encyclopedia on the Web.

- ^ "USS YMS-385". uboat.net. Retrieved 2022-08-12.)

- ^ a b "ServRon 10: Floating Arsenal". Popular Mechanics: 59. November 1945. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "World Battlefronts: Mighty Atoll". Time. August 6, 1945. Archived from the original on December 21, 2011.

- ^ "Building the Navy's Bases in World War II: History of the Bureau of Yards and Docks and the Civil Engineering Corps, 1940-1946, Volume II". Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. 1947. p. 334. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Ulithi Top Secret". usselmore.com. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Slagg, John. "Where is Mog Mog?".

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). History of United States Naval Operations in World War II: Leyte. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 47–50. ISBN 0-252-07063-1.

- ^ "Japanese submarine losses". Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- ^ Arnold, Bruce Makoto (August 2007). An Atoll on the Edge of Hell: The U.S. Military's use of Ulithi During World War II (M.A. Thesis). Sam Houston State University. OCLC 173485609.

- ^ Potter, E. B. (2005). Admiral Arliegh Burke. U.S. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-692-6.p. 241

- ^ Bob Hackett (2007). "Operation Tan No. 2: The Japanese Attack on Task Force 58's Anchorage at Ulithi".

- ^ "HEADQUARTERS' PARTY INSPECTION - AUGUST 1950" (PDF). 1950-01-08. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Anthony, C.H. (1956-05-22). "Overseas Loran Station Survey" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ a b c Lessa, William (1964-01-06). "The Social Effects of Typhoon Ophelia (1960) on Ulithi" (PDF). Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Mississinewa (AO-59) I". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "U.S. NAVY SALVAGE REPORT USS MISSISSINEWA OIL REMOVAL OPERATIONS" (PDF). 2004-05-01. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Scuba Diving on the USS Mississinewa (AO-59) Ulithi Atoll- Micronesia - Review of Ulithi Adventure Lodge, Falalop, Federated States of Micronesia - Tripadvisor". www.tripadvisor.com. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "FSM's Largest Solar PV Power Plant Operational in Yap". www.fsmgov.org. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Micro-grid Renewable Energy Systems Damage Assessment Report | PCREEE". www.pcreee.org. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Island Conservation

- ^ "Ulithi Atoll". Island Conservation. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ Woody, Christopher. "The US Navy's recent visit to a vital WWII hub is another sign it's thinking about how to fight in the Pacific". Business Insider. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) Division of Civil Aviation | Ulithi Civil Airfield (TT02) (ULI), Ulithi Atoll, Micronesia". tci.gov.fm. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Photo of the Week: Visiting the Yap Outer Islands". GoMad Nomad. 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ "Yap: Ulithi -- Getting Here". www.pacificworlds.com. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ "Former Micronesia Peace Corps Group Funds Scholarships" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine. Pacific Island Report, East-West Center, January 28, 2010.

- ^ "Charity Publishes Dictionary For Remote Micronesian Islanders" COM-FSM, May 10, 2010.

- ^ "Higher Education in the Federated States of Micronesia Archived 2017-10-14 at the Wayback Machine." Embassy of the Federated States of Micronesia Washington DC. Retrieved on February 23, 2018.

- ^ WRCC

External links

edit- "Its existence kept secret throughout the war, the US naval base at Ulithi was for a time the world's largest naval facility", George Spangler, March 1998

- Ulithi in World War II

- "OPERATION TAN NO. 2: The Japanese Attack on Task Force 58's Anchorage at Ulithi" by Bob Hackett and Sander Kingsepp (Revision 2) at the Imperial Japanese Navy Page

- Habele Outer Island Education Fund, an educational charity serving Ulithi

- An extensive history (Archived 2022-01-07 at the Wayback Machine) of the Catholic Church in Yap and Ulithi