The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the northern province of Ulster. Many Ulster Protestants and Irish unionists feared being governed by a nationalist Catholic-majority parliament in Dublin and losing their links with Great Britain. In 1913, the militias were organised into the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and vowed to resist any attempts by the British Government to impose Home Rule on Ulster. Later that year, Irish nationalists formed a rival militia, the Irish Volunteers, to safeguard Home Rule. In April 1914, the UVF smuggled 25,000 rifles into Ulster from Imperial Germany. The Home Rule Crisis was interrupted by the First World War. Much of the UVF enlisted with the British Army's 36th (Ulster) Division and went to fight on the Western Front.

| Ulster Volunteer Force | |

|---|---|

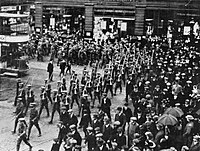

Ulster Volunteers in Belfast, 1914 | |

| Leaders | Edward Carson James Craig |

| Dates of operation | 13 January 1913 – 1 May 1919 (various units active since 1912) 25 June 1920 – early 1922 |

| Headquarters | Belfast |

| Active regions | Ulster |

| Ideology | Ulster loyalism British unionism Opposition to Home Rule |

| Size | Exact size unknown, at least 100,000 in 1912 |

| Part of | Military wing of the Ulster Unionist Council |

| Opponents | Irish nationalists (including Irish republicans) British government |

After the war, the British Government decided to partition Ireland into two self-governing regions: Northern Ireland (which overall had a Protestant/unionist majority) and Southern Ireland. However, by 1920 the Irish War of Independence was raging and the Irish Republican Army (IRA) was launching attacks on British forces in Ireland. In response, the UVF was revived. It was involved in some sectarian clashes and minor actions against the IRA. However, this revival was largely unsuccessful and the UVF was absorbed into the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), the new reserve police force of Northern Ireland.

A loyalist paramilitary group calling itself the Ulster Volunteer Force was formed in 1966. It claims to be a direct descendant of the older organisation and uses the same logo, but there are no organisational links between the two.[1]

Before World War I

editBy 1912, the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP), an Irish nationalist party which sought devolution (Home Rule) for Ireland, held the balance of power in the Parliament of the United Kingdom. In April 1912, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith introduced the third Home Rule Bill. Previous Home Rule Bills had fallen, the first rejected by the House of Commons, the second because of the veto power of the Tory-dominated House of Lords, however since the crisis caused by the Lords' rejection of the "People's Budget" of 1909 and the subsequent passing of the Parliament Act, the House of Lords had seen their powers to block legislation diminished and so it could be expected that this Bill would (eventually) become law. Home Rule was popular in all of Ireland apart from the northeast of Ulster. While Catholics were the majority in most of Ireland, Protestants were the majority in the six counties that became Northern Ireland as well as in Great Britain. Many Ulster Protestants feared being governed by a Catholic-dominated parliament in Dublin and losing their local supremacy and strong links with Britain.[2]

The two key figures in the creation of the Ulster Volunteers were Edward Carson (leader of the Irish Unionist Alliance) and James Craig, supported sub rosa by figures such as Henry Wilson, Director of Military Operations at the British War Office. At the start of 1912, leading unionists and members of the Orange Order (a Protestant fraternity) began forming small local militias and drilling. On 9 April Carson and Bonar Law, leader of the Conservative & Unionist Party, reviewed 100,000 Ulster Volunteers marching in columns.[3] On 28 September, 218,206[4] men signed the Ulster Covenant, vowing to use "all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland", with the support of 234,046 women.[5]

In January 1913, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was formally established by the Ulster Unionist Council.[6] Recruitment was to be limited to 100,000 men aged from 17 to 65 who had signed the Covenant, under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir George Richardson KCB.[7] William Gibson was the first commander of the 3rd East Belfast Regiment of the Ulster Volunteers.[8]

The Ulster Unionists enjoyed the wholehearted support of the British Conservative Party, even when threatening rebellion against the British government. On 23 September 1913, the 500 delegates of the Ulster Unionist Council met to discuss the practicalities of setting up a provisional government for Ulster, should Home Rule be implemented.[9]

On 25 November 1913, partly in response to the formation of the UVF, Irish nationalists formed the Irish Volunteers – a militia whose role was to safeguard Home Rule.[10]

In March 1914, the British Army's Commander-in-Chief in Ireland was ordered to move troops into Ulster to protect arms depots from the UVF. However, 57 of the 70 officers at the Army's headquarters in Ireland chose to resign rather than enforce Home Rule or take on the UVF. The following month, the UVF smuggled 20,000 German rifles with 3,000,000 rounds of ammunition into the port of Larne. This became known as the Larne gunrunning.

The Ulster Volunteers were a continuation of what has been described as the "Protestant volunteering tradition, in Ireland", which since 1666 spans the various Irish Protestant militias founded to defend Ireland from foreign threat.[11] References to the most prominent of these militias, the Irish Volunteers, was frequently made, and there were also attempts to link the activities of the two.[11]

World War I

editThe third Home Rule Bill was eventually passed despite the objections of the House of Lords, whose power of veto had been abolished under the Parliament Act 1911.[12] While Carson had hoped to have the whole of Ulster excluded, he felt a good case could be made for the six Ulster counties with unionist, or only slight nationalist, majorities.[13] However, in August 1914 the Home Rule issue was temporarily suspended by the outbreak of World War I and Ireland's involvement in it. Many UVF men enlisted in the British Army, mostly with the 36th (Ulster) Division[14] of the 'New Army'. Others joined Irish regiments of the United Kingdom's 10th and 16th (Irish) Divisions. By the summer of 1916, only the Ulster and 16th divisions remained, the 10th amalgamated into both following severe losses in the Battle of Gallipoli. Both of the remaining divisions suffered heavy casualties in July 1916 during the Battle of the Somme and were largely wiped out in 1918 during the German spring offensive.[15]

Although many UVF officers left to join the British Army during the war, the unionist leadership wanted to preserve the UVF as a viable force, aware that the issue of Home Rule and partition would be revisited when the war ended. There were also fears of a German naval raid on Ulster and so much of the UVF was recast as a home defence force.[16]

World War I ended in November 1918. On 1 May 1919, the UVF was 'demobilised' when Richardson stood down as its General Officer Commanding. In Richardson's last orders to the UVF, he stated:

Existing conditions call for the demobilisation of the Ulster Volunteers. The Force was organised, to protect the interests of the Province of Ulster, at a time when trouble threatened. The success of the organisation speaks for itself, as a page of history, in the records of Ulster that will never fade.[17]

During Partition

editIn the December 1918 general election, Sinn Féin—an Irish republican party who sought full independence for Ireland—won an overwhelming majority of the seats in Ireland. Its members refused to take their seats in the British Parliament and instead set up their own parliament and declared independence for Ireland. The Irish Volunteers was ostensibly reconstituted as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the military of the self-declared Republic. The Irish War of Independence began, fought between the IRA and the forces of the Crown in Ireland (consisting of various forces including the British Army, the Auxiliaries, and the RIC). The Government of Ireland Act 1920 provided for two Home Rule parliaments: one for Northern Ireland and one for Southern Ireland. The unionist-dominated Parliament of Northern Ireland chose to remain a part of the United Kingdom.

As a response to IRA attacks within Ulster, the Ulster Unionist Council officially revived the UVF on 25 June 1920.[18] Many Unionists felt that the RIC, being mostly Roman Catholic (though this was not the case with regards to Ulster) as a whole, would not adequately protect Protestant areas. In early July, the UUC appointed Lieutenant Colonel Wilfrid Spender as the UVF's Officer Commanding.[18] At the same time, announcements were printed in unionist newspapers calling on all former UVF members to report for duty.[18] However, this call met with limited success; for example, each Belfast battalion drew little more than 100 men each and they were left mostly unarmed.[18] The UVF's revival also met with little backing from unionists in Great Britain.[18]

During the conflict, loyalists set up small independent "vigilance groups" in many parts of Ulster. Most of these groups would patrol their areas and report anything untoward to the RIC. Some of them were armed with UVF rifles from 1914.[19] There were also a number of small loyalist paramilitary groups, the most notable of which was the Ulster Imperial Guards, who may have overreached the UVF in terms of membership.[19] Historian Peter Hart wrote the following of these groups:

Also occasionally targeted [by the IRA] were Ulster Protestants who saw the republican guerrilla campaign as an invasion of their territory, where they formed the majority. Loyalist activists responded by forming vigilante groups, which soon acquired official status as part of the Ulster Special Constabulary. These men spearheaded the wave of anti-Catholic violence that began in July 1920 and continued for two years. This onslaught was part of an Ulster Unionist counter-revolution, whose gunmen operated almost exclusively as ethnic cleansers and avengers.[20]

The UVF was involved in sectarian clashes in Derry in June 1920. Catholic homes were burned in the mainly-Protestant Waterside area, and UVF members fired on Catholics fleeing by boat across the River Foyle. UVF members fired from the Fountain neighbourhood into adjoining Catholic districts, and the IRA returned fire.[21] Thirteen Catholics and five Protestants were killed in a week of violence.[22] In August 1920, the UVF helped organise the mass burning of Catholic property in Lisburn. This was in response to the IRA assassinating an RIC Inspector in the town.[23] By the end of August 1920 an estimate of the material damage done in Belfast, Lisburn and Banbridge was one million pounds.[24] That October, armed UVF members drove off an IRA unit that had attacked the RIC barracks in Tempo, County Fermanagh.[25]

The sluggish recruitment to the UVF and its failure to stop IRA activities in Ulster prompted Sir James Craig to call for the formation of a new special constabulary.[26] In October 1920, the Ulster Special Constabulary (USC) formed, intended to serve as an armed reserve force to bolster the RIC and fight the IRA. Spender encouraged UVF members to join it and many did, although the USC did not engulf the bulk of the UVF (and other loyalist paramilitary groups) until early 1922.[26] Craig hoped to "neutralise" the loyalist paramilitaries by enrolling them in the C Division of the USC, a move that was backed by the British government.[27] Historian Michael Hopkinson wrote that the USC, "amounted to an officially approved UVF".[28] Unlike the RIC, the USC was almost wholly Protestant and was greatly mistrusted by Catholics and nationalists. Following IRA attacks, the USC often carried out revenge killings and reprisals against Catholic civilians.[29]

In his book Carson's Army: the Ulster Volunteer Force 1910–22, Timothy Bowman gave the following as his last thought on the UVF during this period:

It is questionable the extent to which the UVF did actually reform in 1920. Possibly the UVF proper amounted to little more than 3,000 men in this period and it is noticeable that the UVF never had a formal disbandment ... possibly so that attention would not be drawn to the extent to which the formation of 1920–22 was such a pale shadow of that of 1913–14.[30]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ MacDermott, John (1979). An Enriching Life. Privately published. p. 42.

- ^ Bardon, Jonathan (1992). A History of Ulster. Blackstaff Press. pp. 402, 405. ISBN 0856404985.

- ^ "BBC Short History of Ireland: Home Rule promised". Archived from the original on 18 May 2010.

- ^ Holmes, Janice; Urquhart, Diane (1994). Coming into the Light: The Work, Politics and Religion of Women in Ulster 1840-1940. Queen's University Belfast, 1994. ISBN 0-85389539-2.

- ^ "HISTORY OF GREAT BRITAIN (from 1707)". www.historyworld.net. Archived from the original on 11 April 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- ^ "Ireland - The 20th-century crisis". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ Martin, Francis X. (1967). Leaders and Men of the Easter Rising: Dublin 1916. Taylor & Francis. p. 72. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Timothy Bowman, Carson's Army: the Ulster Volunteer Force, 1910-22, p.98

- ^ HM Hyde; Carson. p340-341.

- ^ White, Gerry and O’Shea, Brendan: Irish Volunteer Soldiers 1913-23, p.8, lines 17-21, Osprey Publishing Oxford (2003), ISBN 978-1-84176-685-0

- ^ a b Timothy Bowman (May 2012). Carson's Army, The Ulster Volunteer Force. 1910-22. Manchester University Press. pp. 16, 68. ISBN 9780719073724.

- ^ Macardle, Dorothy (1968). The Irish Republic. Corgi Books. p. 69.

- ^ Kee, Robert (1972). The Green Flag. Penguin Books. p. 478. ISBN 0-14-029165-2.

- ^ Fisk says 35,000 enlisted. 5,000 being killed during the attack on German lines at Thiepval on the Somme. P.15.

- ^ Stewart, A.T.Q. (1967). The Ulster Crisis. Faber & Faber. pp. 237–242.

- ^ Bowman, p.166

- ^ Bowman, pp.182-183

- ^ a b c d e Bowman, Timothy. Carson's Army: the Ulster Volunteer Force 1910–22. p.192

- ^ a b Bowman, p.190

- ^ Peter Hart in, Joost Augusteijn (ed), The Irish Revolution, p.25

- ^ Lawlor, Pearse. The Outrages: The IRA and the Ulster Special Constabulary in the Border Campaign. Mercier Press, 2011. pp. 16–17

- ^ Eunan O'Halpin & Daithí Ó Corráin. The Dead of the Irish Revolution. Yale University Press, 2020. pp.143–145

- ^ Lawlor, pp.115–121, 153

- ^ Macardle, Dorothy (1965). The Irish Republic. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 386.

- ^ Lawlor, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b Bowman, p.195

- ^ Bowman, p.198

- ^ Hopkinson, Irish War of Independence, p. 158

- ^ Michael Hopkinson, The Irish War of Independence, p263

- ^ Bowman, p.201

Bibliography

edit- Proclamation by the UVF in the Larne Times newspaper, January 1914 here.

- Hart, Peter (1998). The IRA and its Enemies: Violence in the Community of Cork, 1912-1923. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198208065.

- Hopkinson, M, Green Against Green – The Irish Civil War: A History of the Irish Civil War

- Hopkinson, M, Irish Revolution

- Montgomery Hyde, H. Carson. Constable, London 1974. ISBN 0-09-459510-0.

- Details on UVF links to the 36th Ulster Division which fought at the Somme here.

- Fisk, Robert In time of War: Ireland, Ulster, and the price of neutrality 1939 - 1945 (Gill & Macmillan) 1983 ISBN 0-7171-2411-8.