This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The ultimatum game is a game that has become a popular instrument of economic experiments. An early description is by Nobel laureate John Harsanyi in 1961.[1] One player, the proposer, is endowed with a sum of money. The proposer is tasked with splitting it with another player, the responder (who knows what the total sum is). Once the proposer communicates their decision, the responder may accept it or reject it. If the responder accepts, the money is split per the proposal; if the responder rejects, both players receive nothing. Both players know in advance the consequences of the responder accepting or rejecting the offer.

Equilibrium analysis

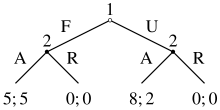

editFor ease of exposition, the simple example illustrated above can be considered, where the proposer has two options: a fair split, or an unfair split. The argument given in this section can be extended to the more general case where the proposer can choose from many different splits.

A Nash equilibrium is a set of strategies (one for the proposer and one for the responder in this case), where no individual party can improve their reward by changing strategy. If the proposer always makes an unfair offer, the responder will do best by always accepting the offer, and the proposer will maximize their reward. Although it always benefits the responder to accept even unfair offers, the responder can adopt a strategy that rejects unfair splits often enough to induce the proposer to always make a fair offer. Any change in strategy by the proposer will lower their reward. Any change in strategy by the responder will result in the same reward or less. Thus, there are two sets of Nash equilibria for this game:

- The proposer always makes an unfair offer, and the responder always accepts an unfair offer. (The proposer never gives a fair offer so the responder can accept fair offers with any frequency without affecting the average reward.)

- The proposer always makes a fair offer. The responder rejects unfair offers often enough to make fair offers at least as profitable as unfair offers, and always accepts fair offers.

However, only the first set of Nash equilibria satisfies a more restrictive equilibrium concept, subgame perfection. The game can be viewed as having two subgames: the subgame where the proposer makes a fair offer, and the subgame where the proposer makes an unfair offer. A perfect-subgame equilibrium occurs when there are Nash Equilibria in every subgame, that players have no incentive to deviate from.[2] In both subgames, it benefits the responder to accept the offer. So, the second set of Nash equilibria above is not subgame perfect: the responder can choose a better strategy for one of the subgames.

Multi-valued or continuous strategies

editThe simplest version of the ultimatum game has two possible strategies for the proposer, Fair and Unfair. A more realistic version would allow for many possible offers. For example, the item being shared might be a dollar bill, worth 100 cents, in which case the proposer's strategy set would be all integers between 0 and 100, inclusive for their choice of offer, S. This would have two subgame perfect equilibria: (Proposer: S=0, Accepter: Accept), which is a weak equilibrium because the acceptor would be indifferent between their two possible strategies; and the strong (Proposer: S=1, Accepter: Accept if S>=1 and Reject if S=0).[3]

The ultimatum game is also often modelled using a continuous strategy set. Suppose the proposer chooses a share S of a pie to offer the receiver, where S can be any real number between 0 and 1, inclusive. If the receiver accepts the offer, the proposer's payoff is (1-S) and the receiver's is S. If the receiver rejects the offer, both players get zero. The unique subgame perfect equilibrium is (S=0, Accept). It is weak because the receiver's payoff is 0 whether they accept or reject. No share with S > 0 is subgame perfect, because the proposer would deviate to S' = S - for some small number and the receiver's best response would still be to accept. The weak equilibrium is an artifact of the strategy space being continuous.

Experimental results

editThe first experimental analysis of the ultimatum game was by Werner Güth, Rolf Schmittberger, and Bernd Schwarze:[4] Their experiments were widely imitated in a variety of settings. When carried out between members of a shared social group (e.g., a village, a tribe, a nation, humanity)[5] people offer "fair" (i.e., 50:50) splits, and offers of less than 30% are often rejected.[6][7]

One limited study of monozygotic and dizygotic twins claims that genetic variation can have an effect on reactions to unfair offers, though the study failed to employ actual controls for environmental differences.[8] It has also been found that delaying the responder's decision leads to people accepting "unfair" offers more often.[9][10][11] Common chimpanzees behaved similarly to humans by proposing fair offers in one version of the ultimatum game involving direct interaction between the chimpanzees.[12] However, another study also published in November 2012 showed that both kinds of chimpanzees (common chimpanzees and bonobos) did not reject unfair offers, using a mechanical apparatus.[13]

Cross-cultural differences

editSome studies have found significant differences between cultures in the offers most likely to be accepted and most likely to maximize the proposer's income. In one study of 15 small-scale societies, proposers in gift-giving cultures were more likely to make high offers and responders were more likely to reject high offers despite anonymity, while low offers were expected and accepted in other societies, which the authors suggested were related to the ways that giving and receiving were connected to social status in each group.[14] Proposers and responders from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) societies are most likely to settle on equal splits.[15][16][17]

Framing effects

editSome studies have found significant effects of framing on game outcomes. Outcomes have been found to change based on characterizing the proposer's role as giving versus splitting versus taking,[18] or characterizing the game as a windfall game versus a routine transaction game.[19]

Explanations

editThe highly mixed results, along with similar results in the dictator game, have been taken as both evidence for and against the Homo economicus assumptions of rational, utility-maximizing, individual decisions. Since an individual who rejects a positive offer is choosing to get nothing rather than something, that individual must not be acting solely to maximize their economic gain, unless one incorporates economic applications of social, psychological, and methodological factors (such as the observer effect).[citation needed] Several attempts have been made to explain this behavior. Some suggest that individuals are maximizing their expected utility, but money does not translate directly into expected utility.[20][21] Perhaps individuals get some psychological benefit from engaging in punishment or receive some psychological harm from accepting a low offer.[citation needed] It could also be the case that the second player, by having the power to reject the offer, uses such power as leverage against the first player, thus motivating them to be fair.[22]

The classical explanation of the ultimatum game as a well-formed experiment approximating general behaviour often leads to a conclusion that the rational behavior in assumption is accurate to a degree, but must encompass additional vectors of decision making.[23] Behavioral economic and psychological accounts suggest that second players who reject offers less than 50% of the amount at stake do so for one of two reasons. An altruistic punishment account suggests that rejections occur out of altruism: people reject unfair offers to teach the first player a lesson and thereby reduce the likelihood that the player will make an unfair offer in the future. Thus, rejections are made to benefit the second player in the future, or other people in the future. By contrast, a self-control account suggests that rejections constitute a failure to inhibit a desire to punish the first player for making an unfair offer. Morewedge, Krishnamurti, and Ariely (2014) found that intoxicated participants were more likely to reject unfair offers than sober participants.[24] As intoxication tends to exacerbate decision makers' prepotent response, this result provides support for the self-control account, rather than the altruistic punishment account. Other research from social cognitive neuroscience supports this finding.[25]

However, several competing models suggest ways to bring the cultural preferences of the players within the optimized utility function of the players in such a way as to preserve the utility maximizing agent as a feature of microeconomics. For example, researchers have found that Mongolian proposers tend to offer even splits despite knowing that very unequal splits are almost always accepted.[26] Similar results from other small-scale societies players have led some researchers to conclude that "reputation" is seen as more important than any economic reward.[27][26] Others have proposed the social status of the responder may be part of the payoff.[28][29] Another way of integrating the conclusion with utility maximization is some form of inequity aversion model (preference for fairness). Even in anonymous one-shot settings, the economic-theory suggested outcome of minimum money transfer and acceptance is rejected by over 80% of the players.[30]

An explanation which was originally quite popular was the "learning" model, in which it was hypothesized that proposers' offers would decay towards the sub game perfect Nash equilibrium (almost zero) as they mastered the strategy of the game; this decay tends to be seen in other iterated games.[citation needed] However, this explanation (bounded rationality) is less commonly offered now, in light of subsequent empirical evidence.[31]

It has been hypothesized (e.g. by James Surowiecki) that very unequal allocations are rejected only because the absolute amount of the offer is low.[32] The concept here is that if the amount to be split were 10 million dollars, a 9:1 split would probably be accepted rather than rejecting a 1 million-dollar offer. Essentially, this explanation says that the absolute amount of the endowment is not significant enough to produce strategically optimal behaviour. However, many experiments have been performed where the amount offered was substantial: studies by Cameron and Hoffman et al. have found that higher stakes cause offers to approach closer to an even split, even in a US$100 game played in Indonesia, where average per-capita income is much lower than in the United States. Rejections are reportedly independent of the stakes at this level, with US$30 offers being turned down in Indonesia, as in the United States, even though this equates to two weeks' wages in Indonesia. However, 2011 research with stakes of up to 40 weeks' wages in India showed that "as stakes increase, rejection rates approach zero".[33] It is worth noting that the instructions offered to proposers in this study explicitly state, "if the responder's goal is to earn as much money as possible from the experiment, they should accept any offer that gives them positive earnings, no matter how low," thus framing the game in purely monetary terms.

Neurological explanations

editGenerous offers in the ultimatum game (offers exceeding the minimum acceptable offer) are commonly made. Zak, Stanton & Ahmadi (2007) showed that two factors can explain generous offers: empathy and perspective taking.[34][35] They varied empathy by infusing participants with intranasal oxytocin or placebo (blinded). They affected perspective-taking by asking participants to make choices as both player 1 and player 2 in the ultimatum game, with later random assignment to one of these. Oxytocin increased generous offers by 80% relative to placebo. Oxytocin did not affect the minimum acceptance threshold or offers in the dictator game (meant to measure altruism). This indicates that emotions drive generosity.

Rejections in the ultimatum game have been shown to be caused by adverse physiologic reactions to stingy offers.[36] In a brain imaging experiment by Sanfey et al., stingy offers (relative to fair and hyperfair offers) differentially activated several brain areas, especially the anterior insular cortex, a region associated with visceral disgust. If Player 1 in the ultimatum game anticipates this response to a stingy offer, they may be more generous.

An increase in rational decisions in the game has been found among experienced Buddhist meditators. fMRI data show that meditators recruit the posterior insular cortex (associated with interoception) during unfair offers and show reduced activity in the anterior insular cortex compared to controls.[37]

People whose serotonin levels have been artificially lowered will reject unfair offers more often than players with normal serotonin levels.[38]

People who have ventromedial frontal cortex lesions were found to be more likely to reject unfair offers.[39] This was suggested to be due to the abstractness and delay of the reward, rather than an increased emotional response to the unfairness of the offer.[40]

Evolutionary game theory

editOther authors have used evolutionary game theory to explain behavior in the ultimatum game.[41][42][43][44][45] Simple evolutionary models, e.g. the replicator dynamics, cannot account for the evolution of fair proposals or for rejections.[46] These authors have attempted to provide increasingly complex models to explain fair behavior.

Sociological applications

editThe ultimatum game is important from a sociological perspective, because it illustrates the human unwillingness to accept injustice. The tendency to refuse small offers may also be seen as relevant to the concept of honour.

The extent to which people are willing to tolerate different distributions of the reward from "cooperative" ventures results in inequality that is, measurably, exponential across the strata of management within large corporations. See also: Inequity aversion within companies.

History

editAn early description of the ultimatum game is by Nobel laureate John Harsanyi in 1961, who footnotes Thomas Schelling's 1960 book, The Strategy of Conflict on its solution by dominance methods. Harsanyi says,[47]

- "An important application of this principle is to ultimatum games, i.e., to bargaining games where one of the players can firmly commit himself in advance under a heavy penalty that he will insist under all conditions upon a certain specified demand (which is called his ultimatum).... Consequently, it will be rational for the first player to commit himself to his maximum demand, i.e., to the most extreme admissible demand he can make."

Josh Clark attributes modern interest in the game to Ariel Rubinstein,[48] but the best-known article is the 1982 experimental analysis of Güth, Schmittberger, and Schwarze.[49] Results from testing the ultimatum game challenged the traditional economic principle that consumers are rational and utility-maximising.[50] This started a variety of research into the psychology of humans.[51] Since the ultimatum game's development, it has become a popular economic experiment, and was said to be "quickly catching up with the Prisoner's Dilemma as a prime showpiece of apparently irrational behavior" in a paper by Martin Nowak, Karen M. Page, and Karl Sigmund.[44]

Variants

editIn the "competitive ultimatum game" there are many proposers and the responder can accept at most one of their offers: With more than three (naïve) proposers the responder is usually offered almost the entire endowment[52] (which would be the Nash Equilibrium assuming no collusion among proposers).

In the "ultimatum game with tipping", a tip is allowed from responder back to proposer, a feature of the trust game, and net splits tend to be more equitable.[53]

The "reverse ultimatum game" gives more power to the responder by giving the proposer the right to offer as many divisions of the endowment as they like. Now the game only ends when the responder accepts an offer or abandons the game, and therefore the proposer tends to receive slightly less than half of the initial endowment.[54]

Incomplete information ultimatum games: Some authors have studied variants of the ultimatum game in which either the proposer or the responder has private information about the size of the pie to be divided.[55][56] These experiments connect the ultimatum game to principal-agent problems studied in contract theory.

The pirate game illustrates a variant with more than two participants with voting power, as illustrated in Ian Stewart's "A Puzzle for Pirates".[57]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Harsanyi, John C. (1961). "On the Rationality Postulates underlying the Theory of Cooperative Games". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 5 (2): 179–196. doi:10.1177/002200276100500205. S2CID 220642229.

- ^ Fudenberg, Drew; Tirole, Jean (1991-04-01). "Perfect Bayesian equilibrium and sequential equilibrium". Journal of Economic Theory. 53 (2): 236–260. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(91)90155-W. ISSN 0022-0531.

- ^ A strategy is an action plan, not an outcome or an action, so the Acceptor's strategy has to say what they would do in every possible circumstance, even though in equilibrium S=0 and S>1 do not happen.

- ^ Güth, Werner; Schmittberger, Rolf; Schwarze, Bernd (1982). "An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining" (PDF). Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 3 (4): 367–388. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7.

- ^ Sanfey, Alan; Rilling; Aronson; Nystrom; Cohen (13 June 2003). "The Neural Basis of Economic Decision-Making in the Ultimatum Game". Science. 300 (5626): 1755–1758. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1755S. doi:10.1126/science.1082976. JSTOR 3834595. PMID 12805551. S2CID 7111382.

- ^ See Henrich, Joseph, Robert Boyd, Samuel Bowles, Colin Camerer, Ernst Fehr, and Herbert Gintis (2004). Foundations of Human Sociality: Economic Experiments and Ethnographic Evidence from Fifteen Small-Scale Societies. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Oosterbeek, Hessel, Randolph Sloof, and Gijs van de Kuilen (2004). "Cultural Differences in Ultimatum Game Experiments: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis". Experimental Economics. 7 (2): 171–188. doi:10.1023/B:EXEC.0000026978.14316.74. S2CID 17659329.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cesarini, D.; Dawes, C. T.; Fowler, J. H.; Johannesson, M.; Lichtenstein, P.; Wallace, B. (2008). "Heritability of cooperative behavior in the trust game". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (10): 3721–3726. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.3721C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710069105. PMC 2268795. PMID 18316737.

- ^ Bosman, Ronald; Sonnemans, Joep; Zeelenberg, Marcel Zeelenberg (2001). "Emotions, rejections, and cooling off in the ultimatum game". Unpublished Manuscript, University of Amsterdam.

- ^ See Grimm, Veronika and F. Mengel (2011). "Let me sleep on it: Delay reduces rejection rates in Ultimatum Games'', Economics Letters, Elsevier, vol. 111(2), pages 113–115, May.

- ^ Oechssler, Jörg; Roider, Andreas; Schmitz, Patrick W. (2015). "Cooling Off in Negotiations: Does it Work?". Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics. 171 (4): 565–588. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.333.5336. doi:10.1628/093245615X14307212950056. S2CID 14646404.

- ^ Proctor, Darby; Williamson; de Waal; Brosnan (2013). "Chimpanzees play the ultimatum game". PNAS. 110 (6): 2070–2075. doi:10.1073/pnas.1220806110. PMC 3568338. PMID 23319633.

- ^ Kaiser, Ingrid; Jensen; Call; Tomasello (2012). "Theft in an ultimatum game: chimpanzees and bonobos are insensitive to unfairness". Biology Letters. 8 (6): 942–945. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.0519. PMC 3497113. PMID 22896269.

- ^ Henrich, Joseph; Boyd, Robert; Bowles, Samuel; Camerer, Colin; Fehr, Ernst; Gintis, Herbert; McElreath, Richard; Alvard, Michael; Barr, Abigail; Ensminger, Jean; Henrich, Natalie Smith; Hill, Kim; Gil-White, Francisco; Gurven, Michael; Marlowe, Frank W.; Patton, John Q.; Tracer, David (December 2005). ""Economic man" in cross-cultural perspective: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 28 (6): 795–815. doi:10.1017/S0140525X05000142. eISSN 1469-1825. ISSN 0140-525X. PMID 16372952. S2CID 3194574.

- ^ Henrich, Joseph; Heine, Steven J.; Norenzayan, Ara (June 2010). "The weirdest people in the world?" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 33 (2–3): 61–83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. eISSN 1469-1825. ISSN 0140-525X. PMID 20550733. S2CID 219338876.

- ^ Murray, Cameron (October 11, 2010). "WEIRD people: Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich, Democratic... and unlike anyone else on the planet". Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Watters, Ethan (June 14, 2017). "We Aren't The World". Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Leliveld, Marijke C.; van Dijk, Eric; van Beest, Ilja (September 2008). "Initial Ownership in Bargaining: Introducing the Giving, Splitting, and Taking Ultimatum Bargaining Game". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 34 (9): 1214–1225. doi:10.1177/0146167208318600. eISSN 1552-7433. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 18587058. S2CID 206443401.

- ^ Lightner, Aaron D.; Barclay, Pat; Hagen, Edward H. (December 2017). "Radical framing effects in the ultimatum game: the impact of explicit culturally transmitted frames on economic decision-making". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (12): 170543. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470543L. doi:10.1098/rsos.170543. eISSN 2054-5703. PMC 5749986. PMID 29308218.

- ^ Bolton, G.E. (1991). "A comparative Model of Bargaining: Theory and Evidence". American Economic Review. 81: 1096–1136.

- ^ Ochs, J. and Roth, A. E. (1989). "An Experimental Study of Sequential Bargaining". American Economic Review. 79: 355–384.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eriksson, Kimmo; Strimling, Pontus; Andersson, Per A.; Lindholm, Torun (2017-03-01). "Costly punishment in the ultimatum game evokes moral concern, in particular when framed as payoff reduction". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 69: 59–64. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2016.09.004. ISSN 0022-1031. S2CID 151549755.

- ^ Nowak, M. A. (2000-09-08). "Fairness Versus Reason in the Ultimatum Game". Science. 289 (5485): 1773–1775. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1773N. doi:10.1126/science.289.5485.1773. PMID 10976075. S2CID 6342076.

- ^ Morewedge, Carey K.; Krishnamurti, Tamar; Ariely, Dan (2014-01-01). "Focused on fairness: Alcohol intoxication increases the costly rejection of inequitable rewards". Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 50: 15–20. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2013.08.006.

- ^ Tabibnia, Golnaz; Satpute, Ajay B.; Lieberman, Matthew D. (2008-04-01). "The Sunny Side of Fairness Preference for Fairness Activates Reward Circuitry (and Disregarding Unfairness Activates Self-Control Circuitry)". Psychological Science. 19 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02091.x. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 18399886. S2CID 15454802.

- ^ a b Mongolian/Kazakh study conclusion from University of Pennsylvania.

- ^ Gil-White, F.J. (2004). "Ultimatum Game with an Ethnicity Manipulation": 260–304.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Harris, Alison; Young, Aleena; Hughson, Livia; Green, Danielle; Doan, Stacey N.; Hughson, Eric; Reed, Catherine L. (2020-01-09). "Perceived relative social status and cognitive load influence acceptance of unfair offers in the Ultimatum Game". PLOS ONE. 15 (1): e0227717. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1527717H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0227717. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6952087. PMID 31917806.

- ^ Social Role in the Ultimate Game

- ^ Bellemare, Charles; Kröger, Sabine; Soest, Arthur Van (2008). "Measuring Inequity Aversion in a Heterogeneous Population Using Experimental Decisions and Subjective Probabilities". Econometrica. 76 (4): 815–839. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0262.2008.00860.x. ISSN 1468-0262. S2CID 55369709.

- ^ Brenner, Thomas; Vriend, Nicholas J. (2006). "On the behavior of proposers in ultimatum games". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 61 (4): 617–631. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.322.733. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2004.07.014.

- ^ Surowieki, James (2005). The Wisdom of Crowds. Anchor.

- ^ Andersen, Steffen; Ertaç, Seda; Gneezy, Uri; Hoffman, Moshe; List, John A (2011). "Stakes Matter in Ultimatum Games". American Economic Review. 101 (7): 3427–3439. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.222.5059. doi:10.1257/aer.101.7.3427. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Zak, P.J., Stanton, A.A., Ahmadi, S. (2007). Brosnan, Sarah (ed.). "Oxytocin Increases Generosity in Humans" (PDF). PLOS ONE. 2 (11): e1128. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1128Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001128. PMC 2040517. PMID 17987115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zak, Paul J.; Stanton, Angela A.; Ahmadi, Sheila (2007-11-07). "Oxytocin Increases Generosity in Humans". PLOS ONE. 2 (11): e1128. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2.1128Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001128. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 2040517. PMID 17987115.

- ^ Sanfey, et al. (2002)

- ^ Kirk; et al. (2011). "Interoception Drives Increased Rational Decision-Making in Meditators Playing the Ultimatum Game". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 5: 49. doi:10.3389/fnins.2011.00049. PMC 3082218. PMID 21559066.

- ^ Crockett, Molly J.; Luke Clark; Golnaz Tabibnia; Matthew D. Lieberman; Trevor W. Robbins (2008-06-05). "Serotonin Modulates Behavioral Reactions to Unfairness". Science. 320 (5884): 1155577. Bibcode:2008Sci...320.1739C. doi:10.1126/science.1155577. PMC 2504725. PMID 18535210.

- ^ Koenigs, Michael; Daniel Tranel (January 2007). "Irrational Economic Decision-Making after Ventromedial Prefrontal Damage: Evidence from the Ultimatum Game". Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (4): 951–956. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4606-06.2007. PMC 2490711. PMID 17251437.

- ^ Moretti, Laura; Davide Dragone; Giuseppe di Pellegrino (2009). "Reward and Social Valuation Deficits following Ventromedial Prefrontal Damage". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 21 (1): 128–140. doi:10.1162/jocn.2009.21011. PMID 18476758. S2CID 42852077.

- ^ Gale, J., Binmore, K.G., and Samuelson, L. (1995). "Learning to be Imperfect: The Ultimatum Game". Games and Economic Behavior. 8: 56–90. doi:10.1016/S0899-8256(05)80017-X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Güth, W.; Yaari, M. (1992). "An Evolutionary Approach to Explain Reciprocal Behavior in a Simple Strategic Game". In U. Witt (ed.). Explaining Process and Change – Approaches to Evolutionary Economics. Ann Arbor. pp. 23–34.

- ^ Huck, S.; Oechssler, J. (1999). "The Indirect Evolutionary Approach to Explaining Fair Allocations". Games and Economic Behavior. 28: 13–24. doi:10.1006/game.1998.0691. S2CID 18398039.

- ^ a b Nowak, M. A.; Page, K. M.; Sigmund, K. (2000). "Fairness Versus Reason in the Ultimatum Game" (PDF). Science. 289 (5485): 1773–1775. Bibcode:2000Sci...289.1773N. doi:10.1126/science.289.5485.1773. PMID 10976075. S2CID 6342076.

- ^ Skyrms, B. (1996). Evolution of the Social Contract. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Forber, Patrick; Smead, Rory (7 April 2014). "The evolution of fairness through spite". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 281 (1780): 20132439. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.2439. PMC 4027385. PMID 24523265. S2CID 11410542.

- ^ Harsanyi, John C. (1961). "On the Rationality Postulates underlying the Theory of Cooperative Games". The Journal of Conflict Resolution. 5 (2): 367–196. doi:10.1177/002200276100500205. S2CID 220642229.

- ^ Rubinstein, Ariel (1961). "What's the ultimatum game?". HowStuffWorks.

- ^ Güth, W., Schmittberger, and Schwarze (1982). "An Experimental Analysis of Ultimatum Bargaining" (PDF). Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization. 3 (4): 367–388. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(82)90011-7.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), page 367: the description of the game at Neuroeconomics cites this as the earliest example. - ^ van Damme, Eric; Binmore, Kenneth G.; Roth, Alvin E.; Samuelson, Larry; Winter, Eyal; Bolton, Gary E.; Ockenfels, Axel; Dufwenberg, Martin; Kirchsteiger, Georg; Gneezy, Uri; Kocher, Martin G. (2014-12-01). "How Werner Güth's ultimatum game shaped our understanding of social behavior". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 108: 292–293. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2014.10.014. ISSN 0167-2681.

- ^ van Damme, Eric; Binmore, Kenneth G.; Roth, Alvin E.; Samuelson, Larry; Winter, Eyal; Bolton, Gary E.; Ockenfels, Axel; Dufwenberg, Martin; Kirchsteiger, Georg; Gneezy, Uri; Kocher, Martin G. (2014-12-01). "How Werner Güth's ultimatum game shaped our understanding of social behavior". Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization. 108: 310–313. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2014.10.014. ISSN 0167-2681.

- ^ Ultimatum game with proposer competition by the GameLab.

- ^ Ruffle, B.J. (1998). "More is Better, but Fair is Fair: Tipping in Dictator and Ultimatum Games". Games and Economic Behavior. 23 (2): 247–265. doi:10.1006/game.1997.0630. S2CID 9091550., p. 247.

- ^ The reverse ultimatum game and the effect of deadlines is from Uri Gneezy, Ernan Haruvy, and Roth, A. E. (2003). "Bargaining under a deadline: evidence from the reverse ultimatum game" (PDF). Games and Economic Behavior. 45 (2): 347–368. doi:10.1016/S0899-8256(03)00151-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 31, 2004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitzkewitz, Michael; Nagel, Rosemarie (1993). "Experimental results on ultimatum games with incomplete information". International Journal of Game Theory. 22 (2): 171–198. doi:10.1007/BF01243649. ISSN 0020-7276. S2CID 120136865.

- ^ Hoppe, Eva I.; Schmitz, Patrick W. (2013). "Contracting under Incomplete Information and Social Preferences: An Experimental Study". The Review of Economic Studies. 80 (4): 1516–1544. doi:10.1093/restud/rdt010. ISSN 0034-6527.

- ^ Stewart, Ian (May 1999). "A Puzzle for Pirates" (PDF). Scientific American. 280 (5): 98–99. Bibcode:1999SciAm.280e..98S. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0599-98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27.

Further reading

edit- Stanton, Angela (2006). "Evolving Economics: Synthesis".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Binmore, Ken (2007). "The Ultimatum Game". Does Game Theory Work?. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp. 103–117. ISBN 978-0-262-02607-9.

- Alvard, M. (2004). "The Ultimatum Game, Fairness, and Cooperation among Big Game Hunters" (PDF). In Henrich, J.; Boyd, R.; Bowles, S.; Gintis, H.; Fehr, E.; Camerer, C. (eds.). Foundations of Human Sociality: Ethnography and Experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Oxford University Press. pp. 413–435.

- Bearden, J. Neil (2001). "Ultimatum Bargaining Experiments: The State of the Art". SSRN 626183.

- Bicchieri, Cristina and Jiji Zhang (2008). "An Embarrassment of Riches: Modeling Social Preferences in Ultimatum games", in U. Maki (ed) Handbook of the Philosophy of Economics, Elsevier