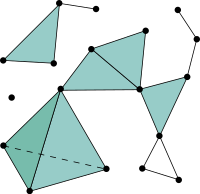

In mathematics, a simplicial complex is a set composed of points, line segments, triangles, and their n-dimensional counterparts (see illustration). Simplicial complexes should not be confused with the more abstract notion of a simplicial set appearing in modern simplicial homotopy theory. The purely combinatorial counterpart to a simplicial complex is an abstract simplicial complex. To distinguish a simplicial complex from an abstract simplicial complex, the former is often called a geometric simplicial complex.[1]: 7

Definitions

editA simplicial complex is a set of simplices that satisfies the following conditions:

- 1. Every face of a simplex from is also in .

- 2. The non-empty intersection of any two simplices is a face of both and .

See also the definition of an abstract simplicial complex, which loosely speaking is a simplicial complex without an associated geometry.

A simplicial k-complex is a simplicial complex where the largest dimension of any simplex in equals k. For instance, a simplicial 2-complex must contain at least one triangle, and must not contain any tetrahedra or higher-dimensional simplices.

A pure or homogeneous simplicial k-complex is a simplicial complex where every simplex of dimension less than k is a face of some simplex of dimension exactly k. Informally, a pure 1-complex "looks" like it's made of a bunch of lines, a 2-complex "looks" like it's made of a bunch of triangles, etc. An example of a non-homogeneous complex is a triangle with a line segment attached to one of its vertices. Pure simplicial complexes can be thought of as triangulations and provide a definition of polytopes.

A facet is a maximal simplex, i.e., any simplex in a complex that is not a face of any larger simplex.[2] (Note the difference from a "face" of a simplex). A pure simplicial complex can be thought of as a complex where all facets have the same dimension. For (boundary complexes of) simplicial polytopes this coincides with the meaning from polyhedral combinatorics.

Sometimes the term face is used to refer to a simplex of a complex, not to be confused with a face of a simplex.

For a simplicial complex embedded in a k-dimensional space, the k-faces are sometimes referred to as its cells. The term cell is sometimes used in a broader sense to denote a set homeomorphic to a simplex, leading to the definition of cell complex.

The underlying space, sometimes called the carrier of a simplicial complex, is the union of its simplices. It is usually denoted by or .

Support

editThe relative interiors of all simplices in form a partition of its underlying space : for each point , there is exactly one simplex in containing in its relative interior. This simplex is called the support of x and denoted .[3]: 9

Closure, star, and link

edit-

Two simplices and their closure.

-

A vertex and its star.

-

A vertex and its link.

Let K be a simplicial complex and let S be a collection of simplices in K.

The closure of S (denoted ) is the smallest simplicial subcomplex of K that contains each simplex in S. is obtained by repeatedly adding to S each face of every simplex in S.

The star of S (denoted ) is the union of the stars of each simplex in S. For a single simplex s, the star of s is the set of simplices in K that have s as a face. The star of S is generally not a simplicial complex itself, so some authors define the closed star of S (denoted ) as the closure of the star of S.

The link of S (denoted ) equals . It is the closed star of S minus the stars of all faces of S.

Algebraic topology

editIn algebraic topology, simplicial complexes are often useful for concrete calculations. For the definition of homology groups of a simplicial complex, one can read the corresponding chain complex directly, provided that consistent orientations are made of all simplices. The requirements of homotopy theory lead to the use of more general spaces, the CW complexes. Infinite complexes are a technical tool basic in algebraic topology. See also the discussion at Polytope of simplicial complexes as subspaces of Euclidean space made up of subsets, each of which is a simplex. That somewhat more concrete concept is there attributed to Alexandrov. Any finite simplicial complex in the sense talked about here can be embedded as a polytope in that sense, in some large number of dimensions. In algebraic topology, a compact topological space which is homeomorphic to the geometric realization of a finite simplicial complex is usually called a polyhedron (see Spanier 1966, Maunder 1996, Hilton & Wylie 1967).

Combinatorics

editCombinatorialists often study the f-vector of a simplicial d-complex Δ, which is the integer sequence , where fi is the number of (i−1)-dimensional faces of Δ (by convention, f0 = 1 unless Δ is the empty complex). For instance, if Δ is the boundary of the octahedron, then its f-vector is (1, 6, 12, 8), and if Δ is the first simplicial complex pictured above, its f-vector is (1, 18, 23, 8, 1). A complete characterization of the possible f-vectors of simplicial complexes is given by the Kruskal–Katona theorem.

By using the f-vector of a simplicial d-complex Δ as coefficients of a polynomial (written in decreasing order of exponents), we obtain the f-polynomial of Δ. In our two examples above, the f-polynomials would be and , respectively.

Combinatorists are often quite interested in the h-vector of a simplicial complex Δ, which is the sequence of coefficients of the polynomial that results from plugging x − 1 into the f-polynomial of Δ. Formally, if we write FΔ(x) to mean the f-polynomial of Δ, then the h-polynomial of Δ is

and the h-vector of Δ is

We calculate the h-vector of the octahedron boundary (our first example) as follows:

So the h-vector of the boundary of the octahedron is (1, 3, 3, 1). It is not an accident this h-vector is symmetric. In fact, this happens whenever Δ is the boundary of a simplicial polytope (these are the Dehn–Sommerville equations). In general, however, the h-vector of a simplicial complex is not even necessarily positive. For instance, if we take Δ to be the 2-complex given by two triangles intersecting only at a common vertex, the resulting h-vector is (1, 3, −2).

A complete characterization of all simplicial polytope h-vectors is given by the celebrated g-theorem of Stanley, Billera, and Lee.

Simplicial complexes can be seen to have the same geometric structure as the contact graph of a sphere packing (a graph where vertices are the centers of spheres and edges exist if the corresponding packing elements touch each other) and as such can be used to determine the combinatorics of sphere packings, such as the number of touching pairs (1-simplices), touching triplets (2-simplices), and touching quadruples (3-simplices) in a sphere packing.

Computational problems

editThe simplicial complex recognition problem is: given a finite simplicial complex, decide whether it is homeomorphic to a given geometric object. This problem is undecidable for any d-dimensional manifolds for d ≥ 5.

See also

edit- Abstract simplicial complex

- Barycentric subdivision

- Causal dynamical triangulation

- Delta set

- Loop quantum gravity

- Polygonal chain – 1 dimensional simplicial complex

- Tucker's lemma

- Simplex tree

References

edit- ^ Matoušek, Jiří (2007). Using the Borsuk-Ulam Theorem: Lectures on Topological Methods in Combinatorics and Geometry (2nd ed.). Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-00362-5.

Written in cooperation with Anders Björner and Günter M. Ziegler

, Section 4.3 - ^ De Loera, Jesús A.; Rambau, Jörg; Santos, Francisco (2010), Triangulations: Structures for Algorithms and Applications, Algorithms and Computation in Mathematics, vol. 25, Springer, p. 493, ISBN 9783642129711.

- ^ Matoušek, Jiří (2007). Using the Borsuk-Ulam Theorem: Lectures on Topological Methods in Combinatorics and Geometry (2nd ed.). Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-00362-5.

Written in cooperation with Anders Björner and Günter M. Ziegler

, Section 4.3

- Spanier, Edwin H. (1966), Algebraic Topology, Springer, ISBN 0-387-94426-5

- Maunder, Charles R.F. (1996), Algebraic Topology (Reprint of the 1980 ed.), Mineola, NY: Dover, ISBN 0-486-69131-4, MR 1402473

- Hilton, Peter J.; Wylie, Shaun (1967), Homology Theory, New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-09422-4, MR 0115161