Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens

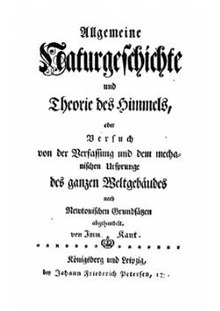

Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens (German: Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels), subtitled or an Attempt to Account for the Constitutional and Mechanical Origin of the Universe upon Newtonian Principles,[a] is a work written and published anonymously by Immanuel Kant in 1755.

| |

| Author | Immanuel Kant |

|---|---|

| Original title | Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels |

| Language | German |

| Subject | cosmogony |

| Published | 1755 |

| Publication place | Germany |

| Media type | |

According to Kant, the Solar System is merely a smaller version of the fixed star systems, such as the Milky Way and other galaxies. The cosmogony that Kant proposes is closer to today's accepted ideas than that of some of his contemporary thinkers, such as Pierre-Simon Laplace. Moreover, Kant's thought in this volume is strongly influenced by the atomist theory, in addition to the ideas of Lucretius.

Background

editKant had read a 1751 review of Thomas Wright's An Original Theory or New Hypothesis of the Universe (1750), and he credited this with inspiring him in writing the Universal Natural History.[1]

Kant answered to the call of the Berlin Academy Prize in 1754[2] with the argument that the Moon's gravity would eventually cause its tidal locking to coincide with the Earth's rotation. The next year, he expanded this reasoning to the formation and evolution of the Solar System in the Universal Natural History.[3]

Within the work Kant quotes Pierre Louis Maupertuis, who discusses six bright celestial objects listed by Edmond Halley, including Andromeda. Most of these are nebulae, but Maupertuis notes that about one-fourth of them are collections of stars—accompanied by white glows which they would be unable to cause on their own. Halley points to light created before the birth of the Sun, while William Derham "compares them to openings through which shines another immeasurable region and perhaps the fire of heaven." He also observed that the collections of stars were much more distant than stars observed around them. Johannes Hevelius noted that the bright spots were massive and were flattened by a rotating motion; they are in fact galaxies.

Contents

editKant proposes the nebular hypothesis, in which solar systems are the result of nebulae (interstellar clouds of dust) coalescing into accretion disks and then forming suns and their planets.[4] He also discusses comets, and postulates that the Milky Way is only one of many galaxies.[1]

In a speculative proposal, Kant argues that the Earth could have once had a ring around it like the rings of Saturn. He correctly theorizes that the latter are made up of individual particles, likely made of ice.[1] He cites the hypothetical ring as a possible explanation for "the water upon the firmament" described in the Genesis creation narrative as well as a source of water for its flood narrative.[1]

Kant's book ends with an almost mystical expression of appreciation for nature: "In the universal silence of nature and in the calm of the senses the immortal spirit's hidden faculty of knowledge speaks an ineffable language and gives [us] undeveloped concepts, which are indeed felt, but do not let themselves be described."[5]

Translations

editThe first English translation of the work was done by the Scottish theologian William Hastie, in 1900.[6] Other English translations include those by Stanley Jaki and Ian Johnston.[7]

Criticism

editIn his introduction to the English translation of Kant's book, Stanley Jaki criticises Kant for being a poor mathematician and downplays the relevance of his contribution to science. However, Stephen Palmquist argued that Jaki's criticisms are biased and "[a]ll he has shown ... is that the Allgemeine Naturgeschichte does not meet the rigorous standards of the twentieth-century historian of science."[8]

References

editFootnotes

Citations

- ^ a b c d Sagan, Carl & Druyan, Ann (1997). Comet. New York: Random House. pp. 83–84, 86. ISBN 978-0-3078-0105-0.

- ^ Manfred Kühn, Kant - A Biography, CUP, 2002), p. 98: "[The essay] entitled "Investigation of the Question whether the Earth Has Experienced a Change in Its Rotation" [...] was meant to answer a question formulated for a public competition by the Berlin Academy. Though the deadline was at first 1754, the Academy extended it on 6 June 1754, for another two years. When Kant decided to publish this essay, he did not know of the extension. Kant claimed that he could not have achieved the kind of perfection required for winning the prize because he restricted himself to the "physical aspect" of the question."

- ^ Brush, Stephen G. (28 May 2014). A History of Modern Planetary Physics: Nebulous Earth. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0521441711.

- ^ Woolfson, M.M. (1993). "Solar System – its origin and evolution". Q. J. R. Astron. Soc. 34: 1–20. Bibcode:1993QJRAS..34....1W.

- ^ Immanuel Kant, Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens, p.367; translated by Stephen Palmquist in Kant's Critical Religion (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), p.320.

- ^ Michael J. Crowe (1999). The Extraterrestrial Life Debate, 1750-1900. Courier Dover Publications. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-486-40675-6.

- ^ Immanuel Kant (2012). Eric Watkins (ed.). Kant: Natural Science. Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-521-36394-5.

- ^ Stephen Palmquist, "Kant's Cosmogony Re-Evaluated", Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 18:3 (September 1987), pp.255–269.

External links

edit- "Online version of the text". Vancouver Island University (in German).

- "English translation". Vancouver Island University.