Indiana World War Memorial Plaza

The Indiana World War Memorial Plaza is an urban feature and war memorial located in downtown Indianapolis, Indiana, United States, originally built to honor the veterans of World War I.[3] It was conceived in 1919 as a location for the national headquarters of the American Legion and a memorial to the state's and nation's veterans.

Indiana War Memorial Plaza | |

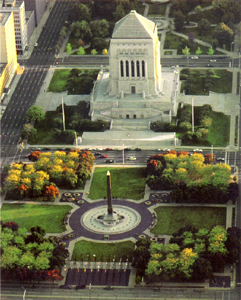

Aerial view of the plaza looking south | |

| Location | Bounded by St. Clair, Pennsylvania, Vermont, and Meridian Sts., Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°46′25″N 86°9′25″W / 39.77361°N 86.15694°W |

| Built | 1924 |

| Architect | Walker & Weeks; Henry Hering |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts, Neoclassical |

| NRHP reference No. | 89001404[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 25, 1989 |

| Boundary increase | December 23, 2016 |

| Designated NHLD | October 11, 1994[2] |

The original five-block plaza is bounded by Meridian Street (west), St. Clair Street (north), Pennsylvania Street (east), and New York Street (south). American Legion Mall comprises the two northernmost blocks and is home to the Legion's administrative buildings and a cenotaph. Veterans Memorial Plaza, with its obelisk, forms the third block. The plaza's focal point, the Indiana World War Memorial, is located on the fourth block. Modeled after the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, it houses a military museum and auditorium.[4] The fifth and southernmost block is University Park, home to statues and a fountain.[5]

On October 11, 1994, the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza was designated a National Historic Landmark District. In 2016, the district was enlarged to include in its scope the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument and was renamed the Indiana World War Memorial Historic District. Combined, it is the largest war memorial project in the United States,[6] encompassing 24 acres (9.7 ha).[7]

History

editThe origins of the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza lay in a 1919 attempt by the city of Indianapolis to lure the newly formed American Legion from its temporary headquarters in New York City. The American Legion, chartered by Congress following World War I, is an organization of veterans that sponsors youth programs, promotes patriotism and national security and provides a commitment to Americans who have served in the armed forces.[8]

At an American Legion national convention in Minneapolis in November 1919, cities sent representatives to lobby to become the new headquarters. Indianapolis drew support because of its central location within the United States and the city's shows of patriotism. Although Washington, D.C. received the most votes on the first ballot, Indianapolis gained a majority and won the second with 361 votes of 684 cast.[3]

The city and state then had to provide a location, and one of the promises the city made was to erect a fitting memorial to those who served in World War I. Thus, in January 1920 a public library, St. Clair Park, University Park, and two occupied city blocks were designated as the site for the plaza, with one new building for the American Legion to use as their national headquarters, various public buildings, and a war memorial. The Indiana War Memorial Bill was passed in July 1920 and appropriated $2 million for construction and land.[3] The city and state reached an agreement whereby the city would pay for the site and maintenance costs, while the State of Indiana would pay for the memorial's construction.[9] The Plaza was dedicated by the Legion in November 1921 with the laying of a cornerstone from the bridge over the River Marne at Château-Thierry. About 45 buildings on the blocks were demolished in 1926, though several were relocated, and the Second Presbyterian Church and the First Baptist Church were not demolished until 1960.[10][11]

Various architects were invited by an appointed War Memorial Board, led by professional advisor and trustee Thomas Rogers Kimball,[12] to submit designs for a memorial intended to honor all who fought in World War I and also to provide meeting places, archives, and offices for the American Legion. Cleveland, Ohio-based Walker and Weeks was selected in 1923. Their plan consisted of a central memorial and two auxiliary buildings, an obelisk, a mall, and a cenotaph. Bids for the American Legion building, one of the two auxiliary buildings, were put out in 1925, and construction by the Craig-Curtiss Company began the same year.[3] The buildings were neoclassical in design to complement the existing Central Library and U.S. Courthouse and Post Office; completed before the plaza's development, the buildings anchor the north and south ends of the plaza, respectively. The second auxiliary building was not constructed until 1950.[9] When Congress authorized the payment of World War I veterans' bonuses in 1936, the state of Indiana used the money for the construction of the memorial plaza, rather than paying it to the veterans.[13] One additional building was planned but never built.[3]

Indiana World War Memorial Plaza's buildings and greenspaces exemplify City Beautiful movement design principles organized on classical, uniform, and beautiful public architecture.[14] In 1989, the plaza was listed on the National Register of Historic Places and was named a National Historic Landmark District in 1994.[1] The historic district boundaries have expanded to include additional off-site memorials dedicated in recent years, including the USS Indianapolis CA-35 Memorial (1995), Medal of Honor Memorial (1999), and Indiana 9/11 Memorial (2011).[7]

Indiana World War Memorial Plaza is a frequent host to civic events and military services, namely the national observances of Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Veterans Day.[4] It has been the site of numerous festivals, including Indiana Black Expo's Heritage Music Festival[15] and Indy Pride.[16] The plaza served as the site of the National Sports Festival IV opening ceremonies in 1982.[17]

American Legion Mall

editAmerican Legion Mall covers the two northernmost blocks of the five-block civic center. The mall is bounded by Meridian Street (west), St. Clair Street (north), Pennsylvania Street (east), and North Street (south). Prior to its construction, the south block of the mall was home to the Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired.[4]

The two auxiliary buildings on the plaza are used by the American Legion. Both buildings were constructed from Indiana limestone in neoclassical style, consistent with the Indianapolis Central Library to the north. Until 2014, the west building fronting Meridian Street served as the Indiana Veteran's Support Center.[18] The larger east building fronting Pennsylvania Street serves as the Legion's national headquarters, housing mail services, archives, and other internal administrative functions of the Legion; the lobbying efforts of the Legion are based in its Washington, D.C. office.[19] Its two wings are joined by a recessed central entrance.[3]

The Vietnam and Korean Wars Memorial (1996) consist of two semi-circular limestone and granite monuments divided proportionally to represent the number of casualties from each conflict. Both monuments are engraved with the names of Hoosiers killed in the Korean War and Vietnam War along with excerpts from letters home.[20] The World War II Memorial (1998) is a single cylindrical limestone monument engraved with the names of Hoosier World War II casualties. A free-standing column lists operations and campaigns of the war. Both memorials were designed by architect Patrick Brunner.[20][21][4] The Gold Star Families Memorial Monument, situated in the northeast quadrant of the mall, was dedicated on May 1, 2021.[22]

Cenotaph Square

editCenotaph Square is situated between the two auxiliary buildings, south of the Central Library, and to the north of the sunken garden. The rectangular black granite cenotaph centered in it rests upon a base of red and dark green granite. Four shafts of black granite topped with gold eagles mark the corners of the square.[9]

The inscription on the north face of the cenotaph memorializes James Bethel Gresham, a Hoosier who was the first member of the American Expeditionary Force to be killed in action in World War I.[14] A native of Evansville, Indiana, he was a corporal in the 16th Infantry Regiment and was killed at Bathelémont, France, on November 3, 1917. The inscription on the south side reads "A tribute by Indiana to the hallowed memory of the glorious dead who served in the World War."[23]

Veterans Memorial Plaza

editThe Veterans Memorial Plaza, also called Obelisk Square, is located on the third block, south of American Legion Mall.[9] The 100-foot (30 m) black granite obelisk was built in 1923 and the square was completed in 1930.[24] Near the base of the obelisk are 4-foot (1.2 m)-by-8-foot (2.4 m) panels placed in 1929 representing law, science, religion, and education intended to represent the fundamentals of the nation. The obelisk rises from a 100-foot-diameter (30 m), two-level fountain made of pink Georgia marble and terrazzo.[3][25] The fountain has two basins, spray rings, and multicolored lights.[9]

The square was originally paved with asphalt, but it was landscaped with grass and trees in 1975.[3] On the east and west sides fly the flags of the fifty states, which were installed in 1976 in commemoration of the US Bicentennial.[14] They were replaced with the flags of countries of the Americas during the 1987 Pan American Games.[26]

War Memorial building

editArchitects Walker and Weeks planned the Indiana World War Memorial building as the plaza's centerpiece, sited between the federal building and the public library.[14] Work on the actual memorial to the veterans of World War I began in early 1926. Five of the seven buildings located on the site had to be demolished before the construction commenced; the other two, Second Presbyterian Church and First Baptist Church, were not demolished until 1960. General John Pershing laid the cornerstone of the memorial on July 4, 1927, saying he was "consecrating the edifice as a patriotic shrine".[27] Funding problems in 1928 slowed the building of the interior. Even a new contractor in 1931 and $195,000 provided by the Public Works Administration in 1936 did little to speed the process of completing the structure.[9] Although its interior was incomplete, it was dedicated on November 11, 1933 (Veterans Day) by Governor Paul McNutt and Lt. Gen. Hugh Drum, Deputy Chief of Staff of the United States Army.[3] In 1949, a local newspaper reported that the memorial was already deteriorating, its limestone scaling, paint peeling, leaks forming, and plaster cracking; further reports were published in 1961. Despite proposals to develop the area instead of completing it as originally planned, the memorial and surrounding landscaping were finally completed in 1965.[3][9]

The memorial's design is based upon the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. At 210 feet (64 m) tall,[28] it is approximately 75 feet (23 m) taller than the original mausoleum. The blue lights that shine between columns on the side of the War Memorial make the monument easily recognizable. It is the most imposing neoclassical structure in Indianapolis due to its scale and size.[9]

The cubical structure is clad in unrelieved ashlar Indiana limestone on a high, lightly rusticated base, and is topped with a low pyramidal roof that sheathes its interior dome. It stands on a raised terrace approached by a wide monumental staircase. The structure has four identical faces. On each face, an Ionic screen of six columns, behind which are tall banks of windows, and is surmounted by symbolic standing figures designed by Henry Hering: Courage, Memory, Peace, Victory, Liberty, and Patriotism. The sculptures are repeated on each façade. On the south side, standing on a pink granite base in the center of the grand access stairs, is Hering's colossal exultant male nude bronze Pro Patria (1929); it is 24 feet (7.3 m) high, weighs seven tons, and was the largest cast bronze sculpture in the United States.[29]

The north and south entrances are guarded by shield-bearing limestone lions, and on each corner of the terrace sits an urn. The pyramidal roof is stepped and has a lantern on top. Above the tall bronze doors on each side is the inscription "To vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the world."[3] On the north side is the building's main inscription:

To commemorate the valor and sacrifice of the land, sea and air forces of the United States and all who rendered faithful and loyal service at home and overseas in the World War; to inculcate a true understanding and appreciation of the privileges of American citizenship; to inspire patriotism and respect for the laws to the end that peace may prevail, justice be administered, public order maintained and liberty perpetuated.[3]

The memorial hosted 156,241 visitors in 2019.[30]

Indiana War Memorial Museum

editThe main entrance of the Indiana War Memorial Museum[31] is on the north façade, which opens into a large hall with Tennessee marble floors and Art Deco Egyptian themes. The museum is housed mainly on the lower level of the monument and honors the efforts of Hoosier soldiers in a timeline from the American Revolutionary War to modern conflicts. World War I and World War II are featured most prominently. Aside from firearms, it features a Cobra helicopter and the USS Indiana's commission plate. There are over 400 military flags housed in the museum, more than 300 of which are from the American Civil War. Indiana's Liberty Bell replica is located near the main entrance. It is of the kind given to each state by the federal government in 1950 to encourage the purchase of savings bonds.[32]

Additional museum exhibits are displayed on the main level of the monument. An exhibit replicating the radio room of the USS Indianapolis includes original equipment from World War II was opened on November 7, 2009.[33] The Grand Foyer main level features the 500-seat Pershing Auditorium, built and decorated with materials donated from several states and World War I allies. The memorial also has three meeting rooms on the main level; these rooms were originally named in honor of General George Patton, General Douglas MacArthur, and Admiral Chester Nimitz. In 2009, the rooms were renamed in honor of Hoosier veterans: Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, General David M. Shoup, and Major Samuel Woodfill.[34]

Above the main level is the Shrine Room, nearly a vertical double cube, 110 ft (34 m) high and 60 ft (18 m) on a side, clad in materials collected from all the allied nations of World War I. Accessed by two staircases from the Grand Foyer, the Shrine Room Stairway's American Pavonazzo marble walls bear the names of all Hoosiers who fought in World War I. On the east and west sides are paintings by Walter Brough of the leading soldiers of France, America, Great Britain, Belgium, Italy, and Serbia. Surrounding the room are sculptor Frank Jirouch's plaster frieze depicting events of World War I.[3] At the center of the space, beneath a giant hanging 17-foot (5.2 m)-by-30-foot (9.1 m) American flag, is the Altar of Consecration, flanked at the corners with cauldrons on tripod stands. Above the flag is the Star of Destiny, made of Swedish crystal, representing the future of the nation.[3]

Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum

editIn December 2021, the Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum reopened in new quarters in the War Memorial building. The museum had formerly been housed for almost 20 years three blocks south in the basement of the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument, but water leakage there forced the removal of all artifacts in 2018. The War Memorial space is larger, allowing more artifacts to be displayed, and includes American Civil War items from the Military Museum collection.[35]

University Park

editUniversity Park occupies the southernmost block of the plaza, bounded by Meridian Street (west), Vermont Street (north), Pennsylvania Street (east), and New York Street (south). The park was originally reserved for a state university in 1827; however, it became the site of a seminary, the city's first high school, and a training ground for Union troops during the American Civil War. In 1876, the site was designated a public park. In 1914, the park was redesigned by landscape architect George Kessler as part of the park and boulevard system plan commissioned by the city.[14][5]

Among the park's features are three statues of prominent Hoosiers. The Colfax Memorial (1887) is located east of Depew Memorial Fountain and was designed by Lorado Taft.[14] Benjamin Harrison (1908) was designed by Henry Bacon and Charles Niehaus and is located at the south end of the park facing New York Street. The statue of Abraham Lincoln (1934), located at the park's southeast corner, was designed by Henry Hering.[5] Other sculptures include Syrinx (1973) by Adolph Wolter[36] and Pan (1980) by Roger White.[37] Other features include benches, tree plantings,[5] and street lamps designed with acorn globes and fluted shafts. Two of the lamps are decorated with lions' heads standing on the backs of metal turtles.[3]

Depew Memorial Fountain

editThe Depew Memorial Fountain is a free-standing fountain completed in 1919. It is composed of multiple bronze figures arranged on a five-tier granite stone base with three basins. The bronze sculptures depict fish, eight children dancing, and a woman on the topmost tier dancing and playing cymbals.

The fountain was commissioned in memory of Dr. Richard J. Depew by his wife, Emma Ely, following Dr. Depew's death in 1887. When Mrs. Depew died in 1913, she had bequeathed $50,000 from her estate to the city of Indianapolis for the erection of a fountain in memory of her husband "in some park or public place where all classes of people may enjoy it."[38] The original design was created by Karl Bitter, who was killed in a traffic accident in 1915 before the work could be finished. Following Bitter's overall design, Alexander Stirling Calder created the bronze figures and the fountain. Architect Henry Bacon designed the fountain's setting.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Indiana World War Memorial Plaza Historic District". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved August 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rollins, Suzanne T.; Martin, Katherine; Downey, Lawrence; Goetzman, Bruce E. (June 24, 1994). "National Historic Landmark Nomination: Indiana World War Memorial Plaza Historic District" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 6, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2016. and Accompanying seven photos from 1994(PDF)

- ^ a b c d Rollins Stanis, Suzanne T.; Glass, James A. (2021) [1994]. "Indiana World War Memorial Plaza" (website). Digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indianapolis Public Library. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Rollins Stanis, Suzanne T. (2021) [1994]. "University Park" (website). Digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indianapolis Public Library. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ MacLeod, James (May 22, 2015). "World War I's Heart Is Kept in the Heartland". What It Means to be American. The Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Dawn (May 25, 2015). "Monumental Indianapolis: Touring Indianapolis memorials". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "About The American Legion". The American Legion. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bodenhamer, David J. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indiana University Press. pp. 762–763. ISBN 978-0-253-31222-8. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ^ Mitchell, Dawn. "How Indianapolis buildings were moved to make way for the Indiana War Memorial Plaza". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Fujawa, Ed (December 28, 2022). "Structural 'Wanderlust': The Relocation of the Bobbs-Merrill Building". Class 900 Indy. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ "War Memorial Plans", The Indianapolis News, Tuesday, November 28, 1922, p6

- ^ p. 192, Paying with Their Bodies: American War and the Problem of the Disabled Veteran, John M. Kinder

- ^ a b c d e f "Indiana World War Memorial Plaza Historic District". Indianapolis: Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ Drenon, Brandon (July 7, 2022). "Indiana Black Expo's 51st annual Summer Celebration is here. What you need to know". The Indianapolis Star. Archived from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ Opsahl, Sam (July 2021). "Indy Pride" (website). Digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indianapolis Public Library. Archived from the original on May 18, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ Delores J., Wright (2021) [1994]. "National Sports Festival IV" (website). Digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indianapolis Public Library. Archived from the original on October 8, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ Rumer, Thomas A.; Van Allen, Elizabeth J. (2021) [1994]. "American Legion Department of Indiana" (website). Digital Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Indianapolis Public Library. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ Bodenhamer p. 254

- ^ a b "Korean War Memorial". IndyArtsGuide.org. Arts Council of Indianapolis. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "World War II Memorial". IndyArtsGuide.org. Arts Council of Indianapolis. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ Lawson, Michele (May 18, 2021). "Childress family recognized at Gold Star Families Memorial dedication". Tribune Star. Terre Haute, Indiana. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "Indiana World War Memorial - Indianapolis, Indiana". Waymarking. September 14, 2009. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Caldwell, Howard; Jones, Darryl (1990). Goodall, Kenneth (ed.). Indianapolis. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-253-32998-1. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

- ^ Paul, Cindy (December 30, 2008). "Veterans Memorial Plaza: A Stirring Tribute". Fun City Finder. Archived from the original on February 19, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2010.

- ^ The Games of August: Official Commemorative Book. Indianapolis: Showmasters. 1987. ISBN 978-0-9619676-0-4.

- ^ Price, Nelson (2004). Indianapolis Then & Now. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay Press. pp. 102–3. ISBN 1-59223-208-6.

- ^ "Indiana World War Memorial". Emporis. STR Germany GmbH. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Indiana War Memorial Exterior - Pro Patria". State of Indiana. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ "Most Popular Indianapolis-Area Attractions". Indianapolis Business Journal. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved November 15, 2020.

- ^ Indiana War Memorial Museum Archived June 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine. State of Indiana official website. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ "Replicas of the Liberty Bell Owned by US State Governments". Liberty Bell Museum. Archived from the original on May 30, 2008. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ^ "Indiana War Memorials Latest News". State of Indiana. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ "Indiana War Memorial renames rooms for state heroes". Chesterton Tribune. June 10, 2009. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ King, Mason (December 6, 2021). "Civil War Museum relaunches in expanded form in Indiana War Memorial". Indianapolis Business Journal. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ^ "Syrinx". IndyArtsGuide.org. Arts Council of Indianapolis. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ "Pan". IndyArtsGuide.org. Arts Council of Indianapolis. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ Arnold, Laura. "History of the Hoffman House and the Chatham-Arch Historic District". Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

External links

edit- National Park Service site on the Indiana World War Memorial Plaza

- Indiana War Memorial Museum

- Indiana War Memorial Plaza Historic District