Uranium mining in the United States produced 224,331 pounds (101.8 tonnes) of U3O8 in 2023, 15% of the 2018 production of 1,447,945 pounds (656.8 tonnes) of U3O8. The 2023 production represents 0.4% of the uranium fuel requirements of the US's nuclear power reactors for the year. Production came from five in-situ leaching plants, four in Wyoming (Nichols Ranch ISR Project, Lance Project, Lost Creek Project, and Smith Ranch-Highland Operation) and one in Nebraska (Crowe Butte Operation); and from the White Mesa conventional mill in Utah.[1][2][3]

From 1949 to 2019, total US production of uranium oxide (U3O8) was 979.9 million pounds (444,500 tonnes).[2]

History

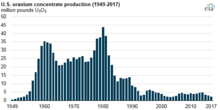

editWhile uranium is used primarily for nuclear power, uranium mining had its roots in the production of radium-bearing ore from 1898 from the mining of uranium-vanadium sandstone deposits in western Colorado. The 1950s saw a boom in uranium mining in the western U.S., spurred by the fortunes made by prospectors such as Charlie Steen. The United States was the world's leading producer of uranium from 1953 until 1980. In 1980 annual U.S. production peaked at 43.7 million pounds of U3O8.[2] Until the early 1980s, there were active uranium mines in Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Washington and Wyoming.[4]

Price declines in the late 1970s and early 1980s forced the closure of numerous mines. Most uranium ore in the United States comes from deposits in sandstone, which tend to be of lower grade than those of Australia and Canada. Because of the lower grade, many uranium deposits in the United States became uneconomic when the price of uranium declined sharply in the late 1970s. By 2001, there were only three operating uranium mines (all in-situ leaching operations) in the United States. Annual production reached a low of 779 metric tons of uranium oxide in 2003, but then more than doubled in three years to 1672 metric tons in 2006, from 10 mines.[5] The U.S. DOE's Energy Information Administration reported that 90% of U.S. uranium production in 2006 came from in-situ leaching.[6]

The average spot price of uranium oxide (U3O8) increased from $7.92 per pound in 2001 to $39.48 per pound ($87.04/kg) in 2006.[7] In 2011 the United States mined 9% of the uranium consumed by its nuclear power plants.[8] The remainder was imported, principally from Russia and Kazakhstan (38%), Canada, and Australia.[9][10][11] Although uranium production has declined to low levels, the United States has the fourth-largest uranium resource in the world, behind Australia, Canada, and Kazakhstan.[10] United States uranium reserves are strongly dependent on price. At $50 per pound U3O8, reserves are estimated to be 539 million pounds; however, at a price of $100 per pound, reserves are an estimated 1227 million pounds.[12] Rising uranium prices since 2001 have increased interest in uranium mining in Arizona, Colorado, Texas and Utah.[13][14] The states with the largest known uranium ore reserves (not counting byproduct uranium from phosphate) are (in order) Wyoming, New Mexico, and Colorado.[15]

The radiation hazards of uranium mining and milling were not appreciated in the early years, resulting in workers being exposed to high levels of radiation. Radon gas is a colorless, odorless, radioactive gas that forms naturally from the decay of radioactive elements like uranium, found in rocks and soil. Inhalation of radon gas caused sharp increases in lung cancers among underground uranium miners employed in the 1940s and 1950s.[16][17][18] In 1950, the US Public Health service began a comprehensive study of uranium miners, leading to the first publication of a statistical correlation between cancer and uranium mining, released in 1962.[19] In 1969, the federal government regulated the standard amount of radon in mines.[20] In 1990, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), granting compensation for those affected by mining.[19] Out of 50 present and former uranium milling sites in 12 states, 24 have been abandoned and are the responsibility of the US Department of Energy.[21]

By state

editAlabama

editUranium in Alabama is found in the Coosa Block of the Northern Alabama Piedmont. Metamorphic uranium occurrences have been found in the Higgins Ferry Group in Coosa and Clay Counties. Some exploration has been done, but no economic deposits have been found to date.

Alaska

editAlaska's only uranium mine, Ross-Adams, was discovered in 1955 by an airborne gamma radiation survey. The deposit is on the side of Bokan Mountain on Prince of Wales Island. The principal ore mineral is uranothorite, which occurs in veinlets in granite. Accessory minerals are primarily hematite and calcite, with lesser amounts of fluorite, pyrite, galena, quartz, and rare earth minerals. Mining commenced in 1957, when approximately 18,000 tonnes of thorium-bearing uranium ore grading 1% U3O8 was recovered from an open pit. Additional mining took place in 1961–1962 (6800 tonnes of ore), 1963 (10,880 tonnes), and 49,885 tonnes from 1968–1971 from underground operations.[22] A total of 1.3 million pounds of U3O8 at a grade of 0.76% was produced from open pit and underground operations, with milling taking place in Washington and Utah.[23]

Arizona

editUranium mining in Arizona has taken place since 1918. Prior to the uranium boom of the late 1940s, uranium in Arizona was a byproduct of vanadium mining of the mineral carnotite.[24]

California

editUranium was discovered in 1954 in the Sierra Nevada of Kern County, along the Kern River about 30 miles (50 km) northeast of Bakersfield. Two mines, the Kergon mine and the Miracle mine, made small shipments in 1954 and 1955. Uranium occurs as uraninite and autunite in shear zones in granodiorite. Accessory minerals include fluorite and the molybdenum minerals ilsemannite and jordisite.[25]

Colorado

editThe first uranium identified in the US was pitchblende from the Wood gold mine at Central City, Colorado in 1871. Uranium mining in southwest Colorado goes back to 1898. The Uravan district of Colorado and Utah supplied about half the world's radium from 1910 to 1922, and vanadium and uranium were byproducts. The last producing uranium mine in the state, the Topaz Mine, part of the Sunday Complex near Uravan, Colorado, was closed down on March 18, 2009, by then owner Denison Mines due to depressed uranium prices. On July 6, 2021 Western Uranium & Vanadium Corp announced the resumption of mining activities at the Sunday Mine Complex. On February 14, 2022 Western Uranium & Vanadium Corp announced 2,000 tons of new production was moved into four separate underground stockpiles. [26] [27][28]

Florida

editThe Central Florida (Bone Valley) phosphorite deposits are considered to contain the largest known uranium resource (one million metric tons of uranium oxide) in North America (but note that resources are not the same as ore reserves). Uranium has been produced as a byproduct of phosphate mining and the production of phosphoric acid fertilizer. The uranium is contained in the phosphate minerals francolite, crandallite, millisite, wavellite, and vivianite, found in Miocene and Pliocene sediments of the Bone Valley Formation. The average uranium content is 0.009%, which is considered to be low grade. Concentrations of uranium in this type of deposit typically grade to 0.01–0.015% U3O8.[29] Recovery process costs are estimated at $22 to $54 per pound of U3O8; higher than the market price of uranium during the 25-year period spanning the 1980s through the early first decade of the 21st century. Consequently, uranium recovery from Florida phosphate ceased in 1998.[30]

Idaho

editFrom 1955 to 1960, uranium was extracted from placer black sand deposits derived from the Idaho Batholith in southwest Idaho. The deposits were mined for uranium, thorium, and rare earths. Uranium and thorium were in the monazite grains; rare earths were in columbite and euxenite. Production was 365,000 pounds (165 metric tons) of U3O8.[31]

Uranium was mined at the Stanley district in Custer County, Idaho from 1957 to 1962. Deposits occur as veins in granite of the Cretaceous Idaho Batholith, and in strataform deposits in possibly Paleocene arkosic conglomerates and sandstones between the underlying Idaho Batholith and overlying Challis Volcanic Group (Eocene). The USGS has estimated production to be less than 170,000 pounds (78 metric tons) of U3O8.[32]

Nebraska

editThe only operating uranium mine in Nebraska is the Crow Butte mine, operated by Cameco. The mine is five miles (8.0 km) southeast of Crawford in Dawes County, western Nebraska.[33] The roll-front deposit in the Oligocene Chadron formation was discovered in 1980 by Wyoming Fuel Co.[34] Commercial operation began in 1991.[35] Uranium is mined by in-situ leaching which involves the extraction by boreholes of uranium-bearing (U3O8) water, which is then filtered through resin beads. Through an ion exchange process, the resin beads attract uranium from the solution. Uranium loaded resins are then transported to a processing plant, where U3O8 is separated from the resin beads and yellowcake is produced. The resin beads are returned to the ion exchange facility where they are reused.[36][37]

Nevada

editThere is no current uranium production from Nevada. The largest past-producer was the Apex mine (also called Rundberg or Early Day mine), three miles south of Austin, in Lander County. Discovered in September 1953, it was first mined as a silver deposit and produced 45 metric tons of U3O8 (80% of Nevada's historical production) from 1954 until 1966, from a small open pit and from underground. Ore was shipped to Utah and to Lakeview, Oregon for processing.[38][39] Uranium occurs as the secondary minerals autunite and meta-autunite after uraninite and coffinite in fractured Cambrian metamorphosed shales and quartzite, at or near the contact with Jurassic porphyritic quartz monzonite.[40][41][42] The Apex-Lowboy deposit has an inferred resource of 615,000 metric tons at a grade of 0.07% U3O8.[43]

The McDermitt Caldera in Humboldt County was the site of intensive uranium exploration in the late 1970s. In 2006 and 2007, Western Uranium Corporation drilled exploratory boreholes in the Kings Valley area.[44]

New Jersey

editA uranium exploration project in northern New Jersey was halted in 1980 when the local government passed an ordinance preventing uranium mining after protests in Jefferson Township.[45]

New Mexico

editNew Mexico was a significant uranium producer since the discovery of uranium by Navajo sheepherder Paddy Martinez in 1950. Uranium in New Mexico is almost all in the Grants mineral belt, along the south margin of the San Juan Basin in McKinley and Cibola counties, in the northwest part of the state.[46] No mining has been done since 2002, even though the state has second-largest known uranium ore reserves in the US.[47]

North Dakota

editSome lignite coal in southwest North Dakota contains economic quantities of uranium. From 1965 to 1967 Union Carbide operated a mill near Belfield in Stark County to burn uraniferous lignite and extract uranium from the ash. The plant produced about 150 metric tons of U3O8 before shutting down.[48]

Oklahoma

editA small amount of uranium ore was mined in the mid-1950s from a surface exposure at Cement in Caddo County. The uranium occurred as carnotite and tyuyamunite in fracture fillings in the Rush Springs Sandstone over the Cement anticline, where the sandstone is bleached.[49][50] The mined area was 150 feet (46 m) long, 3 to 5 feet (0.9 to 1.5 m) wide, and extended 3 to 5 feet (0.9 to 1.5 m) below ground surface.[51]

Oregon

editUranium was discovered in Oregon in 1955, 20 miles northwest of Lakeview in Lake County. The White King mine and the Lucky Lass mine shipped uranium from 1955 until 1965. At the White King mine, uranium was mined by both underground and open-pit methods from a low-temperature hydrothermal deposit in Pliocene volcanic rocks, associated with opal, realgar, stibnite, cinnabar, and pyrite. At the Lucky Lass mine ore was mined from an open pit. Uranium occurs in uraninite and autunite in lenses near or in a fault zone in tuffs. The mines fed the Lakeview Mining Company uranium mill.[52][53]

A minor amount of uranium was mined in 1960 from a deposit at Bear Creek Butte in Crook County. The uranium was present as autunite at the contact between a rhyolite dike and tuffs of the Oligocene-Miocene John Day Formation.[53]

The McDermitt Caldera in Malheur County was the site of intense uranium exploration in the late 1970s. Portland-based Oregon Energy is planning development of the Aurora deposit, near McDermitt. Mining and infrastructure studies are finalised, and metallurgical testwork is expected to conclude in 2024.[54][55]

Pennsylvania

editThe uranium mineral autunite was reported in 1874 near the town of Mauch Chunk (present-day Jim Thorpe) in Carbon County, eastern Pennsylvania.[56] A small amount of test mining was done in 1953 at the Mount Pisgah deposit near Jim Thorpe. The uranium at the Mount Pisgah deposit is primarily in an unidentified black mineral in pods and rolls in the basal conglomerate of the Mauch Chunk Formation (Mississippian). Also present are the secondary uranium and uranium-vanadium minerals carnotite, tyuyamunite, liebigite, uranophane, and betauranophane.[57]

Uranium has been located in only a small portion of the county near the Lehigh River valley and all of the deposits have been named. Mount Pisgah, Mauch Chunk Ridge, Butcher Hollow, and Penn Haven Junction are all within 6 miles of the town. First recognized in 1874, the land that these uranium deposits were found on was partially owned by Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company.[58] The land came to be owned by this company because the founders of the town, Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, were also founders of the company. Mauch Chunk was primarily a company town.

The test mining that was done in Carbon County has raised concerns because of higher chances of polluted water and release of radioactive material. With Jim Thorpe, PA being located right on the Lehigh River, any release of radioactive materials in that area could cause significant environmental damage there and further downstream in the Delaware River. The core drilling test mining occurred in 1953 at the Mauch Chunk Ridge deposit but has seen no further development due to the low uranium content in the rock of about .011 to .013%.[58]

South Dakota

editUranium was discovered near Edgemont, South Dakota in 1951, quickly followed by mining. The uranium occurs in Cretaceous sandstones of the Inyan Kara group, where it outcrops along the southern edge of the Black Hills in Fall River County, South Dakota. Minerals in unoxidized sandstone are uraninite and coffinite; minerals in oxidized zones include carnotite and tyuyamunite.[59]

An airborne gamma radiation survey flown by the US Atomic Energy Commission in 1954 discovered high radiation readings over the Cave Hills area in Harding County, in the northwest corner of the state.[60] High winds blew the reconnaissance flight off their planned survey route over the Slim Buttes twenty miles southeast of the North Cave Hills. Claims were immediately staked over uranium-bearing lignite beds in the area. The lignite was strip-mined, probably starting that same year, and continuing until the mines closed in 1964.[61]

No uranium is currently mined in South Dakota.[62]

In January 2007[63] Powertech Uranium Corporation received a state permit to drill boreholes to evaluate its Dewey-Burdock project, in Custer and Fall River counties northwest of Edgemont.[64] Previous work at the property in the early 1980s defined a resource of 10 million pounds (4500 metric tons) of uranium, of which 5 million pounds (2300 metric tons) were estimated recoverable by conventional underground mining.[65] By 2019 Powertech (now a subsidiary of enCore Energy Corp)[66] had increased the measured and indicated resource to 17.1 million pounds of uranium oxide and plans to bring the property into production as an in-situ leaching mine.[62][67][68]

A campaign has been underway to halt any effort to mine uranium in the Black Hills because of its effect on Native American and wildlife populations, as well as the effects of mining on the water table and local ranchers.[69][70] Indigenous leaders and anti-nuclear activists began organizing around this issue in the 1970s and there are still efforts underway to prevent mining on native lands.[71][72]

Texas

editThe uranium district of south Texas was discovered by accident in 1954 by an airborne gamma radiation survey looking for petroleum deposits. The coastal plain had previously been regarded as highly unfavorable for uranium deposits.[73] The uranium occurs in roll-front type deposits in sandstones of Eocene, Oligocene and Miocene age.[74] The deposits are distributed along about 200 miles (320 km) of coastal plain, from Panna Maria in the north, south into Mexico. Uranium production began in 1958, from open-pit and in situ leach mines.

Uranium production stopped in 1999, but restarted in 2004.[75] By 2006, three mines were active: Kingsville Dome in Kleberg County, the Vasquez mine in Duval County, and the Alta Mesa mine in Brooks County. 2007 production was 1.34 million pounds (607 metric tons) of U3O8. All have since closed.[76]

Uranium Energy Corp. (UEC) began in-situ leach mining at its Palangana deposit (grading .135% U3O8) in Duval County in 2010. Uranium loaded resins from that ion exchange facility are processed into yellowcake at the company's Hobson processing plant. In late 2012, UEC completed the permitting and approval process for the Goliad ISR mining and ion exchange facility in Goliad County.[77]

Utah

editMining of uranium-vanadium ore in southeast Utah goes back to the late 19th century. All of Utah's numerous uranium mines had closed by 1991 because of low prices. In late 2006, Denison Mines reopened the Pandora mine in the La Sal mining district, Utah's first producing uranium mine since 1991.[78] In 2009 White Canyon Uranium opened the Daneros underground mine, 40 miles (64 km) west of Blanding, trucking ore to Denison's White Mesa Mill. In 2011 Denison took over White Canyon Uranium.[79] In 2012 Energy Fuels Inc. acquired Denison's US assets, including the White Mesa Mill. In October 2012 the only operating uranium mines in Utah, the Pandora, Beaver and Daneros mines, were all placed on standby, care and maintenance due to the depressed uranium price.[80][81][82][83]

The White Mesa Mill, 7 miles (11 km) miles south of Blanding, Utah, is the only operating conventional uranium (and vanadium) mill in the United States.[83][84]

Virginia

editThe largest deposit of uranium in the US is in Virginia at Coles Hill; however, the state's generous rainfall and occasional flooding (in contrast with typical American uranium mines in the dry and isolated desert southwest) have led to citizen concern about commercial-scale mining.[85] Lawmakers in the state enacted a de facto ban on uranium mining in 1982. A 2015 federal court case involving the owners of Coles Hill upheld the ban.

Marline Uranium Corp. announced in July 1982 that it had discovered 110 million pounds (50,000 metric tons) of uranium in the Swanson/Coles Hill deposit, on land that it had leased near Chatham in Pittsylvania County. During the 1982 legislative session, the state of Virginia adopted laws to govern exploration for uranium in the Commonwealth. At the same time, the legislature imposed a moratorium on uranium mining in the state until such time that regulations to govern uranium mining could be enacted into law.[86]

In 1981, the Virginia General Assembly approved House Joint Resolution No. 324, which directed the Virginia Coal and Energy Commission to evaluate the effects of uranium development on the Commonwealth and its citizens. The Virginia Coal and Energy Commission is a permanent legislative commission composed of five Senators, eight Delegates, and seven citizens appointed by the Governor.

The Commission completed its evaluation of uranium mining in October 1984 and concluded that the moratorium regarding uranium development could be lifted on the condition that certain specific recommendations derived from its work would be enacted into law.

Union Carbide was the joint venture partner on the project with Marline until early 1984 when it dropped its option on the property due to declining uranium prices. Marline kept the project on care and maintenance until 1990, when it dropped its remaining mineral leases and closed its local exploration office.[87]

The deposits occur as breccia-fill and veins in gneiss bordering the Triassic Danville Basin.[88] Ore minerals are coffinite, uraninite, and uranium-bearing apatite.[89]

In October 2007, Walter Coles, who owns the land over the Coles Hill deposit, announced that he and some other landowners had formed Virginia Uranium Inc. to mine the deposit themselves, if it can be done safely.[90][91] In November 2007, the state issued an exploration permit to Virginia Uranium, to allow drilling test holes into the deposit. Drilling began in mid-December.

The state-imposed moratorium on uranium mining is still in effect. A bill proposed in the state General Assembly in January 2008 would have created a Virginia Uranium Mining Commission to determine if uranium mining could be done in a manner protective of human health and the environment, and to recommend regulatory controls.[92] The bill passed the Democratic controlled state Senate by a vote of 36–4. However, opponents of uranium mining succeeded in stopping the bill on March 3, 2008, when Rules Committee of the Republican controlled House of Delegates delayed consideration of the bill until 2009.[93]

In November 2008, the Virginia Coal and Energy Commission voted unanimously to once again create a subcommittee to study the issue of uranium mining.[94] In May 2009 the subcommittee approved a study of potential uranium mining and its safety and pollution issues. The study is expected to take about 18 months to complete.[95]

In February 2010, the Commonwealth of Virginia contracted the National Research Council and Virginia Polytechnic Institute to oversee a National Research Council study of potential environmental and economic effects of uranium mining in Virginia. The National Research Council study, funded indirectly by a $1.4 million grant from Virginia Uranium to the Commonwealth, resulted in a report released in December 2011.[96]

The report identified a range of health and environmental issues and related risks that could result from uranium mining in the Commonwealth of Virginia. The report found that although there are internationally accepted best practices to mitigate some risks, Virginia faces "steep hurdles" if it is to undertake uranium mining and processing within a regulatory setting that appropriately protects workers, the public, and the environment.[97]

Uranium mining and processing carries with it a range of potential health risks to the people who work in or live near uranium mining and processing facilities. Some of these health risks apply to any type of hard rock mining or other large-scale industrial activity, but others are linked to exposure to radioactive materials. In addition, uranium mining has the potential to impact water, soil, and air quality, with the degree of impact depending on site-specific conditions, how early a contaminant release is detected by monitoring systems, and the effectiveness of mitigation steps.[98]

Some of the worker and public health risks could be mitigated or better controlled through modern internationally accepted best practices, the report says. In addition, if uranium mining, processing, and reclamation were designed, constructed, operated, and monitored according to best practices, near-to-moderate-term environmental effects should be substantially reduced, the report found.[99]

However, the report noted that Virginia's high water table and heavy rainfall differed from other parts of the United States—typically dry, Western states—where uranium mining has taken place. Consequently, federal agencies have little experience developing and applying laws and regulations in locations with abundant rainfall and groundwater, such as Virginia. Because of Virginia's moratorium on uranium mining, it has not been necessary for the Commonwealth's agencies to develop a regulatory program that is applicable to uranium mining, processing, and reclamation.

The report also noted the long-term environmental risks of uranium tailings, the solid waste left after processing. Tailings disposal sites represent potential sources of contamination for thousands of years. While it is likely that tailings impoundment sites would be safe for at least 200 years if designed and built according to modern best practices, the long-term risks of radioactive contaminant release are unknown.

The report's authoring committee was not asked to recommend whether uranium mining should be permitted, or to consider the potential benefits to the state were uranium mining to be pursued. It also was not asked to compare the relative risks of uranium mining to the mining of other fuels such as coal.

In October 2015, it went before a federal judge whether the 33-year-old ban on large-scale uranium mining in Virginia would be lifted. [100] In June 2019, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that, in the absence of federal law establishing otherwise, "...[states retain] authority over the regulation of mining activities on private lands within their borders,”[101] and therefore the state ban on uranium mining remains in place.[102]

Washington

editUranium was discovered at the Midnite Mine deposit on the Spokane Indian Reservation, Stevens County, north-east Washington in 1954. The deposit was mined from an open pit 1956–1962 and 1969–1982.[103] Production through 1975 was 8 million pounds (3,600 metric tons) of U3O8. The uranium is contained in autunite, uraninite, and coffinite, with gangue minerals pyrite and marcasite. The ore occurs as disseminations, replacements, and stockworks in Precambrian metamorphic rocks of the Togo formation, in a roof pendant in Cretaceous porphyritic quartz monzonite.[104]

Western Nuclear discovered the Spokane Mountain uranium deposit in 1975, two miles (3.2 km) northeast of the Midnite Mine, and in a similar geologic setting.[105]

Other major Washington state uranium mines included the Sherwood mine, located five miles south of the Midnite mine, and the Daybreak mine, located six miles southeast of Elk, Washington. The Daybreak mine is recognized as the source of the finest museum-quality specimens of autunite and meta-autunite yet found. Sherwood had a co-located uranium mill, while Midnite and Daybreak ores were processed at the Dawn uranium mill, at Ford, Washington.[106]

Wyoming

editWyoming once had many operating uranium mines, and once had the largest known uranium ore reserves of any state in the U.S. The Wyoming uranium mining industry was hard-hit in the 1980s by the drop in the price of uranium. The uranium-mining boom town of Jeffrey City lost 95% of its population in three years. By 2020, the only active uranium mine in Wyoming was the Smith Ranch-Highland in-situ leaching operation in the Powder River Basin, owned by Cameco.[107] The mine has produced 23 million pounds of uranium since it opened in 1975. Wellfield development was suspended during 2016. The Measured and Indicated Resource is 24.9 million pounds of U3O8 at a grade of 0.06%.[108][109]

Health and environmental issues

editThe radiation hazards of uranium mining and milling were not appreciated in the early years, resulting in workers being exposed to high levels of radiation. Inhalation of radon gas caused sharp increases in lung cancers among underground uranium miners employed in the 1940s and 1950s.[16][17][18] Risks related to the inhalation of radon gas and the deposition of radon daughter products in the lung were discussed publicly as early as 1951 in American newspapers. The hazard was considered to be generally greater in deeper underground workings, where providing adequate ventilation and suppressing dust was more difficult. Concerns for American miners' health were based on the observation of elevated lung cancer incidence among miners who mine uranium-bearing ore underground in Czechoslovakia and Germany.[110]

Conventional uranium ore treatment mills create radioactive waste in the form of tailings, which contain uranium, radium, and polonium. Consequently, uranium mining results in "the unavoidable radioactive contamination of the environment by solid, liquid and gaseous wastes".[111]

In the 1940s and 1950s, uranium mill tailings were released with impunity into water sources, and the radium leached from these tailings contaminated thousands of miles of the Colorado River system. Between 1966 and 1971, thousands of homes and commercial buildings in the Colorado Plateau region were "found to contain anomalously high concentrations of radon, after being built on uranium tailings taken from piles under the authority of the Atomic Energy Commission".[112]

In 1950, the US Public Health service began a comprehensive study of uranium miners, leading to the first publication of a statistical correlation between cancer and uranium mining, released in 1962.[19] The federal government eventually regulated the standard amount of radon in mines, setting the level at 0.3 WL on January 1, 1969.[20]

Out of 50 present and former uranium milling sites in 12 states, 24 have been abandoned, and are the responsibility of the US Department of Energy.[113] Accidental releases from uranium mills include the 1979 Church Rock uranium mill spill in New Mexico, called the largest accident of nuclear-related waste in US history, and the 1986 Sequoyah Corporation Fuels Release in Oklahoma.[114]

In 1990, Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), granting reparations for those affected by mining, with amendments passed in 2000 to address criticisms with the original act.[19]

The Navajo people have had a long history of dealing with the physical effects and environmental burden from uranium mining on their lands. This not only includes those who have worked in the mines but those who have never stepped foot in one and have to deal with the radioactivity in the surrounding areas. This has led to higher developments of different types of cancer and respiratory and kidney conditions. While the Lukachukai Mountain site was still functioning, there were slow and fast forms of radiation exposure. Because uranium and its health concerns were unknown to the Navajo people at the time, workers would come home covered in dust from the mines that had traces of uranium and other radioactive materials. This would cause more sudden forms of radiation exposure, but the contamination of land and water sources would happen slowly over time and leech into Navajo households. Reporter Noel Lyn Smith has earned her master’s degree in investigative journalism and is focusing on all aspects of the Navajo Nation with specific interest in the government, who has gotten involved and declared the Lukachukai Mountains Mining District a superfund site which means that a door has been opened for federal funding to help clean up the “more than 800,000 cubic yards of mine waste in piles scattered throughout the site.”[115]

Uranium mining, milling and the American Southwest

editIn the post-war period mine workers in the Four Corners area were exposed to and brought home large amounts of radiation in the form of dust on their clothing and skin. Epidemiologic studies of the families of these workers have shown increased incidents of radiation-induced cancers, miscarriages, cleft palates and other birth defects.[116][117][118] The extent of these genetic effects on indigenous populations and the extent of DNA damage remains to be resolved.[119][120][121][122][123][124]

All over the American Southwest, Uranium mines are seeing a revival. There are multiple plans to reopen closed mines in Texas, Utah, Wyoming, and Arizona. While all of this is happening, this country is still dealing with the same environmental injustices that these mining practices have caused. After the Fukushima disaster, many uranium mines closed because uranium prices dropped so much it wasn’t an economically good choice to keep mining. Now, after last year's United Nations Climate Conference in Dubai, climate change and spiking uranium prices has put a spark back in the idea of nuclear power.[125] This is a big positive for those who are rooting for a nuclear future, but others have concerns about the environmental damages that this could cause in the future along with the environmental injustices that have already taken place in indigenous communities.

Native tribes have already started a push to shut down new mining operation plans and are highlighting the need for approval of those in the community unlike previous instances where the current system of colonialism has been the primary way of thinking. One of these previous instances has been the Church Rock Mine in New Mexico, owned by United Nuclear Corporation. The dam that was holding 94 million gallons of radioactive waste broke, made its way onto Navajo lands, and now contaminates the land that their animals graze on to this day.[125]

Some believe that as America heads towards a green energy future, the increase in critical mineral extraction cannot lead towards a future of green colonialism. The thought being that Tribal Nations must have a more meaningful stake in the future of critical mineral mining if the United States wants to decrease dependency on foreign nations for critical minerals. It is also thought that the Government must develop a policy that ensures we don’t repeat history. Colonialism won’t cut it anymore. Mark Trahant, a former editor for Indian Country Today, says “This time it’s different, perhaps, because tribal nations can either be essential producers or legal obstacles and irritants.”[126]

Uranium mining, milling and the Navajo people

editAfter the end of World War II, large uranium deposits were found on and near the Navajo Reservation in the Southwest, and private companies hired many Navajo employees to work the mines. Disregarding the known health risks imposed by exposure to uranium, the private companies and the United States Atomic Energy Commission failed to inform the Navajo workers about the dangers and to regulate the mining to minimize contamination. As more data was collected, they were slow to take appropriate action for the workers.[19]

Studies provided data to show that the Navajo mine workers and numerous families on the reservation have suffered high rates of disease from environmental contamination, but for decades, industry and the government failed to regulate or improve conditions, or inform workers of the dangers. As high rates of illness began to occur, workers were often unsuccessful in court cases seeking compensation, and the states at first did not officially recognize radon illness.[19]

Lands that have been subject to permanent environmental damages for the collective good are referred to as “national sacrifice zones.” These zones have been commonly caused by polluting industries such as uranium mining sites and United States Military bases. Polluting industries like these leave hazardous chemicals in their wake for the surrounding residents and threaten the economics, cultures and welfare of the tribes living in or near these sacrifice zones.[127] Environmental Justice Scholar Kyle Keeler states that sacrifice zones are “for the betterment of colonial society”[128] Throughout the 20th century, the Navajo nation has been subject to these sacrifice zones due to exploitation from the country’s nuclear goals. As Scholar Traci Brynne Voyles has mentioned in her book, “Diné land hosts upward of 2,000 now-abandoned uranium mines, mills, and tailings piles, in which over 3,000 Navajo miners wrenched and blasted raw uranium ore from the ground and then processed it into yellowcake.”[129]

“Wastelanding” is a term that was coined by Traci Brynne Voyles in her book, and she describes it as a place “from which resources are increasingly extracted and where (often toxic) waste is increasingly dumped.”[129] It is used to describe the environmental and social impacts of uranium mining. The people that live on these wastelands are subject to disproportionate amounts of exposure to environmental harms, like groundwater contamination and the effects from PCBs being in their system. The Manhattan project is one of the main reasons the Navajo reservation has so many abandoned mines on it today. Being located in Los Alamos, the United States government was in very close proximity to the uranium mines found on Navajo lands. They took advantage of this and started the rush towards a nuclear weapons future. Princeton University’s Nuclear Program has released an article that talks about how “Tribal nations were displaced from their homelands for the construction of these facilities and were often denied access to their homelands both throughout the project and to the present day.”[130]

In 1990 the US Congress passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, to settle such cases and provide needed compensation.[131][19] In 2008 the US Congress authorized a five-year, multi-agency cleanup of uranium contamination on the Navajo Nation reservation; identification and treatment of contaminated water and structures has been the first priority. Certain water sources have been closed, and numerous contaminated buildings have been taken down.[132] By the summer of 2011, EPA had nearly completed the first major project of removal of 20,000 cubic yards of contaminated earth from the Skyline Mine area.

Uranium mining has disturbed the balance in Navajo culture. They must stay and fight for their land but are dealing with so many adverse health and environmental effects because of it.[133] The Holy People in Navajo culture have set the boundaries of their land, and the earth people must do whatever they can to try to heal and protect that land.[134] Trying to seek justice for the effects of uranium mining have been continuous, with groups like Eastern Navajo Diné Against Uranium Mining playing a critical role. ENDAUM was created in 1994 to combat plans to open uranium mines that were presented by HydroResources Inc.[135] They have been fighting the same overall cause for three decades now. Workers had not been informed of the dangers uranium mining would inflict on their land.[136] This is only a little part of a much larger issue, with economic issues being a top priority in our country and shutting out the rights and well-being of indigenous people.

See also

edit- Anti-nuclear movement in the United States

- Botanical prospecting for uranium

- List of uranium projects

- Nuclear labor issues

- Nuclear power in the United States

- The Return of Navajo Boy, a 2000 documentary film about Navajo struggling with the legacy of uranium mining on their lands

- Uranium Mill Tailings Radiation Control Act

- Virginia Uranium, Inc. v. Warren

References

edit- ^ "Domestic Uranium Production Report - First-Quarter 2020" (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration. 3 May 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ a b c "Table 8.2 Uranium Overview" (PDF). Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration. April 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ "Domestic Uranium Production Report - Quarterly". Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration. 20 February 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Finch, Warren I.; Butler, Arthur P.; Armstrong, Frank C.; Weissenborn, Albert E.; Mortimer, H. Staatz (1973). "Nuclear fuels" (PDF). United States Mineral Resources. Geological Survey Professional paper 820. U.S. Department of the Interior: 457. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- ^ "World Uranium Mining 2011". World-nuclear.org. Archived from the original on 2009-06-18. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ U.S. Energy Information Administration: U.S. uranium mine production and number of mines and sources, accessed 6 March 2009.

- ^ Department of Energy's Energy Information Administration data, official energy statistics from the U.S. Government

- ^ US Energy Information Administration, Where our uranium comes from, 2 July 2012.

- ^ "Over 90% of uranium purchased by U.S. commercial nuclear reactors is from outside the U.S." Today in Energy. Washington, DC: U.S. Energy Information Administration. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ a b Warren I Finch (2003) Uranium-fuel for nuclear energy 2002, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 2179-A.

- ^ See S&TR: September 2005, How One Equation Changed the World, which discusses the progress of the HEU Purchase Agreement made between the Russian Federation and the United States in 1993. "Currently, Russian plants are processing about 30 metric tons of HEU per year into about 875 metric tons of LEU. This amount meets half the annual fuel requirement for U.S. nuclear power plants and provides the fuel to generate 10 percent of the electricity used in the U.S."

- ^ US Energy Information Administration, U.S. uranium reserves estimates, July 2010.

- ^ WISE Uranium Project: New uranium mining projects – USA, accessed 25 March 2009.

- ^ Moran, Susan; Raup, Anne (28 March 2007). "Uranium Ignites 'Gold Rush' in the West". The New York Times.

- ^ J. Keller and others, Colorado, Mining Engineering, May 2006, p. 76.

- ^ a b Roscoe, R. J.; K. Steenland; W. E. Halperin; J. J. Beaumont; R. J. Waxweiler (1989-08-04). "Lung cancer mortality among nonsmoking uranium miners exposed to radon daughters". JAMA. 262 (5): 629–633. doi:10.1001/jama.1989.03430050045024. PMID 2746814.

- ^ a b Roscoe, R. J.; J. A. Deddens; A. Salvan; T. M. Schnorr (1995). "Mortality among Navajo uranium miners". American Journal of Public Health. 85 (4): 535–540. doi:10.2105/AJPH.85.4.535. PMC 1615135. PMID 7702118.

- ^ a b "Uranium Miners' Cancer". Time Magazine. 1960-12-26. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on January 15, 2009. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dawson, Susan E, and Gary E Madsen. "Uranium Mine Workers, Atomic Downwinders, and the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act." In Half Lives & Half-Truths: Confronting the Radioactive Legacies of the Cold War, 117–143. Santa Fe: School For Advanced Research, 2007)

- ^ a b Brugge, Doug, Timothy Benally, and Esther Yazzie-Lewis. The Navajo People and Uranium Mining. Albuquerque : University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

- ^ "Nuclear Decommissioning Title 1 Uranium Mills Summary Table". Archived from the original on 2010-12-16. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ^ E.M. MacKevett Jr. (1963) Geology and Ore Deposits of the Bokan Mountain Uranium-Thorium Area, Southeastern Alaska, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1154.

- ^ "Project Highlights". Vancouver, BC: Ucore Uranium. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Allison, Lee (2 July 2012). "Development of northern Arizona uranium mine planned by year-end". Arizona Geology.

- ^ E.M. MacKevett Jr. (1960) Geology and Ore Deposits of the Kern River Uranium Area, California, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1087-F.

- ^ "News | Western Uranium & Vanadium Corporation". www.western-uranium.com. Retrieved 2022-03-09.

- ^ J. Burnell and others, Colorado, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p. 77.

- ^ Energy Fuels. "Sunday Complex". Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Warren I. Finch (1996) Uranium provinces of North America-their definition, distribution, and models, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 2141.

- ^ Energy Information Administration (12 Feb. 2008): 4th Quarter 2007 uranium production was 1.2 million pounds

- ^ Energy Information Administration: Lowman mill and disposal site

- ^ Bradley S. Van Gosen and others (2005) A Reconnaissance Geochemical and Mineralogical Study of the Stanley Uranium District, Custer County, Central Idaho, US Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations Report 2005-5264.

- ^ R.M. Lyman, Wyoming, Mining Engineering, May 2005 p. 130.

- ^ "Wma-minelife.com". www.wma-minelife.com.

- ^ Bergin, Nicholas (14 January 2016). "Company looking to expand depleted Panhandle uranium mine". Lincoln Journal Star. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Mining – Crow Butte – Extraction Process". Cameco. 2010-04-23. Archived from the original on 2012-05-12. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ Nuclear Regulatory Commission (13 Feb. 1998): Crow Butte resources Inc., Final finding of no significant impact

- ^ Castor, Stephen B.; Ferdock, Gregory C. (2004). Minerals of Nevada. Reno, NV: Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology. p. 30. ISBN 9780874175400. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Mason, Ralph S. (January 1960). "Oregon's mineral industry in 1959" (PDF). The Ore.-Bin. 22 (1). Portland, OR: 7. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Plut, Frederick W. (1979). Newman, Gary W.; Goode, Harry D. (eds.). "Geology of the Apex Uranium Mine near Austin, Nevada". Basin and Range Symposium and Great Basin Field Conference. Denver CO: Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists: 413–420. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Garside, Larry J. (1973). Bulletin 81: Radioactive Mineral Occurrences in Nevada. Reno, NV: Nevada Bureau of Mines & Geology. p. 62. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ Nye, Thomas Spencer (1958). Geology of the Apex Uranium Mine, Lander County, Nevada. Berkeley, CA: University of California. p. 29.

- ^ Mineral Assessment Report – BMDO Planning Area (PDF). Battle Mountain, NV: Bureau of Land Management. January 2012. pp. 3–17. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "Kings Valley, Nevada, USA". Vancouver, Canada: Western Uranium Corporation. 2010. Archived from the original on 2010-03-30. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ Time (13 Oct. 1980):"In New Jersey: a uranium boom goes bust", accessed 25 March 2009.

- ^ Douglas G. Brookins (1977) Uranium deposits of the Grants mineral belt: geochemical constraints on origin, in Exploration Frontiers of the Central and Southern Rockies, Denver: Rocky Mountain Association of Geologists, pp. 337–352.

- ^ Gospodarczyk, Marta M. (July 2010). "U.S. Uranium Reserves Estimates" (PDF). Energy Information Administration, Department of Energy. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^

- US Energy Information Administration, Belfield Ashing facility site, accessed 25 March 2009.

- North Dakota Geological Survey: Uranium Archived 2007-06-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Becker, M.F.; Runkle, D.L. (1998). "Hydrogeology, water quality, and geochemistry of the Rush Springs aquifer, western Oklahoma". U.S. Geological Survey, Water Resources Division. doi:10.3133/wri984081. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Roy F. Allen and Richard G. Thomas, The uranium potential of diagenetically altered sandstones of the Permian Rush Springs Formation, Cement district, southwest Oklahoma, Economic Geology, Mar.–Apr. 1984, pp. 284–296.

- ^ Uranium in the Southern United States (1969) US Atomic Energy Commission, WASH1128, p. 52.

- ^ Peterson, Norman V. (February 1959). "Preliminary geology of the Lakeview uranium area, Oregon" (PDF). The Ore.-Bin. 21 (2): 11–16. Retrieved 18 Oct 2013.

- ^ a b Petersen, Norman V. (1969). "Uranium". Mineral and Water Resources of Oregon. Vol. Bulletin 64. Portland, OR: Department of Geology and Mineral Industries. pp. 180–184.

- ^ Cockle, Richard (January 8, 2012). "Malheur County targeted for gold, uranium mines". The Oregonian. Retrieved 18 Oct 2013.

- ^ "Scoping Study Interim Report" (PDF). Aurora Energy Metals. 25 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Harry Klemic and R.C. Baker (1954) Occurrences of Uranium in Carbon County, Pennsylvania, U.S. Geological Survey, Circular 350.

- ^ Harry Klemic, James C. Warren, and Alfred R. Taylor (1963) Geology and Uranium Occurrences of the Northern Half of the Leighton Pennsylvania Quadrangle and Adjoining Areas, US Geological Survey, Bulletin 1138.

- ^ a b Klemic, Harry; Baker, R.C. "Occurrences of Uranium in Carbon County, Pennsylvania" (PDF). Retrieved May 2, 2024.

- ^ Hart, Olin M. (1968). "Uranium in the Black Hills". Ore Deposits in the United States, 1933–1967. New York: American Institute of Mining Engineers. pp. 832–837.

- ^ Curtiss, Robert E. (June 1955). "A preliminary report on the uranium in South Dakota" (PDF). South Dakota Geological Survey. Vermillion, SD: University of South Dakota. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ [dead link] http://www.deq.state.mt.us/abandonedmines/NAAMLP/AML/NAAMLP%20Papers/2006%2028th%20Annual%20NAAMLP%20Papers/Paper%205%20--%20Stone-South%20Dakota.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Peplowski, Shelby (29 January 2024). "House Bill 1071 starts groundwork to bring Uranium mining and nuclear power to South Dakota". KEVN. Rapid City, SD. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Powertech Uranium Corporation". Archived from the original on 2007-07-23. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ [dead link]RSJ, 2007 Archived 2012-09-07 at archive.today RSJ, 2007

- ^ "PTech, 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ^ "enCore Energy and Azarga Uranium To Combine To Create Leading American Uranium ISR Company". PR Newswire. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "Dewey-Burdock Uranium Project Technical Report". Corpus Christi TX: enCore Energy Corp. 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "StockInterview.com". Archived from the original on 2007-08-10. Retrieved 2007-07-26.

- ^ Jones, Peter M. "Uranium mining in the Black Hills of South Dakota." July 19, 2007. Indigenous People's Issues Today

- ^ [dead link]White Face, Charmaine. "Black Hills – Powertech Exploratory Drilling." Archived 2009-02-08 at the Wayback Machine Aligning for Responsible Mining

- ^ White Face, Charmaine. "Stop Black Hills Uranium Mining." January 12, 2009. Republic of Lakotah website:

- ^ [dead link]South Dakota Department of Environment & Natural Resources: In Situ Leach Mine Regulations Archived 2008-03-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Southern Interstate Nuclear Board (1969) Uranium in the Southern United States, United States Atomic Energy Commission, p. 97.

- ^ William E. Galloway (2007) Geology of Texas uranium, in Geology of the Karnes Uranium District, Texas, Austin Geological Society Field Guidebook, pp. 9–19.

- ^ S.J. Clift and J.R. Kyle, Texas, Mining Engineering, May 2006, p. 114.

- ^ S.J. Clift and J.R. Kyle, "Texas," Mining Engineering, May 2008, p. 121.

- ^ * "Uranium production begins," Mining Engineering, December 2010.

- ^ Bon, Roger L.; Krahule, Ken (2010). "Uranium". 2009 Summary of Mineral Activity in Utah (Circular 111 ed.). Salt Lake City: Utah Geological Survey. p. 13.

- ^ Peters, Douglas C. (2 March 2018). "Updated Report On The Daneros Mine Project, San Juan County, Utah, U.S.A." (PDF). Denver, CO: Energy Fuels Inc. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Energy Fuels Inc., 2012 Annual Information Form" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2013-01-28.

- ^ "Energy Fuels to Focus on Lower Cost Uranium Production". Reuters. 17 October 2012. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Pistilli, Melissa. "Uranium Outlook 2013: Rebound on the Horizon". Uranium Investing News.

- ^ a b Associated, Press. "Energy Fuels to buy Utah's White Mesa uranium mill". The Denver Post.

- ^ "US Uranium Mining and Exploration". London: World Nuclear Association. October 2016. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Ward, Terry. "Uranium Mining Might Start in Virginia Soon". WHSV.com. Gray Digital Media. Archived from the original on 2016-01-20. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Problem while searching in Ecology and Natural Resources". Digicoll.library.wisc.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ IAEA Conference, June 2009, Uranium potential and socio-political environment for uranium mining in the Eastern United States with emphasis on the Coles Hill uranium deposit, IAEA-CN-175/91, PDF file, downloaded 24 July 2009.

- ^ "Geology, Mineralogy and Geochemistry of the Coles Hill Uranium Deposit, Virginia: An Example of a Structurally Controlled, Hydrothermal Apatite-Coffinite-Uraninite Orebody". Archived from the original on 2008-01-29. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ http://www.wpcva.com/articles/2007/11/28/chatham/news/news30.txt[permanent dead link]

- ^ http://www.wpcva.com/articles/2008/01/16/chatham/news/news31.txt[permanent dead link]

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ Virginia Commission on Coal and Energy (6 November 2008): Meeting summary Archived 15 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, PDF file, retrieved 5 March 2009.

- ^ Rex Springston, Richmond Times-Dispatch (22 May 2009): Va. uranium mining study approved Archived 2012-09-12 at archive.today, accessed 29 May 2009.

- ^ National Research Council, http://dels.nas.edu/Report/Uranium-Mining-Virginia-Scientific-Technical/13266

- ^ Non-Technical Summary, http://dels.nas.edu/Report/Uranium-Mining-Virginia-Scientific-Technical/13266

- ^ "Division on Earth and Life Studies". Dels.nas.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ "Newsroom". National-Academies.org. 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ^ * WHSV-TV (10 Oct. 2015) Uranium Mining Might Start in Virginia Soon Archived 2016-01-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Time (23 February 2009): In Virginia, the appeal of uranium mining

- Virginia Uranium Inc. website

- Virginia Department of Mines, Minerals, and Energy: Uranium Exploration Permit Approved Archived 2008-02-11 at the Wayback Machine

- MinDat.Org: Location maps – Swanson uranium project (Cole property), Pittsylvania Co., Virginia, retrieved 6 January 2009.

- Non-technical summary of the National Research Council report Uranium Mining in Virginia, retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ Marimow, Ann; Barnes, Robert (2019-06-17). "Supreme Court upholds Virginia's decades-old ban on uranium mining". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2019-06-17. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

"Congress conspicuously chose to leave untouched the States' historic authority over the regulation of mining activities on private lands within their borders," wrote Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, who was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett M. Kavanaugh. ...In her concurring opinion, Ginsburg rejected the company's warning of dire consequences if all 50 states enact such a ban. The federal government, she wrote, can still develop uranium on public land and acquire private deposits.

- ^ Mirengoff, Paul (17 June 2019). "Conservative Justices divide in case upholding Virginia's ban on uranium mining". Power Line.

- ^ S.S. Sumioka (1991) Quality of Water in an Inactive Uranium Mine and its Effects on the Quality of Water in Blue Creek, Stevens County, Washington, 1984–1985, US Geological Survey, Water-resources Investigations Report 89-4110.

- ^ J. Thomas Nash and Norman J. Lehman (1975) Geology of the Midnite Uranium Mine, Stevens County, Washington – a Preliminary Report, US Geological Survey, Open-File Report 75-402.

- ^ David A. Robbins, Applied geology in the discovery of the Spokane Mountain uranium deposit, Washington, Economic Geology, Dec. 1978, pp. 1523–1538.

- ^ Ream, Lanny R. (1991), "Two Autunite Localities in Northeastern Washington," Rocks & Minerals Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 294–297

- ^ "2019 Annual Report" (PDF). Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Cameco Corp. 7 February 2020. p. 72. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Smith Ranch-Highland". Saskatoon, Saskatchewan: Cameco Corp. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ W.M. Sutherland, Wyoming, Mining Engineering, May 2007, p. 126.

- ^ "Clipping from Greeley Daily Tribune on Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

- ^ Benjamin K. Sovacool (2011). Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, World Scientific, p. 137.

- ^ Benjamin K. Sovacool (2011). Contesting the Future of Nuclear Power: A Critical Global Assessment of Atomic Energy, World Scientific, p. 138.

- ^ "Decommissioning of U.S. Uranium Production Facilities" (PDF).

- ^ Doug Brugge, et al, "The Sequoyah Corporation Fuels Release and the Church Rock Spill", American Journal of Public Health, September 2007, Vol., 97, No. 9, pp. 1595–1600.

- ^ Smith, Noel (March 26, 2024). "This Month's Superfund Listing of Abandoned Uranium Mines in the Navajo Nation's Lukachukai Mountains Is a First Step Toward Cleaning Them Up". Inside Climate News.

- ^ Shields, L. M.; Wiese, W. H.; Skipper, B. J.; Charley, B.; Benally, L. (November 1992). "Navajo birth outcomes in the Shiprock uranium mining area". Health Physics. 63 (5): 542–51. doi:10.1097/00004032-199211000-00005. PMID 1399640.

- ^ Shuey, Chris. "URANIUM EXPOSURE AND PUBLIC HEALTH IN NEW MEXICO AND THE NAVAJO NATION: A LITERATURE SUMMARY" (PDF). Southwest Research and Information Center. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Dawson, Susan (December 1992). "Navajo Uranium Workers and the Effects of Occupational Illnesses: A Case Study" (PDF). Human Organization. 51 (4): 389–397. doi:10.17730/humo.51.4.e02484g513501t35. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Frosh, Dan (July 26, 2009). "Uranium Contamination Haunts Navajo Country". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Johnston, Barbara Rose; Holly M. Barker; Marie I. Boutte; Susan Dawson; Paula Garb; Hugh Gusterson; Joshua Levin; Edward Liebow; Gary E. Madsen; David H. Price; Kathleen Purvis-Roberts; Theresa Satterfield; Edith Turner; Cynthia Werner (2007). Half Lives & Half Truths: Confronting the Radioactive Legacies of the Cold War. Santa Fe, NM: School for Advanced Research Press. ISBN 978-1930618824.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brugge, Doug; Timothy Benally, Esther Yazzie-Lewis (2007). The Navajo People and Uranium Mining. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0826337795.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brugge, Doug; Timothy Benally, Ester Yazzie Lewis (9 April 2010). "Uranium Mining on Navajo Indian Land". Partnering with Indigenous Peoples to Defend their Lands, Languages and Cultures. Cultural Survival.org. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jung, Carrie. "Navajo Nation Opposes Uranium Mine on Sacred Site in New Mexico". Al Jazerra. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ Laramee, Eve Andree. "Tracking Our Nuclear Legacy: Now we are all sons of bitches". 2012. WEAD: Women Environmental Artist Directory. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ a b "A Nuclear Power Revival Is Sparking a Surge in Uranium Mining". Yale E360. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Trahant, Mark (2023-06-21). "This time it's different? The rush to mine Indigenous lands". ICT News. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Hooks, Gregory; Smith, Chad L. (2004). "The Treadmill of Destruction: National Sacrifice Areas and Native Americans". American Sociological Review. 69 (4): 558–575. doi:10.1177/000312240406900405. ISSN 0003-1224. JSTOR 3593065.

- ^ Keeler, Kyle (2024). "Nuclear Injustice: Why a Nuclear Renaissance is the Same Old Colonial Story". Cleveland Review of Books. 2 (1): 176.

- ^ a b Voyles, Traci Brynne (2015). Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-9267-5. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctt155jmrg.

- ^ "Impacts on Indigenous Communities". Nuclear Princeton. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ U.S. Government Printing Office, Senate Hearing 108-883. "An Overview of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Program". www.gpo.gov. United States Senate and the U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Navajo Nation: Cleaning Up Abandoned Uranium Mines, Federal Plans to Address Impacts of Uranium Contamination". U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ Fettus, Geoffry; Mckinzie, Matthew (March 2012). "Nuclear Fuel's Dirty Beginnings" (PDF).

- ^ "Navajo Cultural History and Legends". web.archive.org. 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2024-05-02.

- ^ Morgan, Leona (October 27, 2011). "ENDAUM Statement to the NM Indian Affairs Committee" (PDF).

- ^ Dawson, Susan; Madsen, Gary (2007). In Half Lives & Half-Truths: Confronting the Radioactive Legacies of the Cold War. Santa Fe: School For Advanced Research. pp. 117–143.

External links

edit- Uranium Mining from the Handbook of Texas Online

- The Return of Navajo Boy Webisodes, EPA Clean-up of uranium contamination at Navajo Reservation

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Energy.