| Mission insignia | |

|---|---|

Mir insignia | |

| Mission statistics | |

| Mission name | Mir |

| Call sign | Mir |

| Launch | February 19, 1986 21:28:23 UTC Baikonur, USSR |

| Re-entry | March 23, 2001 05:50:00 UTC |

| Crew | 28 long duration crews |

| Occupied | 4,594 days |

| In orbit | 5,511 days |

| Number of Orbits |

89,067 |

| Apogee | 393 km /244 mi |

| Perigee | 385 km /239 mi |

| Period | 89.1 min |

| Inclination | 51.6 deg |

| Distance traveled |

3,638,470,307 km / 2,260,840,632 mi |

| Orbital mass w/Spektr, Kristal, etc. |

124,340 kg |

| Configuration | |

| |

| Mir space station | |

Mir (Russian: Мир; lit. world and/or peace) was a Soviet (and later Russian) orbital station. It was humanity's first consistently inhabited long-term research station in space. Mir currently holds the record for longest continuous human presence in space at eight days short of 10 years. Through a number of collaborations, it was made internationally accessible to cosmonauts and astronauts of many different countries. Mir was assembled in orbit by successively connecting several modules, each launched separately from February 19, 1986 to 1996.

The station existed until March 23, 2001, at which point it was deliberately de-orbited, and broke apart during atmospheric re-entry.

The manufacturer of Mir was the Khrunichev State Space Scientific Production Center.

History

editMir was based upon the Salyut series of space stations previously launched by the Soviet Union (seven Salyut space stations had been launched since 1971). It was mainly serviced by Russian-manned Soyuz spacecraft and Progress cargo ships, but it was anticipated that it would also be the destination for flights by the later-abandoned Buran space shuttle. The orbiting Mir's purpose was to provide a large and habitable scientific laboratory in space.

The United States had planned to build Space Station Freedom as its counterpart to Mir, but this project was cancelled after the fall of the Soviet Union made an international cooperation possible (see International Space Station). Also, the space shuttle Challenger exploded less than a month before Mir was launched into orbit (see Space Shuttle Challenger disaster). In later years, after the end of the Cold War, the Shuttle-Mir program combined Russia's Mir capabilities with United States space shuttles and allowed American and other western astronauts to visit or stay long-term on the station. The visiting US shuttles used a modified docking collar originally designed for the Soviet Buran shuttle, mounted on a bracket originally designed for use with Space Station Freedom. With the space shuttle docked to Mir the temporary enlargements of living and working areas amounted to a complex that was the world's largest spacecraft at that time in space history, with a combined mass of 250 tons.

Inside, the 100-ton Mir looked like a cramped labyrinth, crowded with hoses, cables and scientific instruments – as well as articles of everyday life, such as photos, children's drawings, books and a guitar. It commonly housed three crewmembers, but it sometimes supported as many as six for up to a month. Except for two short periods, Mir was continuously occupied until August 1999.

In addition to Soviet/Russian cosmonauts, Mir hosted international scientists and U.S. astronauts.

International cooperation

editIn September 1993 U.S. Vice-President Al Gore and Russian prime minister Viktor Chernomyrdin announced plans for a new space station, which would later be called the International Space Station, or ISS. They also agreed that, in preparation for this new project, the U.S. would be involved in the Mir project in the years ahead, under the code name Phase One (the ISS being Phase Two). Space shuttles would take part in the transportation of supplies and people to and from Mir. U.S. astronauts would live on Mir for many months on end, allowing the U.S. to share and learn from the unique experience that Russia had with long duration space trips.

Starting from March 1995, seven U.S. astronauts consecutively spent 28 months on Mir. During their stay several acute emergencies occurred, notably a large fire on February 23 1997, and a collision with an unmanned Progress spacecraft on June 25 1997. On both occasions complete evacuation was avoided by a narrow margin (there was a Soyuz escape craft for return to earth). The second disaster left a hole in the Spektr module, which was then sealed off from the rest of the station. Several space walks were needed to restore full power to Mir (one of the "space walks" was inside the Spektr module from which all the air had escaped).

The cooperation between the U.S. and Russia proved far from easy. Distrust, lack of coordination, language problems, different views of each others' responsibilities and divergent interests caused many problems. After the emergencies, the U.S. Congress and NASA considered whether the U.S. should abandon the program out of concern for astronauts' safety. NASA administrator Daniel S. Goldin decided to continue the program. In June 1998, the final U.S. Mir astronaut Andy Thomas left the station aboard the Space Shuttle Discovery.

The story of Phase One is described in great detail by Bryan Burrough in his book Dragonfly: NASA and the Crisis Aboard Mir (1998).

The Mir space station was originally planned to be followed by a Mir 2, and elements of that project, including the core module (now called ISS Zvezda) which was labeled as "Mir-2" for quite some time in the factory, are now an integral part of the International Space Station.

Final Days and Deorbit

editNear the end of its life, there were plans for private interests to purchase Mir, possibly for use as the first orbital television/movie studio. A privately funded Soyuz mission carried two crew members to the station to carry out some repair work with the hope of proving that the station could be made safe; however this was to be the last manned mission to Mir. While Russia was optimistic about the future of Mir, commitments to the International Space Station project meant that there was no funding to support the aging station. Early proposals by Russia to use Mir as the core of the ISS were firmly rejected by NASA, and when the first ISS components were launched NASA insisted upon an orbit which effectively prevented transfer between the two stations. Many in the space community still felt that at least some of Mir was salvageable and that considering the extremely high costs of getting material into orbit, disposing of Mir was a wasted opportunity.

Mir's deorbit was conducted in three stages. The first stage was waiting atmospheric drag to decay Mir’s orbit an average of 220 km. This began with the docking of Progress M1-5, a modified version of the Progress M carrying 2.5 times more fuel in place of supplies. The second stage of the deorbit was the transfer of the station into a 165 x 220km orbit. This was achieved with two burns of the Progress M1-5's control engines at 00:32 UTC and 02:01 UTC on March 23, 2001. After a two orbit pause, the third and final stage of Mir's deorbit began with the a burn of Progress M1-5's control engines and main engine at 05:08 UTC lasting a little over 22 minutes. Reentry into the Earth's atmosphere (100km) of the 15-year-old Russian space station occured at 05:44 UTC near Nadi, Fiji. Major destruction of the station began around 05:52 UTC and the unburned fragments fell into the South Pacific Ocean around 06:00 UTC. [1][2]

Support craft

editThe Mir space station was primarily supported by the Russian Soyuz and Progress spacecraft. The Soyuz craft provided manned access to and from the station allowing for crew rotations. The Soyuz also fuctioned as a life boat for the station, allowing for a relatively quick return to earth in the event of an emergency. The unmanned progress cargo vehicles on the other hand were only used to resupply the station and were incapable of surviving reentry.

During the Shuttle-Mir Program, Mir was also supported by the Space Shuttle. The shuttle provided crew rotation of the US astronauts on station as well as carrying cargo to and from the station. The shuttle used some of the same systems originally developed for the Russian version of the space shuttle, the Buran Shuttle, which was also meant to support the station.

Soyuz (Союз) means "union", so named for the USSR (Sovietskii Soyuz, Советский Союз = Soviet Union) and because the spacecraft was a union of three smaller modules.

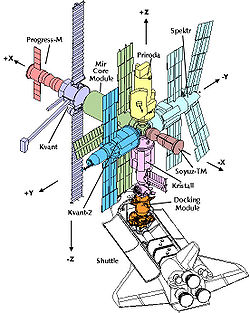

Mir modules

editThe Mir space station was constructed by connecting several Mir modules, each launched into orbit separately by the Proton rocket, except for the Docking Module, which was brought to Mir by the Space Shuttle.

| Module | Launch Date | Launch vehicle | Docking Date | Mass | Soyuz | Purpose | Configuration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core | February 19, 1986 | Proton 8K82K | N/A | 20,100 kg | N/A | Living quarters | |

| Kvant-1 | March 31, 1987 | Proton 8K82K | ~April 9, 1987 | 10,000 kg | TM-2 | Astronomy | |

| Kvant-2 | November 26, 1989 | Proton 8K82K | December 6, 1989 | 19,640 kg | TM-8 | Newer, more sophisticated life support systems. | |

| Kristall | May 31, 1990 | Proton 8K82K | June 10, 1990 | 19,640 kg | TM-9 | Technology, material processing, geophysics and astrophysics laboratory | |

| Spektr | May 20, 1995 | Proton 8K82K | June 1, 1995 | 19,640 kg | TM-21 | House experiments for the US-Russian Cooperation program. | |

| Docking Module | November 12, 1995 | STS-74 Atlantis | November 15, 1995 | 6,134 kg | TM-22 | Used as a docking port for the Space Shuttle. | |

| Priroda | April 23, 1996 | Proton 8K82K | April 26, 1996 | 19,000 kg | TM-23 | Remote sensing module |

Expeditions, spacewalks and crews

edit

Mir in popular culture

edit- Two amateur radio call signs, U1MIR and U2MIR, were assigned to Mir in the late 1980s, allowing radio operators on Earth to communicate with the cosmonauts. [1]

- The station played a prominent role as a refueling depot in Michael Bay's 1998 movie Armageddon (although it was referred to simply as the "Russian Space Station"). The station was "destroyed" in the movie following a fuel leak during the refueling. The lone Russian cosmonaut was said to have been on Mir for the prior 18 months.

- The station served a minor role as a refuge for S.R. Hadden in the 1997 movie adaptation of Contact.

- A confidence trickster Peter Llewellyn almost got a ride on Mir in 1999 after promising US$100 million for the privilege. [2]

- In the fictional game setting World of Darkness by White Wolf Publishing, MIR is the site of a Black Spiral Dancer Caern, serving as a direct portal to Malfeas.

- In the South Park episode "Pink Eye", Kenny's first death in the episode is that of Mir crashing on his body.

- Although it has little to do with the space station, there was a series a MMORPG's entitled "The Legend of Mir".

- In the pilot episode of the Showtime series Dead Like Me, the lead character George (Ellen Muth) was killed when Mir's zero-gravity toilet seat fell to earth and hit her.

- In anticipation of the reentry of Mir, the owners of Taco Bell towed a large target out into the Pacific Ocean. If the target was hit by a falling piece of Mir, every person in the United States would be entitled to a free Taco Bell taco. The company bought a sizable insurance policy for this "gamble."[3] No piece of the station struck the target.

- In episode 5F21 of The Simpsons, Homer has a flashback of himself sabotaging Mir[4], while in episode CABF03 the Simpsons family car is hit by a sturgeon from the space station [5].

- In the 1999 movie Virus, an alien lifeform invades Mir.

References

edit- ^ Astronaut Hams Astronaut Hams

- ^ No Mir flight for British businessman BBC News: May 27, 1999

- ^ Taco Bell press release March 19, 2001

- ^ Simpsons episode 5F21

- ^ Simpsons episode CABF03

See also

edit- Salyut

- Skylab

- Shuttle-Mir Program

- Asteroid 11881 Mirstation: named after the space station.

- Mir in popular culture