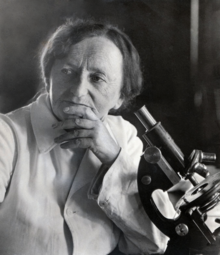

Sophia Getzowa (Hebrew: סופיה גצובה, 10 January 1872 (O.S.)/23 January 1872 (N. S.) – 11(12) July 1946) was a Belarusian-born pathologist and scientist in Mandatory Palestine. She grew up in a Jewish shtetl in Belarus and during her medical studies at the University of Bern, she became engaged to Chaim Weizmann, who would become the first president of Israel. Together they worked in the Zionist movement. After a four-year romance, Weizmann broke off their engagement and Getzowa returned to her medical studies, graduating in 1904. She carried out widely cited research on the thyroid, identifying solid cell nests (SCN) in 1907.

Sophia Getzowa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 January 1872 |

| Died | 11 July 1946 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | Russian Empire, Israeli |

| Other names | Sofija Gecova, Sofia Getsowa, Sophie Getzowa, Sophia Getzova, Sonia Getzowa |

| Occupation(s) | pathologist, academic |

| Years active | 1905–1940 |

| Known for | describing solid cell nests |

Because of her status as a Jew, a woman, and a foreigner, Getzowa's employment status was unstable. She worked through the 1920s in various locations in Switzerland and also briefly in Paris. In 1925, after a recommendation from Albert Einstein, she was hired to work as a pathologist in the yet to be created Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where she would become the first female professor in 1927. She collaborated with a wide range of European scientists over the remainder of her career, before her retirement in 1940.

Early life

editSophia (also Sonia) Getzowa (Gecova) was born on 23 January 1872 in Belarus, which at the time was part of the Russian Empire.[1][Notes 1] In 1874, her family resided in Svisloch, a shtetl in the Pale of Settlement,[7] near Novogrudok, which was also occasionally noted as her home town.[8] In her own account, Getzowa stated that her parents, Beila Gelfand-Romm of Vilinus and Beiness Getzow[15] (or Beinus Getsov, 1845–1896)[16] of Gomel, moved the family from the rural estate near Svisloch, where she was born, to Vilnius soon after her birth. When she was around four years old, they moved to Gomel, where three years later she began studying with a Jewish scholar and learned the Hebrew alphabet.[15]

Getzowa's mother died when she was eight and a cousin, Marie Scheindels-Kagan, who ran a school in Švenčionys took her in and taught her Russian orthography. She returned to Gomel in 1882 and entered the newly founded Progymnasium, where she studied for three years. For eight years,[15] she then attended the Жіночу гімназію в Ромнах (Women's Gymnasium in Romny), before pursuing medical studies at the University of Bern, in Switzerland,[1] beginning in 1895.[3] Getzowa was active in the Zionist movement and in 1898 was a delegate to the Second Zionist Congress, held in Basel.[17] That year, she became engaged to Chaim Weizmann, who took her to meet his family in Pinsk over the summer breaks in 1898 and 1899.[18] Getzowa traveled to Pinsk on both occasions, with her sister Rebekka, who was also studying medicine in Bern.[3] It is probable that the two lived together after their engagement, as was common at the time.[19]

Getzowa became an important member of the Zionist community,[20] attending the 5th Zionist Congress as a delegate of the Democratic Fraction,[18][21] a radical group formed by her friend Leo Motzkin and Weizmann in 1901.[22] Weizmann, who had been simultaneously carrying on a relationship with his future wife, Vera Khatzman, broke off his four-year engagement with Getzowa in July 1901, but did not tell his family until March 1903.[23][24] Because Weizmann was vague about his intention, promising to meet Getzowa three months later and encouraging her to continue to work with him in the Zionist movement, she interpreted his relationship with Vera as a flirtation.[24]

Having been westernized by his long exposure to European cultures in Germany and Switzerland, Weizmann had now decided on a partner who was less defined by Eastern Jews in the confines of the shtetle.[25] His behavior was seen as dishonorable, and created fractures with Motzkin and others in the Democratic Fraction.[23] His fellow students held mock-court proceedings and ruled that he should uphold his commitment and marry Getzowa, even if he later divorced her.[26] She never recovered from the trauma of the break-up, suffering yet another blow when her sister died from abdominal cancer on 16 April 1902.[27] Encouraged by her professors to continue her studies, she graduated with a medical degree in 1904.[1][20] In researching her thesis, Über die Thyreoidea von Kretinen und Idioten (On the Thyroid Glands of Cretins and Idiots), she discovered foreign tissue elements, which would become the foundation of her career.[28] Her observation was that cell rests and cysts of the postbranchial body in atrophic goiters of the thyroid were not formed from thyroid tissue and did not react with the thyroid.[29]

Career

editIn 1905, Getzowa was hired by Professor Hans Strasser as first female assistant at the Bern Institute of Anatomy.[8][30][31] She began analysis of goiters and parathyroid tissues and along with Langhans and other of his students was one of the key researchers who clarified the origin of thyroid tumors.[32][33] She continued with her studies, this time at the Institute of Pathology, under the direction of Theodor Langhans and Ernst Hedinger,.[1] Thanks to her pleasant demeanor, she was popular with her fellow students and colleagues. In 1907, Carl Wegelin was so impressed by her removal of a tumor by abdominal incision that he developed a close professional relationship with her.[34] Wegelin later became the first president of the Swiss Academy of Medicine.[35][36] That same year, she discovered solid cell nests (SCN), becoming the first to describe them.[37] As Langhans was nearing retirement, he prepared for his departure and both Wegelin and Getzowa were encouraged to apply for the post. Wegelin had habilitated in 1908[36] and Langhans used Getzowa's research to grant her Habilitation in 1912.[1][38][36] Though seven years younger than Getzowa, Wegelin succeeded Langhans as director of the Anatomical institute.[36] and she was appointed as a Privatdozent at the University of Bern.[38]

In 1913, Getzowa was appointed first assistant at the Institute and with the beginning of World War I in 1914, she stood in for the director who had been called to military duty. After two years of service, as a woman and a foreigner she was dismissed in October 1915.[39] Without any income, her previous professor Ernst Hedinger offered her a post at the University of Basel in 1916.[38][39] The position ended after nine months and she became the prosector at the Kantonsspital St. Gallen on a recommendation from Wegelin. Over the next two years, she worked in the pathology clinic where she performed abdominal operations.[39][40] When the war ended, Getzowa was cut off from friends and family in her former homeland. The Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921) devastated what was left of her home and annexed the land as part of the Second Polish Republic. She returned to Bern, and experienced both emotional and financial difficulties, which did not dissipate until 1921 when the American Putman-Jacoby Foundation arranged for her to work as a freelance researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. Given an opportunity to come back to Bern, she returned to work at the Institute in 1924. The following year was awarded special retroactive remuneration for teaching experimental pathology at the university.[11]

At the time she left Paris, Getzowa learned of another opening, that of working for the Hadassah Women's Zionist Organization of America in a pathology institute in Eretz Yisrael, but she was unsure of its financial reliability as there was a dispute between the Swiss officials who were providing the chairs for the medical facility and the Palestinian bankers. She sought advice from Albert Einstein and he wrote to the authorities in Jerusalem recommending her and suggesting they offer reasonable, well-defined conditions.[41] Getzowa, reluctantly, also asked Chaim Weizmann for support, as it was he who was involved in founding a Jewish university in Jerusalem. Weizmann replied half a year later, supporting her desire to receive a post of pathologist but explaining administrative structures first needed to be established.[42]

Finally matters were sorted out and Getzowa was engaged as a pathological specialist. She set sail on a steamer in the autumn of 1925, having been appointed director of an as yet non-existent pathological institute to be located at the Rothschild Hadassah Hospital.[42] In 1927, Getzowa became the first female professor of Israel, when she was appointed as a lecturer of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[43] She began working at hospitals in Tel Aviv, undertaking abdominal examinations which in some cases identified tumors in need of removal. The operations upset orthodox Jews who smashed her laboratory windows. In 1931, Getzowa returned to Basel, seeking international support to complete the pathological institute, visiting her European friends, and keeping up with pathological practice. In 1933, the death in Paris of her friend, colleague and financial supporter, Leo Motzkin, caused Getzowa to fall into a deep depression.[42]

In 1939, Getzowa returned to Jerusalem, where her pathology center had been completed as an addition to the Hadassah Hospital on Mount Scopus. The administration of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem refused to recognize her as a professor, taking no account of her background in Bern[44] or the 13 years she had already spent working for Palestine. She was offered the chance to obtain a habilitation in Jerusalem but she refused, maintaining it would take years off her career. On 1 February 1939, the university asked for her resignation. Calling on support from international colleagues, Getzowa obtained references for the rector of the university, Abraham Fraenkel, and requests asking him to reconsider her application. Three months later, on 19 February 1940, Fraenkel granted her status as a professor emeritus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.[45]

Contribution to research

editAs documented in her 1907 paper titled ""Über die Glandula parathyreoidea, intrathyreoideale Zellhaufen derselben und Reste des postbranchialen Körpers", Getzowa was the very first to identify Zellhaufen or solid cell nests (SCN). They have long been of interest to pathologists as it is thought they could be behind ectopic structures in thyroid glands or in thyroid tumors.[46][47] Recent studies have indicated the importance of SCN as they have been found in at least three percent of routinely examined thyroids.[48] Her work in connection with the thyroid also led to research on the relationship between Riedel's struma and remnants of the post-branchial body, such as that conducted by Louise H. Meeker as early as 1924. Credit is specifically given to Getzowa for the detailed descriptions of the ultimo-branchial body in seven individuals she made in her 1905 paper titled "Über die Thyreoidea von Kretinen und Idioten".[49]

Death and legacy

editGetzowa died on 11 or 12 July 1946 in Jerusalem,[2][38][45] where she was buried in the Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery.[6] In Palestine, she was considered to have been a pioneer in pathology, undertaking autopsies and examinations throughout the country over many years.[50]

Published works

edit- Getzowa, Sophia (April 1905). "Über die Thyreoidea von Kretinen und Idioten". Virchows Archiv (in German). 180 (1): 51–98. doi:10.1007/BF01967777.

- Getzowa, Sophia (May 1907). "Über die Glandula parathyreoidea, intrathyreoideale Zellhaufen derselben und Reste des postbranchialen Körpers". Virchows Archiv (in German). 188 (2): 181–235. doi:10.1007/BF01945893.

- Getzowa, Sophia (August 1911). "Zur Kenntnis des postbranchialen Körpers und der branchialen Kanälchen des Menschen". Virchows Archiv (in German). 205 (2): 208–257. doi:10.1007/BF01989433.

- Getzowa, S.; Stuart, G.; Krikorian, K. S. (1933). "Pathological changes observed in paralysis of the landry type: A contribution to the histology of neuro‐paralytic accidents complicating antirabic treatment". The Journal of Pathology. 37 (3): 483–500. doi:10.1002/path.1700370315.

- Getzowa, S.; Sadowsky, A. (June 1950). "On the Structure of the Human Placenta with Full‐Time and Immature Foetus, Living or Dead". The Journal of Pathology. 57 (3): 388–396. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1950.tb05251.x. PMID 15428922.

Notes

edit- ^ The University of Bern faculty roster indicates Getzowa was born in Vilnius.[1] Some records indicate that she was born in Gomel[2][3] or Minsk,[4] or a small town near Minsk,[5] which are now in Belarus.[2] Her tombstone reads "6th of Tishrei, 5633–12th of Tammuz 5706, corresponding to 8 October 1872 as the date of her birth.[6] Other sources indicate she was born in 1874 in Svisloch, near Minsk.[7] Still other sources indicate she grew up in Novogrudok,[8] located in the Grodno Region. This region was originally part of Lithuania and had a high concentration of Jewish settlers.[9] There was also a Jewish village known as Svisloch, in the region.[10] Rogger states that at the end of World War I, Getzowa was cut off from her family as their home in Belarus had been annexed by Poland. This would seem to indicate, since the Treaty of Riga divided Belarus west of Minsk to Poland and east of Minsk to Russia, that she was from the western part of the country.[11] On the other hand, Gomel, cited by Rogger,[3] is close to Mogilev, another city given as her place of origin.[12] In the Mogilev Region there was yet another Jewish settlement known as Svisloch.[13] These eastern locations are nearer Romny, Ukraine, where Getzowa attended gymnasium.[1] Getzowa's own account of her origin varies. In a curriculum vitae created in 1904, she stated she was "geboren am 23 (10) Januar 1872" in Gomel, (noting both old and new style dates);[14] however, in her 1925 CV, she stated she was "geboren in Januar 1872" on a country estate near Svisloch, lived her first four years in Vilnius and then moved with her family to Gomel.[15]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g University of Bern 1965, p. 441.

- ^ a b c Boschung 2008, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d Rogger 1999, p. 199.

- ^ Litvinoff 1982, p. 1.

- ^ Teveth 1988, p. 255.

- ^ a b Mount of Olives Cemetery 2016.

- ^ a b Neumann 1987, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Nieuw Israëlietisch Weekblad 1905, p. 9.

- ^ Renck 1999.

- ^ Beit Hatfutsot 1996.

- ^ a b Rogger 1999, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Doerr & Roßner 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Spector & Wigoder 2001, pp. 1269–1270.

- ^ Getzowa 1904, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Getzowa 1925, p. 1.

- ^ Belarus Deaths Database 1896.

- ^ Einhorn 1944, p. 151.

- ^ a b Rose 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Cooper 1995, p. 188.

- ^ a b Raphael 1985, p. 2.

- ^ Center for Israel Education 2015, p. 40.

- ^ Klausner 2008.

- ^ a b Rose 1986, p. 56.

- ^ a b Rogger 1999, p. 200.

- ^ Reinharz 1983, p. 211-212.

- ^ Hirsch 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Rogger 1999, p. 202.

- ^ Rogger 1999, p. 203.

- ^ Cowdry 1932, p. 803.

- ^ Boschung 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Rogger 2002, p. 118.

- ^ Crotti 1918, pp. 58, 76, 445.

- ^ Pool 1907, pp. 519–525.

- ^ Rogger 1999, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Boschung 2012.

- ^ a b c d Rogger 1999, p. 205.

- ^ Bychkov 2017.

- ^ a b c d Journal of the American Medical Association 1946, p. 237.

- ^ a b c Rogger 1999, p. 206.

- ^ Berblinger, Dietrich & Herxheimer 2013, p. 280.

- ^ Rogger 1999, p. 208.

- ^ a b c Rogger 1999, p. 209.

- ^ Scopus 2016, p. 7.

- ^ Rogger 1999, p. 210.

- ^ a b Rogger 1999, p. 211.

- ^ Rios Moreno; María José; et al. (22 March 2011). "Inmunohistochemical Profile of Solid Cell Nest of Thyroid Gland". Endocrine Pathology. 22 (1). Springer: 35–39. doi:10.1007/s12022-010-9145-4. PMC 3052464. PMID 21234707.

- ^ Bychkov, Andrey (September 2015). "Thyroid gland, Congenital anomalies, Solid cell nests". PathologyOutline.com. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Asioli, Sofia (October 2009). "Solid Cell Nests in Hashimoto's Thyroiditis Sharing Features with Papillary Thyroid Microcarcinoma". Endocrine Pathology.

- ^ Meeker, Louise H. (1925). "Riedel's Struma Associated with Remnants of the Post-Branchial Body". American Journal of Pathology. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ Archives of Pathology 1946, p. 658.

Bibliography

edit- Berblinger, W.; Dietrich, A.; Herxheimer, G.; et al. (2013). Drüsen mit innerer Sekretion. Handbuch der Speziellen Pathologischen Anatomie und Histologie (in German). Vol. 8 (Reprint of 1926 1st ed.). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-642-47987-8.

- Boschung, Urs, ed. (2008). Von der Geselligkeit zur Standespolitik: 200 Jahre Ärztegesellschaft des Kantons Bern (PDF) (in German). Bern, Switzerland: Ärztegesellschaft des Kantons Bern. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2018.

From sociability to professional politics: 200 years of the medical society of the canton of Bern

- Boschung, Urs (13 August 2012). "Wegelin, Carl". Historischen Lexikon der Schweiz (in German). Bern, Switzerland: Swiss Academy of Humanities and Social Sciences. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Bychkov, Andrey (23 February 2017). "Thyroid gland Congenital anomalies: Solid cell nests". pathologyoutlines.com. Bingham Farms, Michigan: PathologyOutlines. Archived from the original on 28 April 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- Cooper, John (1995). "Jewish Sexual Attitudes in Eastern Europe 1850-1920". In Magonet, Jonathan (ed.). Jewish Explorations of Sexuality. Providence, Rhode Island: Berghahn Books. pp. 181–190. ISBN 978-1-57181-868-3.

- Cowdry, Edmund V., ed. (1932). Special Cytology—The Form and Functions of the Cell in Health and Disease: A Textbook for Students of Biology and Medicine (PDF). Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York, New York: Paul B. Hoeber, Inc. OCLC 3164917.

- Crotti, André (1918). Thyroid and Thymus. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lea & Febiger. OCLC 11525746.

- Doerr, W.; Roßner, J. A. (2013). Toxische Arzneiwirkungen am Herzmuskel : cardiovasculäre Therapie aus der Sicht der pathologischen Anatomie (in German). Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-08604-8.

- Einhorn, Moses, ed. (1944). "Dr. Sophia Getzowa". Ha-Rofe Ha-ʻivri. New York City, New York: The Hebrew Medical Journal. ISSN 0099-0825.

- Getzowa, Sophia (1904). Curriculum vitae fuer Doktorat (Report) (in German). Bern, Switzerland: University of Bern.

"geborn am 23 (10) Januar 1872 in der Stadt Gomel" (born on 23(10) January 1872 in the town of Gomel.)

- Getzowa, Sophia (3 December 1925). Curriculum vitae (Report) (in German). Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

"Ich, Tochter des Bürgers zu Gomel Beiness Getzow, dessen Eltern (Getzow-Tschlenaw) und Grosseltern aus Minsk stammen, und der Beila Gelfand-Romm, derer Ahnen in vielen Generationen in Wilna wohnten, bin auf einem Landgut neben Sweslatsch im Januar 1872 geboren und verbrachte meine ersten vier Lebensjahre in Wilna, von wo aus meine Eltern nach Gomel" (I, daughter of the citizen of Gomel, Beiness Getzow, whose parents (Getzow-Tschlenaw) and grandparents come from Minsk, and Beila Gelfand-Romm, whose ancestors lived for many generations in Vilnius, was born on an estate next to Svislach in January 1872 and spent my first four years of life in Vilnius, from where my parents moved to Gomel.)

- Hirsch, Luise (2013). From the Shtetl to the Lecture Hall: Jewish Women and Cultural Exchange. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-5993-2.

- Klausner, Israel (2008). "Democratic Fraction". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Chevy Chase, Maryland: Encyclopaedia Judaica. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- Litvinoff, Barnet, ed. (1982). The essential Chaim Weizmann: the man, the statesman, the scientist. London, England: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-78155-4.

- Neumann, Daniela (1987). Studentinnen aus dem Russischen Reich in der Schweiz (1867-1914) (in German). Zürich, Switzerland: H. Rohr. ISBN 978-3-85865-627-8.

- Pool, Eugene H. (July 1907). "Tetany Parathyreopriva". Annals of Surgery. 46 (1). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J. B. Lippincott Company: 507–540. doi:10.1097/00000658-190710000-00002. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1414406. PMID 17862043.

- Raphael, Chaim (30 June 1985). "The Youth of the Father of His Country". The New York Times. New York City, New York. Archived from the original on 25 November 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- Reinharz, Jehuda (April 1983). "Chaim Weizmann: The Shaping of a Zionist Leader before the First World War". Journal of Contemporary History. 18 (2): 205–231. doi:10.1177/002200948301800203. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260385.

- Renck, Ellen Sadove (1999). "History of Grodno". jewishgen.org. Belarus: Belarus SIG. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- Rogger, Franziska (1999). "Sophie Getzowa: Von Albert Einstein unterstutzt, von Chaim Weizmann geliebt und verlassen". Der Doktorhut im Besenschrank: das abenteuerliche Leben der ersten Studentinnen—am Beispiel der Universität Bern. Bern, Switzerland: eFeF-Verlag. pp. 198–211. ISBN 978-3-905561-32-6.

- Rogger, Franziska (2002). "Kropfkampagne, Malzbonbons und Frauenrechte: Zum 50. Todestag der ersten Berner Schulärztin Dr. med. Ida Hoff, 1880–1952" [Goiter campaign, malt sweets and women's rights: On the 50th anniversary of the first Bernese school doctor med. Ida Hoff, 1880–1952] (PDF). Berner Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Heimatkunde (in German). 64 (3): 101–119. ISSN 0005-9420. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Rose, Norman (1986). Chaim Weizmann: A Biography. New York, New York: Viking Penguin, Inc. ISBN 978-0-670-80469-6.

- Spector, Shmuel; Wigoder, Geoffrey (2001). The Encyclopedia of Jewish Life Before and During the Holocaust. Vol. 3: Seredina-Buda—Z. New York, New York: New York University Press for the Research Associate Institute of Contemporary Jewry. ISBN 978-0-8147-9378-7.

- Teveth, Shabtai (April 1988). "Reviewed Work: Chaim Weizmann: The Making of a Zionist Leader by Jehuda Reinharz". Middle Eastern Studies. 24 (2): 254–257. doi:10.1080/00263208808700741. ISSN 0026-3206. JSTOR 4283239.

- Beinus Getsov (Report). Gomel, Mogilev Guberniya, Belarus: Belarus Deaths Database. 18 September 1896. record M172.

age: 51, father: Leiba Getsov, cause of death: cancer tumor, occupation: Gomel petty bourgeois

- "Biographical Index" (PDF). israeled.org. Atlanta, Georgia: Center for Israel Education. June 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- "Buitenland" [Abroad]. Nieuw Israëlietisch Weekblad (in Dutch). No. 5665. Amstelveen, The Netherlands. 16 June 1905. p. 9. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 21 October 2018.

- "Deaths: Sophia Getzowa". Archives of Pathology. 42. Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association. 1946. ISSN 0003-9985.

- "Dozenten uni bern" [Teachers of the University of Bern] (PDF). biblio.unibe.ch. Bern, Switzerland: University of Bern. 25 April 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Palestine: Death of Professor Sophia Getzowa". Journal of the American Medical Association. 132 (4): 237. 28 September 1946. doi:10.1001/jama.1946.02870390053017d.

- "סופיה גצובה" [Sophia Getzova] (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery. 14 June 2016. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Svisloch". Tel Aviv, Israel: The Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot. 1996. Retrieved 17 November 2018.

- "United in the Great Common Task of Searching for Truth" (PDF). Scopus: The Magazine of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Vol. 62. Jerusalem: Hebrew University of Jerusalem. 2016. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2018.