The Battle of New Market was fought on May 15, 1864, in Virginia during the Valley Campaigns of 1864 in the American Civil War. A makeshift Confederate army of 4,100 men defeated the larger Army of the Shenandoah under Major General Franz Sigel, delaying the capture of Staunton by several weeks.

| Battle of New Market | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

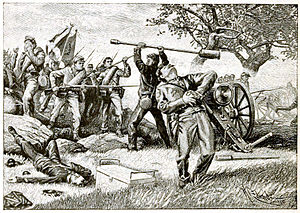

"Cadets at New Market" | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Franz Sigel | John C. Breckinridge | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 6,275[1] | 4,087[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

96 killed 520 wounded 225 captured/missing |

43 killed 474 wounded 3 captured/missing | ||||||

The battle is primarily remembered today for being the only time in American history a school's student body was used as an organized combat unit.[3] During the battle Confederate general John C. Breckinridge ordered cadets from the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), some of them child soldiers no older than 15, to join an attack on the Union lines.[4][5] The event has gone on to become central to many of the institute's myths and traditions.

Background

editIn the spring of 1864, Union commander-in-chief Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant set in motion a grand strategy designed to press the Confederacy into submission. Control of the strategically important and agriculturally rich Shenandoah Valley was a key element in Grant's plans. While he confronted General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia in the eastern part of the state, Grant ordered Major General Franz Sigel's army of 10,000 to secure the valley and threaten Lee's flank, starting the Valley Campaigns of 1864.[citation needed]

Sigel was to advance on Staunton, Virginia, in order to link up with another Union column, commanded by George Crook, which would advance from West Virginia and destroy the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad and other Confederate industries in the area. Sigel's force totaled about 9,000 men and 28 cannons, divided into an infantry division commanded by Brigadier General Jeremiah C. Sullivan and a cavalry division commanded by Major General Julius Stahel (detachments made during the campaign reduced the Union force to about 6,300 by the time of the battle).[6]

Receiving word that the Union Army had entered the valley, Major General John C. Breckinridge pulled together all available forces to repulse the latest threat. His command consisted of two infantry brigades under John C. Echols and General Gabriel C. Wharton, a cavalry brigade commanded by General John D. Imboden, and other independent commands. This included the cadet corps of VMI, which had an infantry battalion of 247 cadets commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Scott Shipp and a two-gun artillery section. Breckinridge concentrated his infantry at Staunton, while Imboden slowed Sigel's movement southward along the valley.[7]

On the morning of May 13, Breckinridge decided to move north to attack Sigel instead of waiting for Sigel to reach Staunton. By the evening of May 14, Sigel's advance forces had reached a position north of the village of New Market, while Breckinridge was at Lacey Spring eight miles south of New Market. The Confederates started toward the Union positions at 1:00 a.m. on May 15, hoping to trap and crush the Union army.[8]

Opposing forces

editUnion

editConfederate

editBattle

editOn May 14 a delaying action was fought at Rude's Hill, just outside of Mt. Jackson, by elements of the Confederate 18th Virginia Cavalry, under the overall command of Colonel John Imboden. The Confederate cavalry slowed the Union advance, enabling Breckinridge to gather the main body of his Confederate forces at New Market, about 4 miles away.[citation needed]

The two forces made contact south of New Market about mid-morning, with the main Union line west of the town near the North Fork of the Shenandoah River; Colonel Augustus Moor initially commanded the Union forces present on the battlefield at this time, which consisted of his infantry brigade and part of John E. Wynkoop's cavalry brigade. Additional Union regiments arrived throughout the morning and deployed between the North Fork of the Shenandoah River and the Valley Turnpike, with the main line centered on Manor's Hill. Breckinridge deployed Wharton's brigade on the Confederate left west of the Valley Turnpike and Echols's brigade on the right along the Pike; Echols was ill that morning, so his brigade was commanded by Colonel George S. Patton, Sr. The VMI cadets battalion was kept in reserve, while Imboden's cavalry was east of the turnpike.[9]

Breckinridge attempted to lure the Federals into attacking him using cavalry and artillery, but Moor refused to move from his position. At about 11:00 a.m., Breckinridge decided to launch an attack on Moor using his infantry, while Imboden's brigade crossed Smith's Creek east of New Market, rode north, and recrossed the stream behind the Union lines. Union cavalry general Stahel arrived at New Market at this time with additional troops, followed shortly afterwards by Union general Sigel.[10]

Breckinridge launched his infantry attack near noon, slowly pushing Moor's infantry brigade off Manor's Hill and northward toward the rest of Sigel's army, which was deploying on a hill north of Jacob Bushong's farm, known as Bushong's Hill. Once past the town of New Market, the Confederates halted to dress ranks, shift units along the line, and reposition their artillery units. Breckinridge resumed his attack at about 2:00 p.m.[11] As the Confederate line formed near the Bushong farm, massed Union rifle and artillery fire disorganized the Confederate units in the center, forcing the right wing of the 51st Virginia Infantry and the 30th Virginia Infantry Battalion to retreat in confusion, while the rest of the Confederate line stalled.[citation needed]

Breckinridge reluctantly ordered the VMI cadet battalion to fill the gap; while the battalion was moving forward to the Bushong orchard, Shipp was wounded and was replaced by Captain Henry A. Wise. At this time, Sigel launched two counterattacks. On the Union left, Stahel launched a mounted charge with the cavalry but was routed by heavy fire from Confederate artillery, while three infantry regiments attacked on the Union right and were repulsed as well.[12] The main cause of the failure of the infantry attacks was confusion within the ranks of the Union commanders; Sigel was noted to be shouting orders in his native language of German.[citation needed]

After the repulses of the Union attacks, Breckinridge started his advance again shortly after 3:00 p.m. with his infantry force; while crossing a field near Bushong's orchard, several VMI cadets lost their shoes in the mud, which led to the field being called the "Field of Lost Shoes". As the Confederate line got closer to the Union artillery, Sigel's batteries were forced to retreat as the infantry started breaking towards the rear. Five cannons were abandoned to the Confederates, one of which was captured by the VMI cadet battalion. Battery B of the 5th U.S. Artillery, which had just arrived on the field, and two infantry regiments slowed the Confederate pursuit.[13] At this time, Breckinridge halted his forces until the supply trains arrived to resupply the troops.[citation needed]

While the infantry was being resupplied, Confederate cavalry general Imboden arrived with his brigade with the news that the creek was too swollen to be crossed. Union general Sullivan arrived during this time with the 28th and 116th Ohio infantry; Sigel managed to organize a rearguard on Rude's Hill, with Sullivan's infantry east of the turnpike, some of Stahel's cavalry west of the road, and the artillery behind the line. Due to the exhaustion of the men and low ammunition, Sigel decided to retreat across the Shenandoah River to Mount Jackson. Breckinridge advanced his artillery to the crest of Rude's Hill where they shelled Sigel's retreating Federals. The Union army managed to cross Mill Creek at Mt. Jackson and burned the bridge before the Confederates could catch up.[14]

Aftermath

editUnion casualties totaled 841 for the battle: 96 killed, 520 wounded, and 225 captured or missing, a casualty rate of 13.4%. The Confederates lost 43 killed, 474 wounded, and 3 missing, 13% of the army. The wounded from the battle were cared for in Bushong's barn and in the town at the Smith Creek Baptist church and a warehouse, while the dead were buried in the graveyard of St. Matthew's Lutheran Church.[15]

Sigel staged a rapid retreat northward to Strasburg, leaving the field and the Valley to Breckinridge's army. After learning of the Union defeat, Grant became furious and replaced Sigel with General David Hunter; Sigel was assigned to command the department's reserve division based in Harpers Ferry.[16] Sergeant James Burns of the 1st West Virginia Infantry received the Medal of Honor in 1896 for saving the regimental flag in the battle.[17]

The Confederate victory allowed the local crops to be harvested for Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and protected Lee's lines of communications to western Virginia. The Virginia newspapers and the Confederate soldiers in the battle compared Breckinridge to Stonewall Jackson. Following Sigel's retreat, Lee suggested that Breckinridge follow the Union army and invade Maryland; however, the flooded rivers in the northern Shenandoah Valley and the length of his supply line prevented Breckinridge from making a pursuit. Breckinridge's forces were transferred to eastern Virginia, where they reinforced Lee's army at the Battle of Cold Harbor.[18]

The victory failed to stop the Union offensive, however. After assuming command of the Army of the Shenandoah, Hunter resumed the march southwest and defeated a Confederate force under Brig. Gen. William E. "Grumble" Jones at the Battle of Piedmont on June 5, occupying Staunton the following day.[citation needed]

VMI casualties

editOf the 247 VMI cadets at the battle, there were 60 casualties (around 24%),[19] with five cadets killed in action, five more dying later of wounds received, and 50 others wounded in action but surviving.[20] Eight VMI staff also accompanied the cadets and the Commandant, Scott Shipp, was wounded in action as well.

The New Market Day ceremony is an annual observance held at VMI in front of the monument Virginia Mourning Her Dead, a memorial to the New Market Corps. It was sculpted by Cavaliere Moses Ritter von Ezekiel, VMI Class of 1866, who was a veteran of the battle. The names of all of the cadets in the Corps of 1864 are inscribed on the monument, and six of the ten cadets who died are buried at this site.

The ceremony features the roll call of the names of the cadets who lost their lives at New Market, a custom that began in 1887. As the name of each cadet who died is called, a representative from the same company in the modern Corps answers, "Died on the Field of Honor, Sir." A 3-volley salute is conducted by a cadet honor guard, followed by "Taps" played over the parade ground. To culminate this ceremony, the entire Corps passes Virginia Mourning Her Dead in review.[21]

Battlefield preservation

editThe battlefield is primarily preserved in the 300-acre New Market Battlefield State Historical Park. In addition, the Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 20 acres (0.081 km2) of the battlefield.[22]

In popular culture

editIn fall 1923, under the direction of Marine Corps Brigadier General Smedley Butler and employing the Quantico marines, the battle was reenacted on its historical grounds. The number of spectators was estimated at over 150,000.[23]

John Ford's 1959 film The Horse Soldiers includes a scene which is loosely based on the event.[citation needed]

A principal character in Elaine Marie Alphin's 1991 novel Ghost Cadet is the ghost of VMI cadet William Hugh McDowell, who was killed in the battle.[24]

Sean McNamara's 2014 film, Field of Lost Shoes, is a fictionalized account of the actions performed by VMI cadets during the battle. The movie follows a group of seven VMI cadets, based on real characters.[citation needed]

References

edit- ^ Davis, p. 190.

- ^ Davis, p. 192.

- ^ "Battle of New Market". The Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ P.W. Singer. "The Enablers of War: Casual Factors behind the Child Soldier Phenomenon" (PDF). The Brookings Institution.

Child soldiers even fought in our own civil war, most notably when a unit of 247 Virginia Military Institute cadets fought with the Confederate Army in the battle of New Market (1864).

- ^ "America's Racial Awakening Forces Virginia Military Institute To Confront Its Past – And Future". Time. May 27, 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

In May 1864, 257 cadets, some as young as 15, marched 80 miles to the Battle of New Market, Va., in what is believed to be the only time in U.S. history a college's student body has fought as a combat unit. Forty-five were wounded and 10 died.

- ^ Davis, pp. 18–20, 24.

- ^ Knight, pp. 77, 246–248.

- ^ Knight, p. 89, 100, 117.

- ^ Knight, pp. 118, 121–124.

- ^ Davis, p. 80–83, 87–88; Knight, pp. 129–180.

- ^ Knight, p. 136, 141–142; Davis, p. 102–103.

- ^ Davis, pp. 114–1120, 124–126, 128–130.

- ^ Davis, pp. 130–146.

- ^ Davis, pp. 146–152.

- ^ Davis, pp. 158–159, 194, 196.

- ^ Davis, pp. 157, 164–166.

- ^ Knight, p. 203.

- ^ Davis, pp. 179–184.

- ^ Knight, p. 246.

- ^ "VMI Cadets". www.history.army.mil. Retrieved November 16, 2024.

- ^ Davis, pp. 174–176.

- ^ "Saved Land". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ Hans Schmidt, Maverick Marine: General Smedley D. Butler and the Contradictions of American Military History (Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1998), p. 136.

- ^ "Ghost Cadet by Elaine Marie Alphin". Good Reads. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

Sources

edit- Davis, William C. The Battle of New Market. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1975.

- Knight, Charles, Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market, New York: Savas Beatie, 2010, ISBN 978-1-932714-80-7.

- National Park Service battle description

- Cadet Deaths at New Market – VMI Archives

- CWSAC Report Update

Further reading

edit- Couper, William. The Corps Forward: The Biographical Sketches of the VMI Cadets Who Fought in the Battle of New Market. Buena Vista, VA: Mariner Pub., 2005.

- Davis, William C., The Battle of New Market, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1993, ISBN 0-8117-0576-5.

- Du Pont, H.A., Col.,The Battle of New Market, Virginia, May 15, 1864, Winterthur, DE, 1923

- Knight, Charles, Valley Thunder: The Battle of New Market, New York: Savas Beatie, 2010, ISBN 978-1-932714-80-7.

- Pancake, John, "Virginia Reveres Civil War Bravery", Washington Post, November 26, 2008.

- Whitehorne, Joseph W.A. (1988). Battle of New Market – U.S. Army Self-Guided Tour. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-24.