Vanity Fair (British magazine)

Vanity Fair was a British weekly magazine that was published from 1868 to 1914. Founded by Thomas Gibson Bowles in London, the magazine included articles on fashion, theatre, current events as well as word games and serial fiction. The cream of the period's "society magazines", it is best known for its witty prose and caricatures of famous people of Victorian and Edwardian society, including artists, athletes, royalty, statesmen, scientists, authors, actors, business people and scholars.[1][2]

Taking its title from Thackeray's popular satire on early 19th-century British society, Vanity Fair was not immediately successful and struggled with competition from rival publications. Bowles then promised his readers "Some Pictorial Wares of an entirely novel character", and on 30 January 1869, a full-page caricature of Benjamin Disraeli appeared. This was the first of over 2,300 caricatures to be published. According to the National Portrait Gallery in London, "Vanity Fair's illustrations, instantly recognizable in terms of style and size, led to a rapid increase in demand for the magazine. It gradually became a mark of honour to be the 'victim' of one of its numerous caricaturists. Bowles's witty accompanying texts, full of insights and innuendoes, certainly contributed towards the popularity of these images".[2]

History

editWhen the history of the Victorian Era comes to be written in true perspective, the most faithful mirror and record of ... the spirit of the times will be sought and found in Vanity Fair.

Subtitled "A Weekly Show of Political, Social and Literary Wares", it was founded in 1868 by Thomas Gibson Bowles, who aimed to expose the contemporary vanities of Victorian society. Colonel Fred Burnaby provided £100 of the original £200 capital, and inspired by Thackeray's popular satire on early 19th-century British society suggested the title Vanity Fair.[3] The first issue appeared in London on 7 November 1868. It offered its readers articles on fashion, current events, the theatre, books, social events and the latest scandals, together with serial fiction, word games and other trivia.[2][4]

Bowles wrote much of the magazine himself under various pseudonyms, such as "Jehu Junior", but contributors included Lewis Carroll, Arthur Hervey, Willie Wilde, Jessie Pope, P. G. Wodehouse (who also wrote for the unrelated Condé Nast magazine of the same name) and Bertram Fletcher Robinson (who was editor from June 1904 to October 1906).[5] Lewis Carroll created a series of word ladder puzzles, which he then called "Doublets", which first appeared in the 29 March 1879 issue.[6]

Thomas Allinson bought the magazine in 1911 from Frank Harris, by which time it was failing financially. He failed to revive it and the final issue of Vanity Fair appeared on 5 February 1914, after which it was merged into Hearth and Home.[4]

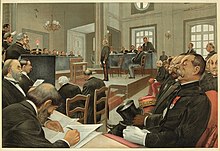

Caricatures

editA full-page, colour lithograph of a contemporary celebrity or dignitary appeared in most issues, and it is for these caricatures that Vanity Fair is best known then[7] and today.[3] Subjects included artists, athletes, royalty, statesmen, scientists, authors, actors, soldiers, religious personalities, business people and scholars. More than two thousand of these images appeared, and they are considered the chief cultural legacy of the magazine, forming a pictorial record of the period. They were produced by an international group of artists, including Sir Max Beerbohm, Sir Leslie Ward (who signed his work "Spy" and "Drawl"), the Italians Carlo Pellegrini ("Singe" and "Ape"), Melchiorre Delfico ("Delfico"), Liborio Prosperi ("Lib"), the Florentine artist and critic Adriano Cecioni, the French artists James Tissot ("Coïdé"), Prosper d'Épinay ("Nemo") and the American Thomas Nast.[2]

Image gallery

edit-

The Duke of Abercorn by Carlo Pellegrini ("Ape") in the 25 September 1869 issue

-

Benjamin Disraeli by Carlo Pellegrini in the 30 January 1869 issue

-

Mansur Ali Khan of Bengal by Alfred Thompson ("Ἀτη") in the 16 April 1870 issue

-

William Thomson, Archbishop of York, by Carlo Pellegrini in the 24 June 1871 issue

-

Charles Darwin by James Tissot ("Coïdé") in the 30 September 1871 issue

-

Caricature of Midhat Pasha by Leslie Ward ("Spy") in the 30 June 1877 issue

-

Thomas Hardy caricature by Leslie Ward in the 4 June 1892 issue

-

Captioned "Old Bones", caricature of an elderly Richard Owen in 1873

-

Alexandre Dumas fils by Théobald Chartran in the 27 December 1879 issue

-

Captioned "Steel", Sir Henry Bessemer by Leslie Ward in the 6 November 1880 issue

-

Rudyard Kipling by Leslie Ward on 7 June 1894

-

President Paul Kruger of the South African Republic by Leslie Ward in the 8 March 1900 issue

-

Suffragette Christabel Pankhurst in the 15 June 1910 issue

-

Queen Alexandra (unsigned) in the 7 June 1911 issue

-

William Gillette playing Sherlock Holmes, drawn by Leslie Ward in the 27 February 1907 issue

-

Henrik Ibsen by "Snapp" in the 12 December 1901 issue

-

Oscar Wilde by Carlo Pellegrini in issue 812, April 1884

-

Caricature of golfer Horace Hutchinson by Leslie Ward on 19 July 1890

-

Caricature of Henry Irving in the melodrama The Bells, in the 19 December 1874 issue

-

Caricature of Pierre and Marie Curie in the 22 December 1904 issue

-

W. S. Gilbert by Leslie Ward, published on 21 May 1881

-

Winston Churchill by Leslie Ward, 27 September 1900

-

Mark Twain by Leslie Ward on 13 May 1908

-

Captioned "Boy Scouts", Robert Baden-Powell in the 19 April 1911 issue

See also

edit- List of Vanity Fair artists

- List of Vanity Fair caricatures

- The Rowers of Vanity Fair Wikibook gives a history of the magazine with focus on sportsmen

References

edit- ^ a b "Vanity Fair: The One-Click History". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Vanity Fair cartoons: drawings by various artists, 1869-1910". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ a b Matthews, Roy T.; Mellini, Peter (1982). In 'Vanity Fair'. University of California Press. p. 17. ISBN 9780520043008.

- ^ a b "The legacy of Vanity Fair's caricatures". The Critic. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Spiring, Paul R (2009). The World of Vanity Fair by Bertram Fletcher Robinson. London: MX Publishing. ISBN 978-1-904312-53-6.

- ^ Deanna Haunsperger, Stephen Kennedy (31 July 2006). The Edge of the Universe: Celebrating Ten Years of Math Horizons. Mathematical Association of America. p. 22. ISBN 0-88385-555-0.

- ^ "Literary Gossip". The Week: A Canadian Journal of Politics, Literature, Science and Arts. 1 (18): 286. 3 April 1884. Retrieved 30 April 2013.