This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2015) |

Parinaud's syndrome is a constellation of neurological signs indicating injury to the dorsal midbrain. More specifically, compression of the vertical gaze center at the rostral interstitial nucleus of medial longitudinal fasciculus (riMLF).

| Parinaud's syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dorsal midbrain syndrome, vertical gaze palsy, upward gaze palzy, sunset sign,[1] setting-sun sign,[2] sun-setting sign,[3] sunsetting sign,[4] sunset eye sign,[5] setting-sun phenomenon[5] |

| |

| Specialty | Neurology |

It is a group of abnormalities of eye movement and pupil dysfunction and is named for Henri Parinaud[6][7] (1844–1905), considered to be the father of French ophthalmology.

Signs and symptoms

editParinaud's syndrome is a cluster of abnormalities of eye movement and pupil dysfunction, characterized by:

- Paralysis of upwards gaze: Downward gaze is usually preserved. This vertical palsy is supranuclear, so doll's head maneuver should elevate the eyes, but eventually all upward gaze mechanisms fail. In the extreme form, conjugate down gaze in the primary position, or the "setting-sun sign" is observed. Neurosurgeons see this sign most commonly in patients with hydrocephalus. [8]

- Pseudo-Argyll Robertson pupils: Accommodative paresis ensues, and pupils become mid-dilated and show light-near dissociation.

- Convergence-retraction nystagmus: Attempts at upward gaze often produce this phenomenon. On fast up-gaze, the eyes pull in and the globes retract. The easiest way to bring out this reaction is to ask the patient to follow down-going stripes on an optokinetic drum.[9]

- Eyelid retraction (Collier's sign)

It is also commonly associated with bilateral papilledema. It has less commonly been associated with spasm of accommodation on attempted upward gaze, pseudoabducens palsy (also known as thalamic esotropia) or slower movements of the abducting eye than the adducting eye during horizontal saccades, see-saw nystagmus and associated ocular motility deficits including skew deviation, oculomotor nerve palsy, trochlear nerve palsy and internuclear ophthalmoplegia.

Causes

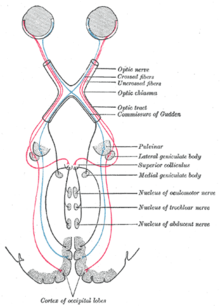

editParinaud's syndrome results from injury, either direct or compressive, to the dorsal midbrain. Specifically, compression or ischemic damage of the mesencephalic tectum, including the superior colliculus adjacent oculomotor (origin of cranial nerve III) and Edinger-Westphal nuclei, causing dysfunction to the motor function of the eye.

Classically, it has been associated with three major groups:

- Young patients with brain tumors in the pineal gland or midbrain, causing hydrocephalus

- Women in their 20s-30s with multiple sclerosis

- Older patients following stroke of the upper brainstem

However, any other compression, ischemia or damage to this region can produce these phenomena: hydrocephalus, midbrain hemorrhage, cerebral arteriovenous malformation, trauma and brainstem toxoplasmosis infection. Neoplasms and giant aneurysms of the posterior fossa have also been associated with the midbrain syndrome.

Vertical supranuclear ophthalmoplegia has also been associated with metabolic disorders, such as Niemann-Pick disease, Wilson's disease, kernicterus, and barbiturate overdose.

Diagnosis

editDiagnosis can be made via combination of physical exam, particularly deficits of the relevant cranial nerves. Confirmation can be made via imaging, such as CT scan or MRI.

Treatment

editTreatment is primarily directed towards etiology of the dorsal midbrain syndrome. A thorough workup, including neuroimaging is essential to rule out anatomic lesions or other causes of this syndrome. Visually significant upgaze palsy can be relieved with bilateral inferior rectus recessions. Retraction nystagmus and convergence movement are usually improved with this procedure as well.

Prognosis

editThe eye findings of Parinaud's syndrome generally improve slowly over months, especially with resolution of the causative factor; continued resolution after the first 3–6 months of onset is uncommon. However, rapid resolution after normalization of intracranial pressure following placement of a ventriculoperitoneal shunt has been reported.

References

edit- ^ Larner, A. J. (2001). A Dictionary of Neurological Signs: Clinical Neurosemiology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-4020-0042-3.

- ^ Biglan, Albert W. (January 1984). "Setting Sun Sign in Infants". American Orthoptic Journal. 34 (1): 114–116. doi:10.1080/0065955X.1984.11981637.

- ^ MPH, Eudocia Quant Lee, MD; MD, David Schiff; MD, Patrick Y. Wen (2011-09-28). Neurologic Complications of Cancer Therapy. Demos Medical Publishing. p. 383. ISBN 978-1-61705-019-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Waterston, Tony; Helms, Peter; Ward-Platt, Martin (2016-07-06). Paediatrics: A Core Text on Child Health, Second Edition. CRC Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-138-03131-9.

- ^ a b Gaillard, Frank. "Sunset eye sign | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- ^ synd/1906 at Who Named It?

- ^ H. Parinaud. Paralysie des mouvements associés des yeux. Archives de neurologie, Paris, 1883, 5: 145-172.

- ^ Neuro-Ophthalmic Examination

- ^ "Convergence-retraction nystagmus". www.aao.org. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

Further reading

edit- Aguilar-Rebolledo F, Zárate-Moysén A, Quintana-Roldán G (1998). "Parinaud's syndrome in children". Rev. Invest. Clin. (in Spanish). 50 (3): 217–20. PMID 9763886.

- Waga S, Okada M, Yamamoto Y (1979). "Reversibility of Parinaud syndrome in thalamic hemorrhage". Neurology. 29 (3): 407–9. doi:10.1212/wnl.29.3.407. PMID 571990. S2CID 42247406.